11 Race, Space, Sexuality, and Suffering in The Birth of a Nation and Get Hard

David C. Wall

As Anna Everett, in Returning the Gaze: A Genealogy of Black Film Criticism, makes clear, whatever may be said of D. W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation, its “secure place in the annals of American and international film histories” is assured.[1] But how do we continue to make sense of this film—one of the key canonical texts of world cinema—especially at this particular historical moment, one hundred years after its first release? Formed by the adjudicating processes of assessment and investment that are the product of history and ideology, cultural canons inevitably both reflect and refract broader cultural discourses; and The Birth of a Nation’s continued presence and importance in the field speaks to the ongoing cultural and ideological labor in which it is engaged. In considering why it still matters, and the ways that we make sense of it as we try to describe, understand, and interpret, we need to think also of how its own sense-making structures work in relation to the multiple domains in which the film is situated. In other words, we must consider how it means as much as what it means.

Mainstream film studies and criticism—historically and institutionally white, of course—have routinely downplayed The Birth of a Nation’s overt and ugly racism in the promotion of its formal technique and artistic quality. This lenticular approach to the film suggests that its content and form are entirely separable elements of the cinematic experience and that we can simply choose to isolate one or the other. But, of course, this is a chimera. It is the effervescent dynamism of The Birth of a Nation’s structural qualities that so convincingly articulates the film’s racial consciousness. The routine relegation of racial representation as a mere adjunct to the film’s form is perhaps a paradigmatic example of the way in which the ideological structures of film studies as an academic discipline still attempt to coerce the viewer-critic into a presumptive sympathy with a white subject. However, notwithstanding the enormous amount of writing on The Birth of a Nation that lays claim to what, in a different context Benedict Anderson referred to as a “halo of disinterestedness,”[2] it is clear that, as James Snead puts it, in D. W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation, “film form and racism coalesce into myth.”[3] The film’s formal elements are not separable from its political and ideological assertions. In short, its aesthetic is its racism.

We should keep in mind that this text is a living thing—not merely an artifact of the past but something constantly at work in the present, still laboring to assert its discursive and ideological claims, sitting as it does in constant conversation with much more recent texts. To quote Snead again, the mythifications of race are “political in nature . . . [and] continue to assert their presence today.”[4] So we, as contemporary spectators, cannot, in any meaningful sense, remove ourselves from the history of this film or those subject positions we occupy that inform and inevitably shape our responses to it any more than we can remove ourselves from the multitude of discursive networks of history, race, and visuality that we (and the film) inhabit.

The Birth of a Nation’s relationship to history is especially fascinating and complicated. The film makes a constant and committed effort to offer itself up as factual history as well as dramatic enactment and epic entertainment. In its strategic deployment of character, narrative, and plot, the film labors to provide a collective memory for its white audience rooted not in nationality or region but in race. Considering the contingent histories of its multiple (and constantly multiplying) contexts, we can think of The Birth of a Nation’s relationship to history in three distinct and inextricably related ways: first, the film claims to “document” the past as it purports to depict a history of things, events, people, and places as they actually were in the past; second, it is itself a document of history in that it is the product of the historical and cultural moment from which it emerges; and, third, it sees itself as an engine of history in that it has a clearly articulated political function.[5]

Considering how important history is, then, to Griffith’s project, the apolitical approach of removing the aesthetic from the ideological is an even more remarkable strategy. Its presence and power in the service of whiteness has not emerged over time; this is no revisionist assessment but rather is present from its very inception. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People’s protests against the film along with an attendant “intense furor” resulting in “censorship, demonstrations, and race riots,”[6] were a corollary to the resurgence in interest and membership of the Ku Klux Klan that emerged in the wake of the film’s release. As well as clearly indicating, as Ed Guerrero puts it, “how deadly serious the new medium, barely twenty years old, had become as a tool to create and shape public opinion and racial perceptions,”[7] that controversy reveals just how conscious the contemporary audience was of the absolute centrality of race to the film’s significance.

Guerrero’s emphasizing of the medium’s newness is also critically important as cinema becomes a collision point for race and modernity. This new and dynamic technology of seeing and being constitutes perhaps the crucial arena of visuality to which black America both has access and is made subject/object of. In short, there is no cinematic technique, there is no aesthetic, there is no film without its racial representations. Without its black bodies, The Birth of a Nation does not exist. The extracinematic codes, then, that Snead’s Barthesian reading of The Birth of a Nation argues both structure and support the construction of the racial subject in the film might be just as usefully considered as critical elements in the network of what Ella Shohat and Robert Stam refer to as that wider “orchestration of ideological discourses”[8] that constitute culture through the scopic regimes of race and space. And what we see codified in The Birth of a Nation we see reiterated repeatedly throughout the history of American cinema.

In choosing to read Get Hard (dir. Etan Cohen, 2015) in relation to The Birth of a Nation, I assert that those same scopic regimes remain in play in contemporary American film. Indeed, part of the purpose of the centennial symposium, “From Cinematic Past to Fast Forward Present: D. W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation,” held at Indiana University in 2015 and from which this volume is derived, was to demonstrate the profound and continued presence of Griffith’s film across the landscape of American culture. It takes little effort to identify myriad films that, whether consciously or not, draw on the racial representations that coalesced in Griffith’s epic. From Judge Priest (dir. John Ford, 1934) to Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner (dir. Stanley Kramer, 1967) to Django Unchained (dir. Quentin Tarantino, 2012), American film unavoidably speaks race through the visual grammars of blackness cemented by The Birth of a Nation. In this respect, Get Hard is an especially interesting correlative text. Its release exactly one hundred years after The Birth of a Nation offers a neat historical confluence, but a greater significance resides in the film’s central assertion that blacks are both the cause of (and corrective to) white suffering, along with a concurrent deployment of blackface as the central narrative conceit. Though Get Hard’s parsing of race is designed (I think) with the intention of playing with, and even subverting, those long-standing tropes and stereotypes, its failure in this task results in an inevitable retrenchment of racist imagery that, notwithstanding its intentions, proves no less pernicious than that in The Birth of a Nation.

My reading of these films is informed implicitly, if not explicitly, by Russian critic Mikhail Bakhtin’s concept of the dialogic. Bakhtin has generated a veritable industry of scholarship since his works were introduced to the West in the 1960s and 1970s. The breadth of his thinking and range of analysis is extraordinary, but, as Martin Flanagan points out, it is dialogism that “provides the closest thing there is to a dominant metaphor in the Bakhtinian oeuvre.”[9] In The Dialogic Imagination, an analysis of novelistic language in general and Dostoevsky in particular, Bakhtin asserts a fundamental argument that all meaning derives from dialogue—that is, the interaction between two actors or agents in history. Acknowledging that my description of Bakhtin’s analysis here is necessarily superficial, it is important to at least gesture toward the complexity of his thought in this arena. Dialogism goes beyond merely a sense-making process of conversation, so to speak, and reaches to the very depths of the structures of subjectivity. Seeing the subject rooted in language puts Bakhtin in the company, of course, of many other linguists and philosophers of the twentieth century. But he moves beyond merely seeing identity rooted in language to understanding it as dialogue itself and, thus, a product of otherness at its most fundamental level. As Michael Holquist puts it, “in dialogism consciousness is otherness.”[10] Further, “there is an intimate connection between the project of language and the project of selfhood: they both exist in order to mean.”[11]

Critical to the project of dialogism, then, is an acknowledgement that understanding/sense making is a process—a constantly renegotiated settlement of meaning—rather than a terminal point of arrival. Approaching film this way forces an acknowledgment that our own relationship to the text is an ongoing process of discursive engagement rather than simply the passive consumption of product or the critical assessment of an object entirely external to ourselves. Our relationship to, and membership in, the discourse communities that surround the production, dissemination, and consumption of The Birth of a Nation and Get Hard mean that we play a crucial role in the constant recreation and redefinition of the text, just as it plays a role in ideologically making claims on us. The plethora of events, symposia, and conferences addressing the centenary of The Birth of a Nation’s release stands as compelling evidence for this.

Just as characters work dialogically within the frame of the film, viewers are also structured by their dialogic relationships to the events and utterances—in the broadest sense of that term—that they experience on the screen (as well as all that they experience beyond it.) As individual characters in the films are socially and cinematically constituted subjects, viewers are also socially and cinematically constituted subjects. So, while we as subjects are, of course, present and conscious in reality—in Bakhtin’s own oft-repeated assertion, “there is no alibi for being”—at the same time, our subjectivity and selfhood are products of the roiling polyphonic discourses into which we are interpolated and through which we are individuated. Alterity—the inevitable, unavoidable, and constant dialogic presence of the other—is fundamentally constitutive of that self. While the febrile dynamics of alterity can help make sense of the ways in which the cinematic text plays a crucial role in the construction of the subject in a general sense, it seems peculiarly appropriate as a framework for reading The Birth of a Nation, which is already so overtly and profoundly structured on disgust toward and desire for a racial Other. However, while accepting that we make meaning of the text as much as we take meaning from the text, finding ourselves on ground that is always contestable and indeed always contested, no film is simply an inchoate or empty eruption waiting for us to pour meaning into it. Indeed, every text asserts a claim to an “official” reading, even though that claim is always doomed to failure.

I will turn to a discussion of Get Hard shortly, but first I want to consider The Birth of a Nation in terms of what Cedric Robinson refers to as its “neurotic sexuality,”[12] for it is The Birth of a Nation’s articulation of racial anxiety through that neurotic sexuality that most profoundly links it to Get Hard. There is not one moment in The Birth of a Nation when the residue and trace of white desire for the black body is not present, ghostwritten through every frame. It may have been the case that, as Robert Lang suggests, Griffith made the film in large part as a propaganda effort against miscegenation,[13] but as Martin Flanagan points out, “texts are perhaps at their most energetically meaningful when their contradictions are exposed.”[14]

Notwithstanding the film’s apparent desperate aversion to the idea of racial mixing, it gives itself up to a phobic fascination with the very thing it purports to disdain. A couple of well-known examples are instructive here. Consider the visual grammar of the infamous sequence in which Flora Cameron is pursued to her death by Gus, stroked as it is with an erotic charge derived from the excitement of the chase. Consider, too, the equally famous scene toward the end of the film with the “little party in the besieged cabin” as the film returns again and again to the threatened white female body and the tantalizing teasing possibilities of sexual violation and transgression. Fear and fascination here are always intertwined as what is socially marginal always becomes symbolically central. As Peter Stallybrass and Allon White put it, “disgust always bears the imprint of desire.”[15] So, as the film consistently stakes its claim for the inviolable and fundamental purity of whiteness, it betrays an equally insistent fascination with a racial messiness that abjures purity, with an abjection pervading the margins where the racial system teeters constantly on the brink of collapse. The carefully demarcated spaces of whiteness—the cabin, the street, the Camerons’ house, Flora’s innocent body—are continually ruptured, and the boundaries repeatedly transgressed. In the process, these spaces become “privileged sites of male exchange, racial violence, erotic investment, and spectatorial interest.”[16]

I would argue that one of the reasons for The Birth of a Nation’s success and endurance is that it extends to the deepest recesses of white subjectivity—not only in how it represents and portrays blackness on the screen but in its profound dialogical reliance on the structures of white desire for the black body. As Robert Lang notes, “the film’s obsession with miscegenation is the key to its structure and meaning as melodrama.”[17] And further, as Susan Courtenay argues, it is the compelling and irresistible fantasy of the “conjured threat of the black rapist” on which the film’s entire “purifying project” is founded.[18]

This irresistible fantasy, though articulated in less explicit or overt ways, is no less consistent in much more recent American film. From The Last King of Scotland (dir. Kevin Macdonald, 2006) to Cop Out (dir. Kevin Smith, 2010) to Django Unchained, the same fascination with the black body that is so redolent of The Birth of a Nation adumbrates mainstream representations of race. The broad landscape of twenty-first-century Hollywood images of blackness functions as a reworked canvas for the “purifying project” to which Courtenay refers. And those same scopic registers that are at work in The Birth of a Nation continue their visual and cultural labor in Get Hard as the spatial and racial boundaries between white and black, rich and poor, free and imprisoned, gay and straight, are tantalizingly and continually collapsed and reconstituted. The implied gaze at this complicated and compelling spectacle of race, romance, disgust, and desire is perforce white, heterosexual, and male.

In addressing what she terms the “birth of the ‘great white’ spectator,” Courtenay situates a fascinating link between The Birth of a Nation and early twentieth-century newsreel films of the great black heavyweight boxer Jack Johnson. The contradictory impulses of fear and fascination that the Johnson footage elicited in its white audiences speaks to a fundamentally voyeuristic relationship to blackness that of course existed prior to the emergence of film.[19] (Indeed, we might argue that the entire history of white visual representations of the black body is predicated on that desirous impulse to voyeurism.) Eastman Johnson’s famous Negro Life at the South (1859) is only one emblematic—albeit especially telling—example in its mapping of the visual tropes and encodings that shape race as a profoundly scopic experience, validating the “white gaze” as it does.[20] But we also should consider the limitless range of advertisements, cartoons, blackface performance, antislavery propaganda, board games, book and magazine covers, and on and on and on. Every image is stroked with desire for the black body, placed ubiquitously as the visual property of the white gaze. Whether in abjection, subjection, trauma, service, or even death, the image of the black body is always and everywhere available for the enjoyment of the white spectator.

Even though the roiling ambivalence of disgust and desire that is the constant companion of these images was nothing new, the exciting technology of cinema allowed for these visual discourses to be constituted and disseminated in wholly new and modern ways. And as well as widening the arena for the subjection of the black body for a white audience, Courtenay argues that both the Jack Johnson newsreel films and The Birth of a Nation performed a critical function in serving up powerful cinematic “inscriptions” of “white suffering” and “agony.” Further, “the image of a black man beating a white man has everything to do with the production of the image of a black man desiring a white woman.”[21] White masculinity, then, is predicated on a nexus of anxiety where race, sex, violence, and desire collide.

Further, the profound linkages between the white spectator, the black body, and the act of violence serve as a network through which the fear of black sexual violence becomes reconstituted as a site of desire for that black body. At this moment of “profound representational struggle in American cinema,”[22] the white spectator is never merely watching a black image on the cinema screen but is being constantly dialogically constructed and individuated by that image. And white suffering is a critical element of that desire, as a node of discursive instability, in which the white subject may play with the compelling possibilities of that which it finds equally fearful and fascinating. From blackface through popular white appropriation of cultural and musical styles and language, those performative possibilities imply a dizzying set of complicated and contradictory narratives of resistance, rejection, and even liberation.[23]

As the landscape of visual culture is structured in relation to all other cultural and social domains, spatial nodes are critical to understanding the construction of the black body as a visual object. Built into the very possibilities that those bodies might represent is their spatial, as well as racial, circumscription; as the body is defined by those spaces to which it is granted or refused access, space is always and inevitably racialized. The boundaries of the cinema frame contain the black body just as it is contained within the carefully demarcated spaces of the cotton field, the big house, the slave quarters, or the ghetto. Part of the anxiety implicit in the scene in which Gus chases Flora Cameron—and which Griffith’s celebrated cinematic technique creates—is the black body roaming, out of control, through space previously controlled by an ever-present—even if sometimes only implied—whiteness. The black body roaming free is an uncontrolled body, and the uncontrolled black body is deeply threatening. And so space itself allows for the scopic regimes of cinematic spectatorship as well as functioning as the literal and metaphorical center of a visual racial registry where fear, violence, and desire collide.

A brief sequence early in The Birth of a Nation demonstrates how even the most apparently innocent image is striated with this desire. The Northern Stoneman family are visiting their Cameron cousins in the South. As the Stonemans are shown around the Camerons’ estate, an increasing affection develops between Phil Stoneman and Margaret Cameron. “Over the plantation to the cotton fields,” the intertitles tell us, “By way of Love Valley,” we follow the young lovers as Griffith employs several cinematic techniques to draw viewers in to the burgeoning romance, not least a scene of pastoral, prelapsarian innocence as they stand together in the far distance of a picturesque landscape (fig. 11.1).

As we move through the frames of the film, we move through the development of this romance as the lovers walk on, all of which demands a discursive set of exchanges that are structured in terms of both race and space. The narrative of white romance—white desire—is given a rather odd charge by its acting out at the point of the laboring black body. As the lovers walk in long shot across Love Valley, the scene fades to a short documentary-like sequence of close-up and medium shots of slaves picking cotton. As Griffith lingers on those real black bodies working in the field, the white lovers enter the frame. With the whites now in medium shot, the background is filled with black slaves. In this brief sequence, Griffith structurally links white romantic desire to the black laboring body. The space of romance is simultaneously the space of racial violence and abjection, and the spatial relationship established between the white and black bodies in this sequence is a perfect visual embodiment of the broader social structures of race. Those white and black bodies are present simultaneously and yet entirely separated; the laboring black body is relegated to the rear of the scene as the carefree young white cousins wander throughout, always facing out toward us, standing with their backs to reality and, perhaps, to history. This sequence not only emphasizes that white desire is fundamentally predicated on the marginalized black body but also reinforces the spatial demarcations of race while showing the permeability of those boundaries.

This burgeoning romance occurs at the beginning of the film and thus serves as the foundation for the suturing of North and South through their shared foundational whiteness. It also asserts the essentially benign nature of white power. The spaces occupied by these happy and laboring black bodies is neat, controlled, and well ordered, precisely because they are being carefully husbanded by the gentle, guiding hand of white paternalism. But as the narrative progresses and the Reconstruction period begins, the film portrays the breakdown of the spatial order as a direct consequence of the breakdown of the racial order. From the notorious scene in the statehouse to the white residents of Piedmont being accosted in the streets by newly liberated blacks, from the infamous black Gus rape sequence to the besieging of the Camerons’ cabin toward the film’s end, the spatial ordering of blackness is defined by criminality and chaos.

This visual encoding of racial power as spatial power becomes a standard Hollywood trope from The Birth of a Nation to the present day, and Etan Cohen’s Get Hard is merely one of the latest iterations of Griffith’s spectacle of space and race. Considering Get Hard in dialogic relation to The Birth of a Nation, we can identify how the films mean in similar ways and draw them together through a consideration of the way space, race, and the black body are all utilized as critical elements in the experience of looking. Fundamentally, their shared structures of meaning are predicated on the establishment and maintenance of boundaries and markers—both literal and figurative—that allow for the constant renewal and relegitimation of the scopic regimes of whiteness so that space itself becomes the site at which, through which, and from which the film is asking us to understand it. As the white gaze is defined by a scopophilic obsession with the black body, we might expect those spaces to not only speak whiteness but also be eroticized in some way. Desire for the black body can be thought of, then, as a suturing element for a white gaze that links space and race. More than this, characterized by that same neurotic sexuality that Cecil Robinson identifies as pervading The Birth of a Nation, Get Hard utilizes space as critical to the construction and performance of race as it situates white suffering at its discursive and ideological center.

Starring Will Ferrell as multimillionaire financial wizard James King, framed for embezzlement and sentenced to ten years in federal prison, Get Hard opens with King’s white body in the agony of despair. Establishing the centrality of white suffering for the ensuing narrative, King fills the frame, weeping and wailing, his body in heaving spasms. Then the film flashes back to “one month ago”; an aerial long shot shows a Bel Air street sign as a black SUV enters the zone of privileged whiteness below. The camera then tracks through James King’s house, arriving ultimately in his bedroom via a montage of interiors that serve as banally predictable signifiers of wealth (expensive furniture, housekeepers, gardeners, a wine cellar) and slightly more subtly coded signifiers of whiteness. At the same time, the sound track plays Iggy Azalea’s “Fancy.” This jarring eruption of “blackness” into such a carefully controlled and contained white space gestures toward the oncoming and imminent collapse of cultural and racial boundaries on which the film’s narrative is predicated. But, of course, Iggy Azalea is not black. A white Australian performer who has adopted the language and style of contemporary African American rap, her presence points to the complexity of race as performance that adumbrates the film.

The configuring of race and space continues throughout the lengthy opening and credits sequence as a series of juxtapositions contrasts the material circumstances of the lives of the two main characters. Cuts of Bel Air and the unidentified “ghetto” shift from King’s mansion to a rundown city neighborhood street (with the predictable cop car driving slowly by) and then to the interior of the house of Darnell Lewis (Kevin Hart), where we see him on the phone discussing a mortgage problem. We then see Lewis’s daughter entering school through a metal detector as yet another cop drives by. This spatialization of race through stereotypical signifiers of blackness, criminality, and violence is linked to the legitimizing presence of white authority. The two domestic circumstances are also contrasted: King’s is wealthy, well ordered, clean, quiet, highly controlled, and sterile; Lewis’s is messy, chaotic, noisy, and yet warm and loving. The high/low dichotomy of their lives is perhaps best encapsulated by the sequence of split-screen images of the two men arriving simultaneously at the same workplace. In the upper half of the screen, James King strides into the building’s foyer and up the escalator. In the screen’s bottom half, Darnell Lewis drives his battered flatbed truck into the basement (fig. 11.2).

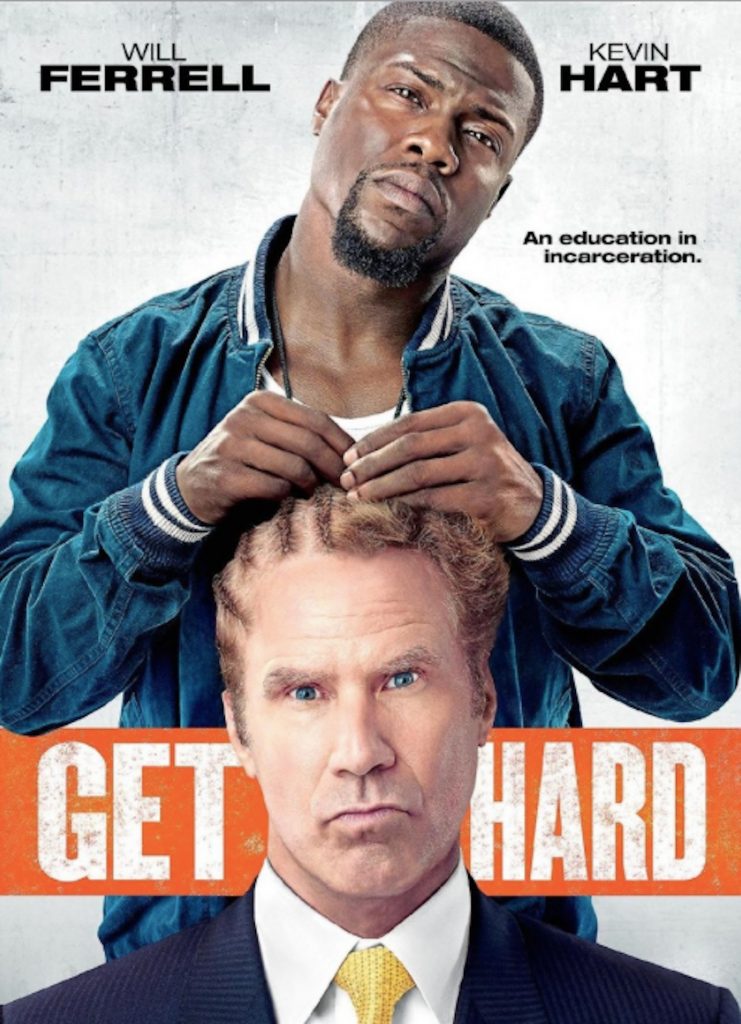

The first physical contact between the two characters comes when King goes to collect his car, which has been left with Lewis’s cleaning company (which operates out of the basement of King’s office building). There is some brief confusion when King assumes that Lewis is trying to mug him. With the confusion sorted out, King asserts that he would have reacted in exactly the same way had Lewis been white. This comic scene reveals the film’s effort to consciously engage with contemporary discourses around cultural representations of race. This effort is demonstrated even more clearly in the film’s theatrical poster (fig. 11.3). The image of Will Ferrell having his hair put into cornrows by Kevin Hart is a self-conscious and comic gesture toward the presence and power of visual stereotypes. Its visual charge comes from a comic inversion whereby a white middle-age businessman is sporting “black” hair. This series of significations can be read as a twenty-first-century movie winking knowingly at its audience as it lays claim to a sophisticated understanding of the workings of race as performance. But in other ways, the movie is merely the stage for a blackface performance in the grand tradition of minstrelsy.

During the early years of cinema, conventions of blackface performance were carried over from other arenas of entertainment. No less than in vaudeville or music halls, performers and audiences were never seduced into thinking they were seeing black performers. Indeed, the point for white spectators was that they were quite deliberately and purposefully enjoying whites performing their fantasies of blackness. Like other films of the period, The Birth of a Nation employs both white and black actors, but the principal black characters are always played by whites. In The Birth of a Nation, Gus (played by Walter Long) metonymically embodies the entire structure of white fascination with black sexuality as obsessive, repressed, and denied, and phobic in its return. To have a black actor in the role would demand an acknowledgment of that fascination. But a white actor allows for the portrayal to be shifted through a second-order representation so that blackness and black male sexuality become a dominant fetish for a white—especially male—gaze. Blackface in film allows a safe space for white fantasies of transgression and desire, because the overt and explicit nature of blackness as performance always allows for the arresting of the fantasy at a point of complete abandonment and the terror that whiteness may disappear forever. As that is true for Walter Long as Gus, it is true for Will Ferrell as James King.[24]

While the film’s knowing allusion to “blacking-up” asserts a consciousness of the operative discourses of race, it simultaneously—and perhaps much less self-consciously—articulates the freedom with which whiteness may choose to shift through the sets of visual significations and codifiers of blackness at will. In doing so, Get Hard employs the kind of complex and contradictory visual and narrative strategies seen in all interracial buddy films. The film’s racial awareness must be situated in, and lay claim to, the violence of history so that it may then be allowed the fantasy suturing of those racial antagonisms. In other words, for the gags about stereotyping to work, the narrative must acknowledge the realities of the racial discourses outside the frame. At the same time, the narrative wants to sit outside a history in which all mainstream Hollywood systems of representation are designed to please, tease, and titillate the white eye. The ambiguity surrounding the labor of these multivalent racial, ethnic, and cultural signifiers points to the complexity of demarcations that are both fluid and flexible.

The confrontation of the boundary is always a process of pleasure as well as policing. As the film’s narrative unfolds, we follow James King’s body as it is constantly being reconstituted at the boundary of black and white. And it is at those critical boundary points of rejection and reconstitution that King ultimately seeks and finds his redemption, for if it is anything, Get Hard is a film about salvation. And that salvation is realized through his performance of blackface.

In this moment, there is a fascinating further correspondence around blackface as a performative strategy to be made with The Birth of a Nation. In Griffith’s film, the faithful black servants, who offer a form of racial, political, and even transcendental salvation to the whites, are performing blackface in a number of complicated ways. Within the frame of the film, a certain performance of blackness is defined and demanded by the whites. Reliant for their own (literal and figurative) white existence on the black bodies surrounding them, the Stonemans and Camerons need blackness to be performed in very specific ways and along a spectrum from the “faithful souls” to the animalistic black Gus. But without the frame of the film, that same cultural labor, undertaken by both black and white actors, is being performed for the film’s white audience. Get Hard struggles with this complex process in its self-reflexive and self-conscious invocation of the problematics of blackface. Though making a sincere attempt at a kind of metarendering of race that would deplete blackface of its aggressive power, the film can never escape the form’s troubled history. In this sense, as a product of Hollywood, Get Hard cannot be seen as anything but in direct conversation with The Birth of a Nation and the broader history of racial representation in American cinema. And that history tells us, time and time again, that white bodies under threat are rescued by blacks. Moving beyond Griffith, however, there is a significant difference in that James King is redeemed not only by the presence and faithful service of Darnell Lewis but also by his own abjection and suffering as part of the process of his becoming black.

Knowing that he will be unable to cope with the ten-year stretch in prison that he is imminently to begin, King employs the services of Lewis to “teach” him how to survive in prison. But survival in this context really functions as a second-order metonymic signification. What King actually wants is Lewis to teach him how to be black, because it is through the codifications and discourses of blackness that King believes he will be able to avoid suffering and trauma. But there is a complicated paradox at work here. The suffering to which Lewis subjects King by way of toughening him up—getting him hard—for prison becomes a mode of resistance and redemption. But, of course, it is merely the playing out of suffering and trauma, the fantasy gesture of a white body choosing to subject itself to those disciplinary and carceral processes to which the real black body in history has been unwillingly and ubiquitously consigned.

The demeaning and debasing of the white body by a powerful black figure recalls that earlier fascination that was folded into both the spectatorial experience of watching the Jack Johnson newsreels and the sense of white victimhood that pervades The Birth of a Nation. As Darnell Lewis turns James King’s house into a prison, suffering is then spatialized with the tennis court now the “yard” and the wine cellar now the “cell.” This triangulation of race, space, and trauma struggles to elide the fundamental paradox at the heart of white fear of and fascination with black bodies. James King is terrified of being black, of being made subject to the demeaning, dehumanizing traumas and agonies of a black body; and yet he is simultaneously demanding that he be made subject to those very same processes of abuse and abjection.

Blackface as a central comic conceit is made explicit in the film, most notably when Lewis decides to take King to meet his gang-banging cousin Russell in the “hood.” Explaining that Russell is “very suspicious of outsiders. You walking in there they’re probably going to think you’re a cop off the bat,” the following telephone conversation takes place:

DL: “I need you to do something for me so that we don’t create any dangerous situations.”

JK: Blackface?

DL: What the fuck was that?!

JK: I’ll see you tomorrow. [he hangs up quickly]

DL: James! James! Don’t do nothing stupid. Just dress casual.

This exchange sets up the visual gag for the next scene, when, the next morning, Lewis arrives at King’s house to collect him. A close-up of Lewis’s incredulous face as King exits his house cuts to a brief sequence shot and edited like a music video. With Nicki Minaj’s “Beez in the Trap” playing on the sound track, King walks in slow motion toward Lewis’s car, his gardener and ground staff dancing in the background. Dressed, as he explains to Lewis, “like L’il Wayne,” King is, indeed, in blackface (fig. 11.4).

The blackface issue is raised again when the two men arrive at Russell’s house. With King sitting low to the floor surrounded by various members of the Crenshaw Kings, Russell sits opposite (in every sense) embodying a supposedly authentic black heteromasculinity. King explains: “I need protection and I’m hoping to join the Crenshaw Kings,” to which, through riotous laughter, Russell replies: “I’ve seen white people before but you motherfucker, man, you white as mayonnaise.” He laughs. “Oh shit, maybe in blackface, who knows?” Causing King to look subtly in admonishment at Lewis, Russell’s reference to blackface asserts again the film’s self-conscious employment of race as a cultural signifier. But this is within the context of a scene that otherwise confirms and affirms the structures of a scopic regime that is committed to negotiating scenes of normative blackness as hostile, violent, drug-ridden, hypersexualized, and hypermasculinized. And even in this blackest of black spaces, encoded in the most aggressively banal and predictable significations of the ghetto, the white body will always assert order and control over the black body. It will always demand the authority to make the space its own. Because whiteness always demands something of blackness—nurturing, rescuing, labor—the black body is thus always to be available for the use of whites. By the end of this scene, King has asserted his racial and spatial authority as he begins to reconstitute the gang structure along the lines of a hedge fund company.

Later in the film, hopeless that his innocence will ever be proven and having argued with Lewis, King returns to the Crenshaw Kings. Once more in blackface, though now dressed in dark clothes without any of the comic edge supplied by the lurid colors of his previous incarnation, King is at the point of becoming a member of the gang (fig. 11.5). Though this scene still relies on the comic inversions of blackface seen previously, it takes a far more serious turn. Russell asks: “You ready to get put on the hood?” to which King replies, “I’m rollin’!”

The scene cuts immediately to a party with a montage sequence of King drinking, smoking, dancing, fooling around with a young woman, and finally being handed a gun. In voice-over, Russell explains: “Once you step through this threshold, motherfuckers are ready to kill for you. I mean a whole fraternity of motherfuckers is gonna have your back. But there’s only one way outta this. That’s when your casket drops into the ground. So from this day forward you have eternal protection until your eternal demise.” A cut shows Russell looking intently into King’s face. Pointing to the front door, Russell says: “We’re dead-ass serious about what we do. And if you go through that threshold and make it back we’re gonna be dead-ass serious about you.”

This talk of threshold returns space, spatiality, and the boundary to the critical center of our analysis of race and identity. James King is in blackface, playing out a white fantasy of “nigga” blackness. But once he completes his initiation—once he steps through the threshold and moves beyond the boundary—his whiteness will be forever compromised. Having given up all hope, King is prepared to take that final step, to embrace suffering and cede his whiteness. For King, fulfilling the narrative and visual logic of Hollywood, to be black is to have no path to redemption. But fulfilling that other well-worn narrative path of Hollywood, at the final moment of exchange, King is rescued by his faithful black friend as Lewis reaches Russell’s house in time to dissuade King from his course of action: “James, you’ve got a choice right now. You’ve got the right path, you’ve got the wrong path. Make the right decision James.” King does, and he leaves with Lewis. Once they are in the car together, King reverts from the heavy-handed, hard-drinking, dope-smoking gangsta to the panicky, fearful milquetoast he was previously. Having been saved by the good and faithful Lewis, King reassumes the coded visual and linguistic signifiers of whiteness. Indeed, it is, in fact, King’s whiteness that Lewis has redeemed.

Just as the bounded space within The Birth of a Nation is traversed by whites at will, so too in Get Hard, as demonstrated by King’s moving in and out of the “ghetto,” there is no space that is not ultimately available to the white body, even if it demands blackface as payment for entry. However, there is one moment when King’s whiteness has nowhere to retreat and becomes fully feminized and fully victimized. As part of his reconfiguring of the Bel Air mansion as a prison, Lewis has turned King’s tennis court into a prison exercise yard, in which King becomes wholly subject to the disciplinary violences of a reconfigured racial authority. As Lewis literally acts out a conflict between a black and a Latino prisoner, King is pushed from one to the other and determined solely by his whiteness, refused any control of space that is constructed as a field of sexual as well as racial collapse and reconstitution.

His moment of safety comes when he is adopted by a third character, a gay character, who claims King as his own sexual property. James King’s overriding and repeated anxiety—the critical node of his abjection and suffering—is to be made the victim of sexual assault. Stuck in the prison yard, King’s whiteness is no longer the determining factor in the legitimacy of occupation of space—it can no longer assert its unexamined authoritative presence either to occupy spaces it chooses to or to demarcate the occupation of space by others. It is in this disruption of space that we see enfolded the disruption of whiteness and heteromasculinity; to lose control of space is to lose previously held racial and gendered power. Predicated on the profound linkage between space, power, and sexuality, the loss of spatial authority carries with it the loss of racial and sexual authority. In that sense we might read King’s sexual anxieties as second-order significations over the loss of racial and spatial authority. The singular and obsessive fear of sexual assault is mediated through the critical boundary of race, for the certainties of race collapse through the realization of and subjection of the self to sexual desire. The film begins with, and returns unendingly to, this neurotic fear revealing (and reveling in) its fundamental fascination. When James King first encounters Darnell Lewis and tells him that he will be going to San Quentin, Lewis reacts in horror:

You know what, let me give you my statistical analysis. You going to San Quentin, there’s a hundred percent chance you’re going to be somebody’s bitch. Ten years of this [he slams one hand into the other repeatedly]. You know what that is? That’s a big ass black man on your pale white ass [he repeats the gesture even more aggressively] ugh, ugh, ugh, ugh. You [he gestures to King and affects a whiny, high-pitched voice]: “No, I don’t want any more, stop, that’s enough!” Too late, he done tagged the next guy in. [He gestures even more rapidly and aggressively with his hands.] That’s like a rabbit. You don’t want him no more, so now here comes the guy who wants to rub your face. Guess what, you can look forward to ten years of it.

Sometime later, having tried in vain to teach him to fight, and with only twelve days before he is incarcerated, Lewis decides that there is only one other option for King: “I got a plan. You’re gonna learn how to suck dick.” Over lunch at “LA’s number one gay hook-up scene,” Lewis explains that, “bottom line, we’re talking about survival,” and therefore King must go to the bathroom and “politely” ask someone, “Do you mind if I give you a little head?” Exhibiting that dizzying combination of neurotic fear and phobic fascination, the film has King on his knees in a bathroom stall with a pickup from the restaurant. In an extended slow-motion sequence, with his eyes tightly closed and his mouth gaping open, King moves his head toward the man’s groin. Inching ever more slowly forward, the teasing possibility of the transgression of this final boundary is drawn out for as long as possible. Inevitably, however, at the very last moment, King turns his head away in horror. Returning to the table and admitting his failure, Lewis demands loudly of King: “Are you ready to get hard?” to which King replies, “I am ready! I am ready to get hard! I’m gonna show you how hard!” Lewis responds: “That’s what I want to hear so let’s go home and get hard!” Having been granted the pleasures and possibilities of a transgression ultimately refused, it is not difficult to imagine that the standing applause given to King and Lewis by the other diners as they leave the restaurant is really an eruption of congratulatory relief demanded of the audience by the film itself.

As the boundaries (both figurative and literal) of race, space, and sexuality are structured, threatened, dismantled, and reconstituted, their visual encoding constitutes the social and discursive parameters of whiteness, blackness, and heteronormativity. As the contradictions in Griffith’s film rupture its drive for textual purity, Get Hard labors to convince viewers of its knowing postracial sensibility while mired in the trammeled racial representations it purports to undermine. But more than this, these texts live, work, breathe, and speak whiteness together. I am, of course, not suggesting that Get Hard was explicitly influenced by The Birth of a Nation or that it is even in any way self-consciously responding to it or is overtly racist in that sense. Indeed, by playing with recognizable tropes and discourses, Get Hard attempts to situate itself as beyond the vulgarities of Griffith’s unreconstructed racism. But there is a mutually constitutive reciprocity between the texts that is constituted by the film’s relationship to the spectator, the history of film, and indeed the entire history of Western culture. In other words, these objects are being constantly reconstituted as they turn toward and away from each other, as they encounter reflections, refractions, and resonances. It is clear that the narratives of race critical to The Birth of a Nation are present in any number of ways in contemporary cinema—indeed across contemporary culture—without those links having to be in any way deliberate or necessarily obvious. As with The Birth of a Nation, a critical sense-making structure in Get Hard is the spatialization of race in service to a scopic regime that asserts the normativity of the white, heterosexual gaze. By getting spectators to look (and in the looking, of course, is everything), sexuality, race, and power collide in the demarcation of space. There is no way to avoid our interpolation into the communities of meaning that surround the text. It is not so much that we approach the text to read it dialogically, but that dialogism structures the text. It is our job to unpack the dialogical processes in order to understand the broader relationships between the social, the political, and the aesthetic. The “singular [generic] text” can only be fully understood when situated in relation “principally to other systems of representation.”[25] These texts make claims to certain meanings that we can assess, understand, interpret, and reinterpret.

Finally, and perhaps most significantly, both The Birth of a Nation and Get Hard are movies that assert white suffering as their dominant visual, discursive, and rhetorical trope. The presence and function of blackface speaks to deep anxieties over the white body being demeaned, dehumanized, beaten, and abused. The attendant tropes of white victimhood can be read in different ways. For instance, for The Birth of a Nation’s audience in 1915, it might be surrounding discourses of post–Civil War Southern resentment; for Get Hard, we might point to debates surrounding affirmative action. But it is all too easy to see the fundamental shared structures of whiteness that inform both of those broader discourses. Constructed through the arrangement of spaces of trauma (battlefields of the South, the prison cell and prison yard), both films triangulate race, space, and suffering. Equally, there is always present a profound fascination for those spaces in which whiteness may play out in fantasies of abjection, promising the compelling vision and experience of boundary collapse. What the assault on the decorous boundaries of white life in both The Birth of a Nation and Get Hard conveys—beset as the films are by the specters of racial abjection and sexual violence—is that there is no redemption without suffering. Though Get Hard might grant the modern eye a set of images that allow for the playing out of white fantasies about being black that The Birth of a Nation could only hint at, both films share the most profound assertion that it is white suffering—not black—that is at the heart of the American experience.

David C. Wall is Associate Professor of Visual and Media Studies at Utah State University. He is editor with Michael T. Martin of The Poetics and Politics of Black Film: Nothing But a Man, and editor with Michael T. Martin and Marilyn Yaquinto of Race and the Revolutionary Impulse in The Spook Who Sat by the Door.

- Anna Everett, Returning the Gaze: A Genealogy of Black Film Criticism (Durham, NC: Duke University Press 2001), 59. ↵

- Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism (London: Verso, 1998). ↵

- James Snead, “Birth of a Nation,” White Screen/Black Images: Hollywood from the Dark Side (New York: Routledge, 1994), 39. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- This idea is explicated more widely and in relation to history film generally in Michael T. Martin and David C. Wall, “The Politics of Cine-Memory: Signifying Slavery in the History Film,” in A Companion to the Historical Film, ed. Robert A. Rosenstone and Constantin Parvulescu (Chichester, UK: John Wiley), 445–467. ↵

- Gerald R. Butters, Black Manhood on the Silent Screen (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2002), 66. ↵

- Ed Guerrero, Framing Blackness: The African American Image in Film (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1993), 15. ↵

- Ella Shohat and Robert Stam, Unthinking Eurocentrism: Multiculturalism and the Media (New York: Routledge, 1994), 180. ↵

- Martin Flanagan, Bakhtin at the Movies: New Ways of Understanding Hollywood Film (Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009), 5. ↵

- Michael Holquist, Dialogism: Bakhtin and His World (London: Routledge, 2002), 18. ↵

- Ibid., 23. ↵

- Cedric Robinson, Forgeries of Memory and Meaning: Blacks and the Regimes of Race in American Theater and Film before World War II (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2007), 98. ↵

- Quoted in ibid., 104. ↵

- Flanagan, Bakhtin at the Movies, 183. ↵

- Peter Stallybrass and Allon White, The Politics and Poetics of Transgression (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1988). ↵

- Susan Courtenay, Hollywood Fantasies of Miscegenation: Spectacular Narratives of Gender and Race (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2005), 62. ↵

- Robert Lang, “The Birth of a Nation: History, Ideology, Narrative Form,” in The Birth of a Nation, ed. Robert Lang (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1994), 17. ↵

- Courtenay, Hollywood Fantasies, 64. ↵

- As well as the complicated visual spectacles of race that blackface minstrelsy embodied and demanded from both performer and audience, every element of popular and material culture of the nineteenth century—from advertising to postcards to children’s games to food products to sheet music and on and on—featured black bodies in myriad states of subjection, abjection, and transgression. This ubiquitous presence in American visual culture throughout the period (and onward to the present day, we might add) is testimony to its compelling fascination for the white spectator. ↵

- See my longer discussion of Eastman Johnson’s painting in David Wall, “Transgression, Excess, and the Violence of Looking in the Art of Kara Walker,” Oxford Art Journal 33, no. 3 (2010): 277–299. ↵

- Courtenay, Hollywood Fantasies, 50. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- There has been much critical work over the last couple of decades in this area, but readers unfamiliar with the broader arguments around the complexity of blackface as a cultural and racial modality should begin with the groundbreaking Eric Lott, Love and Theft: Blackface Minstrelsy and the American Working Class (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993). ↵

- This argument that blackface historically provided a complex arena for whites to act out a myriad of social, cultural, and racial anxieties and ambivalences has been asserted and complicated by any number of writers over the last couple of decades, not least in Lott, Love and Theft. ↵

- Robert Stam, Film Theory (Walden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2000), 203. ↵