7 The Rhetoric of Historical Representation in Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation

Lawrence Howe

Along with his many advances in cinematic narrative, D. W. Griffith deserves credit for consistency in the face of pointed criticism about his film’s use of history. Right up to the last year of his life, thirty-two years after the release of The Birth of a Nation, he maintained a defensive posture: “In filming The Birth of a Nation, I gave to my best knowledge the proven facts, and presented the known truth, about the Reconstruction period in the American South. These facts are based on an overwhelming compilation of authentic evidence and testimony. My picturisation of history as it happens requires, therefore, no apology, no defence, no ‘explanations.’”[1]

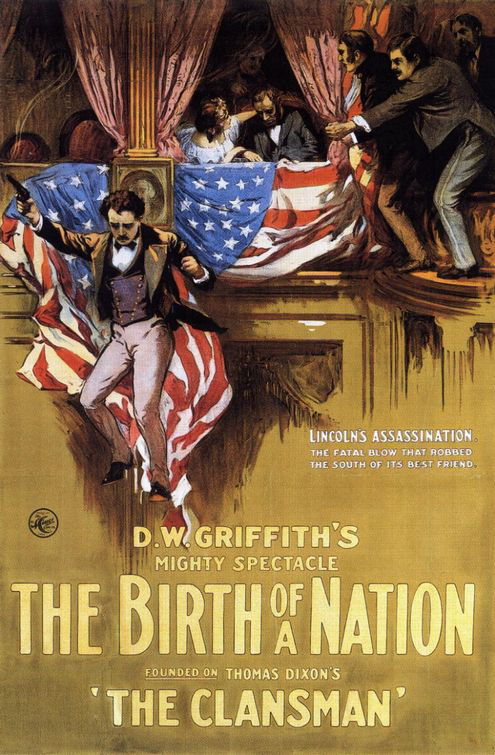

In emphasizing his use of “proven facts” and his “compilation of authentic evidence and testimony,” Griffith downplays another important fact: his film is primarily a melodrama of two families from opposites sides of the regional divide before, during, and after the Civil War. Although the Civil War and Reconstruction are undeniable historical facts, Griffith’s representation of them is drawn from the tradition of the Southern romance, largely influenced by Walter Scott’s Waverly novels and the plantation myth that many Southerners nostalgically embraced after their defeat in the Civil War. Indeed, The Birth of a Nation is a reiteration of a very ambitious fiction. Thomas Dixon, a fellow Southerner, adapted his two novels The Leopard’s Spots and The Clansman into a theatrical drama, and Griffith adapted this stage work into the vexed landmark of American cinema. Following Dixon’s lead, Griffith originally titled his film The Clansman, which he altered to square up with the Dunning interpretation of the United States as a nation born not out of the American Revolution but from the crucible of the American Civil War. Thus, despite Griffith’s insistence that he constructed a sound historical account, the film promotes a Southern mythology that extols the virtue of white resistance to black oppression. In casting blacks as primitive and morally deficient Others, the film shares the pernicious ideology of its source material. This troubling content complicates any discussion about the merits of its cinematic narrative technique.

Still, despite the film’s basis in melodrama, Griffith’s claim that his film is a “picturisation” of history is understandable, for he assiduously worked plenty of history into it. Indeed, the emphasis that he repeatedly placed on the film’s historicism is, I contend, an important tactic in an overarching rhetorical strategy. Griffith and Dixon, in tandem, sought to imbue the film with the authority of history both diegetically and extradiegetically to bolster the film’s argument about white supremacy. The collaboration between filmmaker and novelist serves to call attention to an intellectual debate about history’s synthesis of science and art that, as Hayden White has suggested, polarized intellectuals at the end of the nineteenth century.[2] In taking up this question, White emphasizes that the historian frames content within recognizable narrative forms with specific structures of “emplotment” that condition its representation of history as either epic, romance, comedy, tragedy, or satire. Concluding, he writes, “We may say, then, that in history—as in all of the human sciences—every interpretation has ideological implications.”[3] Thus Dixon’s romance of white Southerners to re-ascendancy is a ready form for Griffith to adapt to a historical cinematic narrative rife with ideological interpretation.

In 1915, the cinematic approach to history was arguably naïve, as Griffith’s statements suggest. And cinema’s tendencies to focus on identifiable protagonists and antagonists and to oversimplify complex events, their causes, and consequences drew criticism from historians throughout the twentieth century. In recent decades, however, several historians have reconsidered the potential virtues of film as a medium of historical representation, leaving the field in another round of debate. Robert Rosenstone, one of the most vocal proponents of history on film, cites the oppositional views of philosopher Ian Jarvie and historian R. J. Raack as exemplary of the divide. Jarvie criticizes film as discursively weak due to its “poor information load,” resulting in “a descriptive narrative” that lacks the kind of polemical complexity that he sees as the arena of serious historical practice. In contrast, Raack sees film as a remedy to the linearity and narrow focus of “traditional written history,” citing film’s “ability to juxtapose images and sounds, . . . its quick cuts to new sequences, dissolves, fades, speed-ups [and] slow motion” as necessary techniques for rendering the lived experience of history.[4] Rosenstone grants that Raack’s position is an unorthodox one, but he also finds merit in the idea that cinema’s command over time and space enables it to provide insight into other eras and places. And he questions Jarvie’s criticism that cinema lacks information, noting that the kind of information may be different from what historians have traditionally valued; but from his own experience of working on a feature film and a documentary drawn from his scholarship, he has come to see cinematic data as quite rich in what it illuminates to the viewer. Following Rosenstone, Alison Landsberg argues that film can foster “affective engagement” that has the “capacity to bring the past literally into view, to make it feel real, to flesh it out.” But she hastens to note that, “in some cases it offers the illusory promise that the viewer can slip back into the past and ‘know what it was like’ by means of a simplistic, facile identification with an onscreen character”—precisely the point on which many historians have often rested their critique.[5] The distinction, for Landsberg, lies in the filmmaker’s sense of responsibility to evoke “an embodied and powerful mode of engagement that might be conducive to the acquisition of historical knowledge.”[6]

Griffith’s responsibility is precisely the focus of my argument. The degree to which the filmmaker and novelist contrived to couch the film’s racist polemics as historically objective has received considerable critical attention. But these examinations have stopped short of a full analysis of how the film’s historical representations serve a rhetorical design. In this essay, I aim to move the critical debate in that direction. The point that I will make about the film’s historicism is a fairly simple one, but a crucial one nonetheless: Griffith’s multiple forms of historical representation are scaffolded in order to persuade his audience of the film’s reliability and historical authority. Among these various forms of representation, the scene of Lincoln’s assassination is both central to the film’s diegesis and key to its rhetorical design. In particular, Griffith’s exploitation of his audience’s position as spectators during this pivotal scene was a rhetorically shrewd, though ultimately deceptive, manipulation of the viewer’s perspective.

Griffith’s claim that he relied on “proven facts” and “authentic evidence and testimony” suggests that he sees history as a set of uncomplicated givens, with little or no regard for the contingency of interpretation, the importance of context, and the inevitable ideological bias of any narrative framework that contains historical “facts.” James Snead argues that Griffith’s use of history was “not casual,” but rather “a self-conscious aim of The Birth of a Nation to write history with cinema, particularly with its so-called ‘historical facsimiles,’ which are both obtrusive and dilatory to the plot, but which are crucial to ideological, rather than narrative, aims.”[7]

I will address the historical facsimiles at greater length later in this chapter, agreeing with Snead that they are crucial. However, I argue that their importance is not only ideological but also rhetorical, which, as Mikhail Bakhtin argues, is a fundamental condition of prose narrative in the form of the novel.[8] Indeed, White, in noting the commonplace that “all historical accounts are ‘artistic’ in some way,” goes further to contend “that the artistic component in historical discourse can be disclosed by an analysis that is specifically rhetorical in nature, . . . [deploying] a ‘code’ by which the reader is invited to assume a certain attitude toward the facts and the interpretation of them” (emphasis in original).[9] To achieve his historicist strategy, Griffith deployed various tactics that registered the film as a reflection of what he took to be historical fact; however, that historical narrative is framed in the terms of a rhetorical code.

According to Michael Rogin, “Griffith, claiming historical documentary status for his own fiction, made film the ultimate authority. Fully realizing film’s power to seize the audience, Griffith replaces history with the illusionistic, realistic, self-enclosed, cinematic epic.”[10] Although I agree with much of what Rogin contends, I argue that the filmmaker did not replace history as much as he constructed a version of history, selecting and framing historical elements in order to transmit identifiable signals to the audience. And his intended audience also accepted Griffith’s account of history and even approved of his deliberate blending of history with melodrama. As with all films that are considered historical, “audiences recognize the existence of a system of knowledge that is already clearly defined—historical knowledge, from which film-makers take their materials,” drawing on a common heritage that functions as “‘historical capital,’ and it is enough to select a few details from this for the audience to know that it is watching an historical film.”[11] It is the structure of the historical gestures in The Birth of a Nation and their effect on the audience on which my analysis will focus.

A Divided Nation Finds a Common Audience

In emphasizing the film’s designed effect on the spectator, it is important to note that, for Griffith, the audience was composed of exclusively white spectators from the North and South. The explicit purpose of Griffith’s narrative is to reunite the divided nation by showing how white families on both sides of the regional divide, represented by the Stonemans and Camerons, shared the toll of the Civil War. Both families lose sons in the Civil War; moreover, Tod Stoneman (Robert Harron) and Duke Cameron (Maxfield Stanley)—antebellum “chums” now cast as Union and Confederate enemies—die in a quasi-erotic fraternal embrace that immortalizes their earlier affinity for each other. The compassionate heroism of Confederate Colonel Ben Cameron (Henry B. Walthall), in providing comfort for a fallen Union soldier, projects his honorable character, suggesting the South’s worthiness of the North’s respect.

In focusing the second half of the narrative on the consequences of Southern defeat, the film implies the racial identity of its intended audience, emphasizing that whites of both regions had a mutual stake in restoring the racial order that Griffith posits as natural. The occupation of the South by Northern troops exposes the daughters of both families to the dangers of black male sexuality. In her study of spectatorship in early cinema, Miriam Hansen notes that, despite the efforts of early filmmakers such as Griffith and other promoters of the industry to endorse film as a universal language, it was not the democratically diverse art form they imagined. Applying theories of the public sphere, Hansen argues that the cinema’s influential imagery produced an alternative public sphere that minimized class and ethnic diversity: “The invocation of the universal-language myth came to mask the institution’s suppression of working-class behavior and experience. . . . By taking class out of the working class and ethnic difference out of the immigrant, the universal-language metaphor in effect became a code word for broadening the mass-cultural base of motion pictures in accordance with middle-class values and sensibilities.”[12]

Furthermore, The Birth of a Nation did not simply promote narrow class-based values; rather, it stressed the virtues of a white-centric society. Although this had long been a constituent of the Southern ethos, the film’s release occurred in the midst of the first wave of the “great migration,” marking the arrival of many African Americans to Northern industrial cities. This demographic shift stirred anxieties of working-class whites about competition for jobs and of middle-class white homeowners fearful of a loss of property value from integrated neighborhoods. So the message of Griffith’s film about white virtue and privilege found a receptive audience among white spectators across the nation.

The film’s postbellum narrative traffics in denigrating African American stereotypes as justification for the rise of white vigilantism to restore the ostensible order that Reconstruction violated. Needless to say, black spectators have no opportunity to identify with a narrative that unilaterally casts black characters in roles of moral degradation. In a close reading of the famous sequence in which Gus pursues Flora, Manthia Diawara highlights the dilemma for black spectatorship of The Birth of a Nation: “At issue is . . . the contradiction between the rhetorical force of the story—the dominant reading compels the black spectator to identify with the racist inscription of the black character—and the resistance, on the part of Afro-American spectators, to this version of US history, on account of its Manichean dualism.”[13] Indeed, William Walker, a black spectator interviewed in Kevin Brownlow and David Gill’s 1992 documentary, D. W. Griffith: Father of Film, reported feeling erased from the national narrative upon viewing the film in 1916 in a black theater: “Some people were crying. . . . You had the worst feeling in the world. You just felt like you were not counted. You were out of existence.”[14] Walker’s subsequent desire suggests the potential consequences of the film, about which civil rights leaders had warned: “I wished somebody would not see me so I could kill them. I just felt like killing all the white people in the world.” Although Walker’s admission approaches the rage that Richard Wright would fictionally embody in Bigger Thomas, the notorious protagonist—and movie spectator—in Native Son, the violence that took place with the release of The Birth of a Nation was perpetrated by whites against blacks. Civil rights leaders warned about the likelihood of the film promoting violence. The accuracy of their foresight can be measured in the resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan. After lying dormant since the passage of three Enforcement Acts, which criminalized vigilante intimidation practices in the early 1870s, the organization rose again in the wake of Griffith’s film, its recruitment increasing steadily from 1915 and peaking in the mid-1920s.

Griffith may not have foreseen these consequences, but he did forge the film’s historical authority consistent with a racial ideology. At strategic intervals, the film constructs a series of historical gestures that project the racist melodrama as an authentic continuation of the historical representation. By capitalizing on the white audience’s sentiments and, especially, their position as spectators, Griffith’s historical representations are central to a rhetorical design that seeks to leverage the audience’s trust in the narrative’s biases. Once the film elicits that trust in its historical authority, it induces the audience to give credence to the full arc of the film’s narrative—the mythology as well as the history.

Framing Historicist Rhetoric

The historical gestures Griffith deployed in The Birth of a Nation are varied and sequential, designed to project authority. The film begins with extradiegetic historical references, laying the groundwork for its bona fides. Providing the backstory of slavery, an early intertitle declares that “The bringing of the African to America planted the first seed of disunion.” Despite eliding agency for the planting of this seed, the ensuing scene shows a figure in Puritan dress overseeing the importation of slaves, suggesting that New Englanders were primarily responsible. This is followed immediately with a reference to abolitionists—more meddlers from New England—who demanded the end of slavery. The narrative conveys no concern for the slaves, treating them as objects that the North has exploited.

The opening of the film’s second half parallels these polemics in its commentary on Reconstruction. A series of three intertitles introduce quotations from Woodrow Wilson’s magisterial A History of the American People to buttress the film’s historical validity. This historical commentary frames Reconstruction as the scheme of “adventurers” who “swarmed out of the North, as much enemies of the one race as the other, to cozen, beguile, and use the negroes” (emphasis added). The series of carefully selected verbs portray the Northerners as unscrupulous, and their deceptive practices were abetted by “congressional leaders” to effect “a veritable overthrow of the civilization in the South . . . in their determination ‘to put the white South under the heel of the black South’” (emphasis in the original). From this cause, the excerpts from Wilson’s narrative history conclude, “The white men were roused by a mere instinct of self-preservation . . . until at last there had sprung into existence a great Ku Klux Klan, a veritable empire of the South, to protect the Southern country.” The language of Wilson’s account of the Klan is telling: in the face of hordes of deceitful invaders, white Southern men were naturally “roused” by “instinct.” Indeed, the Klan seems to emerge on its own unbidden, albeit fortunately to right the corruption visited on the historian’s beloved South.

Wilson’s framing of both sides in coded language makes clear that the practice of history is an interpretive field, and the historian’s bias prompts him to read the record with compassion for his region and contempt for the cynical motivations of the Reconstructionists. But even allowing for regional bias, the praise of the Klan as “great” and a “veritable empire of the South” strikes a discordant note today, given what we know of the hateful terrorism Klansmen inflicted. Still, for Griffith, the president’s words are important validation because they square with the representations that his adaptation of Dixon’s narrative converts into vivid “picturisations.”

Indeed, Wilson’s authority lends credibility to the film’s case because he was not only the president of the United States at the time the film was released but also the first president to hold academic credentials. He held a PhD in history from Johns Hopkins University and had been on the history faculty at Bryn Mawr, Wesleyan, and finally Princeton, where he was also appointed university president. Thus, the inclusion of his words is an attempt to validate the film’s cinematic spectacle by attaching to it Wilson’s authority as de facto “historian-in-chief.” Prior to the release of the film, Griffith and Dixon also externally parlayed Wilson’s credentials to reinforce its historical status. Having known Wilson at Johns Hopkins, Dixon proposed an advance screening of the film for the president and members of his cabinet. Wilson agreed, granting the film the distinction of being among the first, if not the first, to have been shown in the White House. Dixon and Griffith took this occasion a step further by promoting the film with an unauthorized endorsement from Wilson. Although the film’s heroic depictions of the Ku Klux Klan’s terrorism match Wilson’s praise of the Klan, there is no corroboration that Wilson ever famously announced that The Birth of a Nation “is like writing history with lightning, and my only regret is that it is all so terribly true.”[15] Indeed, the controversy over the film was such a political liability for Wilson that he instructed J. P. Tumulty, his private secretary, to issue a statement “that he had at no time approved the film,” and in 1918 he deemed the film an “unfortunate production.”[16] But the frequency with which the approbation of the film as “writing history with lightning” has been assigned to Wilson indicates the effectiveness of the strategy that Dixon and Griffith had devised.

Still, as peripherally useful as the Wilson quotations within the film and his apocryphal endorsement are, they are also entirely uncinematic and supplementary to the film’s designed effect. The “picturisation of history” begins to emerge in the historical dramatizations, and these take three different forms. The first includes Civil War battle scenes, representations of historic events such as Sherman’s burning of Atlanta, and the siege of Petersburg. None of this was entirely new for Griffith. He had honed his representation of the spectacle of Civil War battles in short films prior to The Birth of a Nation. We know of twenty-seven short films that included Civil War battle scenes made in the United States from the onset of Griffith’s directing career in 1908 to the release of his epic film in 1915. Of those, twelve were written, produced, and directed by Griffith and included many of the actors and crew who collaborated on the Birth of a Nation—especially the cinematographer G. W. “Billy” Bitzer, with whom Griffith had pioneered his innovative visual narrative techniques. Griffith cast Henry Walthall in the leading role of Confederate soldier in three of those early films. Thus, the filmmaker and his company had considerable experience in filming and editing the drama of Civil War combat. Although Civil War films make up only a small percentage of early films, the topic fascinated audiences. But none, not even Thomas Ince’s fifty-minute film The Battle of Gettysburg (1913), compares to the epic sweep of The Birth of a Nation, which explicitly linked the war to the upheaval of Reconstruction and the consequent rise of the Ku Klux Klan. The Civil War scenes in The Birth of a Nation have impressive dramatic value, diegetically integrated with the primary plot of the central characters. However, the film’s military engagements are imagined representations, drawing on conventions of Griffith’s early filmmaking rather than on fidelity to the specifics of history. The battle scenes subordinate history to the nostalgic melodrama centering primarily on the Cameron family, making an emotional appeal about the honor and tragedy of war.

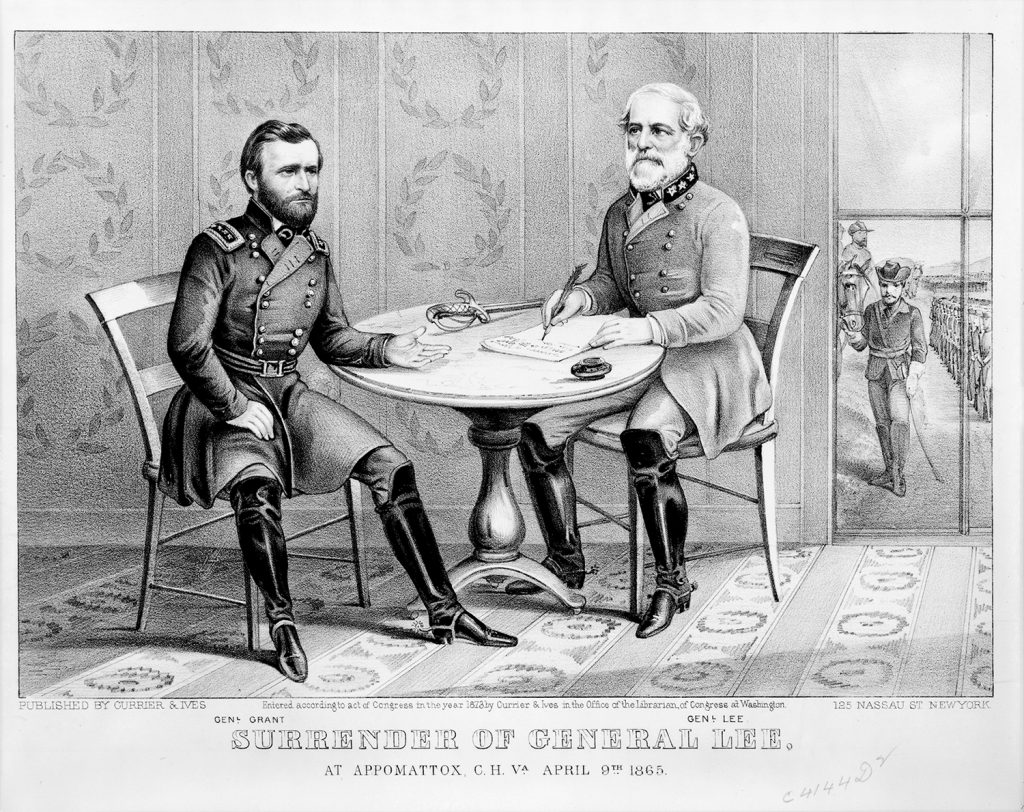

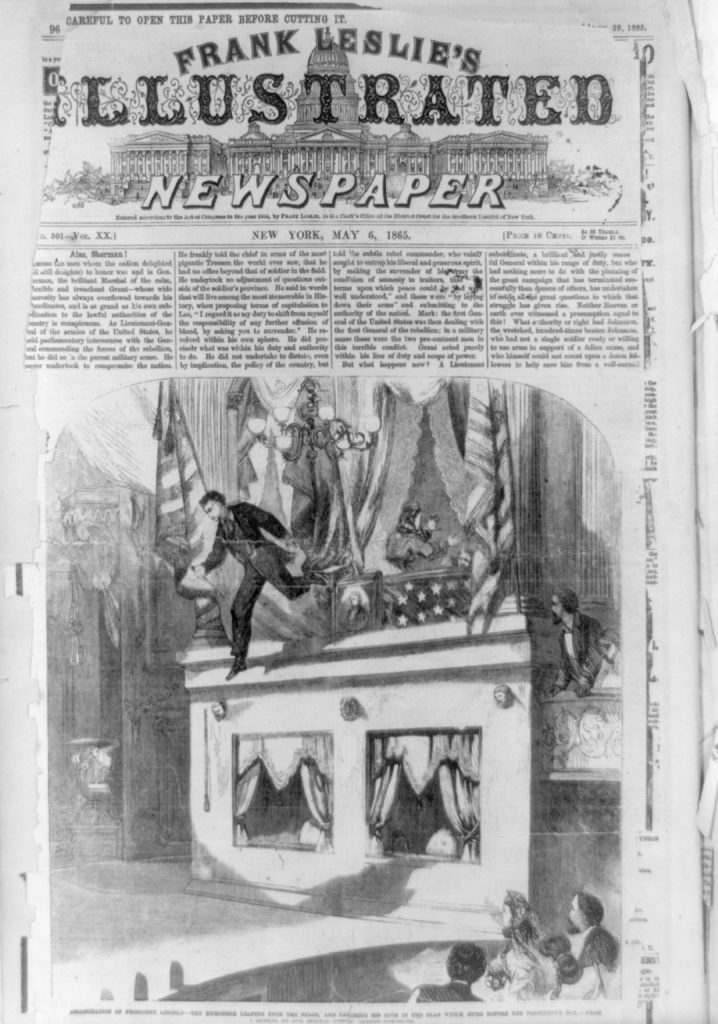

The second form of historical representation consists of tableaux of momentous national events, such as Lincoln signing the order to muster Union troops and Lee surrendering to Grant at Appomattox. Each of these scenes is introduced by an intertitle verifying it as “an historical facsimile” with a citation to a source text. As with the quotations from Wilson’s magisterial A History of the American People, the sources for the tableaux bolster the film’s historical authority. The scene of Lincoln signing the order to raise Union troops in his “Executive Office on that occasion, after Nicholas and Hay in Lincoln, A History,” cites a highly regarded source, given that the authors were Lincoln’s private secretaries. But, as Pierre Sorlin points out, their ten-volume work does not describe or depict the setting that Griffith screens for his audience. The historiographical source functions more as credence than reference. Spectators would not be inclined to seek out sources in order to be persuaded of the reliability of the scenes, because what they saw on the screen had been disseminated in mass-produced prints such as those sold for framing by Currier and Ives or reprinted in school texts (see figs. 7.1 and 7.2), making them highly familiar to the film audience. Other mass-produced images, such as Lincoln’s signing of the Emancipation Proclamation, are quite similar to Griffith’s screening of his proclamation mustering volunteer troops for the Union army, and thus similarly convey the historical reliability of the cinematic image.

Griffith’s screening of these representations amounts to the first form of “cine-memory” as Michael T. Martin and David Wall define it: “Class 1 cine-memory serves to affirm received assumptions and discourses about the past. It confirms the ideological certainties of the implied viewer, valorizes the beliefs, and conforms to the expectations of the audience. In doing so it functions to portray the hegemonic order as a consequence of nature rather than culture. Yet, the past it represents hides ideological assumptions and values that normalize the ‘reality’ it claims to express. Events appear fixed in time, discrete, simplistically framed, and analytically wanting.”[17] Hence, “class 1 cine-memory” visually reinforces a previous impression from experience or cultural document, which matches Griffith’s ostensible purpose in the film. By themselves, however, the tableaux render historical validity at the expense of cinematic drama. The nearly static images of highly recognizable historic figures signing documents, as well as their function as cine-memories that reaffirm viewers’ recollections of images in galleries and books, underscores the lack of cinematic quality in the tableaux.

The Lincoln Assassination as Common Historical Capital

Griffith warrants the Lincoln assassination scene as another “historical facsimile”; however, the historicism of this representation is notably different from the tableaux by being diegetically integrated within the film’s narrative. Thus, in its synthesis of the diegetic content of the Civil War battles and the extradiegetic content of the historical tableaux, the Lincoln assassination is a third form of historical representation that exerts a more complex and more vivid rhetorical leverage. Given its function, it seems rather surprising that critics have rarely commented on the assassination scene; only one, Mark Charney, grants it the central importance that I ascribe to it. If critics give the assassination any notice, most simply do so in passing, perhaps because, as Paul McEwan notes, “the outcome of the scene is preordained. The fact that the audience obviously knows what will happen means that rather than true suspense we have a sense of foreboding.”[18] Critics have focused, instead, on the melodramatic consequences of Reconstruction that proceed from the abrupt ending of Lincoln’s presidency. Rogin suggests as much, noting that “The death of Griffith’s Lincoln sets the white-sheeted knights of Christ in motion.”[19] His direct linkage acknowledges the central narrative purpose of the scene. According to Charney, the assassination scene serves Griffith’s larger purpose to highlight the documentary function of narrative cinema. However, he criticizes Griffith’s representation as “inevitably founded in theater not ‘facts’” (emphasis added).[20] Noting its “play-within-a-play” structure, Charney argues that the scene creates an “artificial distinction between what is real or ‘true’—Lincoln’s assassination—and what is representation or false—Our American Cousin.”[21] Contrary to presenting an objective representation of history, Charney claims, Griffith’s innovative techniques “emphasize the subjective development of character and plot through selective vision, and he never sacrifices the histrionic potential of a scene to faithful realism, despite his earnest insistence that his object is the ‘truth’” (emphasis added).[22] Given that Griffith had aspired to be a playwright before finding his way into the cinema, and that his film is an adaptation of Dixon’s theatrical play, we should hardly be surprised to find theatrical elements in the film. But while Charney’s analysis effectively unites form with ideology, I disagree with his critique of Griffith’s privileging of histrionics over “faithful realism.” To the contrary, Griffith conflates the two, paying meticulous attention to detail in his cinematic staging of the historic tragedy. This signals his fidelity to realism, while also maximizing the dramatic effect of the scene. Moreover, Griffith is not deploying realism for its own sake, but as a further investment in the rhetorical force of his film’s historical authority.

As has been often noted, the events of the film still had a hold on the national consciousness at the time of the film’s release. In Life on the Mississippi (1883), Mark Twain observed, “in the North one hears the war mentioned . . . once a month; sometimes as often as once a week.” And in the South, “[t]he war is the great chief topic of conversation. The interest in it is vivid and constant. . . . the war is what A.D. is elsewhere: they date from it.”[23] The Civil War, admittedly, commanded less attention thirty years after Twain’s visit to the South, but the release of The Birth of a Nation was timed to the fiftieth anniversary of the end of the Civil War, renewing the remembrance of the war and its aftermath. At the New York premiere of the film, theater attendants wore uniforms of the Union and Confederacy, while women ushers were dressed in period costume, theatrical flourishes that reinforced the film’s historical references, nostalgically embodying them for the audience.[24]

If the Civil War had emotional power, Lincoln’s assassination would have an even more galvanizing charge because it was a highly specific and personalized event. Unlike the war’s diffusely scattered and protracted experiences, the who, what, why, when, where, and how of the Lincoln assassination are extremely concrete details—especially the where. Griffith’s decision to dramatize the scene, rather than allude to it, as Steven Spielberg did in Lincoln (2012), capitalizes on the importance of the Lincoln assassination as a national event that generated an outpouring of mourning. Griffith’s return to the event as the closing scene of his first talking picture, Lincoln (1930), suggests its cultural staying power and its continued interest to the filmmaker. Martha Hodes’s recent study of the responses to this singular tragedy highlights the universal shock that many Americans experienced. Many were in disbelief, finding the murder of the president as an unfathomable turn of events, hard on the heels of the Union victory.[25] Numerous newspaper accounts, the only mass media of the day, reinforced the reality of what had occurred. Hodes also points out that, for those at Ford’s theater that night, the trauma was almost unrecoverable.[26] Given the assassination’s political and cultural impact, and the national mourning that swept the nation, it seems impossible to overstate the power of the assassination scene for the spectators of The Birth of a Nation. The New York premiere was only five weeks before the fiftieth anniversary of the assassination. And newspaper coverage of the anniversary included many eyewitness accounts including from some of the living cast members of the 1865 production of Our American Cousin, thus insuring the cultural significance of the film’s representation.

Griffith strives for a documentary effect from the outset of the scene, specifically announcing “the fated night of April 14, 1865” in an intertitle. The late arrival of the presidential party to the theater is similarly noted, and the moment just prior to the assassination is time-stamped and cross-referenced to the act and scene of the play. While these temporal details may prompt derision, as intrusions—explicit gestures meant to inform the audience, “you are watching the absolute truth . . . seeing is believing”—the attention to detail in this central scene, unmatched elsewhere in the film, suggests the heightened importance of historical precision.[27] As with the tableaux, an intertitle noting Ford’s theater as “an historical facsimile” introduces the scene, again citing Nicolay and Hay’s ten-volume Lincoln biography for authority. Like the tableaux, the image of the stage at Ford’s theater and the presidential box where Lincoln was slain would have been familiar to the audience from countless reports and illustrations of the historic tragedy. Mass media in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries were no match for the image saturation to which we have become accustomed. The prevalence of media images of events, such as the Kennedy motorcade in Dallas in 1963 or the falling twin towers of the World Trade Center in 2001, give rise to the phenomenon that Baudrillard terms hyperreality. Visually mediated memory was only getting underway with the medium that Griffith was pioneering. Still, what spectators had seen, heard, or read about the events at Ford’s theater had prepared them for the spectacle of Griffith’s representation, visually confirming their cultural impression of history. The film’s marketing campaign reflects the ways in which these images would register with the public. In addition to the movie posters bearing images of mounted and robed Ku Klux Klansmen, others featured the scene of John Wilkes Booth jumping from the presidential box to the stage after firing the fatal shot, graphically capitalizing on the drama of the assassination and recalling images in the popular press (see figs. 7.3 and 7.4).

In contrast to the historical tableaux, which struck objective postures, the Lincoln assassination scene not only is diegetically integrated within the narrative but also presents multiple point-of-view shots from the vantage point of Phil Stoneman (Elmer Clifton) and his sister Elsie (Lillian Gish), who attend the performance. Miriam Hansen notes that the iris shot of Booth enables the spectator to share Elsie’s view of the matinee idol and soon-to-be assassin through her opera glasses, highlighting this moment as “narrationally significant” for the subjective identification that it affords the spectator.[28]

Elsewhere, Hansen comments on the ability of classical cinema narration to expand “the possibilities of placing, or ‘positioning,’ the spectator in relation to the represented events, in both the figurative and literal sense of ‘position.’”[29] Although Hansen does not address it, the Lincoln assassination exemplifies this phenomenon. The composition of the scene grants the spectator both a subjective identification with the Stonemans and a quasi-omniscient perspective, intercutting their observations with details not visible to them or to other patrons at Ford’s theater on the fateful night. In a scene that runs slightly longer than five minutes, Griffith’s editing assembles fifty-five shots that move smoothly from the Stonemans taking their seats in Ford’s Theatre, through the performance of the light comedy on the stage and the Stonemans’ differing responses, to their enthusiastic applause when Lincoln (Joseph Henabery) and his entourage make their celebrated arrival, and to Elsie’s blushing observation of Booth (Raoul Walsh) on the balcony beside the presidential box. But the constructed sequence also reveals Lincoln’s bodyguard leaving his post to watch the performance onstage and Booth’s furtive access to the back corridor just vacated by Lincoln’s negligent bodyguard. We watch with dreaded anticipation as Booth, lurking outside the presidential box, takes his derringer from concealment within his coat. In other words, the film allows the viewer a privileged and informed line of sight, quite different from the vantage points of Phil and Elsie and the audience at Ford’s Theatre, who observe only what they can see from their theater seats. The film spectator’s privileged view amplifies not only the drama of the scene but also the persuasive power of the film’s historicism.

Most importantly, the scene leverages one additional element, a by-product of an often overlooked historical fact, giving it distinctive power over the spectator and heightened meaning to Hansen’s observations about cinema’s positioning of the spectator. Namely, Lincoln was assassinated in a theater. By grim coincidence, the film’s spectator watches the cinematic representation of that historic event while also seated in a theater that is similar in nearly every way to the one on-screen, except that the screen has replaced the proscenium stage. Griffith exploits the coincidence, creating a moment of reflexivity of the film’s consumption that postulates the illusion of subjective experience for the spectator. In effect, the film’s audience is imaginatively converted from a cinematic spectator into a witness to history, experiencing what Alison Landsberg calls a “prosthetic memory,” a “personally felt public memor[y] that result[s] from the experience of a mediated representation of the past.”[30]

The 1915 spectator’s experience would be equivalent to a contemporary viewer watching Paul Greengrass’s United 93 (2006) while onboard a transcontinental flight. According to Airlines for America, the industry trade organization, the airlines have taken it on themselves to exclude from in-flight entertainment programs even a fictional airplane disaster film—let alone a docudrama about the 9/11 tragic flight. Most recently, American Airlines, which was involved in the making of Sully (dir. Clint Eastwood, 2016), acknowledged that, despite its pride in the actions of the crew of Flight 1549, it would not screen the film as in-flight entertainment. American Airlines spokesperson Michelle Mohr represented the company’s logic: “It could be upsetting to someone flying with us or someone looking over and seeing those images, so we decided not to provide it.”[31] By ruling out airplane dramas as in-flight entertainment, the airlines implicitly acknowledge that the spectator’s position can be determined by more than gender, class, or race.

Griffith understood this and took advantage of the cinema spectator’s position in a theater to amplify the narrative effect of the Lincoln assassination scene, just as Buster Keaton did in Sherlock Jr. (1924) and Quentin Tarantino did in the climax of Inglourious Basterds (2009). The critical difference with The Birth of a Nation’s pivotal scene is that Griffith’s audience was prepared to feel the emotional weight and grasp the historical meaning of Lincoln’s assassination, affirming the film’s historical authority. Part of that preparation came through images and accounts to which the audience had been repeatedly exposed, and Griffith’s film strategically reinforces that content to drive home his film’s rhetorical design. The cinematic image of this infamous event brought the past into the spectator’s present point of view. For perhaps the first time in modern history, a cinematic representation of a historic event blurred the line between mediation and immediacy.

Arriving halfway through the film, this powerful cinematic moment is not the effect but rather the final catalyst of the film’s rhetorical purpose. The effect is explicitly announced about twenty minutes later in the scene titled “Riot in the Master’s Hall.” The intertitle warranting that the set is another “historical facsimile” from a newspaper photograph in 1870 leads the spectator to believe that what follows has been photographically documented. However, the scene employs the visual magic of a dissolve in which the empty legislative chamber, from the cited 1870 photograph, is gradually populated with its “negro majority” newly elected in 1871. Thus, it is not the documentary photograph but Griffith’s camera that places the spectator in the midst of unruly and uncouth black legislators who make a mockery of decorum and policy. Metaphorically drunk on newly acquired power, if not literally drunk on alcohol sipped from hidden flasks, the raucous assembly passes a series of orders that extend the social power of black citizens. This meeting culminates in a law that permits racial intermarriage, received with exultation by black members on the floor of the chamber who then turn their menacing gaze at Southern white women in the gallery. The mix of shots that Griffith assembles in this episode situates the viewer in various positions in the legislative chamber, granting multiple proximities to the unqualified members on the floor of the assembly as well as with the white visitors in the gallery, who flee the lurid looks of the black men now in power.

Taken together, all of Griffith’s historical gestures function as a visual syllogism, concatenating a logical deduction about the ostensible perversity of the Reconstruction South. The quotations from Wilson and the historical tableaux extradiegetically lay the foundation of the film’s claim of authority, magnified by the authenticity and reflexive immediacy of the representation of Lincoln’s assassination functioning as a mediating rhetorical warrant for the denigrating portrayal of the South Carolina legislature and, by extension, all African Americans. Where Griffith’s representations of history vivify images already embedded in public memory, his scandalous portrayal of the “Riot in the Master’s Hall” affirms white anxieties about the racial Other, especially magnifying the fear of sexual violation. In short, The Birth of a Nation leverages the reliability of the historical representations as ideological collateral that justifies extending the same credit to its racist propaganda.

The Rhetorical Payoff

Having piqued anxieties of race and sex, the film increases those tensions in the infamous scene in which Gus (Walter Long), a black Union soldier, approaches Flora Cameron (Mae Marsh). Even though Griffith has toned down the confrontation from Dixon’s novel—in which a mother and daughter are raped by Gus and subsequently kill themselves rather than live with the shame of their defilement—by reframing the encounter as Gus’s marriage proposal to Flora, both she and the audience have been primed to read his intentions as salacious defilement. It is, after all, Flora’s horror at Gus’s proposal, not his lust, that precipitates the suspenseful chase. But Griffith’s film does not require the overt depiction of Gus as a violent sexual beast; Flora’s vulnerability is perfectly understandable to the white audience. Her death, though a tragedy that must be avenged, is a lucky escape from the fate of Gus’s proposal. The abduction of Elsie by Silas Lynch (George Siegmann) reinforces the message by relying explicitly on white fear of the black man’s rapacity. Lynch’s predatory claim on the daughter of his political benefactor is both an unmistakable gesture of Griffith’s poetic justice for Austin Stoneman’s (Ralph Lewis) misguided leadership of radical Reconstruction and a sign of the fragility of the angelic Elsie in a society that has lost its sense of order.

The film’s climactic rescue scenes, triggered by multiple instances of white families besieged by rampaging black Union troops, track a rhetorical trajectory that inevitably leads to the erroneous conclusion that the Ku Klux Klan is the corrective justice to the abomination of radical Reconstruction. Through these dramatically suspenseful sequences, the film dispenses with claims to historical authority. Instead, these melodramatic tropes of damsels in distress are tacitly framed as objective fact on the earlier warrant of the film’s historical authenticity. In one sense, the film’s frenzy of anxiety is ironic, because it not only diverges from the explicitly brutal content of Griffith’s source text but also draws from stereotypical fear of black male lust. Even the enlightened Thomas Jefferson iterated that fear in Notes on the State of Virginia, when he analogized the black man’s desire for white women to the “preference of the Oranootan for the black women over those of his own species.”[32] Given what we now know about Jefferson’s long, and fruitful, relationship with Sally Hemmings, a slave of his late wife, his odd bestial analogy seems more like a projection of his own desire onto black men. The practice of white slave owners expanding their stock of slave property through rape was common enough to be condemned by the genteel Southern diarist Mary Chesnutt, suggesting white male desire as the source of the taboo against interracial sexuality as well as the motivation for the Klan’s vigilante terror in the guise of justice.

In the film’s climax, the promise of the Klan’s protection is fulfilled in two rescues of vulnerable damsels: Elsie Stoneman, abducted by the mulatto carpetbagger Lynch, and Margaret Cameron (Miriam Cooper), under siege by hordes of black soldiers. In parallel scenes, Dr. Cameron (Spottiswoode Aiken) and a Union veteran are poised to kill their daughters to prevent them from falling victim to the black soldiers’ lust. These gestures appropriate the maternal sacrifice of Margaret Garner—the historical inspiration for Toni Morrison’s novel Beloved—a slave mother who killed her daughter to save her from slavery. The maximum cathartic effect of this climax is achieved through Griffith’s decision to include multiple rescues. As he acknowledged in his autobiography, Griffith envisioned his film as a move beyond the melodramatic formula of rescuing a damsel in distress: “We had all sorts of runs-to-the-rescue in pictures and horse operas. . . . Now I could see a chance to do this ride-to-the-rescue on a grand scale. Instead of saving one little Nell of the Plains, this ride would be to save a nation.”[33] Griffith’s account of the narrative opportunity undercuts his insistence on the film’s historical reliability. Indeed, it suggests itself as evidence of Baudrillard’s claim that “history is our lost referential, that is to say our myth. It is by virtue of this fact that it takes the place of myths on the screen.”[34]

Melodrama was Griffith’s stock-in-trade, and in making a film that expanded his narrative reach to the fullest, he ensures that the Klansmen arrive in the nick of time to thwart sexual violation, both saving the nation and realizing the film’s emotional potential and its rhetorical objective. In the anticlimax, the surviving sons and daughters of the Cameron and Stoneman families unite as couples that will extend the specious common virtue of white supremacy for future generations. Most importantly, this closure effects Griffith’s and Dixon’s ideological vision by carefully guiding the audience to understand the narrative consequences as an inevitable process of the film’s historicism.

In this conclusion—indeed, in the last four reels of the film—Griffith no longer has need of the historicism that set up the argument. Contrary to Wilson’s apocryphal claim, the film is not writing history with lightning but reigniting myth with cinematic images of flaming torches. Baudrillard writes: “In the ‘real’ as in cinema, there was history but there isn’t any anymore. Today, the history that is ‘given back’ to us (precisely because it was taken from us) has not more of a relation to a ‘historical real’ than neofiguration in painting does to the classical figuration of the real.”[35] Baudrillard’s sense of loss stems from the multiplication of media images of a later era. But in light of Griffith’s use of history, Baudrillard’s embrace of an earlier time, when, he suggests, history was available in film without ulterior rhetorical motives, looks more like a false nostalgia. The Birth of a Nation gives us a reason to question whether the “real” was ever present in cinematic representations of history.

Coda: Beyond Griffith’s Racial Epic

We often hear the recurrent refrain that, although the United States still has a long way to go, the nation has made great progress in remediating the racism that is central to the narrative of The Birth of a Nation. This is not to say that history is no longer wrought to serve rhetorical purposes, cinematically or otherwise. Director Alan Parker faced criticism for his portrayal of white FBI officers as the heroes of Freedom Summer in Mississippi Burning (1988). That a film whose narrative was decidedly critical of racist backlash against the civil rights movement should get an important part of its story wrong suggests the difficulty of treating history cinematically. Glory (dir. Edward Zwick, 1989) was also questioned for granting the central point of view to Robert Gould Shaw (Matthew Broderick), the white officer in command of the Massachusetts Fifty-Fourth Regiment rather than to the black soldiers whose experience might have been the center of the narrative. Even Argo (dir. Ben Affleck, 2012), a historical film lacking conventional racial dynamics, has been criticized for several misrepresentations, especially minimizing the role of the Canadian embassy staff in the escape of the American hostages from Iran in 1980. On the positive side, Ava DuVernay’s Selma (2014) has been praised for avoiding hagiography of Martin Luther King Jr. and presenting a more evenhanded account of the political challenges of the landmark Selma-to-Montgomery voting rights march of 1965.

More recently, Nate Parker’s The Birth of a Nation (2016), a Sundance Vanguard Award winner, has garnered much critical praise for its account of the Nat Turner Rebellion. Parker’s film is historical both in its depiction of the 1831 slave revolt and historic in its potential to disrupt the Hollywood pattern of minimizing black-centric films. Indeed, Parker expressed his hope that the many distribution offers that his film attracted and the record-breaking deal that he accepted may strike a blow against white supremacy in the film industry.

Yet, as if Styron’s 1967 Pulitzer Prize–winning novel, The Confessions of Nat Turner, had not sparked enough controversy, Parker’s film has become embroiled in, if not eclipsed by, a troubling episode from the filmmaker’s past. Although Parker was acquitted of sexual assault charges as a Penn State student in 1999, it has since come to light that the accuser later committed suicide. As a result, press conferences for the film’s release veered away from questions about the film and its historical content to interrogate Parker’s role in the campus event years earlier, the charges, the trial, and the subsequent death of his accuser. The scandal strikes a dark note that ironically resonates with Parker’s decision to adopt—in fact, to reinscribe—the title of the most notorious film about race. But rather than challenging the racism of the earlier film, Parker’s film has been overshadowed by the publicity of his past, showing that the effects of Griffith’s historicism have rippled out to affect the present. What has remained obscured in the media glare is how the personal history of a contemporary black filmmaker has been reframed in the very terms that Griffith exploited: race, sex, and suicide. Although it would be far-fetched to imagine that the coincidence of factors in Griffith’s film and the media concern about Parker’s past was ideological payback, as Griffith’s retribution for Parker’s attempt to project a historical counternarrative repurposing the 1915 title, the unfolding treatment of Parker’s film indicates that, at the very least, the ideological vestiges of the first The Birth of a Nation are difficult to shake. The United States may have achieved a degree of racial progress, but the residue of a 1915 “picturisation of history” lingers.

Lawrence Howe is Professor of English and Film Studies at Roosevelt University. He is author of Mark Twain and the Novel: The Double-Cross of Authority, and editor with James Caron and Ben Click of Refocusing Chaplin: A Screen Icon through Critical Lenses.

- Quoted in Robert Lang, “The Birth of a Nation: History, Ideology, Narrative Form,” in The Birth of a Nation, D. W. Griffith, Director, ed. Robert Lang (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1994), 3. ↵

- See Hayden White, “The Burden of History,” in Tropics of Discourse: Essays in Cultural Criticism (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1978), 27–50. ↵

- Hayden White, “Interpretation in History,” in White, Tropics of Discourse, 61–62. ↵

- Robert A. Rosenstone, “History in Images/History in Words: Reflection on the Possibility of Really Putting History onto Film,” American Historical Review 93 no. 5 (1988): 1176. ↵

- Alison Landsberg, Engaging the Past: Mass Culture and the Production of Historical Knowledge (New York: Columbia University Press, 2015), 29. ↵

- Ibid., 16. ↵

- James Snead, White Screens/Black Images: Hollywood from the Dark Side (London: Routledge, 1994), 41. ↵

- M. M. Bakhtin, “Discourse in the Novel,” in The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays, ed. Michael Holquist, trans. Caryl Emerson and Michael Holquist (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1983), 267–270. ↵

- Hayden White, “Historicism, History, and the Imagination,” in White, Tropics of Discourse, 107. ↵

- Michael Rogin, Blackface, White Noise (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996), 77. ↵

- Pierre Sorlin, The Film in History (Totowa, NJ: Barnes and Noble, 1980), 20. ↵

- Miriam Hansen, Babel and Babylon: Film Spectatorship in the American Silent Film (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1991), 78. ↵

- Manthia Diawara, “Black Spectatorship: Problems of Identification and Resistance,” in Film Theory and Criticism, 7th ed., ed. Leo Braudy and Marshall Cohen (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009), 769. ↵

- Linda Williams, Playing the Race Card: Melodramas of Black and White from Uncle Tom to O. J. Simpson (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2001), 128. ↵

- Michael Rogin, “‘The Sword Becomes a Flashing Vision’: D. W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation,” in Lang, The Birth of a Nation, D. W. Griffith, Director, 251. ↵

- Arthur S. Link, Wilson: The New Freedom (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1956), 253–254. ↵

- Michael T. Martin and David C. Wall, “The Politics of Cine-Memory: Signifying Slavery in the History Film,” in A Companion to the Historical Film, ed. Robert A. Rosenstone and Constantin Parvulescu (Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2016), 448–449. ↵

- Paul McEwan, The Birth of a Nation (London: BFI/Palgrave, 2015), 42. ↵

- Rogin, Blackface, White Noise, 76. ↵

- Charney, “‘Picturizing’ History: The Assassination of Lincoln in D. W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation,” South Carolina Review 22, no. 2 (Spring 1990): 58. ↵

- Ibid., 62. ↵

- Ibid., 58. ↵

- Mark Twain, Life on the Mississippi (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996), 454. ↵

- Arthur Lenning, “Myth and Fact: The Reception of The Birth of a Nation," Film History 16, no. 2 (2004): 123. ↵

- Martha Hodes, Mourning Lincoln (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2015), 56. ↵

- Ibid., 48–49. ↵

- Snead, White Screens/Black Images, 41. ↵

- Hansen, Babel and Babylon, 150. ↵

- Ibid., 80. ↵

- Alison Landsberg, Prosthetic Memory: The Transformation of American Remembrance in the Age of Mass Culture (New York: Columbia University Press, 2004), 3. ↵

- Mia Galuppo, “American Airlines Assisted Sully, but Won’t Show the Movie on Its Planes,” Hollywood Reporter, September 9, 2016. ↵

- Thomas Jefferson, Notes on the State of Virginia, in Thomas Jefferson: Writings, ed. Merrill D. Peterson (New York: Library of America, 1984), 265. ↵

- D. W. Griffith, The Man Who Invented Hollywood: The Autobiography of D. W. Griffith, ed. Thomas Hart (Louisville, KY: Touchstone, 1972), 88–89. ↵

- Jean Baudrillard, “History: A Retro Scenario,” in Simulacra and Simulations, trans. Sheila Faria Glaser (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1994), 43. ↵

- Baudrillard, “History: A Retro Scenario,” 45. ↵