5 Comment: Is The Birth of a Nation a Western?

Alex Lichtenstein

Let me begin with a story, provoked by Peter Davis’s remarks about the interplay of Griffith’s vision and that of white South African filmmakers. Today, if you travel through KwaZulu-Natal Province in South Africa, you can visit a historic site where the Battle of Blood River (known by the Zulu as iMpi yaseNcome) occurred on December 16, 1838. This isolated spot is located twenty kilometers down a dirt road in an impoverished—though stunningly beautiful—rural area. In fact, there are two adjacent historic sites here, narrowly separated by the Ncome River though widely separated in conceptualization and intention. One, established in 1999 by the ruling African National Congress’s Department of Arts, Culture, Science and Technology, uses an elaborate museum display to recount the battle story from the point of view of African nationalism and, more particularly, Zulu nationalism. On the other side of the river, one finds a privately run older installation, the Bloedrivier Heritage Site, managed by the Stigting vir die Bloedrivier-Gelofteterrein (Foundation for the Site of the Blood River Vow).[1] On this latter site—first established in 1938 on the centenary of the battle—there sits a replica (built in 1971), of a round laager of wagons used by Boer pioneers (known as Voortrekkers) as a defensive rampart (fig. 5.1). In 1838, the story goes, the Voortrekkers had put their wagons in an interlocked circle to defend themselves against thousands of attacking Zulu warriors. This, of course, is the central event of Afrikaner nationalist mythology, dating right up to today.[2]

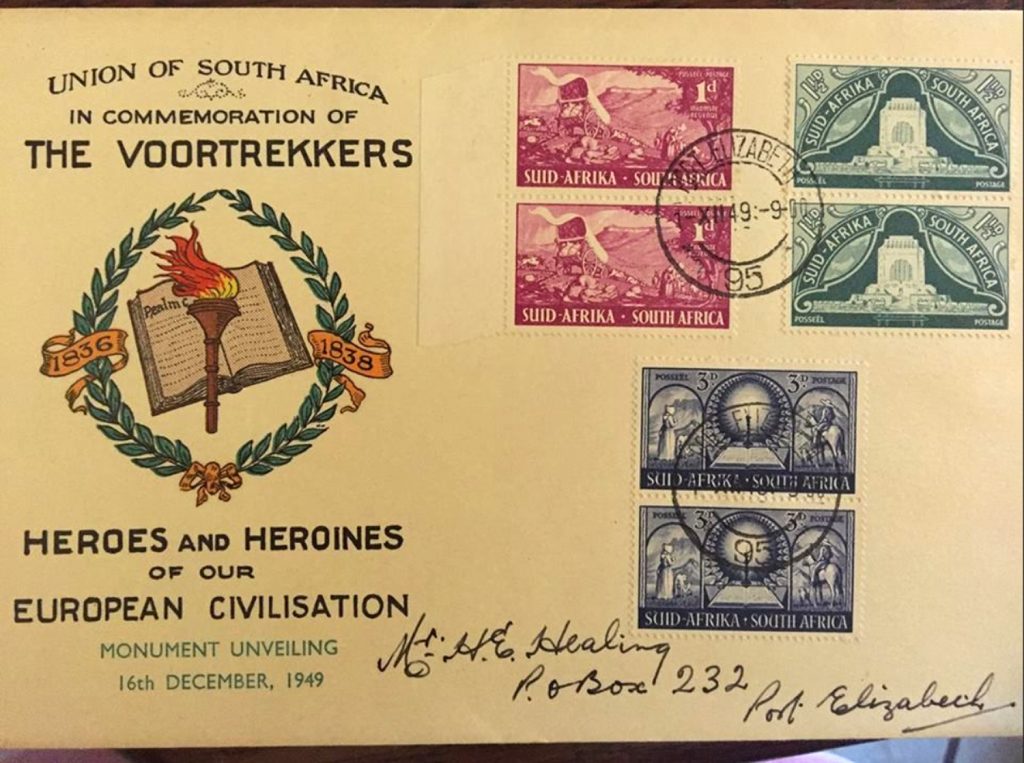

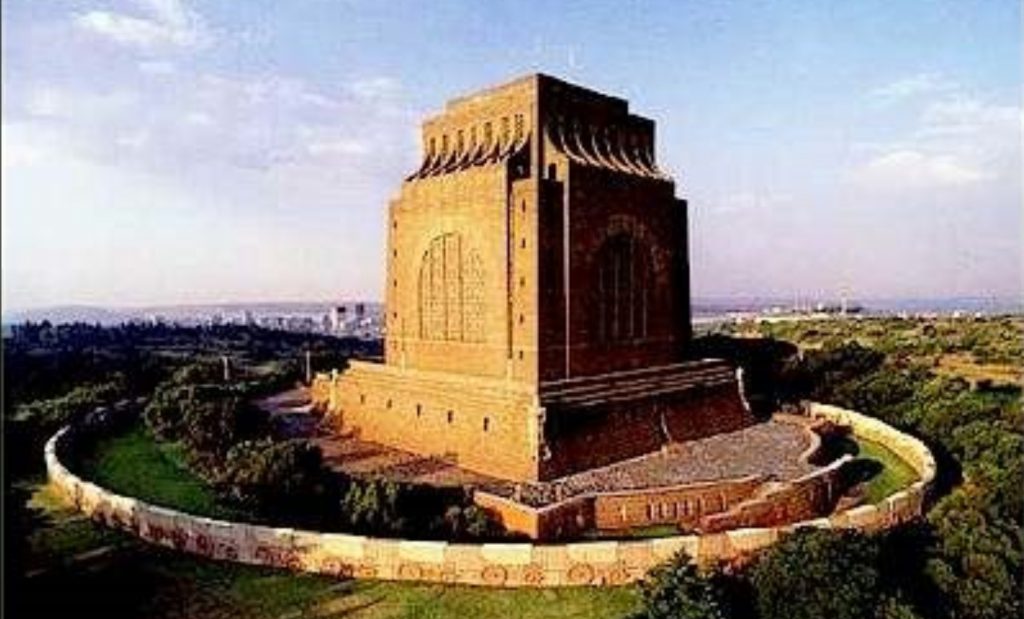

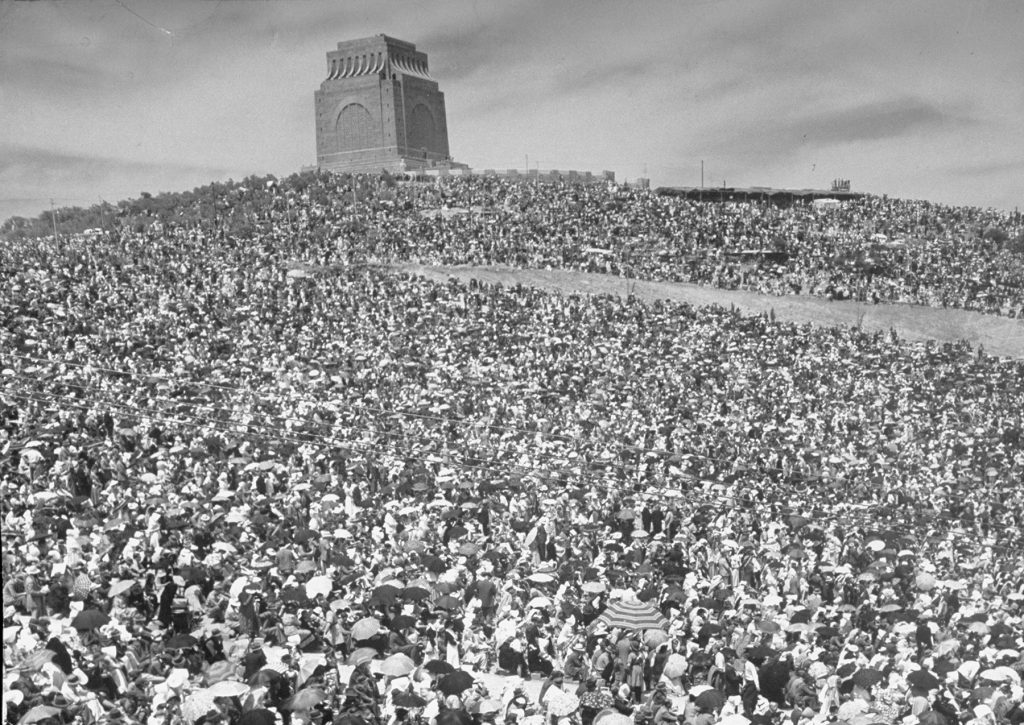

This incident, however, took on powerful significance in December 1938, when the centenary of the battle was celebrated by Afrikaners with a recreation of their Great Trek from the Western Cape into Natal and the Transvaal, where they had first directly encountered African peoples. Indeed, as Peter Davis notes, this commemoration proved the occasion for the 1938 release of a South African film, Die Bou van ‘N Nasie (They Built a Nation).[3] That same year, the reenacted Great Trek culminated with the laying of a cornerstone of the Voortrekker Monument on a hill above South Africa’s capital, Pretoria. On December 16, 1949, shortly after the electoral triumph of the Afrikaner nationalists, this monument was inaugurated with enormous fanfare, captured by, among others, Margaret Bourke-White for the pages of Life magazine (figs. 5.2a, 5.2b, and 5.2c).[4]

Visitors to the Bloedrivier Heritage Site today will find a small gift shop, run by a very pleasant Afrikaner family. If you ask, they will show you a forty-five-minute documentary film about the history of the Battle of Blood River. This film, it must be said, is narrated rather unapologetically from the Afrikaner point of view. The brave Voortrekkers are described as seeking to be “free from the stifling oppression and regulations of British rule,” with no mention of the British Empire’s abolition of slavery, to which they objected. Their antagonist, the “treacherous” Zulu king, Dingaan, murders the “unsuspecting” advance Voortrekker party led by Piet Retief (fig. 5.3).

Even the normally naïve British missionary, the film implies, chooses to flee Natal in the face of the stirred-up Zulu. What the Zulu warriors take to be wails of fear coming from within the circled wagons (the laager) of their enemies, the narrator assures, were instead the Voortrekkers bravely singing Christian hymns the night before the attack. The narration even gives some credence to the idea that the fortuitous natural defenses afforded by the laager’s position in the valley may, in fact, have been divinely ordained. In more earthly terms, this historical propaganda film relies on three elements: standard documentary voice-over illustrated with photographs, documents, paintings, and battle maps; contemporary dramatic landscape shots of the recreated laager (at dawn, at night, in the fog) set to swelling music; and, most interestingly for our purposes, many intercut historical film clips (described in the credits as rolprentinsetsels, or “archive films”). The clips are from the 1938 government-produced film They Built a Nation, a second South African dramatization of the Great Trek made in 1973 called Die Voortrekkers, and the 1986 South African Broadcasting Corporation television series Shaka Zulu (but not, oddly enough, from Harold Shaw’s 1916 silent film De Voortrekkers).[5] The 1938 film, in particular, is drawn on heavily to dramatize key moments in Afrikaner history, such as the murder of Retief and the Afrikaner covenant sealed on the so-called Day of the Vow, and, of course, the battle itself, marked by the heroic and miraculous defense of the laager surrounded by Zulu warriors (figs. 5.4, 5.5a, and 5.5b).

The Rand Daily Mail applauded the fact that in the film, “both English and Dutch are depicted as willing and eager to cooperate”—a marked contrast to subsequent uses of the film in the service of Afrikaner nationalist propaganda. The similarity to Griffith’s emphasis on a potential rapprochement of North and South at the expense of African Americans, then, is striking.[6] Given how the rolprentinsetsels footage is used in the Bloedrivier Heritage Site film, unsuspecting young viewers might be forgiven for imagining that this is actual footage of the event. Here, then, is a wonderful example of the repurposing of older films, in today’s postapartheid South Africa, to memorialize and recreate through a kind of bricolage the Afrikaner nationalist mythology that retains its hold on a small minority of the population. The protean character of these films as cultural artifacts perfectly illustrates how the white nationalist mythology embodied in both The Birth of a Nation and They Built a Nation does not disappear. Instead, it is constantly repurposed, reenacted, and recreated. Both of these white nationalist films remain profoundly unstable as icons, despite our desire to think of them in stable terms.

A second, more provocative, point I want to make is to question the tendency to view these two films as mere documents of racism, and little else. They certainly are shot through with racist ideology, and thus are easily deployed in revanchist historical narratives; but as films, their narratives were fundamentally nationalist in character rather than just racialist. Because they were produced in the name of rebuilding white solidarity, we should interrogate them as products of certain kinds of nationalism and nationalist moments. Now, certainly, that nationalism needs to be understood as a racial nationalism. As Marilyn Lake and Henry Reynolds suggest in their fine work Drawing the Global Colour Line, The Birth of a Nation burst upon the cultural scene at the very moment when the global color line was being drawn in Australia, South Africa, and the United States, as all of these settler societies felt a strong need to reassert white nationalism in the face of the international “rising tide of color.”[7] Yet such nationalism might be polyvalent. As Davis subtly suggests, in the South African case, in films such as De Voortrekkers (1916) and They Built a Nation, we need to consider how white nationalism operated on two planes. It was simultaneously white nationalism in the language of reconciliation between British and Boer after the South African War, and of Afrikaner nationalism in and of itself. That duality, of course, can also be applied to Griffith’s film, which expressed both the triumphant pseudonationalism of the white South through the defeat of Reconstruction and yet was also very much about sectional reconciliation. Surely, this remains its fundamental contribution to a nationalist mythology in the United States, burying the hatchet to reunify divided North and South once and for all by denigrating Reconstruction, its traitorous white enablers, and, most of all, its black beneficiaries and agents.

If these films both draw on narratives of renewed white supremacy and national reconciliation, we can simultaneously read The Birth of a Nation as a spectacular war film, shot through with battle scenes, not least because one could easily apply the same analysis to They Built a Nation. Certainly the latter is used that way by the sponsors of heritage at Bloedrivier, who cannibalize its battle scenes with abandon. A similar collection and recycling—dare I say curation—of images drawn from The Birth of a Nation as a war film seems to have occurred at crucial historical junctures within the United States. The film in its entirety may have been retrofitted as a nationalist trope, or as a “canonized history of film art,” but, as Andy Uhrich suggests in his essay in this volume, the manner in which collectors clipped up, repackaged, and resold The Birth of a Nation proved significant as well. In 1942, it was Griffith’s battle scenes that seemed most worthy of reanimation. That was a moment when everyone on the US home front was sitting in a movie theater watching battle scenes of what was happening in Europe or in the Pacific, in the name of promoting national unity against “slavery,” as the world of the Axis powers was termed in Frank Capra’s World War II film series Why We Fight. American moviegoers were accustomed, in 1942, to cinematic battle sequences filled with scenes of spectacularization. In 1953, of course, valorization of Griffith’s film took on—or reclaimed—a different, more sinister meaning, as it came to represent a means disguising a certain racial-nationalist narrative in the guise of film heritage. This, of course, occurred on the eve of the moment when the Confederate battle flag reappeared over Southern state capitals, the “Third Klan” began to ride against civil rights workers, and many white Southerners sought to fend off what they saw as the threat of a second Reconstruction.[8]

Yet we need to be cautious, and not condescend to the past. It is easy enough in our enlightened and allegedly postracial era to wonder how people watching at the time could possibly have missed the obvious racism of Griffith’s vision. But we should recall that in 1953, Griffith’s interpretation of Reconstruction that The Birth of a Nation had culturally crystallized for the nation in 1915, remained the dominant, mainstream understanding in North and South alike. As historian of Civil War memory David Blight notes, “by using powerful imagery . . . [The Birth of a Nation] etched a story of Reconstruction that has lasted long in America’s historical consciousness.” And although the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People protested the film in 1915, Griffith’s view of Reconstruction would have hardly been at odds with the view promulgated by Booker T. Washington at the time, notwithstanding his own occasional objections to the film (although, as Blight points out, “Washington supported Griffith’s right to show the film”).[9] In Up from Slavery (1901), Washington had declared that during Reconstruction, “the ignorance of my race was being used as a tool with which to help white men into office, and that there was an element in the North which wanted to punish the Southern white men by forcing the Negro into positions over the heads of the Southern whites.” A better synopsis of the historical narrative dramatized in Griffith’s film is hard to find. Four decades later, it didn’t take a stretch of imagination in either region for white audiences to agree that it was the carpetbaggers and the incompetent black voters they had manipulated that had made Reconstruction a terrible mistake. Griffith effectively played to white Americans’ preconceptions, which historians in the decades between 1915 and the rebirth of the civil rights movement during the 1950s had done very little to challenge or displace. With the major exception of W. E. B. Du Bois’s 1935 classic (though largely ignored) work Black Reconstruction, it was only in the wake of the civil rights movement and the historiographic revolutions that accompanied it that American historians rewrote the popular understanding of Reconstruction—which it seems even Hillary Clinton still clings to.[10]

A narrative of racial nationalism; a sign of reconciliation; a war film; a collection of ready-to-hand images attractive to those rummaging in the attic of heritage to defend or reclaim a lost world of white pride—when placed side by side, The Birth of a Nation and They Built a Nation conjure these political imaginaries. Yet we can also rethink their place within a different film narrative convention that is peculiar to both nations, even if in quite distinctive ways. There is a long, if now neglected, tradition of comparative US and South African history that takes the “frontier” as its basic analytical template. In both cases, despite many differences, for example, although both Native Americans and Africans welcomed European visitors at first, “it was not long before it dawned on the indigenes that they were up against a completely new type of person whose impact was more fundamentally devastating than anything they had previously experienced,” write Howard Lamar and Leonard Thompson.[11] Over the past several decades, however, a historiography more oriented to twentieth-century developments in both countries—including capitalist development, national integration, and modern black nationalism—has swept aside that earlier framework. Returning to these films as sources, however, reminds us that the modern white racist imagination at least remained imprinted with moving images that posed the taming of “savagery” by the spread of white “civilization” as central to defining national mythologies about frontier expansion. In the South African case, these two processes occurred in tandem, as the Voortrekkers’ wagon trains penetrating the interior of southern Africa entailed the eventual destruction of diverse indigenous societies that, in twentieth-century South Africa, became collectively subordinated as black to the white nationalist project. In the United States, the crushing of Native American resistance to the spread of whiteness and the perpetuation of white supremacy rooted in African American slavery and then the reassertion of post–Civil War Jim Crow are understood as distinctive (if perhaps related) processes, in both time and, especially, geography. They tend to draw on different tropes (the wagon train and the noble savage, the genteel plantation and the “happy negro,” for example), and we have become accustomed to experiencing these narratives visually within distinctive genres of film. Yet when we place Griffith’s work in dialogue with South Africa, we can discover some peculiar affinities.

This is especially the case if we return to the film that effectively bridges South African and American frontier narratives, Griffith’s 1908 short The Zulu’s Heart.[12] We often ask the wrong questions when we try to compare South African “race” films with The Birth of a Nation; we might even be asking the wrong genre question when we look at The Birth of a Nation as a war film, as interesting as that exercise may be. Consider Griffith’s “masterpiece” for a moment through the lens of a different transcultural narrative convention, the Western. The Zulu’s Heart, shot in New Jersey, allegedly set in nineteenth-century Natal to dramatize the encounter of a (lone) Voortrekker family with a Zulu chief, unquestionably was a Western, not a coherent or realistic narrative about the experience of whites in southern Africa. When Griffith shot this film, seven years before the release of The Birth of a Nation, he was imagining (or inventing) the Western, the (just vanished) North American frontier, and Native Americans in the West as the Other, not African Americans in the South. Even while casting his narrative in the guise of innocent white settlers in conflict with indigenous Africans on the southern African frontier, Griffith was obviously drawing on American frontier captivity narratives. The Zulu king who gallantly rescues the Boer mother and child from his savage comrades should be understood as a stand-in for a Native American, not an African American “savage.” Similarly, when the American filmmaker Harold Shaw premiered his South African–made 1916 epic about the “birth” of that nation, De Voortrekkers, the Rand Daily Mail swooned over “the loyalty to the trekkers of a simple [Zulu] savage.”[13] So while we surely can regard The Birth of a Nation as a pure expression of white nationalism, or even as a spectacular war film, we might also consider it from this different angle. Indeed, I would argue that when the war film meets the racial nationalist film in a settler society—whether it be Australia, South Africa, or the United States—it comes clothed in the narrative conventions of the Western (fig. 5.6).

Alex Lichtenstein is Professor of History at Indiana University. He is author of Margaret Bourke-White and the Dawn of Apartheid.

- For an analysis of these competing heritage sites, see Nsizwa Dlamini, “The Battle of Ncome Project: State Memorialism, Discomforting Spaces,” Southern African Humanities 13 (December 2001):125–138; and Paula Girshick, “Ncome Museum/Monument: From Reconciliation to Resistance,” Museum Anthropology 27(1–2): 25–36. ↵

- Leonard P. Thompson, The Political Mythology of Apartheid (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1985), 144–184. ↵

- See Peter Davis, In Darkest Hollywood: Exploring the Jungles of Cinema’s South Africa (Johannesburg: Ravan Press, 1996), 147–149. The title They Built a Nation is the literal English translation of the film, but it is also common to see the film referred to as Building a Nation. ↵

- Alex Lichtenstein and Rick Halpern, Margaret Bourke-White and the Dawn of Apartheid (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2016). ↵

- On Shaka Zulu, see Davis, In Darkest Hollywood, 167–182. ↵

- Rand Daily Mail, December 20, 1938, 23; Nina Silber, “Reunion and Reconciliation, Reviewed and Reconsidered,” Journal of American History 103 (June 2016): 59–83. ↵

- Marilyn Lake and Henry Reynolds, Drawing the Global Colour Line: White Men’s Countries and the International Challenge of Racial Equality (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009); Lothrop Stoddard, The Rising Tide of Color against White World-Supremacy (New York: Scribner, 1920). ↵

- David Goldfield, Still Fighting the Civil War: The American South and Southern History (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2013), 311–312. ↵

- David Blight, Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001), 395–396. ↵

- Booker T. Washington, Up from Slavery: An Autobiography (New York: Doubleday, 1901), 84; W. E. B. Du Bois, Black Reconstruction: An Essay Toward a History of the Part Which Black Folk Played in America, 1860–1880 (New York: Russel & Russel, 1935). The most important “revisionist” account of Reconstruction is Eric Foner, Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863–1877 (New York: Harper & Row, 1988); Ta-Nehisi Coates, “Hillary Clinton Goes Back to the Dunning School,” The Atlantic (online), January 26, 2016. ↵

- Howard Lamar and Leonard Thompson, eds., The Frontier in History: North America and Southern Africa Compared (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1981), 18; George Frederickson, White Supremacy: A Comparative Study in American and South African History (New York: Oxford University Press, 1981), chap. 1. ↵

- Davis, In Darkest Hollywood, 8–9, 124–125. ↵

- Rand Daily Mail, December 27, 1916, 7. ↵