6 Serial Melodramas of Black and White

The Birth of a Nation and Within Our Gates

Linda Williams

During the stimulating discussion that inspired this book at the 2015 symposium about The Birth of a Nation (1915), someone asked whether there was a “grand narrative about race.” I think that there is such a thing, but it is not one single narrative—it is several. Of course, The Birth of a Nation is a huge part of this narrative, but we misunderstand it if we think it is the beginning. We misunderstand it also if we think it is pure and simple racism, for racism is neither pure nor simple. Most importantly, we—black, white, and all others who find themselves hailed as racial subjects—need to understand how each new part of the narrative is in dialogue with its past parts. The story both accretes and repeats over time. I tend to think of it as a kind of serial argument that begins with a thoroughly maternal expression of pity for the wrongful suffering of black lives and is answered by an equally thorough patriarchal rejection of such sympathy. To put it simply and in a way that suggests how stuck the United States is in this melodrama’s repetitive forms, it is an argument that begins by stating that, at the time of its first iteration, the word American did not include slaves and that Americans should pity the suffering of helpless slaves at the whims of evil white masters.

This was the first installment in the serial melodrama of black and white. It was written by a white mother of seven who saw in the sufferings of slaves something like the suffering of her own sick or dying children. It is the melodrama of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. The climax of this suffering was the beating death of Uncle Tom himself, the slave who in the future would forever be hated by blacks for staying faithful to his “good” master, but who we should not forget was also at one time revered by whites and blacks for defying his evil master by saying that his soul belonged to God. This initial argument for the humanity of suffering slaves was answered, dialectically, in American popular culture by its reversal: the portrayal of the suffering of whites at the hand of blacks. In a nutshell, this is the original argument. It begins with a claim that black lives matter. It is refuted by The Birth of a Nation, which says black lives do not. It has been going on, in one form or another, since 1852.

The argument plays out in popular culture over the time of US history since before the Civil War, and, sadly, it continues to the present. At first it is an argument between whites about blacks: Are they saintly sufferers, or are they evil, rapacious villains? The terms of the argument were set by its first, incendiary claim that blacks are human—not necessarily deserving of rights but human nevertheless. But over time, black voices have joined in to demand rights. In this chapter, I will isolate the first moment in popular film culture when an African American voice had its say. It can only have its say, I argue, within the terms of the argument already established: effectively the issue of whether, or how much, as I have already suggested, black lives matter. That this is still the argument attests to a long history of black enslavement, lynching, disenfranchisement, and inadequate civil rights. Although it might seem like progress to observe the newfound ability of whites to perceive injustice to blacks in the form of lethal policing, it may also seem like the deepest rut imaginable: This rut—what I have elsewhere called the “melodrama of black and white”—still determines the basic terms of this argument.[1] It also shows the extent to which this archaic melodrama of racial good and evil still forms the framework for our national dilemma of race.

By melodrama, I mean, most simply, rhetorical-dramatic forms that strive to move audiences to pity the sufferings of the innocent. And in the strange alchemy of the melodramatic form, the more one suffers, the more one seems to acquire virtue. Contrary to received opinion, melodrama is not an archaic, badly acted excess of emotion. That is yesterday’s melodrama. Today’s melodrama, the one that galvanizes people to love a victim or to hate a villain, is playing out at this moment in the deaths of Michael Brown, Trayvon Martin, Freddie Gray, Eric Garner, Tamir Rice, Laquan McDonald, and others.

Gradually over time, the story changes: It is not just white people making the arguments. Black voices enter in, but what can be said in mainstream popular infotainment viewed by large numbers is determined by what has already been said. In this chapter, I examine the first two moves in this melodrama—to show how Uncle Tom’s Cabin was answered by The Birth of a Nation. Then I ask, through a look at Oscar Micheaux’s Within Our Gates (1919), how these two originally white-authored melodramas were answered by a black filmmaker.

Before Uncle Tom’s Cabin, the minstrel figure of fun was the dominant black stereotype. Except for an occasional Stephen Foster sad home song, the minstrel was not a figure to show much suffering. But when the minstrel home songs were appropriated by stage versions of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, the very question of what was the proper home for former slaves became a loaded one. Could the American home, the slave cabin, or the former slave cabin ever become the good home of melodrama?

The (Serial) Melodrama of Black and White

If Uncle Tom was the original black stereotype that black political consciousness resisted, he was also part of a much larger cycle of stereotypes originally forged in the white imagination. Eric Lott has shown that the original spirit of blackface minstrelsy—the imitation of what whites have stereotyped as black vernacular culture, especially black forms of song and dance—is at the very origin of American mass culture.[2] Given the abundant evidence of this contradictory “love and theft” of black culture by whites, it may not be surprising that the claim that black lives matter has had to operate in the face of a whole repertoire of demeaning stereotypes, which either implicitly or overtly argue that they do not.

However, as our contemporary real-life news reports return repeatedly to ever-new versions of the moral power of the Tom beating scenario, the elimination of stereotypes may not be the solution to the denigration of black lives. For the Tom story was the first influential claim in American mass culture that black lives do matter; only later was Tom’s stereotype despised. The answer to stereotypes has never been truer, more “authentic” depictions, free of stereotypes, but anti-stereotypes that are, of course, stereotypes themselves.

Tom himself grew out of the combination of two conflicting stereotypes of the white supremacist imagination: an older strain of minstrelsy, which, in addition to the burlesque antics of “minstrel fun,” cultivated the tradition of sad “home songs” in which otherwise happy-go-lucky slaves would long for a lost home figured as the “old plantation.” This plantation home was always a troubled site of virtue, but upon it Harriet Beecher Stowe erected the narrative of Uncle Tom’s Cabin about one slave (Tom), who stays loyal to his master, and another (Eliza), who flees north to Canada and freedom. If the stereotype of the Uncle Tom was what seemed to need overthrowing by the black racial imaginary in the 1950s and 1960s, the stereotype of the Uncle Tom in its own day was what melodramatically demonstrated the humanity of slaves in the first place.

I begin with the assumption that there is little use in isolating one particular stereotype—for either approbation or denigration—without considering the full context of its serial evolution. By serial evolution, I mean the way one kind of stereotype emerges connected to a particular narrative—say, the black man as the quintessential Christian martyr—and then gets reversed in a new kind of melodrama in which black and white, good and evil invert. This is what The Birth of a Nation did. It turned the black victims into villains and the white villains into racially beset white men desperate to protect “their” women from a paranoid vision of black threat. Serials repeat, but repetition is never exactly the same. The melodrama of black and white is remarkably repetitive even as its moral valences careen from good to evil in radical reversals.

In Playing the Race Card (2001), I traced some of the more important aspects of the melodrama of black and white across American culture from Uncle Tom to O. J. Simpson, from novel to theater to film and television through the popular consumption of race trials such as the police beating of Rodney King and the O. J. Simpson murder trial.[3] “Melodrama of black and white” is the phrase I used to describe the reversals of stereotype from victim to villain that have taken place throughout American history. D. W. Griffith’s racist masterpiece is the key moment when the original Tom melodrama turned into a serial through the insidious process of reversal that has made this ongoing story the longest-playing melodrama in US history.

Thomas Dixon was a Southern white supremacist who consciously reversed the moral poles of the Tom stereotype of black humanity of the antebellum era. Through the lens of the white supremacist view of Reconstruction, he reversed the moral and racial valence of the Tom stereotype while keeping the black/white antimony of racial melodrama intact. His first novel, The Leopard’s Spots (1903) begins what has been called his Reconstruction trilogy, but which might also be called, after Leslie Fiedler’s (1979) still-useful term, his anti-Tom trilogy (fig. 6.1). In part, it is a sequel to Uncle Tom’s Cabin, showing the disastrous results of the freeing of slaves in the South. It chronicles the further adventures of Simon Legree, the original villain of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, and the mulatto couple George and Eliza and their son, Harry, the original victims. When a grown-up post–Civil War Harry seeks to marry into a white New England family, the racism of would-be liberals is exposed as they “naturally” reject miscegenation. Such was the origin of what would become, in Griffith, Silas Lynch’s proposal to marry Elsie Stoneman. Dixon’s second novel, The Clansman: A Historical Romance of the Ku Klux Klan (1905), is less explicitly aimed at showing the disastrous outcome of Stowe’s story (fig. 6.2). Here, Dixon hones the material of the previous novel into a more focused melodrama of action that became the stage play The Clansman and the basis for Griffith’s film.

Dixon’s novels and plays were mostly popular in the South. They did not succeed in generating a new national racial antipathy toward blacks. But Griffith’s film based on Dixon’s first two novels did. And this new racial feeling, this new turn of the screw in the ongoing serial melodrama of black and white, was inextricably linked to the new power and epic sweep of the medium of cinema. Griffith thus succeeded in creating the white supremacist classic of which Dixon had only dreamed. And the reason for this, paradoxically, is that, unlike Dixon’s work, The Birth of a Nation did not seem to be the antagonist of Stowe’s Tom melodrama but rather its inheritor.

The probably apocryphal story of Thomas Dixon renaming Griffith’s film from his own title, The Clansman, to The Birth of a Nation, upon seeing its New York preview, nevertheless suggests his recognition that Griffith’s film, unlike his own works, had broken through to speak to a national, not just a sectional, audience (fig. 6.3). Though Dixon promulgated the idea of national rebirth forged through the hatred and expulsion of racial scapegoats, it was Griffith’s film that actually achieved this new national feeling by seeming to be democratic and fair. This, I think, is the real trick of each new incarnation of the Tom/anti-Tom material—it not only reverses but injects each new serial instance with new qualities borrowed from previous instantiations.

Here we encounter the nature of a mass media seriality that seeks not originality but repetition, though always repetition with a difference. Dixon recycled characters from Uncle Tom’s Cabin to exploit their popularity but also to détourné the original political impact of interracial amity into interracial hatred. He was also exploiting the popularity of the melodramatic family saga, only this time making whites the central characters in a later era of Reconstruction. Essentially, Dixon tried to repeat Uncle Tom’s Cabin with its feelings of interracial amity inverted to race hatred. To the usual serial dialectic of repetitive schema and innovation, he added the negative dialectic of a (good, Christian) Tom turned into his evil, bestial opposite.

Try as he might, however, Dixon failed to galvanize national racial feelings. One reason for this failure lies in the fact that Dixon’s starting point had been a vehement opposition to the sympathetic racial sentiments of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, which had especially moved Northern readers to weep for the sufferings of Uncle Tom at the hands of his cruel white masters. Griffith’s starting point, in contrast, was to incorporate both Stowe’s antebellum story and Dixon’s story of Reconstruction, thus not seeming to overtly spread hatred of blacks. This was his terrible genius.

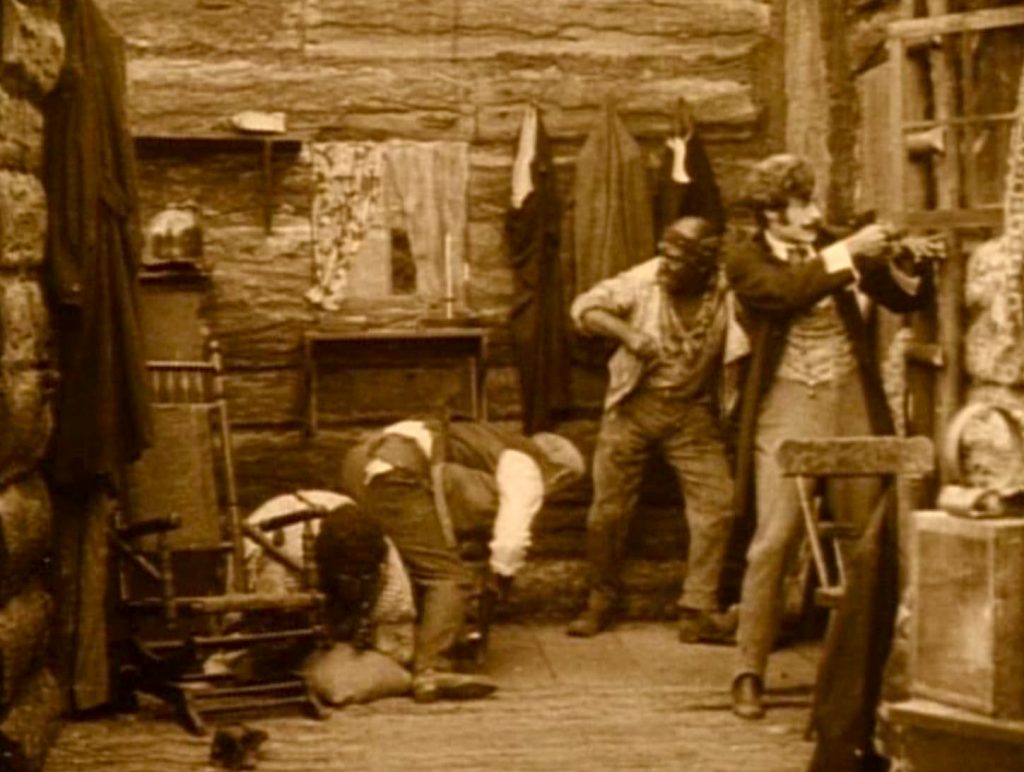

Dixon himself had refused to tell “the story of slavery,” not wanting to become an apologist for an institution that, in his eyes, had so disastrously brought the villainous “black seed” to American shores. Griffith might seem to follow Dixon’s sentiment toward slavery when, at the beginning of his film, an intertitle informs viewers that “The bringing of the African to America planted the first seed of disunion”—thus blaming disunion on both the Africans and on the slave traders that brought them (fig. 6.4). However, Griffith’s willingness to present a happy plantation version of the story of slavery in the first half of his film (the part that most critics have praised) borrows much from the beginning of Stowe’s narrative of good masters and happy slaves—the part before Tom is “sold down river”—and enables Griffith to repurpose much of the “romantic racialism” of the Tom story. In this way, Griffith does not fully invert the Tom story but instead adapts elements of its apparent democratic inclusion.

For example, the presence of the “faithful souls,” Mammy and Jake, in Griffith’s story, modeled on Tom and Chloe in Uncle Tom’s Cabin, offers Tom-like elements of racial sympathy toward the “good,” “faithful souls” that allowed The Birth of a Nation to become an agent of national (white supremacist) reunion under seemingly democratic, but actually exclusionary, auspices (fig. 6.5). It did this by offering whites in the North and South what felt like a fitting conclusion and answer to the sectional disunions originally sparked by Stowe’s version of the melodrama of black and white.

In The Birth of a Nation, the extreme pathos of the defeat of the South, which Dixon did not represent, resonates powerfully against the extreme action of the climax, in which the Klan rescues first Elsie, who is caught in the clutches of the mulatto Silas Lynch (fig. 6.6), and then an entire interracial group (fig. 6.7) surrounded in the cabin and fighting off “black hordes.” In these two action climaxes, Griffith, unlike Dixon, sets up two sites in need of rescue. The second of these is something Dixon could not have countenanced. Michael Rogin has argued that this rescue of the family from the cabin is not just from any cabin, but from a “Lincoln log cabin,” whose refuge ironically democratizes and merges, as the film’s most egregious intertitle puts it, “former enemies of North and South . . . reunited again in common defense of their Aryan birthright.”[4] But what Rogin did not note and what is visually apparent but not spoken in the intertitle is that former master and slaves are also united not in defense of an Aryan birthright but in defense of the cabin. This cabin wraps the former slave owners in the mantle of humble beginnings associated with the likes of Lincoln. Although it is technically the Southern “former master,” Doctor Cameron, who is rescued from the cabin and who rubs elbows with the humble Union veterans frying bacon over their hearth, he is here disassociated from the once-grand Cameron Hall plantation and the institution of slavery.[5] Griffith, unlike Dixon, thus makes his audience feel Stowe-like emotions of democratic inclusion and brotherhood even while rooting for the “common” defense of their “Aryan birthright.”

But perhaps the real reason Griffith can get away with such contradictory gestures of white supremacy and democracy is that the icon of the cabin goes well beyond the democratic associations with Abraham Lincoln (fig. 6.8). I have argued that nostalgia for a democratic and humble “home space of innocence” central to the felt virtue of so much melodrama, and so central to Stowe’s melodrama, was located in the icon of Tom’s cabin—the integrated place where Master George Shelby Jr. once taught Tom how to read, where Mrs. Shelby came to weep with Tom and Chloe, and about which the songs “Old Folks at Home” and “My Old Kentucky Home” are performed in many Tom plays.[6] This cabin seems to function out of proportion to its actual importance as a locale in Stowe’s novel and in the many “Tom Shows” that paraded model cabins through towns to attract audiences. It hovers over all Tom’s longing for his always problematic good, lost Kentucky home. As the American locus classicus of honest and humble beginnings, the cabin in Griffith’s film now becomes as important a place of virtue for the former masters as it once had been for the Tom slave.

By “integrating” the cabin with the Tom figures of Mammy and Jake and with the humble Northern Union veterans, Phil Stoneman, son of the radical Republican, as well as with the former members of the slavocracy, Griffith repurposed the previously dominant version of the melodrama of black and white and its “home space of innocence” to representative members of the whole nation. In a move of apparent democratic inclusion, Mammy and Jake willingly roll up their sleeves to join the whites to fight off the black marauders. When the group runs out of ammunition, Mammy clubs intruding black heads. Henceforth, all future film Mammies, such as the one in Gone with the Wind (dir. Victor Fleming, 1939), would devote themselves fiercely to the well-being of their white masters as if slavery had never ended. Thus, while Griffith freely includes Mammy and Jake as part of the good folks in need of rescue by the Klan, this very inclusion enables our not quite noting her later exclusion from the reborn nation.

Dixon had been consistent in his exclusion of blacks from any nostalgic image of the past or any happy ending pointing to the future. Griffith, however, freely borrowed the nostalgic musical associations with black culture that Dixon had so vehemently eschewed. Dixon even had Elsie give up the banjo and all “vulgar” Negro associations. With the melos of this older Tom melodrama insinuating the racial feelings of minstrelsy, Griffith’s eventual exclusion of blacks thus seems less a calculated policy of contemporary Jim Crow politics than a “natural” love of black culture consistent with the dominant culture of minstrelsy. It also seemed an equally “natural” exclusion of blackness when it does not behave so lovably. In the rescues carried out in the last third of the film, black men are quite literally wiped from the screen by what poet Vachel Lindsay once tellingly called a white “Anglo-Saxon Niagara.”[7] Indeed, the ride of the Klan is repeatedly figured as a flushing out of black chaos and violence as dark frames are suddenly flooded with white (fig. 6.9). A culminating shot effectively “parades” the racial cleansing that the multiple rescues have accomplished as the “Parade of the Clansmen” (fig. 6.10). Not surprisingly, neither Mammy nor Jake—nor any other “faithful souls”—are anywhere to be seen.

Moreover, whereas Dixon gives secondhand accounts of sexual attacks by black men on white women, even in his play The Clansman, Griffith much more luridly enacts them, even if censors forced him to change Gus’s overture to the little sister to a proposal of marriage (fig. 6.11). In the attack on Elsie Stoneman, Lynch’s handling of Elsie in lascivious ways that Dixon never dared portray is not only more lurid, but it seems as if the ride of the Klan is activated by this miscegenous sexual assault on a white woman. And in the cabin itself, that rape of the white women is the real threat is made clear by the way the white men prepare to kill the women lest they meet the “fate worse than death.”

It is thus in Griffith’s film that we first discover how a bad-faith white version of the melodrama of black and white came to believe in its own melodramatic virtue by appropriating the mantle of the good, humble cabin. By 1915, with The Birth of a Nation, three variations of a new, anti-Tom, stereotype had emerged—all of which sexualized warnings of the dangers of a racial amalgamation that had already been accomplished through the exercise of the droit de seigneur of former masters: Silas Lynch, the mulatto who lusts after Elsie Stoneman; Lydia Brown, the mulatta who holds sexual sway over Austin Stoneman; and Gus, the renegade Union soldier who lusts after the “little Sister.” All three refuted the humanity of the Christian slave.

The moral binaries of the melodramatic form proved their power in a new medium that seemed more modern and “realistic” than the older media of, first, novels and then plays. Cinema consolidated the very modernity of melodrama, making it relevant to a new age of national, not just sectional, union. With Griffith’s “answer” to Uncle Tom’s Cabin, a singularly popular melodrama of black and white became a serial phenomenon, asserting diametrically opposed forms of racial injury. Henceforth, in life or in fiction, no form of injury could seem innocent of racial motivation if blacks and whites were involved.

Black Reactions to The Birth of a Nation

The melodrama of black and white continued full speed ahead in mainstream American culture. Having leaped from novel and stage to silent film to sound film to television and, most importantly, into a twenty-four-hour news cycle and an internet-driven new media often fueled by citizen cell phones, it reaches into our contemporary moment. In this moment, it might seem that something like the perception of Tom suffering holds sway but perhaps only until the next O. J. Simpson comes along.

And finally, of course, blacks themselves would begin to enter into the discourse of this American melodrama of black and white, though in ways that were often predetermined by the fact that they were not in on it at the beginning. By definition, these were reactions that came from outside the mainstream. Melvyn Stokes has shown that, by far, the most prevalent reaction among blacks to The Birth of a Nation was that of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, in which whites and blacks worked together tirelessly either to ban or at least cut some of the more egregious scenes from the film. Epic court battles ensued from city to city, with little success early in the film’s run and more success after World War I, when the argument could be made that the film harmed the war effort and incited race hatred at a time when the nation needed unity.[8] The coincidence of the Supreme Court Mutual decision (in Mutual Film Corp. v. Industrial Commission of Ohio), which declared film not to be a form of speech and thus not entitled to protection, three days after the first Washington screening of the film meant that all film was vulnerable to censorship, not just Griffith’s. The NAACP treated each minor censorship of the film as a victory, but it is important to recognize that the arguments for censorship were the same arguments that would later be deployed against black films that tried to answer Griffith.

Another reaction to the film, and one that I find especially eloquent, testifies to the extreme anger and frustration felt by black audiences who saw the film. In Kevin Brownlow and Brendon Gill’s 1993 documentary D. W. Griffith: Father of Film, William Walker, now an elderly black man who saw the film in a colored theater in 1916, recalls, “Some people were crying. You could hear people saying God . . . You had the worse feeling in the world. You just felt like you were not counted. You were out of existence.”[9] Walker does not explain how the film accomplished his sense of eradication, of being “out of existence,” but I would submit that it had much to do with the way the film itself makes black people just disappear, as described above. Indeed, Walker’s frustration is palpable as he extends the logic of his own violent sense of having been rendered invisible onto a now thoroughly white supremacist world: “I just felt like . . . I wished somebody could not see me so I could kill them. I just felt like killing all the white people in the world.” Perhaps because he realized how much the race hatred of the film had already made his humanity invisible, Walker wished to use it as an advantage to return the violence he had experienced. Walker was caught up in the melodrama of black and white in a way that only allowed him the alternative of becoming the anti-Tom himself—the “black image in the white mind,” as George Frederickson once put it.[10]

But William Walker’s impotent despair at being counted out of existence and his desire to kill white people may have been something more than the anti-anti-Tom move that perpetuates the cycle of violence. It reacts not only to violence against blacks—Brownlow and Gill’s film shows the depositing of Gus’s lifeless body on the steps of the statehouse by the Klan as Walker speaks—but also to the powerful cinematic rhetoric that makes this interracial violence seem so natural and necessary. For what was also being counted out of existence was the future of African American representation in any but the roles of “faithful souls” for the next fifty years of mainstream film. Black autonomy and will, black sexuality in anything but its most threatening forms, black families, miscegenation itself—all these topics that are so central to black lives were being “counted out of existence” in American life and mainstream cinema. By the time the production code was in force, these topics, which Griffith had broached in the most negative, anti-Tom ways, would be taboo to both black and white filmmakers. Perhaps Walker’s deepest despair lay in an understanding of how the Tom scenario had been hijacked to create a bogus feeling of interracial amity only for those former slaves who were no longer “uppity” and did not seek to vote.

Within Our Gates, Oscar Micheaux’s 1919 filmic response to The Birth of a Nation, is the one film that best answers William Walker’s despair (fig. 6.12). It has, deservedly, received a great deal of scrutiny from film scholars, especially in Jane Gaines’s Fire and Desire: Mixed Race Movies in the Silent Era and, more recently, in Cedric Robinson’s Forgeries of Memory and Meaning: Blacks and the Regimes of Race in American Theater and Film before World War II.[11] I will not try here to fathom the great mystery and challenge of Micheaux’s fascinating body of work, or even the full importance of this one film. But I would like to place Within Our Gates in the context of the American melodrama of black and white that I have been describing. For what is important about Micheaux is how he navigates, without ever being able to negate, the dominant features of this serial melodrama. I thus argue, contra Cedric Robinson, that in this film, Micheaux does not disdain, subvert, or shatter the form of melodrama—all terms used by Robinson—but constructs his own melodrama of black and white in a fashion that might have assured a William Walker—had he been fortunate enough to see the film—that he was not “counted out of existence” and need not have recourse to a suicidal race war.

This is not to say that Micheaux’s film had any immediate influence in the ongoing evolution of this serial melodrama. Though it is the “black answer” to The Birth of a Nation in its time, it was seen by very few and soon disappeared for over half a century. There is thus no sense in which this work—which was censored in its day for some of the same reasons that The Birth of a Nation was censored, and, most importantly, for its treatment of miscegenation—could be said to have influenced national audiences. It may not even have influenced many black audiences for, as Jane Gaines notes, some of those black audiences joined with whites in protesting its incendiary depiction of the lynching of blacks. But at the same time, the film’s very existence attests to the creative power of a black sensibility that was acutely aware of the Scylla of the Tom route of sympathy for beset blacks and the anti-Tom Charybdis of violent race war.

Consider Oscar Micheaux’s narrative options in the wake of The Birth of a Nation: If Micheaux had simply been able to invert the moral and racial polarities of Griffith’s film, much as Griffith and Dixon had done to the Tom story, and if all other things had been equal, Micheaux might have told a story of an innocent black woman sexually threatened by a white man and, following the rescue model of The Birth of a Nation, depicted black heroes riding, running, or driving to her rescue and thus punishing the lascivious white aggressor. This would have been an immensely satisfying outcome for a William Walker. And if the story, like The Birth of a Nation, had been set in the era of slavery and then Reconstruction, it would have given him the added opportunity for revenge. It would also have set the historical record straight as to who was responsible for the very creation of the mulatto villains so prominent in The Birth of a Nation. But, of course, all other things were not equal; Micheaux could not tell such a story unless he created an outright fantasy, as in 1970s blaxploitation, or the contemporary counterfactuals of Quentin Tarantino, as in Django Unchained (2012). Historically, black heroes would have been singularly unable to rescue black women from the lust of white masters and overseers—not during slavery, not during Reconstruction, and not in the so-called Progressive Era of Griffith’s film. To simply reverse the Griffith/Dixon anti-Tom inversion of the Tom narrative was not an option.

The option that Micheaux did follow was to revert to selective aspects of the Tom story, repurposed and updated to counter The Birth of a Nation. For example, he depicted the suffering of a whole black family and the female heroine modeled on Eliza, who, unlike Tom, escaped to freedom and self-improvement. An ad for Within Our Gates, undoubtedly written by Micheaux since he did all his own promotion, called it the “Most sensational Story on the Race Question Since Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” indicating a tacit awareness of the more recent “sensation” of The Birth of a Nation and indirectly promising to return to the Tom model of the melodrama offering sympathy for black suffering. At the same time, however, Micheaux, like Dixon, adjusts his story to a later time—in this case, the late Progressive Era—which allows him to engage with at least one of the pressing issues of concern to Americans in this period. For though African Americans, most of whom had no vote, were generally excluded from many of the reform issues of this period—including women’s suffrage, election reform, government reform, and philanthropy—Micheaux joins the spirit of the age by focusing his reform narrative on the one issue that did allow his updated Tom family to participate in the reformist spirit of the time: the pressing need for Negro education. Through this route, Micheaux shows how his race can also engage in the contemporary Progressive issues of the time. Thus, in the best tradition of the melodrama of black and white, Within Our Gates, like both the many stage and film versions of Uncle Tom and the unprecedentedly popular singular The Birth of a Nation, offers a crusade for the cause of black uplift, updates Stowe with more active black heroes, and answers Dixon and Griffith but with a sensational topper.

The story is this: Sylvia Landry is a light-skinned Negro woman living with her cousin, Alma, in a middle-class home in Boston after working as a schoolteacher in the South. Sylvia attracts suitors—one of whom, Larry, is a shifty relative of Alma and a thief. Sylvia awaits the arrival of the man to whom she is engaged, the hardworking and respectable Conrad. When Conrad returns from work in Brazil, he finds Sylvia in a compromisingly intimate meeting with an older white man. Insanely jealous, he begins to strangle Sylvia and then abruptly leaves. No explanation is forthcoming.

Sylvia returns to the South to teach. When the school lacks funds, she travels north to Boston again to seek help from philanthropists. While there, she is robbed but rescued by a black doctor (Dr. Vivian), who, like every other man in the film, is soon enamored of her. While resting on a park bench, Sylvia sees a white child in the trajectory of a speeding car. She saves the child but is hit herself. A stay in a hospital allows her to get to know the elderly woman philanthropist whose car hit her and to explain her need to fund her school. The philanthropist, Mrs. Elena Warwick, consults with an equally wealthy Southern woman to determine how to best help the school. The Southern woman opines that money for Negro education would be wasted and that she would be much better off giving just $100 to Old Ned the Preacher. A vignette shows us Old Ned—Micheaux’s first, but not last, portrait of a hypocritical black preacher—exhorting his Southern congregation to worry about heaven rather than education and weaseling money from them during the collection. This vignette further shows Ned toadying up to his presumed white “friends,” who only laugh at him and kick him in the behind. In an extraordinary moment that cannot strictly belong to this Southern woman’s portrait of Ned, we see him drop the minstrel mask to reflect on the race betrayal that has led him to such a humiliating pass. In this vignette, Micheaux shows that the Tom stereotype of the white man’s friend has now taken on a modern, race-betraying sense of the word.

As Mrs. Warwick weighs the prejudiced advice of her Southern friend against Sylvia’s appeals, fast cuts build suspense as various scenes from the past are repeated: Dr. Vivian recalls past tender moments with Sylvia and pines for her, the Southern woman repeats her racist diatribe, Mrs. Warwick considers her choice. At this point, the climax of the film appears to be the decision of the white philanthropist, who finally decides to give not $5,000 but $50,000 to the Southern school. Mission accomplished, Sylvia returns south to the school, leaving Dr. Vivian bereft.

At the point of this weakly happy end to a narrative of uplift, Micheaux ties up a loose end of the story: the mystery of Sylvia’s past and that compromising, intimate encounter with the white man that drove her fiancé away. Micheaux brings back a minor character—Larry, the thief—who has coincidentally taken his stolen goods to the South and hidden out near Sylvia’s school, where he threatens to reveal some scandalous fact (or lie) about her past if she does not collude with him. In a move that is typical of many Micheaux’s films that depict restless migrations from South to North and back again, Sylvia leaves the school and returns to the North again. In a coincidence typical of melodrama of this era, Larry’s further criminal adventures in Boston lead him back to Sylvia’s cousin, Alma, where he is fatally shot in a robbery and Dr. Vivian is called to tend to him. A repentant Alma, Sylvia’s jealous cousin, then explains to Dr. Vivian who that white man was. An intertitle introduces this section as “Sylvia’s Story.”

A flashback that occupies the last twenty minutes of the film allows Micheaux to counter the racist Southern woman’s story of black ignorance and explain Sylvia’s deeper reasons for her relentless crusade in the cause of black education and delivers his pointed, sensational rebuttal to Griffith and Dixon. It is a story of Sylvia’s family set in the past but after the time of the events recounted in both the Tom story and Dixon’s and Griffith’s anti-Tom. It is a Tom melodrama of black suffering at the hands of whites but emphasizing the female self-reliance of the Eliza part of that story—the mulatta who must fend for herself.

The flashback begins in a sharecroppers’ cabin at the moment that the “father” of the family, Jasper Landry, is about to pay his debt to the white landowner. He is able to pay an accurate sum because now his adopted daughter, Sylvia, is educated and can keep his books so Landry will no longer be swindled. Nevertheless, Gridlestone, the landowner, does try to swindle Landry, and a struggle ensues. Efram, a nosy black servant of Gridlestone—another toadying race betrayer—sees this struggle between Landry and Gridlestone but misses the moment when a white sharecropper who has also been swindled shoots Gridlestone through the window of his decayed mansion. Efram assumes Landry has committed the crime and informs the community of poor white sharecroppers, who then search for the Landry family to lynch them (fig. 6.13).

What follows is Micheaux’s great sensation scene: the lynching of the Landry family cross-cut with a sexual attack on Sylvia by the brother of the murdered landowner.[12] Like Uncle Tom’s Cabin and unlike The Birth of a Nation, there will only be one rescue in the nick of time. The black family—father, mother, and son Emil (who alone escapes)—informed on by Efram, are captured, beaten, lynched, and burned, giving Micheaux the opportunity to show a truer side of lynching than the Klan’s highly ritualized ceremony around the punishment of Gus. Without close-ups or grisly details, yet not avoiding the facts, Micheaux exposes the brutality and violence of the bloodthirsty white mob, composed of poor white men, women, and children, as the poor white resentment it is. Neither too particular about why or whom it lynches, this mob does nothing to ascertain the guilt of Sylvia’s father, simply taking Efram’s gossip for truth, and, when the Landrys first prove hard to find, they seize Efram himself as a handy “boy” to string up in the interim. Like the story of Old Ned, Micheaux again elaborates on the fate of the race betrayer (fig. 6.14).

As Jane Gaines notes, the film cuts from the attack on Sylvia five times to different stages of the lynching, including the fire that consumes the bodies of the victims.[13] If ever a black woman needed rescue, this scene (melo)dramatizes that need, though also the tenacity of Sylvia’s defense. But when Gridlestone pulls away her bodice to expose her chest, he suddenly recognizes a scar that identifies Sylvia as his own daughter (fig. 6.15). Horrified, Gridlestone ceases his attack and the film abruptly cuts back to Alma, who has been telling this story to Dr. Vivian. We now understand with whom Sylvia had had her mysterious liaison—not a white-haired lover but her own father who was almost her rapist. Although Micheaux is careful to tell us in an intertitle that Sylvia was his “legitimate daughter from marriage to a woman of her race—who was later adopted by the Landrys,” one can only wonder how legitimate a Southern white man’s marriage to a black woman ever could have been in this period. Indeed, the film may insist on Sylvia’s legitimacy a little too much. As Jane Gaines puts it, “The scene is symbolically charged as a reenactment of the White patriarch’s ravishment of Black womanhood, reminding viewers of all the clandestine, forced sexual acts that produced the mulatto population of the American South.”[14] In other words, the coincidence of this highly charged recognition scene with the lynching of Sylvia’s adopted family forces the white patriarch to face, if not his past crime, at least his present one.

Sylvia is thus rescued, to some degree, by her putative respectability as Gridlestone’s daughter: to rape her would be incest, and it would further sully both her and his “legitimacy.” Sylvia’s rescue in the nick of time by her white father’s conscience is yet another aspect of Micheaux’s redeployment of the Tom story. Like Uncle Tom’s Eliza, Sylvia must fend for herself in a masculine and white supremacist world that threatens her on all sides. Where Eliza, the escaped mulatta slave was threatened with recapture and separation from her child, Sylvia faces the lynching of her adopted family, rape by her own father, strangulation by a jealous fiancé, and extortion by Larry, the thief. Such is still the “helpless and unfriended” situation of the mulatta. Both Eliza and Sylvia are vulnerable beauties. But unlike the white heroines of Dixon’s and Griffith’s racial melodramas, they are strong and defiant; they do not throw themselves off cliffs to avoid fates worse than death, nor are they prone to fainting. And although Cedric Robinson argues that the attack on Sylvia echoes that of Lynch on Elsie in The Birth of a Nation, it is only in the fact of the attack and the white gown worn by both women, not in its form of enactment, for Sylvia’s struggle is long and hard. In the end, however, Sylvia, like Eliza (and like Elsie in The Birth of a Nation) can only be rescued by white men—the good abolitionist Quaker who pulls Eliza out of the Ohio River and the less-good but conscience-stricken white father who suddenly recognizes the vulnerable condition of the mulatta daughter whom he himself created.

However, as the film’s ending shows, the final union of Sylvia and Dr. Vivian, like the reunion of George and Eliza in Uncle Tom’s Cabin, cannot solve the ultimate problem of white hegemony. These unions cannot provide a happy ending the way the double union of Camerons and Stonemans does at the end of The Birth of a Nation. Nor, to his credit, does Micheaux pretend that it does. Instead, and quite appropriately for the basic serial argument that the American melodrama of black and white is, we discover the couple in the midst of an argument. Sylvia is depressed, where an ordinary white heroine would be happy. The prospects for the future of the race worry her. Dr. Vivian tries to reassure her, but it is clear that their union, which does not even permit itself the triumph of romantic love, cannot conquer all. Race hatred endures. Dr. Vivian asks Sylvia to forget the distant past and to think of more recent instances of black heroism in the Spanish-American War and the recent “Great War.” Finally, and even more ambivalently, he resorts to the claim that what sets African Americans apart from others who are also less-than-welcome in the United States is that, “We are not immigrants.” This is indeed not a happy ending.

Cedric Robinson argues that with this ending Micheaux returns to the hackneyed melodrama of the rest of the film, and that only in the lynching episode has he managed to subvert the typical melodrama of Griffith’s or even his own film. “Neither Griffith’s end or Micheaux’s can trump the enduring impact of the images of violence and hatred which preceded them. Bourgeois couplings are ‘fake’ resolutions, an escapist fantasy lacking even the imaginative power to will away the horrific sights and sounds emanating from a society engaged in racial conflict.”[15]

I understand Robinson’s desire to see Micheaux as having escaped the constraints of melodrama. Melodrama can only offer imperfect solutions to the problems of racial injustice. The putative moral empowerment it offers is only that of the injured person or race. As we have seen, the melodrama of black and white is as perfectly capable of depicting whites as suffering injury from blacks as it is the reverse. And what could be more melodramatic than this recognition by a white father of his black daughter through the scar that symbolizes all the racial injury suffered by her race? Robinson wants to see the lynching-rape sequence as anything but melodrama—“an extended jazz improvisation . . . effectively subverting and trivializing the melodrama,” revealing that “the principal forces acting on our characters are not love, or romance, or jealousy or even coincidence” but a “racial conspiracy enforced by spontaneous acts of violence.” But the “jazz improvisation” Micheaux offers—a quality that belongs more to the casual style of his storytelling throughout than to this sequence— is founded on the hand of black and white melodrama he has already been dealt. He cannot break free from the melodrama of racial injury.

Robinson argues that Micheaux unconvincingly imitates Griffith’s happy ending in the form of “bourgeois coupling.” I argue instead that Micheaux had no alternative but to answer Dixon and Griffith (who were themselves answering Stowe) within the framework of the racially motivated injuries of the melodrama of black and white. What is new in Micheaux is the yoking of a new melodrama of racial uplift to the old melodrama of racial injury and his willingness to show that injury in an almost incestuous context. Crucial to the theme of racial uplift is the idea that Dr. Vivian and Sylvia remain firmly implanted in the only home they have ever known, whether North or South. Unlike George and Eliza at the end of Uncle Tom’s Cabin (the novel), who, when they finally reach Canada, then seek a “Freedom in Africa”–an Africa that has never been their home—return to Africa is decidedly not their future. It is precisely Micheaux’s commitment to uplift as a proud American native, and not as a fugitive or immigrant that is key to his new iteration of the Tom story in response to Griffith. Micheaux’s melodrama makes its claim for the “home” that Tom himself never actually owned.

Oscar Micheaux’s audacious solution was thus to presume that the bogus home once indicated by the ur-sentimental racial melodrama of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, was, in fact, the true home of African Americans, who were not immigrants but, in the experience of most blacks living at his time, born in the United States. That this statement promotes blacks at the expense of more recent immigrants—Irish and Italians especially—is a form of nativism that seems inherent to the American melodrama of black and white, which seeks a virtue linked to a home(land).

To work within the melodramatic mode is thus not to sell out to white, bourgeois hegemony. It is to work with the plausible narrative means available at a given time. Melodrama is the form by which the powerless gain a certain, and entirely provisionary, righteousness; and it is not unusual for that righteousness to even become self-righteousness on either side of the racial divide. But as a form prone to serial repetition, new iterations of its basic scenario of suffering can enable new forms of action. This essay attempts to understand how a Tom-victim can be inverted into an anti-Tom villain and how one African American director tried to reclaim the Tom-function of racial injury.

We might think of it this way: If William Walker had seen Micheaux’s film, he might not have wished to become invisible in order to “kill all the white people in the world.” If race war is the alternative, then it is not surprising that melodramas of racial injury have held such pride of place. But it is also not surprising that melodramas of racial injury can never be resolved; they can only perpetrate further melodramas of racial injury. Oscar Micheaux’s may represent one of the more ingenious responses, but, as we know, the story continues.

Linda Williams is Professor Emeritus of Film and Media and Rhetoric at the University of California, Berkeley. She is author of Playing the Race Card: Melodramas of Black and White from Uncle Tom to O. J. Simpson and Screening Sex.

- In Playing the Race Card, I recount the high points of this melodrama from Uncle Tom’s Cabin through The Birth of a Nation, The Jazz Singer, and Gone with the Wind, to television in the form of the miniseries Roots, television news, and the mediated trials of the police in the Rodney King beating and the trial of O. J. Simpson. Linda Williams, Playing the Race Card: Melodramas of Black and White from Uncle Tom to O.J. Simpson (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2001). ↵

- Eric Lott, Love and Theft: Blackface Minstrelsy and the American Working Class (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993). ↵

- Williams, Playing the Race Card. ↵

- Michael Rogin, “‘The Sword Became a Flashing Vision’: D. W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation,” in “American Culture Between the Civil War and World War I,” special issue, Representations 9 (Winter 1985): 179. ↵

- Griffith could easily have had the doctor take refuge in his own home. In fact, during the first half of the film, he had done just that when he showed the Cameron parents and daughters besieged in the house while “black guerilla” troops raided the town. ↵

- Williams, Playing the Race Card, 2001. ↵

- Vachel Lindsay, The Art of the Moving Picture (New York: Macmillan, 1916), 47. ↵

- Melvyn Stokes, D. W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation: A History of “the Most Controversial Motion Picture of All Time” (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), 229–231. ↵

- D. W. Griffith: Father of Film, directed by Kevin Brownlow and David Gill (New York: Kino Lorber, 1993), DVD. ↵

- George Fredrickson, The Black Image in the White Mind: The Debate on Afro-AmericanCharacter and Destiny (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1987). ↵

- Jane Gaines, Fire and Desire: Mixed-Race Movies in the Silent Era (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001); Cedric Robinson, Forgeries of Memory and Meaning: Blacks and the Regimes of Race in American Theater and Film before World War II (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2007). ↵

- As Jane Gaines notes, Micheaux’s great stroke of genius is to cross-cut the lynching of the Landry family with the simultaneous sexual attack on Sylvia by Arnold Gridlestone, the brother of the murdered landowner. Gaines, “Fire and Desire: Race, Melodrama and Oscar Micheaux,” in Black American Cinema, ed. Manthia Diawara (New York: Routledge, 1992), 56. ↵

- Gaines, Fire and Desire, 57. ↵

- Gaines, “Fire and Desire,” 49–70, 56–57. ↵

- Robinson, Forgeries of Memory and Meaning, 260–261. ↵