7.3 Benefits and impacts of conventional agriculture

Benefits

Conventional farming developed because it does a good job of producing crops and profits. In the aftermath of World War II, soil processes were poorly understood, the agricultural areas of the world had deep, rich, organic layers, and technology was leading to progress in many areas. Many developments and expansions of that era resulted in unintended environmental consequences due to limited understanding of environmental processes – DDT, acid rain, cheap gasoline, cheap fertilizer … Most started with benefits. The Green Revolution of the latter part of the 20th century dramatically reduced hunger around the world. By increasing yields on productive land, it prevented large areas of less productive land from being put into production to feed the world’s growing population, also staving off related GHG production, biodiversity loss, and other environmental impacts. Fewer farm workers were needed to produce food, allowing more people to seek higher paying jobs.

Tillage

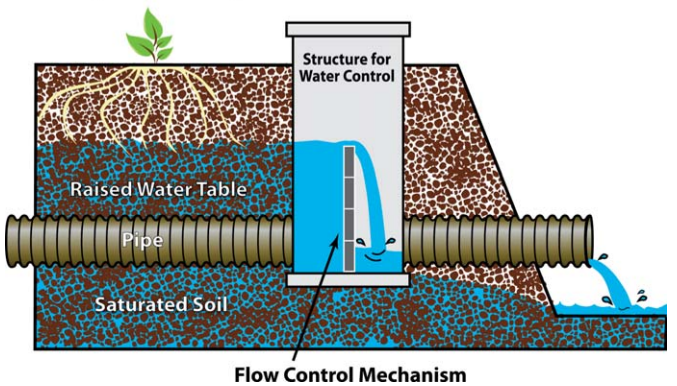

Conventional farming is economically efficient if conservation of the soil resource is not part of the calculation. Tillage, the process of plowing and turning the soil in spring prior to planting seeds, dries and warms the soil, speeding initial crop growth, and killing weeds without the use of herbicides (Fig 1). In colder climates and on compacted soils, tillage is particularly good at improving yields.

Drainage and irrigation

Wetland soils are typically rich in nutrients, and such soils are often drained to allow access for agriculture. Waterlogged soils are only conducive to a few crops (primarily rice), and cannot be worked by usual farm machinery, which requires solid ground.

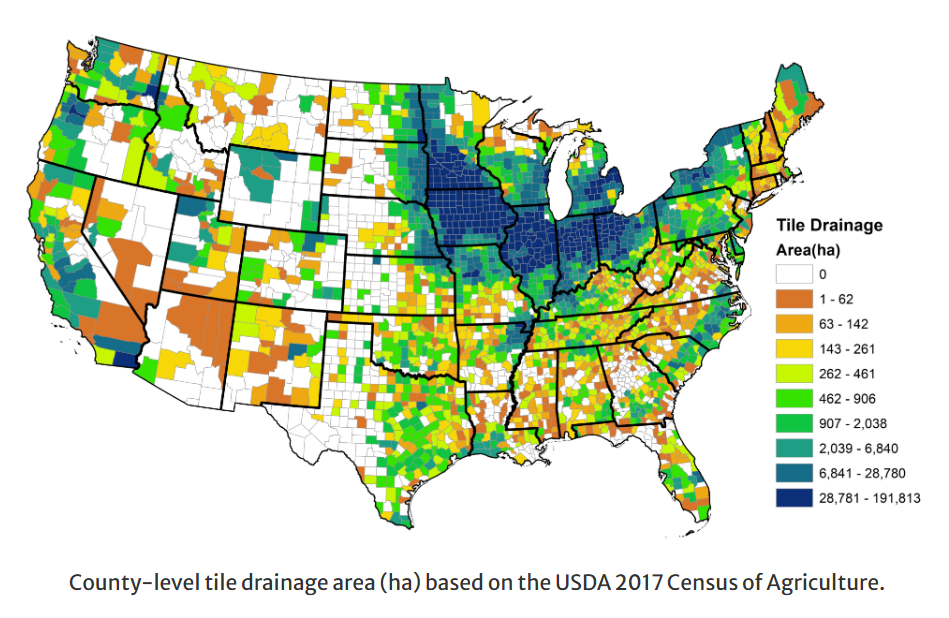

In the US, tile drainage (perforated pipes) is placed underground throughout fields to carry excess water to drainage ditches at the edges of fields (Fig 2). In the state with highest use, Iowa, approximately 53% of cropland is drained in this way.[1] Tile drainage is used extensively in the US, but most intensively in the Midwest (Fig 3). Artificial drainage is used worldwide in areas of intensive agriculture.

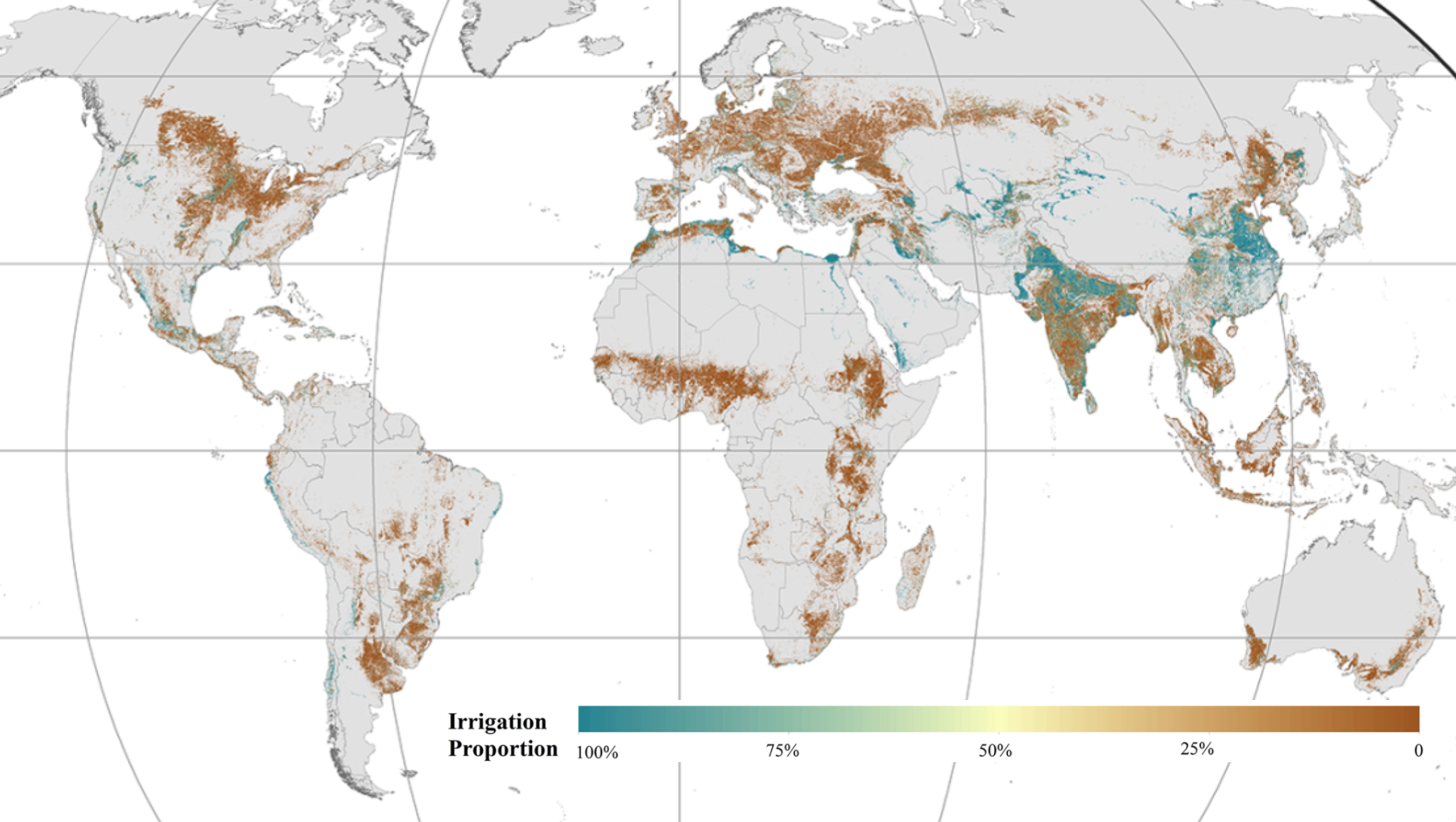

Irrigation is used to supplement water to crops, throughout the world (Fig 4). Gravity-fed methods run water downhill without mechanical assistance and are used to flood entire fields, for example for rice, or to run water into furrows. Mechanization allows sprinklers to be fixed or that can move using electrical power either in a line that “walks” through the field or from a central water supply in central-pivot irrigation (cheaper than linear systems; creates a circle of irrigated area; Fig 5). Drip irrigation is most expensive to employ, but allows precise delivery both in quantity and in location. Irrigation relies on local surface or groundwater. Irrigation increases the total area available for agriculture and also changes the amount of land that is suitable for specific crops.

Drawbacks

Tillage

Among the soil processes unknown as conventional agriculture was taking over industrial food production was the link between mycorrhizal fungi and plants of many kinds, including crops. Section 7.2 introduces the importance of these fungal-plant partnerships.

The form of mycorrhizal fungi in the soil – a dense, fine network or mycelium of threadlike hyphae – as much as 100 m per cubic centimeter of soil (a football field length in a quarter teaspoon)[2] – makes them vulnerable to plowing. Plow blades shred the networks that bring water and nutrients to plants, making fertilizers and irrigation more necessary and reducing resilience.

Tilling also destroys the crumb-like aggregate texture of good agricultural soil that facilitates good root growth, aids water percolation into the soil and allows oxygen to penetrate to deeper roots. It kills beneficial soil organisms such as earthworms (which also contribute bioglues that create good aggregate structure). Although it fluffs up the upper layer of soil, tilling creates a layer of compaction below the plow-blade depth, reducing root penetration and water percolation to greater depths in the soil, where water might remain available during droughts. The drying effect that allows soils to warm earlier in the growing season reduces water percolation and availability, potentially hastening agricultural drought during dry seasons. And by reducing deep infiltration, killing fungi, and reducing the amount of bioglue in the soil, tilling substantially increases erosion, even on comparatively flat ground (Figu 6; note the ditch in the foreground).

Erosion carries soil into nearby receiving waters, but not only soil. Runoff carries dissolved nutrients, contributing to eutrophication and reducing dissolved oxygen. Sediment builds up in streams, burying stream bottoms in muck and destroying spawning habitat for fish and invertebrates. Soil particles and algae reduce water clarity. Runoff also carries herbicides, insecticides and other pesticides in water and adsorbed to soil particles, potentially poisoning aquatic life and humans and wildlife that drink the water.

Finally, tillage exposes deeper soil to oxygen, hastening the decomposition of organic material and decreasing organic material and thus C stored in the soil. Organic material contributes to nutrient- and water-holding capacity of soil, and sequesters carbon, as well as providing nutrients for bacteria and fungi. By reducing C in soil, tillage contributes to climate change.

Drainage and Irrigation

Drainage water coming off of agricultural fields carries with it some of the various substances applied to the fields, as described above. Drainage may help to conserve soil by minimizing runoff from across the top of the soil, but dissolved substances will percolate into the drainage system and contribute to water pollution, including eutrophication. Depending on how well the amount of drainage is controlled, it can also cause fields to become dry sooner than necessary, during a drought.

Irrigation expands the footprint of agriculture, increases yields of high-value crops and confers resilience against drought. But it can only do so as long as water remains available. Because irrigation can increase productivity and value in agriculture, it can also be associated with depleting local water resources, particularly groundwater in confined aquifers that cannot be recharged. Aquifers on every continent that supports agriculture are included in the list of such aquifers, as we saw in section 4.2 of the Water Availability chapter.

Fertilizers

Both natural and synthetics fertilizers are used in conventional agriculture. Manure from livestock is a common natural fertilizer rich in many nutrients, particularly nitrogen and phosphorus. By far the largest amounts of synthetic fertilizers are bioavailable forms of nitrogen – ammonium nitrate, ammonia, and urea – and bioavailable forms of phosphorus – phosphates. Additional nutrients may be added depending on local soil makeup and crop needs.

Fertilizers support early and rapid growth of crops; some commercial crops are bred or engineered to use nutrients rapidly. In the midwestern US, fall application of fertilizers, months ahead of crop emergence, is common. Drier fields in fall are easier and safer to access, and moving fertilizing to fall reduces the number of field entries in spring. However, leaving fertilizers in the field over winter increases the opportunity for nutrients to leach from soils into local waterways. Because fertilizers are relatively inexpensive in the US, the loss is economically supportable, but environmentally harmful. For the same reason, farmers often overapply fertilizers, increasing leaching.

Fertilizer run-off is a major source of nutrient pollution (see Chapter 3). Nitrates, in particular, are highly soluble. Some common nitrogen fertilizers acidify soils, and acidification reduces soil ability to bind nutrients, increasing the tendency for nitrates to be washed from fields and into rivers and lakes. Nutrient pollution leads to “dead zones” in estuaries that drain agricultural land. In these areas, both commercial and recreational fisheries suffer economic losses as marine organisms leave the area or die from lack of oxygen. In severe cases of freshwater pollution by nitrates, infants may suffer from blue-baby syndrome, which can be lethal.

Limits on nutrients in farm runoff are managed by states in the US, because runoff is a nonpoint process – not all state impose specific limits. Where they exist, nutrient limits can be difficult to enforce because nutrients are everywhere and all farmers apply them. Nutrient pollution is widespread, as a result.

Fertilizer use is not high everywhere. Africa, particularly sub-Saharan Africa, uses approximately 20 kg/ha of fertilizer (17.8 lbs/acre), whereas the global average is approximately 135 kg/ha (120 lbs/acre). [3]Fertilizer is largely imported, much of it, previously, from Ukraine and Russia, so that supply chains have been disrupted and prices have increased since Russia invaded Ukraine. In addition, distribution and delivery are hampered by infrastructural problems. Reduced availability of fertilizer is one of the reasons for high food insecurity in Africa.

Knowledge Check

Take a moment to complete the short quiz below to assess your understanding of this section. Read each question carefully and refer back to the content as needed. This quiz is not graded – it’s simply an opportunity for you to reflect on what you’ve learned and reinforce key concepts.

Media Attributions

- Tillage after corn harvest.CC0 © Wikideas1 is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- pipe drainage diagram.NRCS © US National Resource Conservation Service is licensed under a Public Domain license

- US tile drainage.CC BY © Prasanth Valayamkunnath is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Satellite image of part of Kansas in the US, showing high-density use of center-pivot irrigation.NASA.Public domain © US National Aeronautics and Space Administration is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Global irrigated area © Fuyou Tian et al. is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- corn plants on a field flooded damage after heavy rain © NokHoOkNoi

- Zulauf C & Brown B. 2019. Use of tile, 2017 US Census of Agriculture. Farmdoc Daily 9:141. https://farmdocdaily.illinois.edu/2019/08/use-of-tile-2017-us-census-of-agriculture.html ↵

- Hawkins H-J et al. 2023. Mycorrhizal mycelium as a global carbon pool. Current Biology 33:R560-R573. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2023.02.027 ↵

- Njoroge S et al. 2023. The impact of the global fertilizer crisis in Africa. African Plant Nutrition Institute. https://growingafrica.pub/the-impact-of-the-global-fertilizer-crisis-in-africa/ ↵