16 Hearing words or word boundaries in spoken Spanish

Bottleneck: perceiving spoken word boundaries

As I reflected on the things I do automatically compared to what a new learner experiences, like my own kids, I realized after repeatedly repeating, “You know this word.” While my kids knew individual words and could usually recognize them when spoken in isolation, they stopped being recognizable once those words appeared in a sentence. Instead, they became a stream of unintelligible sounds. This same type of scenario has repeated with my undergraduate students, often without the bare honesty of one’s children. The bottleneck, in simple terms, is the inability to recognize words in spoken utterances. This challenge is partly due to differences in marking word boundaries in Spanish, typically overlapping compared to English, which often has very explicit word boundary markers.

In a recent research project, we explored in a snapshot format how advanced undergraduate learners, advanced graduate students, and native speakers produced words in context across boundaries that end and begin with vowels.

- Willis, Erik W., D. Eric Holt, and Carly Carver. 2025. Resolving contiguous vowels across word boundaries in Spanish: L2 learners, levels, and tasks, Linguistik online, 134: 27-50. https://doi.org/10.13092/lo.134.12177

In other work, we explored the resyllabification of word-final /s/ across word boundaries.

- Willis, Erik W. and Magaly Gastelum. 2024. “Learners with attachment issues: The challenges of L2 consonantal resyllabification.” In Current Approaches to Spanish and Portuguese Second Language Phonology. NC State University.

The next steps are to explore and document the perceptual challenges described below in the bottleneck and then create materials to teach and practice the ability to parse words across word boundaries.

Combining sounds across words

“They are speaking so fast” is a common complaint by language learners. While there may indeed be variations in native speaker speech rate, the primary difficulty our learners face is due to how the words blend together in Spanish in ways that are different from the first language, not the speed per se. The learners often are unable to process the flow of sound into meaningful words due to the unique overlapping in Spanish. This chapter will review two contexts of unique merging that may cause learners to feel confused. The contexts occur at word boundaries and include the blending of contiguous vowels called linking or synalepha, the reassociation of a word-final consonant with a vowel in the next syllable called resyllabification.

1. Blends: contiguous vowels across word boundaries

English will often separate words with a glottal stop to ensure that the listener is able to identify or parse the individual words. The definite article a before a word beginning with a vowel such as apple will typically be produced with an extra “n” to identify them as separate words, “an apple”.

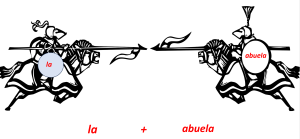

In contrast, Spanish will blend or merge two words that end and begin with vowels. This blending at the word level humorisitically demonstrated at the single word level in the PBS program, Reading between the Lións in the segment titled, Gwains’ Word. In this segment, two knights, each that represent part of a word, begin a joust. The two sets of letters come together or blend at the moment of impact between the knights.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JmQim8JjE0Y

In Spanish, each knight would represent the two distinct words that blend into a single run-together sound or chunk of multiple words. For example, in Spanish, the sound a in the word la ‘the’ combines with sound a in the word abuela ‘grandma’ to create a single chunk of sound with three syllables. This is not a common practice in native English.

In this case, the word pair < la abuela > will be pronounced as a single merged chunk of sound [la-β̞u̯e-la].

The challenge for native speakers of English, as they learn Spanish, is that they are unaccustomed to the merging of vowels between two words and then have trouble hearing the chunk as two words.

Practice

2. Resyllabification (my bumper is on your hitch)

Certain sounds tend to clump together when there are consonants and vowels. In English, consonants regularly occur at the end of a word and serve to mark the word boundary. In Spanish, there are very few consonants that occur at the word at the end of a word. If there is a vowel at the beginning of the next word, the previous consonant will “jump” to the next vowel and form part of its syllable, las amigas -> [la-sa-mi-gas].

Supose there are two cars and the rear car crashes into the front car. The bumper of the following car could stay on its original car (English), or become attached to the car that was struck (Spanish) as in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Reattached bumper to truck tailgate (Photo credit: https://www.ford-trucks.com/articles/undamaged-ford-super-duty-keeps-souvenir-hit-run/)

Similar to the bumper, the last consonant of a word will typically become associated with the vowel of the next word in the pronunciation of syllables in Spanish.

Los otros is chunked or resyllabified as [lo-so-tros]. The <s> of los joins the <o>vowel of the next word.

In English, the prefix sub ‘under’ is pronounced as a single unit when compounded with another word like atomic. The pronunciation would be divided into syllables “sub-a-tom-ic”. Spanish on the other hand prefers to connect final consonants with following vowels instead of ending a syllable with a consonant. This difference is illustrated in the location of the <b> shown in (1).

- English sub-a-tom-ic

Spanish su-ba-to-mi-co

This reassociation/resyllabification or linking of a word-final consonant is characteristic of native Spanish and is a feature of fluid Spanish because the sounds literally flow together. This process of resyllabication is common with the consonants that can occur at the end of a word in Spanish and includes the letters <s>, <n>, <l>, <d>, <z>.

‘The friends’ Los amigos -> lo-sa-mi-gos

‘A friend’ Un amigo -> u-na-mi-go

‘The friend’ El amigo -> e-la-mi-go

“Half friend” Mitad amigo -> mi-ta-da-mi-go

‘Happy friend’ Feliz amigo -> fe-li-za-mi-go

We can extend this pattern into complete utterances. * Letters in red indicate word-final consonants that resyllabify with the following word.

Spelling with word boundary spaces <Las abejas han entrado en un edificio.>

Spelling without spaces <Lasabejashanentradoenunedificio>

Spelling with syllabification <La-sa-be-ja-sha-nen-tra-doe-nu-ne-di-fi-cio>

Spelling with word boundary spaces <Mis hermanas tienen unos libros antiguos.>

<Mi-sher-ma-nas-tie-ne-nu-nos-li-bro-san-ti-guos.>

Read and record the sentences above and practice the resyllabification patterns explained.