Revisiting (As It Were) the “Negro Problem” in The Birth of a Nation

Looking Back and in the Present

Michael T. Martin

In the weeks following Barack Obama’s successful presidential run in 2008, there was much talk and fanfare in the media of a “postracial” America. That this claim was deeply problematic was apparent to anyone with even the most cursory understanding of US society, and its egregious absurdity stood in stark and violent relief during Obama’s presidency—and does so even more in the post-Obama era. In counterpoint to such an assertion of an inclusive and color-blind United States, consider that African Americans are routinely subject to intimidation, unprovoked violence, and even murder by law enforcement agencies across the country and are disproportionately victimized by the criminal justice system.[1] Consider, too, Donald Trump’s dog-whistle racist evocation of Mexicans as “wetbacks,” “rapists,” and “drug smugglers”—an arguably significant factor and ploy in his successful bid for the presidency—in addition to his widespread characterization of all Muslims as “terrorist sympathizers” along with the corresponding calls for a wholesale banning of Muslims from entering the country. Indeed, mimicking Richard Nixon’s 1968 “Southern Strategy,” Trump’s bigotry and racist vitriol appealed to and mobilized many white voters and, in no small measure, contributed to his election.

Far from having disappeared, then, it would seem that racism and xenophobia are given free rein to return to the very central mainstream of US political and social life.[2] Such current political developments amplify and legitimize stereotypical and demeaning depictions of African Americans in popular culture, circulate among the polity, and embody raced discourses and practices of foundational institutions that regulate society.[3] No less than it did in 1865, 1965, or 2005, race matters to economic and educational opportunity, wealth and income inequality, residential segregation, racial profiling, immigration, and particularly criminal justice and voter suppression as modes of disenfranchising African Americans and others of basic rights.[4]

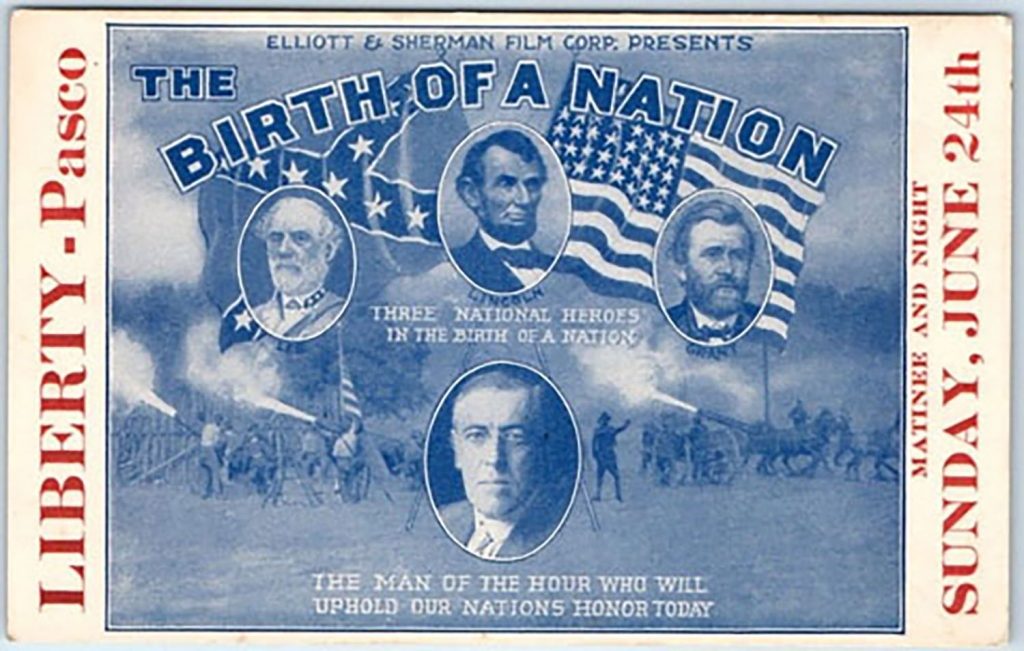

With the resurgence of popular mass protests in recent years against racial injustices and economic inequality—not least in the Black Lives Matter and Occupy movements—and growing challenges to reassertions of a white patriarchy demanding class obeisance and heteronormative conformity, I can’t think of a more timely film that conjoins the past in the present of raced denial and class divide than the photoplay The Birth of a Nation by D. W. Griffith.[5] Although lauded for its remarkable visual and narrative innovations and a box office hit with white film audiences, The Birth of a Nation is an unrivaled work of historical fiction and racial affront that, in defiling African Americans, provoked their indignation and protest when it was first screened in theaters in 1915.

No ordinary film for its time, consider film historian Melvyn Stokes’s estimation that The Birth of a Nation “changed the history of cinema”:

It was the first to be shown mainly in regular theaters . . . the first to be shown at the White House, the first to be projected for judges of the Supreme Court and members of Congress, the first to be viewed by countless millions of ordinary Americans. . . . In many ways, in fact, Birth of a Nation was the first “blockbuster”: It was the most profitable film of its time (and perhaps, adjusted for inflation, of all time), it helped open new markets (including South America) for American films, and it may eventually have been seen by world-wide audiences of up to 200,000,000.[6]

If place, time, and circumstance are consequential to a film’s reception and salience (as essays in this collection contend), then one account for The Birth of a Nation’s popularity at the time of its release and its ever-present controversy to this day is suggested by Davarian Baldwin, who described the film as “a cinematic history of its present: a tale of 1915 and the forces of urbanization, migration, and American empire that swirled around the early twentieth century.”[7] The period Baldwin refers to and that The Birth of a Nation gestures toward is marked by political upheaval and indeterminacy in both the United States and the wider world. Correspondingly, it was profoundly shaped by innovative artistic invention as new technologies and modes of communication evolved to blur the distinction between entertainment, information, and propaganda. To borrow from Michael Rogin, “The Birth of a Nation, by appropriating history, itself became a historical force.”[8]

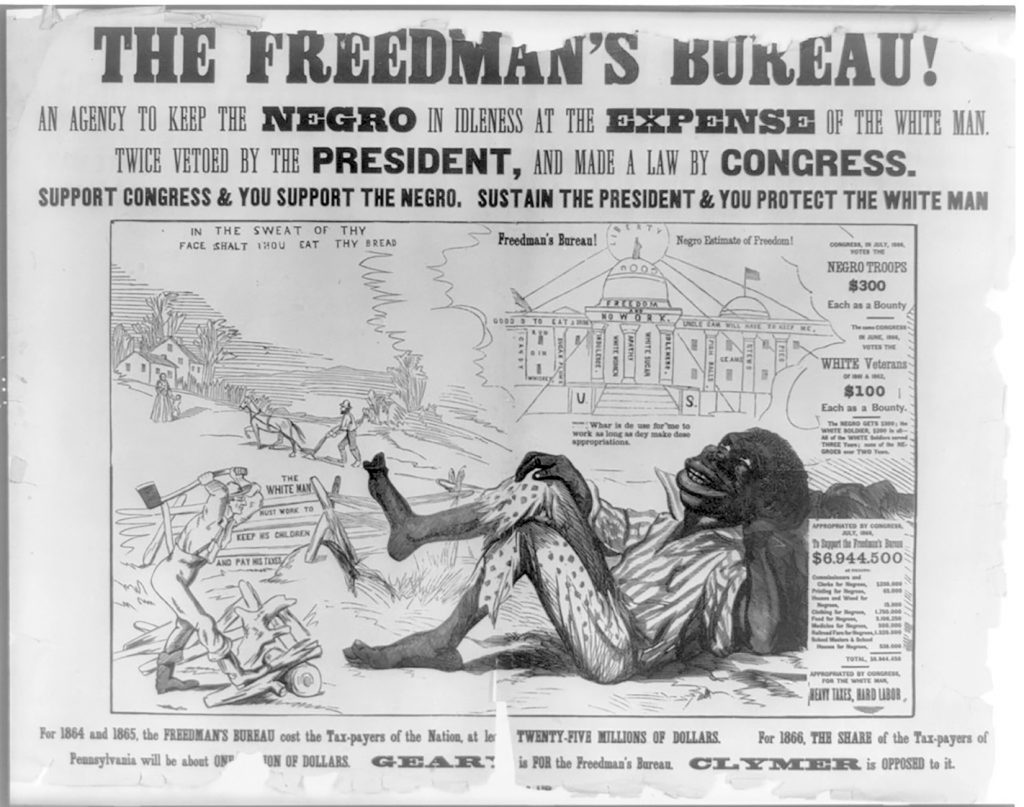

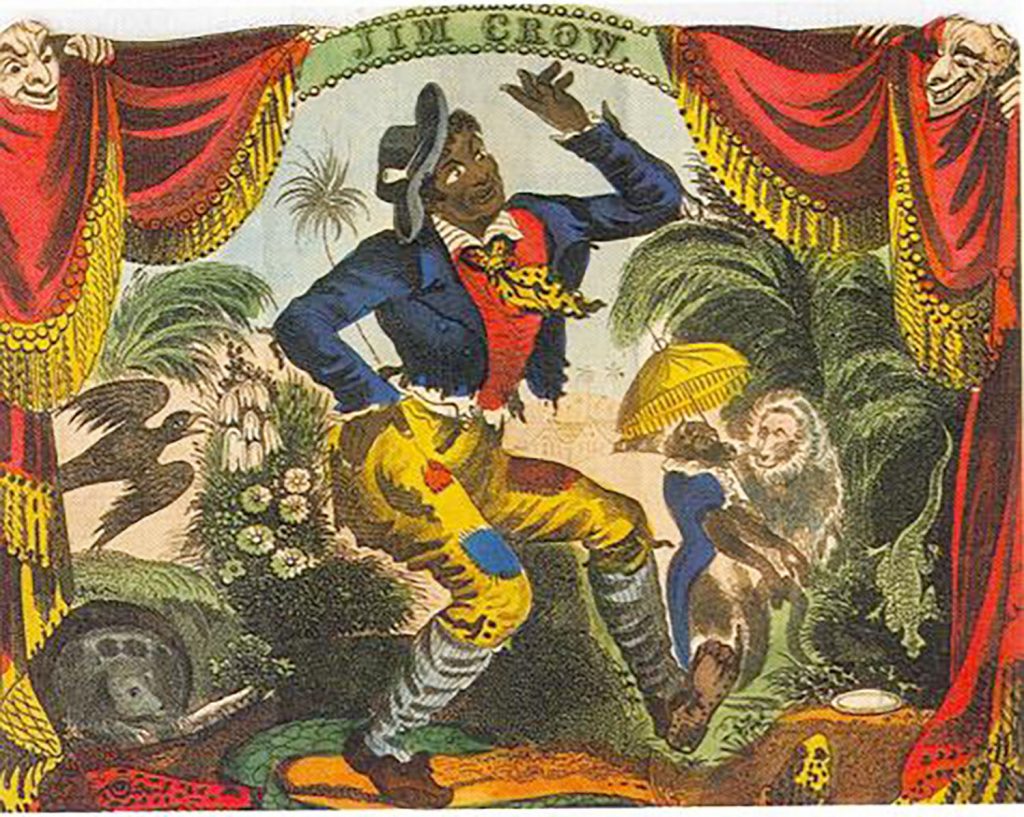

Moreover, and contrary to Enlightenment[9] precepts of reason from a century earlier and science in the conduct of Western civilization, this moment foregrounded elitist conceptions of human nature prefigured and informed by cultural precedents of racial disparagement expressed across the entire landscape of culture—from literature, popular lore, minstrelsy, and the ramblings and rants in newspapers and periodicals that constituted the general racialist discourses of the day to the widely accepted doctrine of scientific racism (figs. 0.1, 0.2, and 0.3).[10] These memorialized artifacts of popularized beliefs in the cultural marketplace of the early twentieth century framed debates about polygenetic notions of progress and posited the worldly order of things on biological, class, and cultural distinctions that endure to this day in the national psyche.[11]

During this period, the most egregious practices of Jim Crow happened, disenfranchising African Americans of their right to vote and other legalized exclusionary prohibitions; appropriating their labor (particularly in the South) under conditions of debt peonage; and practicing systemic violence as thousands of African Americans succumbed to public lynching (figs. 0.4 and 0.5). Such “racial terror” and “acts of torture,” intended to regulate the new order through intimidation, hastened their migration by the millions “from the South into urban ghettos in the North and West during the first half of the twentieth century.”[12]

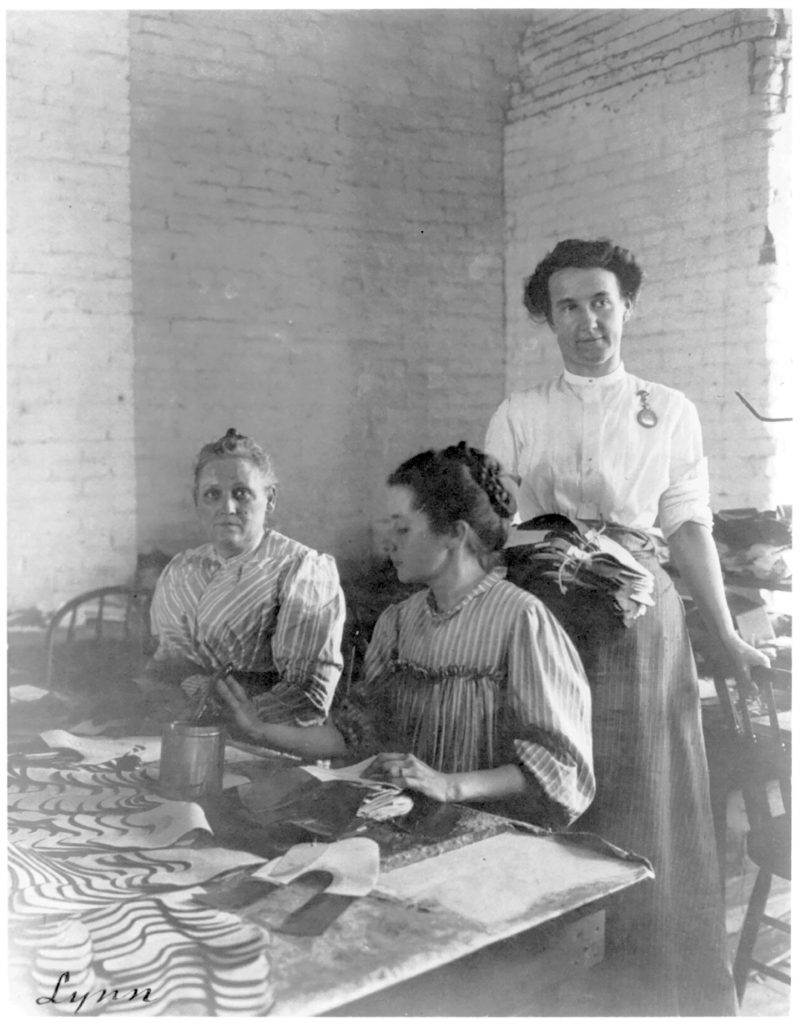

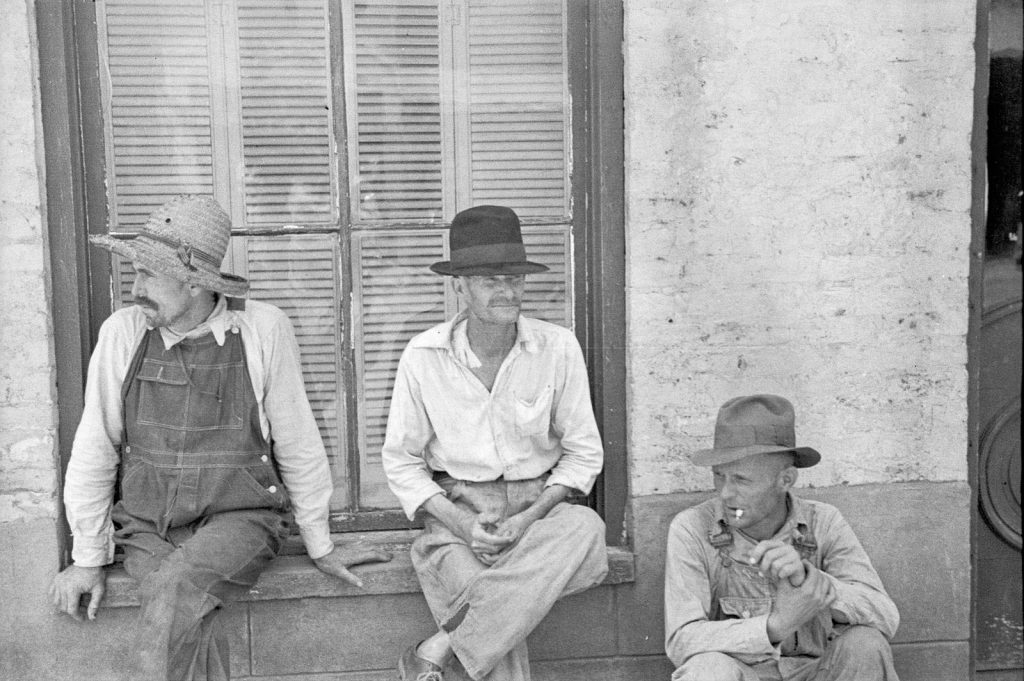

From the end of the Civil War to the early decades of the twentieth century, state power was aggressively and deliberately consolidated on behalf of white privilege. Native peoples of the continental United States had long been culled, warehoused on reservations, and even exterminated. Indigenous peoples of Puerto Rico, Haiti, Cuba, Hawaii, and the Philippines were variously subject to military conquest and territorial occupation as the United States established its nascent imperial dominance.[13] Immigrants from these colonies and migrants from Southern Europe converged on American shores in great numbers,[14] causing consternation and apprehension among (Anglo-Saxon) elites as they swelled the ranks of labor in the increasingly industrialized North and Midwest, beginning what would become a labor movement and struggle for workers’ rights against capitalism’s exploitive, dehumanizing, and often brutal practices.[15] Together, such claims in the wake of “manifest destiny” projected America’s outsized view of itself and its place in world affairs and, along with the denial of the franchise to African Americans, proffered a conception of the nation by racial lineage—and the social hierarchy that spawned it—sacrosanct and immutable. “For most of us, slavery is but a word, explained by other words, themselves barely understood: middle passage, chains, auction block. . . . The racial situation today is not much different from what it was when The House of Bondage was first published [1890]. Then, as now, the nation was in transition.”[16] And it is to the past in the present that this book revisits and remarks on The Birth of a Nation.

Like all forms of cultural production, film masks ideology while rendering it apparent. With cinema constituting a distinctive cultural form of modernity and particular mode of storytelling, The Birth of a Nation serves as Griffith’s filmic manifesto, an affirmative declaration of the legitimacy of white (read: Anglo-Saxon) rule through his vision of an America partitioned by race, gender, ethnicity, and class, poised for national greatness as it turned the corner and stumbled with great fanfare into the twentieth century. The Birth of a Nation’s importance is not only that it, as Stokes says, “changed the history of cinema” but also that it labors to naturalize a social order that masks the principles it claims to uphold: life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness—the sine qua non of US democracy.

Visually commanding, The Birth of a Nation reframes and conjures the way history itself and collective remembrance are read in the trauma and afterlife of slavery and, therefore, “is fundamentally a film about memory . . . that relies upon the nature and function of memory to perform its emotive and seductive work . . . to provide a shared, yet wholly personal experience of whiteness, one that would be immediately and intimately familiar and recognizable to its intended audience . . . to provide a collective memory, rooted not in nationality or region but in race.”[17]

A useful way of situating The Birth of a Nation in a regime of historical memory is to consider its location among four organizing classes of cine-memory that David C. Wall—a contributor to this collection—and I have developed in order to discern a film’s ideological significations and purpose. We contend that The Birth of a Nation exemplifies a type of Class I memory that works:

to affirm received assumptions and discourses about the past. It confirms the ideological certainties of the implied viewer, valorizes the beliefs, and conforms to the expectations of the audience. In doing so it functions to portray the hegemonic order as being a consequence of nature rather than one of culture. Yet the past it represents hides ideological assumptions and values that normalize the “reality” it claims to express. Events appear to be fixed in time, discrete, simplistically framed, and analytically wanting. Hollywood has pioneered this form of historical reconstruction [in The Birth of a Nation], de-historicizing events both in relation to the period in which they occurred and in relation to the present. Films of this ilk and their stock of memories attempt to bring closure to historical trauma. They are also committed to a wholly personalized vision of history, in which trajectories of class and race are elided through the personalization of cultural narratives within the individual [or family]. This removes the individual from the processes of history, thus making him/her entirely responsible for his/her personalized circumstances rather than the product or consequence of historical forces ranged both beyond and before the individual.[18]

With this concept of cine-memory in mind (and further discussed in Lawrence Howe’s chapter in this volume), it begs the following questions: In precisely whom did Griffith intend for The Birth of a Nation to provoke trauma? And who did he imagine would be demeaned and traumatized by the film?

Intuitively, we associate the aggrieved as African Americans, but I would argue that Griffith’s project was to traumatize and incite white audiences against blacks, whom he portrayed, with the exception of the “faithful souls,” as the purveyors of all things that threaten all manner of “whiteness” (figs. 0.6a and 0.6b). This is rendered apparent in scenes that legitimize the triumphant Ku Klux Klan as the only righteous and necessary means of self-defense against the barbarous blacks led by Silas Lynch—the mulatto—and his dream of a “black empire.” This terrifying prospect of black power was designed by Griffith to evoke such horror in the white imagination that it would be seen as a violation of God’s will and, for added measure, natural law. The Birth of a Nation’s call for justice and redemption serves, then, as a mediation for the trauma outside the film and in the actuality of raced experience (figs. 0.7 and 0.8).

Situating The Birth of a Nation within the genre of “trauma cinema” is appropriate, allowing as it does for the drawing of similar comparisons with the Western and war genres discussed in the chapters by Peter Davis and Alex Lichtenstein.[19] In The Birth of a Nation, the variant this form of trauma portrays is familial but signifying and emblematic of the nation and threat to whiteness rendered in the apocalyptic where power is inverted (“black empire”) and miscegenation licensed. Along this trajectory, The Birth of a Nation may be the first iteration of what we now refer to as trauma cinema—no less fantastical and dystopic than science fiction or horror movies are today, in which race (or its multiple symbolic embodiments) works as protagonist and/or subtext of the story.

Does The Birth of a Nation contribute to the intelligibility of the past or obfuscate it? Neither seen nor heard in the film (by design) are two historical factors in play that refute the veracity of its claims. The first factual omission relates to Davarian Baldwin’s earlier statement about The Birth of a Nation’s “cinematic history of its present” and reference to “American empire.” Unlike analysis of the exhibition and reception history of the film in the United States, The Birth of a Nation’s relationship to the broader contexts of US imperialism remains understudied. As the United States pursued imperial interests, the territories it obtained embodied distinctive cultural traditions and racial traits, and the population groups from these regions migrated, as noted earlier, mostly to urban sites, where African Americans increasingly settled. As their presence and numbers increased, thus threatening white (read: Anglo-Saxon) cultural sensibilities and the presumption of superiority, they contested institutions of rule. It was a circumstance not unlike today, when migrants traverse Central America at great peril to El Norte and thousands arrive at the southern shores of “Fortress Europe” to Greece, Spain, and Italy or by the inland routes from Eastern Europe to escape poverty, civil wars, and environmental degradation. As it does in the present, such migration—particularly for those population groups whose bloodlines were not of “Aryan” stock—invoked virulent nativist sentiments and prohibitions (figs. 0.9 and 0.10). In The Birth of a Nation, Griffith’s calculated schematic was to simplify race relations for white audiences to a black/white binary—a feature noted earlier of Class I cine-memory, which frames the social world as fixed in time and discrete. In this manner, The Birth of a Nation differentiates between black and foreign nationals, selectively inciting against the former to mitigate the combined threat of foreign nationals, who conceivably might discern similar class and economic interests and ally with them.

The second omission or misrepresentation of history concerns the disposition of wealth obtained by slavery. While The Birth of a Nation rejects slavery for the ills it brought upon the nation, it elides the matter of how the commerce in slave trading in the North and the labor it provisioned plantations with in the South generated great wealth on which both a planter aristocracy and industrial bourgeoisie arose and prospered and that enabled both shipping and banking sectors of the economy to become pillars of American capitalism. Why did Griffith mask such developments in his narrative of America’s renewal? It is fair to say that, along with the film’s racist and historical fictions, The Birth of a Nation elides the workings and contradictions of capitalism, thus naturalizing the social order and foundations on which its ruling class presumed privilege, dispensed power, and accumulated wealth. This, then, raises another critical question: Is The Birth of a Nation an untold story about class and class conflict, where race serves to divide and rule those who have similar economic and political interests (figs. 0.11 and 0.12)? And, subsequently, is the persistence of racism in the present, deeply ensconced as it is in US culture and institutions, a symptom and abiding consequence of capitalist relations of production?

An ever-vexing conundrum is the relational salience of social class and race in The Birth of a Nation. For political theorists and activists alike, debates about the determinations of class and race proliferate to this day, and particularly among Western Marxists. In this schema, race is subordinate to class divisions, as are ethnicity, gender, and religion. In cinema studies, however, conversations, let alone debates, about this relationship are curiously infrequent, analytically wanting, and woefully undertheorized.

Raced representations of class begin with the general premise that class correlates with economic factors. For Sean Griffin, “class is a term used to categorize people according to their economic status. It frequently involves a consideration of income level, type of profession, inherited wealth and family lineage and a diffusely understood idea of social standing.”[20] A defining construct in the organization of society, I understand class to be a formation whose temporality evokes distinctive iterations in cinema and the social world. However imprecise, representations of class illumine and prompt social consciousness, or obfuscate its historicity, as it regulates and legitimizes the order of things. In contrast to normative formulations, I propose a more expansive reading of class that engages with social theorist Pierre Bourdieu’s concept of habitus, in which patterns of behavior inscribed in the embodied common sense enable the social reproduction of status and standing.[21]

In certain genres of Hollywood fare, class is differently constituted for racial groups. For whites, representations align largely with economic factors; for blacks, they are, for the most part, constituted by noneconomic criteria. Traces of this racial bifurcation of class have precedence in Hollywood’s formation itself. Although portrayals of African Americans occurred as early as 1894 in such films as Lucy Daly’s Pickaninnies’ The Watermelon Contest (1896; 1900), Chicken Thieves (1897), Sambo and Aunt Jemima: Comedians (1900), and The ‘Gator and the Pickaninny (1900), the elaboration of a black social hierarchy was first masterfully rendered in The Birth of a Nation.[22] Like no other photoplay of its time, The Birth of a Nation codifies and elaborates with extraordinary specificity a racially inflected class formation. For whites, class was constituted by (cultural) pedigree and economic criteria without calling attention to itself and the inequality it sustains. Conversely, for blacks, Griffith fashioned something altogether different by aggregating black archetypes into a rudimentary social hierarchy constituted (a) by racial features, sexual exchange, and proximity to whiteness among the planter aristocracy and Northern elite and (b) by habitus, marked by dress codes, tastes, speech mode and intonation, and bodily gestures of persons who occupy a social space in a particular “field”—plantation South or industrial North. In this way, race operates as “cultural capital,” masking the determinations of economic factors.

The constituents of Griffith’s racial order (not to be confused with caste) comprise features of several archetypes. Consider the Cameron household domestics—the “faithful souls”—who display attributes of the Mammy and Uncle Tom; the Coon, lazy and dull-witted; Buck, sexually voracious; the “black beast,” who lusts after white women (and who, Linda Williams asserts in her chapter, was first evinced in The Birth of a Nation); and Jezebel, mixed-raced, amoral, and promiscuous. In the pecking order of things, light-complexioned male mulattoes are superordinate. Silas Lynch, opportunist and the alpha male groomed to be the leader of blacks, is accorded higher standing by his handlers, the Northern political class. But Lynch is also cast as the “black beast,” who covets the sexual favors of Stoneman’s daughter, Elsie, while he manically connives to create a “black empire” with her as queen consort (note the allusion to royalty, anathema to democracy, and the myth of a classless America).

Next in the lineup is that “deadly social virus,” the mulatta women who conspire with Lynch to advance their station by ingratiating themselves and exchanging sexual favors for the patronage of Northern carpetbaggers, whom Griffith would have us believe are sadly mistaken to uphold the newly obtained rights of former slaves. More generally, the mulattoes—both female and male—are distinguished from the dark-skinned blacks who labor in the fields and populate the bottom rung in the hierarchy and who, because of their mixed parentage, display intelligence and gesture—what we might think of as an example of Bourdieu’s cultural capital—in ways that mimic the white gentry. Self-serving, the mulattoes’ social standing is conferred by physical proximity to and association with whiteness. In Griffith’s characterization, they neither share an affinity nor identify with laboring blacks but use them instead as cannon fodder to advance their own interests. Curiously, the “faithful souls” constitute a distinct stratum in the slave regime, marked by their location in the master’s household; their status rests on an unflinching loyalty to the Cameron family and the patriarch’s goodwill and fortune, thus their identification with all things white (fig. 0.13).

In the larger frame of Griffith’s schema of race solidarity is the organizing principle for the nation’s renewal, trumping all other social divisions (including class and region). His genius was to elevate white supremacy to existential cause—immutable, insoluble, and permanent. In the drama of the historical epic that is The Birth of a Nation, Griffith rejects a class-based hierarchy while affirming patriarchy and the reign of the planter aristocracy in which everyone occupies their natural place and to which everyone is expected to adhere. Griffith accomplishes two devilish objectives that signify the ideological project of The Birth of a Nation: First, precipitated by the crisis of the Civil War and its aftermath, race is parsed to fashion a black social class, unlike that for whites and for which traces endure to this day in the cinematic. Second, America’s renewal pivots on white supremacy and patriarchy, despite momentary discord among fraternal relatives, because, for Griffith, the personal is inseparable from the familial, which is to say, the nation (fig. 0.14).

Praise for The Birth of a Nation and its popularity among white film audiences did not go unchallenged.[23] Indeed, when it was first shown in theaters and during the decades that followed, the film provoked protests as civil rights organizations and African American communities challenged derogatory depictions in the film and the received assumptions from which they are derived. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People mobilized to boycott and censor scenes that were particularly offensive to blacks (fig. 0.15); however, these efforts had limited success. William Monroe Trotter, the influential activist and editor of the Boston Guardian, who had earlier prevented the staging of Thomas Dixon’s novel The Clansman, labored through editorials, speeches, and rallies to mobilize against The Birth of a Nation’s exhibition in Boston.[24] And protests in the United States “spread to Canada, the [Panama] Canal Zone, and would even reach places like France,” contends film historian Cara Caddoo.[25] In her opening chapter in this collection, Caddoo chronicles the “mass black protest movement” against the film’s release and racist presumptions in 1915. Drawing from her earlier work, Envisioning Freedom: Cinema and the Building of Modern Black Life, in which she maps the initial and later protests to The Birth of a Nation, Caddoo asserts, “By 1917, the national movement had engaged hundreds of organizations across the country, involved tens of thousands of black protestors, and established demands for visual self-determination that endured well into the twenty-first century.”[26]

Although African Americans had been making movies since the earliest days of cinema, filmic opposition to The Birth of a Nation was first manifested in the ambitious but “disastrous” The Birth of a Race (1918). Plagued at the start by financial and production problems and, later, a compromised storyline, it was nevertheless, contends film historian Marc Ferro, the “first historical counter-film in American cinema in which African Americans incarnate a new vision of history.”[27] In the sphere of black filmmaking and outside Hollywood’s orbit, consider that, from 1909 to 1948, more than 150 independent companies made, distributed, and exhibited “race movies”—that distinctive aggregate of films crossing genres that oriented toward, and were shown in, segregated theaters and featured all-black casts. Such films engaged with the spectrum of black life and experience and comprised a range of visual and narrative styles and artisanal practices, all while anticipating and contributing to an African American cinematic tradition. Among the few successful companies in the “race film business” were the Lincoln Motion Picture Company, the Micheaux Film Corporation, and the Norman Manufacturing Company.[28]

Just as those early pioneering black filmmakers had to resist (implicitly and explicitly) the powerful violence to which The Birth of a Nation subjected black America, so, too, the film continues to work its violence in the current racial and political climate. And in that context and against the backdrop of extremist evangelical Christians, police violence, and myriad white supremacist terrorist organizations committed to keeping the United States as an Anglo-Saxon culture, it’s no wonder that The Birth of a Nation might resonate among a contemporary alt-right audience as it illumines the opposition against immigrants and black equality and civil rights. As a critical aperture to America’s past and a means to examine early cinema as technology, cultural form, and ideological apparatus and through its defamation of African Americans, The Birth of a Nation nods to and anticipates the present moment. And as Caddoo asserts, “In light of ongoing antiblack police violence, the continued exclusion of black Americans’ rights to public space, and the systemic valuation of private property over black lives, the history of The Birth of a Nation is just as much a story about our present as it is of our past.”[29]

Organized in three parts, this collection comprises original essays derived from the 2015 symposium and another by Lawrence Howe commissioned by the editor after the event. Three distinct organizing principles frame the chapters in the book:

- The Birth of a Nation as text, artifact, and cultural legacy

- The Birth of a Nation in historical time—then

- The Birth of a Nation in historical time—now

In developing their essays, contributors were asked to consider six research questions, particularly regarding the national and transnational contexts of The Birth of a Nation’s exhibition and reception histories as well as the intersectionality of race and patriarchy and their representations in popular culture.

- How does The Birth of a Nation contribute to the intelligibility of the past? For example, are enactments consequential to readings of historical claims?

- By what cultural and political means is The Birth of a Nation’s ideological mission refashioned and manifest in the present?

- For whom does The Birth of a Nation signify constructs of agency and mobilization (fig. 0.16)?

- Are there traces of The Birth of a Nation in contemporary Hollywood fare?

- Under hegemonic conditions, how is art repurposed and aesthetic strategies constituted in the service of politics?

- Is The Birth of a Nation relevant to understanding the present (fig. 0.17)?

Part I is devoted to a discussion of The Birth of a Nation in national and transnational contexts in historical time and contains five chapters situating the film’s reception in the United States and correspondence within the national politics where it was exhibited abroad.

Of The Birth of a Nation’s reception and exhibition in the United States, Caddoo’s and Andy Uhrich’s chapters provide critical insights and documentation. Caddoo asserts that African American women “were at the forefront of the protests” against the film and that working-class blacks supported protests precisely “because the movement encompassed many of their most urgent material, cultural, and political concerns.” In this important regard, her essay contributes to the literature of not only African American history but also social movements. She challenges ensconced views that “elites” within a subjugated class or social group rise to leadership rather than, in Gramscian terms, a bottom-up approach, where ordinary folk mobilize and draw leadership from among their own ranks. Such protests also illustrate a feature of some redress movements when the interests of aggrieved groups, seemingly discrete, galvanize and coalesce against commercial and institutional entities that are perceived as being aligned against them.

Uhrich’s chapter and novel contribution to the discussion, which is derived from dissertation research, engages with the presence and varied formats and iterations of The Birth of a Nation in white film collectors’ holdings and its screenings in “domestic and nontheatrical” venues such as schools, homes, and repertory theaters between the late 1930s and the late 1970s. Uhrich distinguishes between the multiple small gauge versions shown for the home market and the debates that ensued among collectors to rationalize such screenings. Purposefully narrow in scope and focus, Uhrich foregrounds the significance of this nontheatrical market of “specialized publics” to consider the “role of whiteness in film fandom” in the determination of American cinema classics. Ironically, his research reveals that at least one cultural black organization in 1971, the Grassroot Experience, reconstituted a screening of The Birth of a Nation accompanied by musical scores of the jazz greats John Coltrane and Pharaoh Sanders. Speculating on the motive for the film’s cultural appropriation and repurposing by blacks, Uhrich suggests that the “screening might have been intended as a sort of exorcism of the lasting, pernicious power of The Birth of a Nation or perhaps a clash between icons of black art and white cinema.” To document the different versions of The Birth of a Nation screened in nontheatrical venues, he examines David Bradley’s collection and discerns that, among the nearly 3,900 films Bradley had amassed, six were various versions of The Birth of a Nation. What this and Uhrich’s detailed chronology reveal of the film’s numerous iterations is “the range of companies and individuals that were distributing and exhibiting the film, and the transformations—textual, material, and paratextual—that the film underwent as it traveled the collector and nontheatrical circuits.” Uhrich’s examination of collectors’ views about The Birth of a Nation notes that some opinions were favorable and others were less so and critical, which raises anew the long-standing debate about the relationship of art and ideology, recalling one of the five research questions above: “Under hegemonic conditions, how is art repurposed and aesthetic strategies constituted in the service of politics?”

The Birth of a Nation’s exhibition and reception histories abroad varied, as the next three chapters address. Melvyn Stokes’s authoritative account of the film’s origins, production, exhibition, and reception makes for a compelling read. He discusses Griffith’s intent to extend The Birth of a Nation’s promotion in the United States to international markets and documents how the film was altered to appear less inflammatory to Canadian audiences, noting that the “entire so-called rape sequence . . . was required to be cut.” Stokes also notes that protest against The Birth of a Nation was “almost entirely black-led” in Canada. In Britain, and in contrast to Canada, Stokes claims that, with few exceptions, scholars agreed that the opposition to the film’s exhibition there was minimal. Conversely, in France, the film was denied a visa by the Central Commission of Control in 1917; it was screened seven years later in 1923 and, after four performances, was banned by the government largely because of objections by “influential black politicians in the National Assembly.” Further, a factor in The Birth of a Nation’s exhibition success abroad were “road shows” in Britain, South America (Argentina, Chile, Peru, Bolivia, Uruguay, and Brazil), Japan (though it was shortened to little more than half the length shown in the United States), and Australia and New Zealand. As in France, Germany the exhibition of The Birth of a Nation in Germany was delayed in the immediate aftermath of World War I because of the racialist international campaign “Black Horror on the Rhine,” against the presence of French African troops in the country. In South Africa, where the film was not shown until 1931, Stokes draws comparisons between The Birth of a Nation and De Voortrekkers (1916), describing their shared anxieties (“sexual paranoia”) and false claims to nationhood that blacks challenged.[30] Stokes concludes this exacting study noting omissions in The Birth of a Nation’s reception in those countries where it was exhibited in Latin America, Japan, Scandinavia, the Caribbean, and Britain’s African colonies, with the exception of South Africa.

Next, Peter Davis’s brief but informative chapter draws comparisons between The Birth of a Nation and South African productions De Voortrekkers (Winning a Nation, 1916) and They Built a Nation (1938).[31] He argues that the “assertion of white supremacy and black menace,” the projection of political power, and, more important, nationalism inscribed in these films share similarity with The Birth of a Nation. Although not shown in South Africa until 1931, the film, Davis contends, played an “indefinable role” in the formation of Afrikaner solidarity and national identity and that an earlier film by Griffith, The Zulu’s Heart (1908), “shows an awareness” by Griffith of the “parallel history with the United States,” evoking the travails of a pioneer family under seize by Indians in the American frontier. In They Built a Nation, Boer society is mythologized as genteel and stable, later reconciled between Afrikaner and Anglo, similar to Griffith’s portrayal at the end of The Birth of a Nation between Northern and Southern whites. In both films, Zulus and blacks are cast as aggressive and treacherous but, curiously, in They Built a Nation, not a sexual threat to white masculinity—unlike in The Birth of a Nation, where the sexual threat, arguably, works as the central organizing motif.

Alex Lichtenstein’s compelling chapter is comparative as it is synthetic, putting these contributors’ essays in productive conversation with one another. First, he notes that South Africa and the United States are settler societies obtained by conquest and occupation and that The Birth of a Nation is “a parable of settler colonialism” as, too, They Built a Nation is.[32] Together, the two films signify what Lichtenstein contends is a feature of settler societies, “the persistence of white nationalist mythology” manifest in the cinematic genre of the Western.[33] Second, he makes two critical claims that the films’ evocation of white nationalist mythology is repurposed, reenacted, and convened across place, circumstance, and time in racialized discourses of the nation. However racialist the films are, Lichtenstein calls for a more nuanced and complex reading of The Birth of a Nation and They Built a Nation, asserting that, above all, both films are “fundamentally nationalist in character.” In this claim, Lichtenstein nods to Davis and proffers an expanded reading of The Birth of a Nation as a war film while asserting black complicity in propagating received views about Reconstruction up to and during the 1950s, until the historiography of the period radically changed during and following the civil rights movement.

Part II contains two chapters that look beyond The Birth of a Nation’s formal innovations in visual storytelling to consider its rhetorical and representational strategies that signify the film’s ideological project. Several consequential subjects are addressed in Williams’s essay: African Americans’ response to the film, the importance of Oscar Micheaux’s reworking of melodrama in Within Our Gates (1919) to reinscribe African Americans in the narrative of America’s racial history, and the uneven and problematic black portrayals in some race movies before and after The Birth of a Nation in what she refers to as the “American melodrama of black and white.” But what stands out and is most compelling is Williams’s claim that, in The Birth of a Nation, Griffith introduced a novel stereotype of the “black marauders” to shift “racial sentiment away from the sufferings of Uncle Tom and toward the sufferings of an embattled White South.”[34] As such, and in consideration of the mobilizing activities of white supremacists at the time, the introduction of such a threatening—indeed, incendiary—stereotype in the narrative of race was most problematic for white film audiences because it provoked anxiety that miscegenation infers to this day.

In correspondence to Williams’s take on the “melodrama of black and white,” Howe’s chapter and close reading argues that The Birth of a Nation’s historicism works as a rhetorical strategy in and out of the frame to “couch the film’s racist polemics” as factual and, therefore, objective. Emphasizing Griffith’s use of historical enactments, Howe notes that such facsimiles project a seemingly credible authenticity for “the authority of history.” He observes three distinct forms of historical reconstruction in The Birth of a Nation: scenes of battle, “tableaux of momentous [defining] national events,” and a third form that is illustrated by the enactment of Lincoln’s assassination. The two essays in Part II reveal the means by which Griffith constituted and signified the ideological project of The Birth of a Nation: to direct blame for America’s social ills not on the social order that caused and sanctioned injustice and inequality but on the presence of blacks who dared challenge it.

Part III considers various cinematic iterations a century after The Birth of a Nation’s release and the film’s ideological aftereffects in the context of discourses that claim the United States as a postracial nation. Four of the five chapters in this section examine correspondences between more recent films and The Birth of a Nation, and the final chapter dismisses the film’s relevance in the present.

First in the lineup is Paula Massood’s chapter, which situates The Birth of a Nation in what Ed Guerrero has named the “plantation genre.” Focusing on Quentin Tarantino’s “cinematic style”[35] in the genre-bending Django Unchained (2012), she argues that the film, like the conventions of plantation literature, aligns more with than against aspects, for example, of interracial violence in The Birth of a Nation. Massood describes how the film anticipated the genre conventions of the Western, blaxploitation, and action movies, along with those of the plantation genre. Noting how both films deploy historical fiction, spectacle, and melodrama to portray the Ku Klux Klan as an “intimidating and invincible force,” Massood foregrounds the irony of their contradictory significations: in The Birth of a Nation, the Ku Klux Klan is portrayed as “heroic” and in Django Unchained as “an overwhelming and terrifying force.” Further, Massood delineates the symbolic purpose of lynching in both films to regulate racial and sexual divides, and she concludes—contrary to Tarantino’s claim that in Django Unchained is to be found a new genre—that the film constitutes a “generic mash up that lacks a cohesive identity.”

Next, Julia Lesage’s chapter puts Steve McQueen’s 12 Years a Slave (2013) in conversation with The Birth of a Nation. In the former, it is metonymy, whereas the latter evokes the rescue narrative by the Ku Klux Klan’s unfettered vigilantism as a “legitimate” mode of intervention for societal dysfunction in the wake of the Civil War. Lesage proffers a materialist reading of 12 Years a Slave as a “realist” narrative in counterpoint to a psychoanalytic one for The Birth of a Nation’s “melodramatic structure.” For example, in emphasizing the “Southern rape complex” as metaphor for a vanquished South, Lesage claims that The Birth of a Nation is a “projective fantasy” and likens the cabin scene to a “besieged vagina” rather than the site of a reconstituted (white) nation.[36] Unlike other interpretations of the cabin scene, Lesage advances a new reading that is novel and provocative by its sexual inference and associations. No less intriguing an analysis and particularly cogent is Lesage’s materialist approach to 12 Years a Slave. She deconstructs the director’s aesthetic strategies that gesture toward social space—a space where power relations are manifest and differentiated by gender, race, and class. In doing so, Lesage foregrounds an ethos of freedom where the protagonist, Solomon Northup, evinces in captivity agential authority to “develop both material and inner resources, act, plan, create values, choose many aspects of his daily routines, and forge short- and long-term goals” in such liminal spaces under conditions of bondage—marking the slave’s assertion “to maintain a sense of self.” Last, in the rich details of the analysis, Lesage points to 12 Years a Slave’s power of affect, showing “what slavery felt like.”

Anne-Marie Paquet-Deyris’s chapter discerns resonances between The Birth of a Nation and Spike Lee’s Bamboozled (2000) and Justin Simien’s Dear White People (2014). Like other contributors to this collection, she refutes the claims of a postracial America, asserting that both of the more recent films, unlike The Birth of a Nation, labor most directly to challenge normative accounts of America’s racial history. Contrary to Chuck Kleinhans’s assertion in the concluding chapter against The Birth of a Nation’s importance today, Paquet-Deyris contends that “the impact of The Birth of a Nation is still so strong that the film’s current reception summons very specific and passionate reactions about the staging of race and inequality today.” For comparisons with African Americans’ response to The Birth of a Nation, she notes similar reactions of French students to representations of Syrian and African migrants on French television. Regarding Dear White People, Paquet-Deyris argues that it serves as a counterpoint to The Birth of a Nation’s racial discourse by reclaiming black identity in the present and inverting the representation of whites along the lines of Griffith’s depictions of blacks. And for Bamboozled, she distinguishes Lee’s representational strategy to recycle “grotesquely stereotyped” black bodies to illustrate how racism operates in the present.

David Wall’s chapter and novel account of black masculinity in Etan Cohen’s interracial buddy film Get Hard (2015) reads a reconstitution of the deep sexual and racial anxieties that shape The Birth of a Nation so profoundly. Further, considering the relationship between a film’s formal structure and its ideological assertions, Wall draws on linguist Mikhail Bakhtin’s notion of the “dialogic,” by way of situating meaning making as a process that is to be constantly renegotiated in time and place and in relation to a viewer’s subject position. In a theorized and complex approach, Wall meticulously unravels the spatial matrix in which race and the black body are situated in each film to make sense of their shared meaning, however renegotiated and reconstituted. His reading of Get Hard demonstrates that the film “labors to convince viewers of its knowing postracial sensibility while mired in the trammeled racial representations it purports to undermine” and, in doing so, recalls The Birth of a Nation and the whiteness they share.

Last in the queue is the late Chuck Kleinhans’s provocative and partly autobiographical chapter. Contrary to the contributors before him, Kleinhans posits that The Birth of a Nation has neither meaningful importance today nor should it evoke or “deserve an angry response.” Indeed, he asserts the film is “laughable” and that it merits “ridicule.” First, he situates the fiftieth anniversary of The Birth of a Nation in the context of the mid-1960s—the era that spawned the formalization of film studies—arguing that “within cinema studies, this historical epic was canonized, often with praise that neglected the film’s racism, even during the civil rights era.”[37] Contending that The Birth of a Nation’s shelf life as propaganda has expired and is no longer effective for audiences today because “the film’s style and politics are outmoded” and “new forms of social media . . . uses snark and sarcasm to speak truth to power.”[38] Kleinhans counsels, “We don’t need to fear it” or let it evoke our anger, because the “best response [is] dismissive laughter.”

Notwithstanding its “overt politics” and simplistic assumptions on behalf of ideological aims, the efficacy of The Birth of a Nation in galvanizing hatred and prejudice is not lost to racists and nativists today as we turn another corner and find ourselves stumbling into the next century burdened by the same issues that inspired Griffith to realize The Birth of a Nation. It is with these developments in the present in mind that one hopes this collection has meaning and utility.

Michael T. Martin is Professor at The Media School, Indiana University, and Editor-in-Chief of Black Camera: An International Film Journal. He is editor with David C. Wall and Marilyn Yaquinto of Race and the Revolutionary Impulse in The Spook Who Sat by the Door.

- Ava DuVernay’s documentary 13th (2016) not only explains the multiple ways in which African Americans are unfairly targeted by the justice system because of their race but also makes a powerful argument for these processes as deliberate efforts to maintain disciplinary control over black bodies that was lost after the end of slavery. ↵

- See “The Trump Effect: Spreading Hate at School, at Church, and Across the Country,” Southern Poverty Law Center, February 16, 2017, http://www.alternet.org/right-wing/trump-effect-spreading-hate-school-church-and-across-country; and Steven Rosenfeld, “A United States of Hate Has Exploded under Trump,” Alternet, February 15, 2017, http://www.alternet.org/print/election-2016/united-states-hate-has-exploded-under-trump. Consider that the almost uniform conservative response to Obama was driven in no small measure by coded racial anxiety. Recall the campaigns of 2008 and 2012, in which race, citizenship, and nationality were strategically deployed to mobilize conservative white voters and discredit Obama’s eligibility to hold office. The “birther” stratagem was intended to discredit—indeed, invalidate—Obama’s eligibility for the presidency as an African and foreign national, foregrounding race and alien status. See Michael Eric Dyson, “Barack Obama, the President of Black America?” New York Times, June 24, 2016, https://www.nytimes.com/2016/06/26/opinion/sunday/barack-obama-the-president-of-black-america.html; Paul Mason, “Globalisation Is Dead, and White Supremacy Has Triumphed,” The Guardian, November 9, 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2016/nov/09/globalisation-dead-white-supremacy-trump-neoliberal; Andrew O’Hehir, “Trump, Sanders and Tribalism: Why the Donald’s Dark Allure Goes Deeper Than Racism and Xenophobia,” Alternet, September 13, 2015, http://www.alternet.org/print/election-2016/trump-sanders-and-tribalism-why-donalds-dark-allure-goes-deeper-racism-and-xenophobia; and Juan Cole, “Yes, Trump, Some Americans Also Murder: Some Are Your White Supremacists,” February 6, 2017, Reader Supported News, http://readersupportednews.org/opinion2/277-75/41804-yes-trump-some-americans-also-murder. ↵

- See Matthew Pratt Guterl, Seeing Race in Modern America (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2013). ↵

- Numerous studies substantiate such claims. See Michael K. Brown, Martin Carnoy, Elliott Currie, Troy Duster, David B. Oppenheimer, Marjorie M. Shultz, and David Wellman, “Race Preferences and Race Privileges,” in Redress for Historical Injustices in the United States, ed. Michael T. Martin and Marilyn Yaquinto (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2007), 55–90; and the more recent studies by Daria Roithmayre, Reproducing Racism: How Everyday Choices Lock in White Advantage (New York: New York University Press, 2014) and David Dante Troutt, The Price of Paradise: The Costs of Inequality and a Vision of a More Equitable America (New York: New York University Press, 2014). ↵

- The Birth of a Nation was adapted from the novel The Clansman by Thomas Dixon, which, as the film does, glorifies the Ku Klux Klan. The film was used to recruit for the Ku Klux Klan until the 1970s. Xan Brooks, “The Birth of a Nation: A Gripping Masterpiece . . . and a Stain on History,” The Guardian, July 29, 2013, http://www.theguardian.com/film/filmblog/2013/jul/29/birth-of-a-nation-dw-griffith-masterpiece. ↵

- Melvyn Stokes, D. W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007), 3. ↵

- Davarian L. Baldwin, “‘I Will Build a Black Empire’: The Birth of a Nation and the Specter of the New Negro,” Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era 14, no. 4 (2015): 599. ↵

- Michael Rogin, “’The Sword Became a Flashing Vision’: D. W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation,” Representations 9 (1985): 186. ↵

- Such Enlightenment tenets, however, excluded European imperialism and relations between the races in Africa, among other regions of the world inhabited by peoples of color. See Emmanuel Chukwudi Eze, ed., Race and the Enlightenment—A Reader (Cambridge, MA: Blackwell, 1977). ↵

- For example, see the Encyclopeadia Britannica’s 1895 entry, which contains several explicit references, such as the anatomical features of the “Negro” approximating that of the gorilla, “enabling the Negro to butt with the head and resist blows which would inevitably break any ordinary European’s skull.” The entry also describes “premature ossification of the skull, preventing further development of the brain, many pathologists have attributed the inherent mental inferiority of the blacks, an inferiority which is even more marked than their physical differences.” Encyclopaedia Britannica, American ed., vol. 17 (New York: Werner, 1895), 316–320. ↵

- See W. Fitzhugh Brundage, “Working in the ‘Kingdom of Culture’: African Americans and American Popular Culture, 1890–1930,” in Beyond Blackface, ed. W. Fitzhugh Brundage (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2011), 1–42. ↵

- Lynching, as a systemic practice, took place from the Civil War to World War II. See the Report Summary of Lynching in America: Confronting the Legacy of Racial Terror (Montgomery, AL: Equal Justice Initiative, 2015), 3. ↵

- In counterpoint to empire, recall the rise of antisystemic movements by workers, racial minorities, and women in the United States and, internationally, the Mexican and Russian revolutions in play, for example. ↵

- Consider that, while immigrants from Southern Europe were accepted, others were denied entry from Asia, marking the closure of America’s borders as anti-Asian sentiments and movements emerged, beginning as early as 1882. ↵

- Along with the racial terror in the South, the formation of the factory and mass production under industrial capitalism was also cause for why African Americans migrated North and to the Midwest at the turn of the century in pursuit of employment and opportunity. ↵

- Frances Smith Foster, introduction to The House of Bondage or Charlotte Brooks and Other Slaves, by Octavia V. Rogers Albert (New York: Oxford University Press, 1988), xxix. ↵

- Michael T. Martin and David C. Wall, “The Politics of Cine-memory: Signifying Slavery in the History Film,” in A Companion to the Historical Film, ed. Robert A. Rosenstone and Constantin Parvulescu (Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2013), 446–447. ↵

- Ibid., 448–449. ↵

- In Janet Walker’s study, the focus is on incest and the Holocaust. See Walker, Trauma Cinema (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005). ↵

- Sean Griffin, “Class,” in Schirmer Encycloypedia of Film, vol. 1, ed. Barry Keith Grant (New York: Thompson Gale, 2007), 303. ↵

- For Bourdieu these include social, cultural, and symbolic capital manifest in social relations. ↵

- For elaboration, see Anna Everett, Returning the Gaze: A Genealogy of Black Film Criticism, 1909–1949 (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2001), chap. 1. ↵

- See Stokes, D. W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation, chap. 6. ↵

- See Dick Lehr, The Birth of a Nation: How a Legendary Filmmaker and a Crusading Editor Reignited America’s Civil War (New York: PublicAffairs, 2014). For a comprehensive account of the film’s reception and opposition to it, see Stokes’s masterful work, D. W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation, chap. 6. ↵

- See Ashley Clark, “Deride the Lightning: Assessing The Birth of a Nation 100 Years On,” The Guardian, March 5, 2015, http://www.theguardian.com/film/2015/mar/05/birth-of-a-nation-100-year-anniversary-racism-cinema. A consideration of Caddoo’s important study is suggested for context of the African American response to The Birth of a Nation. See Cara Caddoo, Envisioning Freedom: Cinema and the Building of Modern Black Life (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2014), 140–162, 163–169. ↵

- See Caddo, Envisioning Freedom, 140. ↵

- Marc Ferro, Cinema and History (Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press, 1988), 152. Italics appear in the original. For the backstory, see Thomas Cripps, Slow Fade to Black (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993), 70–76. ↵

- See Barbara Tepa Lupack, foreword to Richard E. Norman and Race Filmmaking (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2014) ix–x. ↵

- See Cara Caddoo’s essay in this volume. See also Linda Williams’s essay in this collection for a discussion of how race films resisted or were complicit in propagating such stereotypes. ↵

- The film De Voortrekkers chronicles the Boers’ migration from Cape Colony during the 1830s to escape British rule. ↵

- The title They Built a Nation is the literal English translation of the film, but it is also common to see the film referred to as Building a Nation. ↵

- Direct quotation from original abstract with essay. ↵

- Direct quotation from original abstract with essay. ↵

- Direct quotation from original abstract with essay. ↵

- Direct quotation from original abstract with essay. ↵

- See Rogin, “The Sword,” for an alternative reading. ↵

- Direct quotation from original abstract with essay. ↵

- Direct quotation from original abstract with essay. ↵