Part One: Fundamentals of Environmental Geology

Lab 5 Reading: Igneous Rocks

Igneous Rocks

Karen Tefend

INTRODUCTION

All rocks found on the Earth are classified into one of three groups: igneous, sed- imentary, or metamorphic. This rock classification is based on the origin of each of these rock types, or if you prefer, based on the rock-forming process that formed the rock. The focus of this chapter will be on igneous rocks, which are the only rocks that form from what was once a molten or liquid state. Therefore, based on their mode of origin, igneous rocks are defined as those rock types that form by the cooling of magma or lava. You would be right in thinking that there is more to the classification of igneous rocks than stated in the previous sentence, as there are dozens of different igneous rocks that are considered commonplace, and dozens of more types that are less common, and also quite a few igneous rock types that are quite scarce, yet each igneous rock has a name that distinguishes it from all the rest of the igneous group of rocks. So, if they all start out as molten material (magma or lava), which must harden to form a rock, then it is logical to assume that these igneous rocks differ from one an- other primarily due to: 1) the original composition of the molten material from which the rock is derived, and 2) the cooling process of the molten material that ended up forming the rock. These two parameters define the classification of igneous rocks, which are simplified into the two terms: composition and texture. Igneous rock composition refers to what is in the rock (the chemical composition or the minerals that are present), and the word texture refers to the features that we see in the rock such as the mineral sizes or the presence of glass, fragmented material, or vesicles (holes) in the igneous rock.

Learning Outcomes

After completing this chapter, you should be able to:

- Classify igneous rock types based on color, texture, and mafic color index

- Identify, when possible, the minerals present in an igneous rock

- Determine the cooling history of the igneous rock

Key Terms

- Aphanitic

- Extrusive

- Felsic (Silicic)

- Ferromagnesian

- Glassy

- Intermediate

- Intrusive

- Mafic

- Nonferromagnesian

- Phaneritic

- Phenocryst

- Plutonic

- Porphyritic

- Ultramafic

- Vesicular

- Volcanic

IGNEOUS ROCK ORIGIN

Magma Composition

It seems like a bad joke, but before any igneous rock can form, there must be molten material known as magma produced, which means that you must first have a rock to melt to make magma in order for it to cool and become an igneous rock. Which brings more questions: what rock melted to form the magma? Was there more than one rock type that melted to form that magma? Did the rocks completely melt, or did only certain minerals inside of those rocks melt (a process known as partial melting)? Once that melted material formed, what happened to it next? Did some other process occur to change the composition of that magma, before ending up as the igneous rock that we are studying? These are just a few of the questions that a person should consider when studying the origin of igneous rocks.

Most rocks (there are very few exceptions!) contain minerals that are crystal- line solids composed of the chemical elements. In your chapter on minerals you learned that the most common minerals belong to a group known as the silicate minerals, so it makes sense that magmas form from the melting of rocks that most likely contain abundant silicate minerals. However all minerals (not just the silicates) have a certain set of conditions, such as temperature, at which they can melt. Since rocks contain a mixture of minerals it is easy to see how only some of the minerals in a rock may melt, and why others stay as a solid. Furthermore, the temperature conditions are important, as only minerals that can melt at “lower” temperatures (such as 600C) may experience melting, whereas the temperature would have to increase (for example, to 1200C) in order for other minerals to also melt (remember the lower temperature minerals are still melting) and thus add their chemical components to the magma that is being generated. This brings up an important point: even if the same types of rocks are melting, we can generate different magma compositions purely by melting at different temperatures!

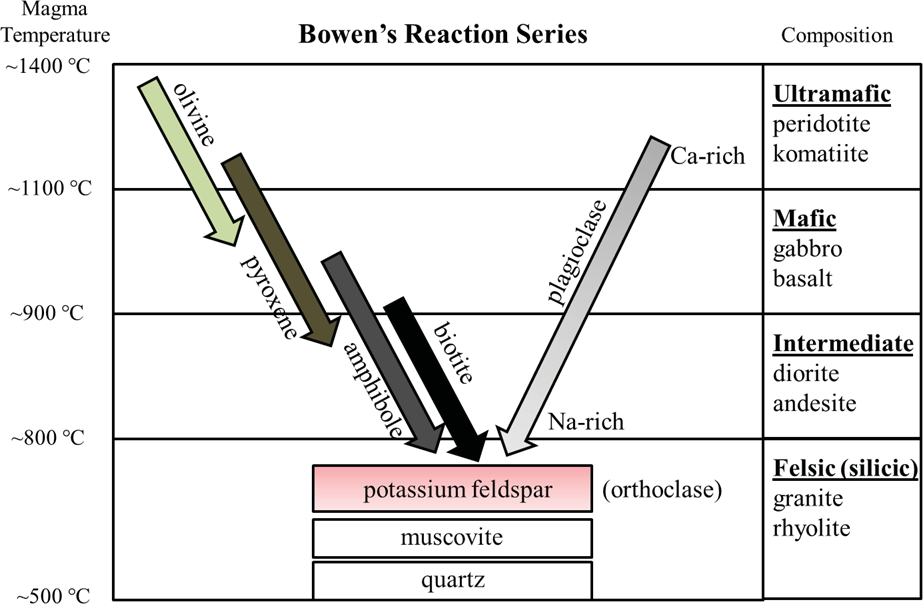

Once magma is generated, it will eventually start to rise upward through the Earth’s lithosphere, as magma is more buoyant than the source rock that generated it. This separation of the magma from the source region will result in new thermal conditions as the magma moves away from the heated portion of the litho- sphere and encounters cooler rocks, which results in the magma also cooling. As with melting, minerals also have a certain set of conditions at which they form, or crystallize, from within a cooling magma body. You would be right in thinking that the sequence of mineral crystallization is the opposite sequence of crystal melting. The sequence of mineral formation from magma has been experimentally determined by Norman L. Bowen in the early 1900’s, and the now famous Bowen’s reaction series appears in countless textbooks and lab manuals (Figure 8.1).

Figure 8.1 | Bowen’s Reaction Series, showing the progression of mineral crystallization as magma temperatures drop from ~1400 °C to ~500 °C. Note the corresponding names for igneous rock composition (underlined and bolded) and some example rock types within each compositional group.

Author: Karen Tefend Source: Original Work License: CC BY-SA 3.0

There can be more than one mineral type crystallizing within the cooling mag- ma, as the arrows in Figure 8.1 demonstrate. The minerals on the left side of Bowen’s reaction series are referred to as a discontinuous series, as these minerals (olivine, pyroxene, amphibole, and biotite) all remove the iron (Fe), magnesium (Mg), and manganese (Mn) from the magma during crystallization, but do so at certain temperature ranges. These iron- and magnesium-rich minerals are referred to as ferromagnesian minerals (ferro = iron) and are usually green, dark gray, or black in color due to the absorption of visible light by iron and magnesium atoms. On the right side of Bowen’s reaction series is a long arrow labelled plagioclase feldspar. Plagioclase crystallizes over a large temperature interval and represents a continuous series of crystallization even though its composition changes from calcium (Ca) rich to sodium (Na) rich. As the magma temperature drops and plagioclase first starts to crystallize (form), it will take in the calcium atoms into the crystal structure, but as magma temperatures continue to drop, plagioclase takes in sodium atoms preferentially. As a result, the higher temperature calcium-rich plagioclase is dark gray in color due to the high calcium content, but the lower temperature sodium-rich plagioclase is white due to the high sodium content. Finally, at the bottom of the graph in Figure 8.1, we see that three more minerals can form as temperatures continue to drop. These minerals (potassium feldspar, muscovite, and quartz) are considered to be the “low temperature minerals”, as they are the last to form during cooling, and therefore first to melt as a rock is heated. The previous removal of iron and magnesium from the magma results in the formation of the lat- est forming minerals that are deficient in these chemical elements; these minerals are referred to as nonferromagnesian minerals, which are much lighter in color. For example, the potassium-rich feldspar (also known as orthoclase) can be a pale pink or white in color. The references to mineral color are necessary, as the color of any mineral is primarily due to the chemical elements that are in the minerals, and therefore the color of an igneous rock will be dependent on the mineral content (or chemical composition) of the rock.

IGNEOUS ROCK COMPOSITION

Often added to the Bowen’s reaction series diagram are the igneous rock classifications as well as example igneous rock names that are entirely dependent on the minerals that are found in them. For example, you can expect to find abundant olivine, and maybe a little pyroxene and a little Ca-rich plagioclase, in an ultra-mafic rock called peridotite or komatiite, or that pyroxene, plagioclase, and possibly some olivine or amphibole may be present in a mafic rock such as gabbro or basalt. You can also expect to see quartz, muscovite, potassium feldspar, and maybe a little biotite and Na-rich plagioclase in a felsic (or silicic) rock such as granite or rhyolite. Figure 8.1 demonstrates nicely that the classification of an igneous rock depends partly on the minerals that may be present in the rock, and since the minerals have certain colors due to their chemical makeup, then the rocks must have certain colors. For example, a rock composed of mostly olivine will be green in color due to olivine’s green color; such a rock would be called ultramafic. A rock that has a large amount of ferromagnesian minerals in it will be a dark-colored rock because the ferromagnesian minerals (other than olivine) tend to be dark colored; an igneous rock that is dark in color is called a mafic rock (“ma-” comes from magnesium, and “fic” from ferric iron). An igneous rock with a large amount of nonferromagnesian minerals will be light in color, such as the silicic or felsic rocks (“fel” from feldspar, and “sic” from silica-rich quartz). So, based on color alone, we’ve been able to start classifying the igneous rocks.

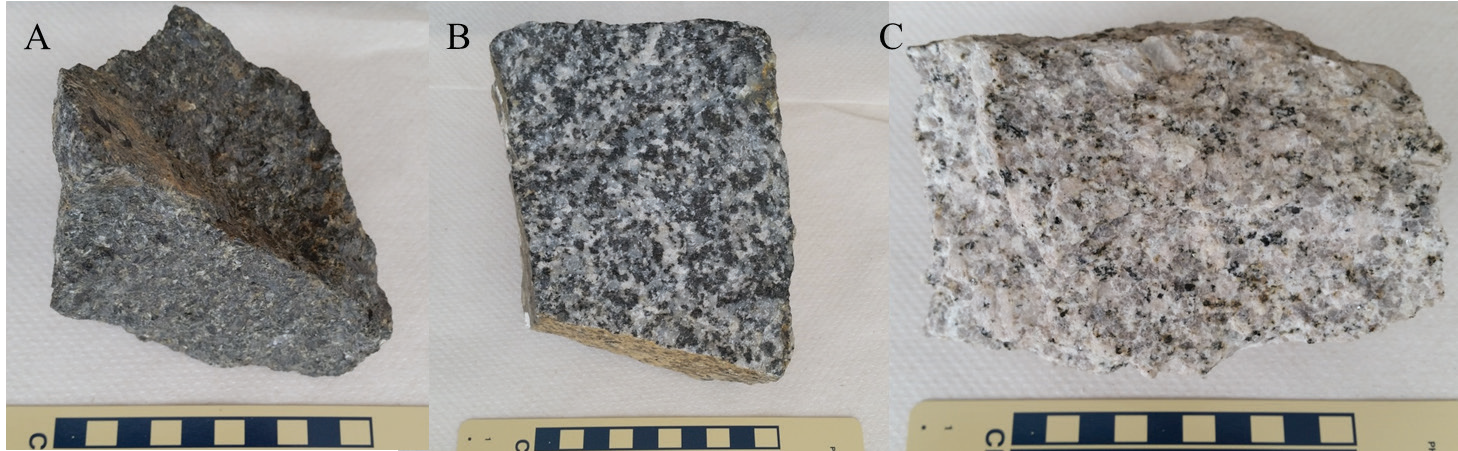

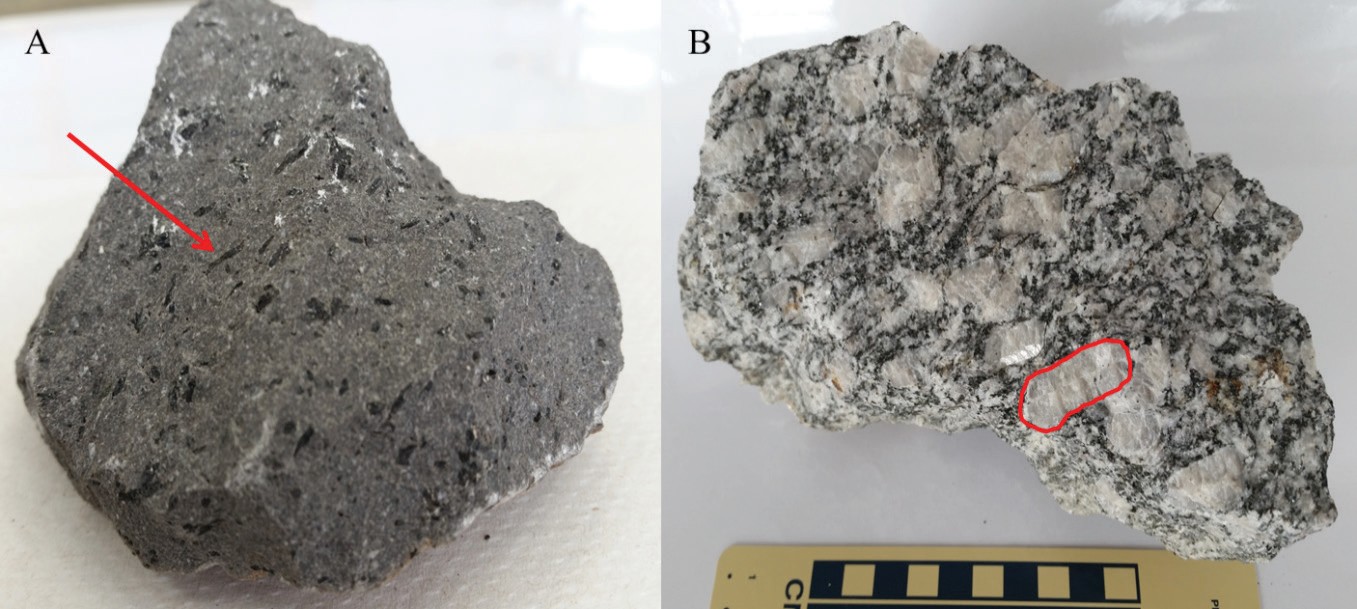

In Figure 8.2 are examples of igneous rocks that represent the mafic and felsic rock compositions (Figures 8.2A and 8.2C, respectively), as well as an intermediate rock type (Figure 8.2B). Notice that the felsic rocks can have a small amount of dark-colored ferromagnesian minerals, but is predominately composed of light-colored minerals, whereas the mafic rock has a higher percentage of dark-colored ferromagnesian minerals, which results in a darker-colored rock. A rock that is considered intermediate between the mafic and felsic rocks is truly an intermediate in terms of the color and mineral composition; such a rock would have less ferromagnesian minerals than the mafic rocks, yet more ferromagnesian minerals than the felsic rocks.

Figure 8.2 | Examples of igneous rocks from the mafic (A), intermediate (B), and felsic (C) rock compositions. Photo

scale on bottom is in centimeters.

Author: Karen Tefend Source: Original Work License: CC BY-SA 3.0

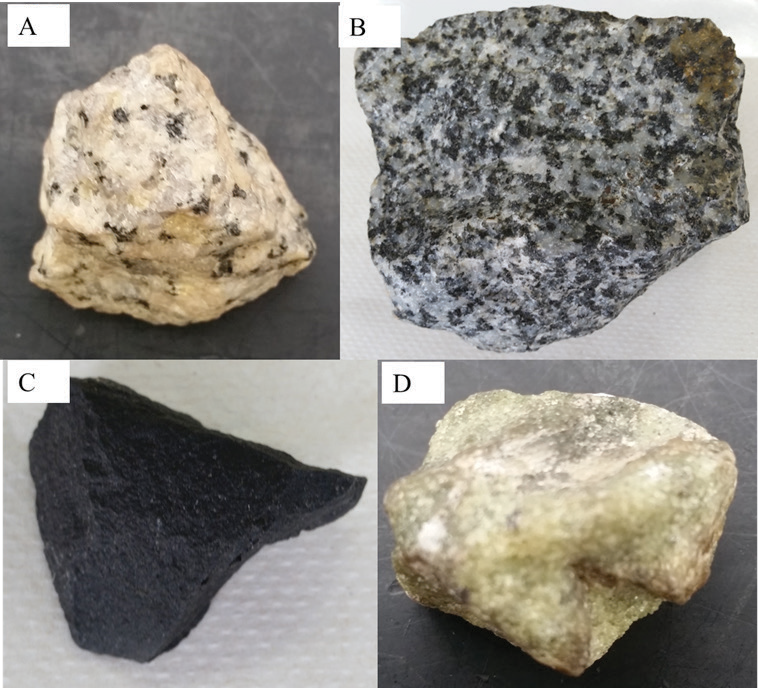

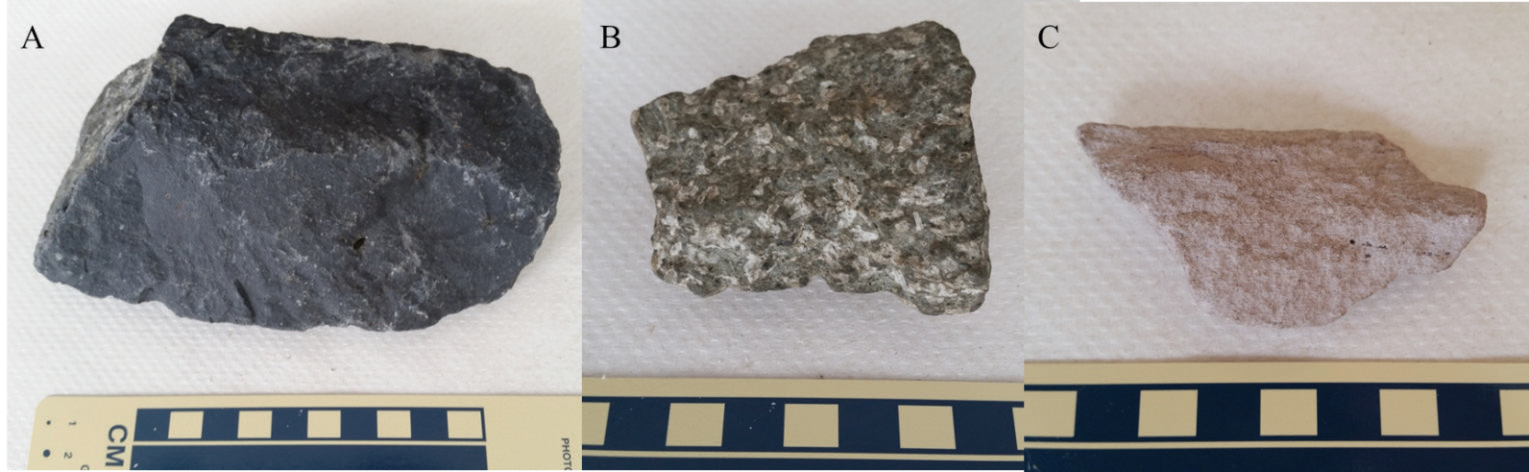

As previously mentioned, classifying rocks into one of the igneous rock compositions (ultramafic, mafic, intermediate, and felsic) depends on the minerals that each rock contains. Identification of the minerals can be difficult in rocks such as in Figure 8.2A, as the majority of minerals are dark in color and it can be difficult to distinguish each mineral. An easy method of determining the igneous rock com- position is by determining the percentage of dark-colored minerals in the rock, without trying to identify the actual minerals present; this method of classification relies on a mafic color index (MCI), where the term mafic refers to any dark gray, black or green colored mineral (Figure 8.3). Igneous rocks with 0-15% dark colored minerals (or 0-15% MCI) are the felsic rocks (Figure 8.3A), igneous rocks with 46-85% MCI are the mafic rocks (Figure 8.3C), and igneous rocks with over 85% MCI are considered ultramafic (Figure 8.3D). This means that any rock with an intermediate composition or with a 16-45% MCI is an intermediate igneous rock (Figure 8.3B). Estimating the percentage of dark-colored minerals is only possible if the minerals are large enough to see; in that case a person can still recognize a mafic rock by its dark-colored appearance, and a felsic rock by its light-colored appearance. An intermediate rock will be somewhat lighter than a mafic rock, yet darker than a felsic rock. Finally, an ultramafic rock is typically green in color, due to the large amount of green-colored olivine in the rock. Such rocks that contain minerals that are too small to see are shown in Figure 8.4; note that you can still distinguish between mafic (Figure 8.4A), intermediate (Figure 8.4B) and felsic (Figure 8.4C) by the overall color of the rock. The intermediate igneous rock in Figure 8.4B does have a few visible phenocrysts; this odd texture will be covered later in this chapter.

Figure 8.3 | Examples of how igneous rocks can be classified using the Mafic Color Index (MCI), which is a visual classification based on the amount of ferromagnesian minerals in the rock: (A) The small amount of tiny black phenocrysts (biotite) gives this rock a 0-15% MCI value; (B) numerous dark phenocrysts (amphibole) gives this rock a 16-45% MCI value; (C) this rock lacks visible phenocrysts, but the black color in this rock results in a 46-85% MCI value; (D) this rock is entirely green in color due to the overwhelming amount of olivine. Any rock with this much olivine is always classified as having over 85% MCI values.

Author: Karen Tefend Source: Original Work License: CC BY-SA 3.0

Figure 8.4 | Examples of igneous rocks from the mafic (A), intermediate (B), and felsic (C) rock compositions. Notice the difference in appearance between these rocks and those in Figure 8.2

Author: Karen Tefend Source: Original Work License: CC BY-SA 3.0

IGNEOUS ROCK TEXTURE

The classification of igneous rocks is based not just on composition, but also on texture. As mentioned earlier, texture refers to the features that we see in the rock such as the mineral sizes or the presence of glass, fragmented material, or vesicles (holes) in the igneous rock. We will cover mineral crystal sizes and vesi- cles in this section.

Since the crystals or phenocrysts form while the magma is cooling, then the size of the crystals must have something to do with the cooling process. Recall that each mineral derives its chemical composition directly from the magma, and that each mineral has a certain temperature interval during which that particular mineral can form. The chemical elements that become part of the mineral must migrate from the liquid magma to link or bond with other elements in a certain way to form the crystal structure that is unique for that mineral. What do you think will happen if the magma’s temperature drops quickly, or if the magma’s tempera- ture drops slowly? Either way, the time allowed for the migration of the chemical elements to form a crystal is affected. When magma cools slowly, there is plenty of time for the migration of the needed chemical elements to form a certain mineral; that particular mineral can become quite large in size, large enough for a person to see without the aid of a microscope. As a result, this igneous rock with its visible minerals is said to have a phaneritic texture (phan = large). The rock samples shown in Figure 8.2 are all phaneritic rocks. Figure 8.2A is a phaneritic mafic rock called gabbro, Figures 8.2B and 8.3B are a phaneritic intermediate rock called diorite, and the rock in Figure 8.2C is a phaneritic felsic rock known as granite. If you refer back to Figure 8.1 (Bowen’s reaction series) you will see that these rock names are listed on the right side of the diagram.

Magma that cools relatively quickly will have the opposite result as described above; there is less time for the migration of the chemical elements to form a mineral, and as a result the minerals will not have time to form large crystals. Therefore, many small crystals of a particular mineral will form in the magma. Igneous rocks that are composed of crystals too small to see (unless you have a microscope) are called aphanitic igneous rocks. Figure 8.3C, 8.4A and 8.4C are aphanitic rocks; because Figure 8.3C (and 8.4A) is dark in color, it is a mafic aphanitic rock called basalt. The felsic rock in Figure 8.4C is called rhyolite. It is important to note that basalt and gabbro are both mafic rocks and have the same composition, but one rock represents a magma that cooled fast (basalt), and the other represents a mafic magma that cooled slowly (gabbro). The same can be said for the other rock compositions: the felsic rocks rhyolite and granite have identical compositions but one cooled fast (rhyolite) and the other cooled slower (granite). The intermediate rocks diorite (Figure 8.2B) and andesite (Figure 8.4B) also represent magmas that cooled slow or a bit faster, respectively. Sometimes there are some visible crystals in an otherwise aphanitic rock, such as the andesite in Figure 8.4B. The texture of such a rock is referred to as porphyritic, or more accurately porphyritic-aphanitic since it is a porphyritic andesite, and all andesites are aphanitic. Two different crystal sizes within an igneous rock indicates that the cooling rate of the magma increased; while the magma was cooling slowly, larger crystals can form, but if the magma starts to cool faster, then only small crystals can form. A phaneritic rock can also be referred to as a porphyritic-phaneritic rock if the phaneritic rock con- tains some very large crystals (ie. the size of your thumb!) in addition to the other visible crystals. In Figure 8.6 are two porphyritic rocks: a porphyritic-aphanitic basalt, and a porphyritic-phaneritic granite.

Figure 8.6 | (A) An example of a porphyritic-aphanitic mafic rock with needle-shaped amphibole phenocrysts (arrow points to one phenocryst that is 1cm in length); No other minerals in (A) are large enough to see. (B) An example of a porphyritic-phaneritic felsic rock with large feldspars (outlined phenocryst is 3 cm length). Surrounding these large feldspars are smaller (yet still visible) dark and light colored minerals.

Author: Karen Tefend Source: Original Work License: CC BY-SA 3.0

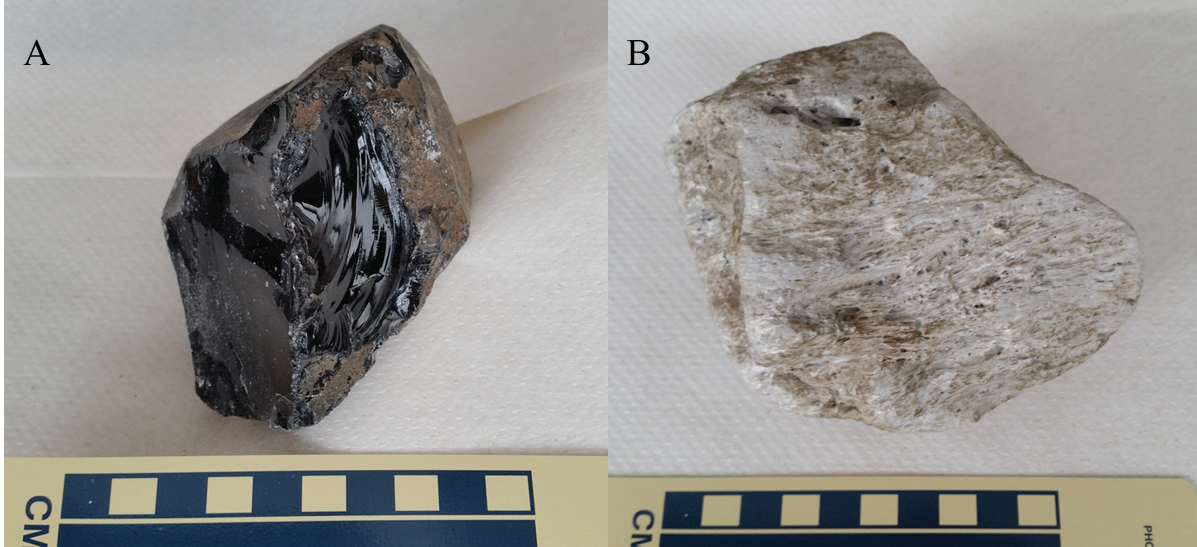

Sometimes the magma cools so quickly that there isn’t time to form any miner- als as the chemical elements in the magma do not have time to migrate into any crystal structure. When this happens, the magma becomes a dense glass called ob- sidian (Figure 8.7A). By definition, glass is a chaotic arrangement of the chemical elements, and therefore not considered to be a mineral; igneous rocks composed primarily of glass are said to have a glassy texture. The identification of a glassy rock such as obsidian is easy once you recall the properties of glass; any thick glass pane or a glass bottle that is broken will have this smooth, curve shaped pattern on the broken edge called conchoidal fracture (this was covered in your mineral chapter). Even though obsidian is naturally occurring, and not man made, it still breaks in this conchoidal pattern. If you look closely at the obsidian in Figure 8.7A, you will see the curved (conchoidal) surfaces by noticing the shiny pattern on the rock. Ob- sidian appears quite dark in color regardless of its composition because it is a dense glass, and light cannot pass through this thick glass; however, if the edges of the obsidian sample are thin enough, you may be able to see through the glass.

Figure 8.7 | Igneous rocks with glassy texture: obsidian (A) and pumice (B).

Author: Karen Tefend Source: Original Work License: CC BY-SA 3.0

In Figure 8.7B there is another igneous rock that is also composed primarily of glass due to a very fast rate of magma cooling. This rock is called pumice, and is commonly referred to as the rock that floats on water due to its low density. The glass in this rock is stretched out into very fine fibers of glass which formed during the erup- tive phase of a volcano. Because these fibers are so thin, they are easy to break (unlike the dense obsidian) and any conchoidal fractures on these fibers are too small to see without the aid of a microscope. Pumice can have any composition (felsic to mafic), but unlike obsidian the color of the pumice can be used to determine the magma composition, as felsic pumice is always light in color and mafic pumice will be dark in color. Mafic pumice with a dark grey, red or black color is also known as scoria.

IGNEOUS ROCK FORMATION—PLUTONIC VS. VOLCANIC

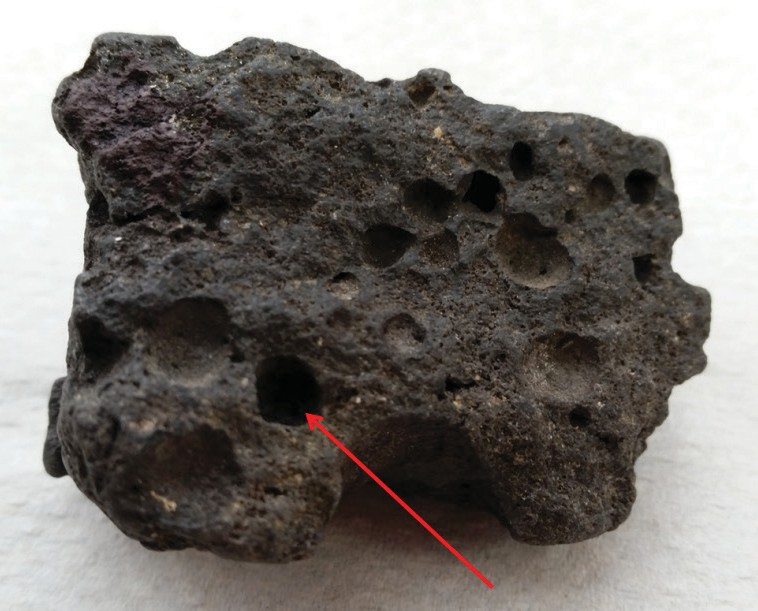

The different crystal sizes and presence or absence of glass in an igneous rock is primarily controlled by the rate of magma cooling. Magmas that cool below the surface of the earth tend to cool slowly, as the surrounding rock acts as an insulator, not unlike a coffee thermos. Most of us are aware that even the most expensive coffee thermos does not prevent your coffee from cooling; it just slows the rate of cooling. Magma that stays below the surface of the earth can take tens of thousands of years to completely crystallize depending on the size of the magma body. Once the magma has completely crystallized, the entire igneous body is called a pluton. Sometimes portions of these plutons are exposed at the earth’s surface where di- rect observation of the rock is possible, and upon inspection of this “plutonic” rock, you would see that it is composed of minerals that are large enough to see without the aid of a microscope. Therefore, any igneous rock sample that is considered to have a phaneritic texture (or porphyritic-phaneritic), is also referred to as a plu- tonic rock. A plutonic rock is also called an intrusive rock as it is derived from magma that intruded the rock layers but never reached the earth’s surface.

Figure 8.8 | An aphanitic mafic rock (basalt), with gas escape structures called vesicles. Arrow points to one vesicle that is ~1cm in diameter. This is an example of another texture type, called vesicular texture, and the name of this rock is a vesicular basalt.

Author: Karen Tefend Source: Original Work License: CC BY-SA 3.0

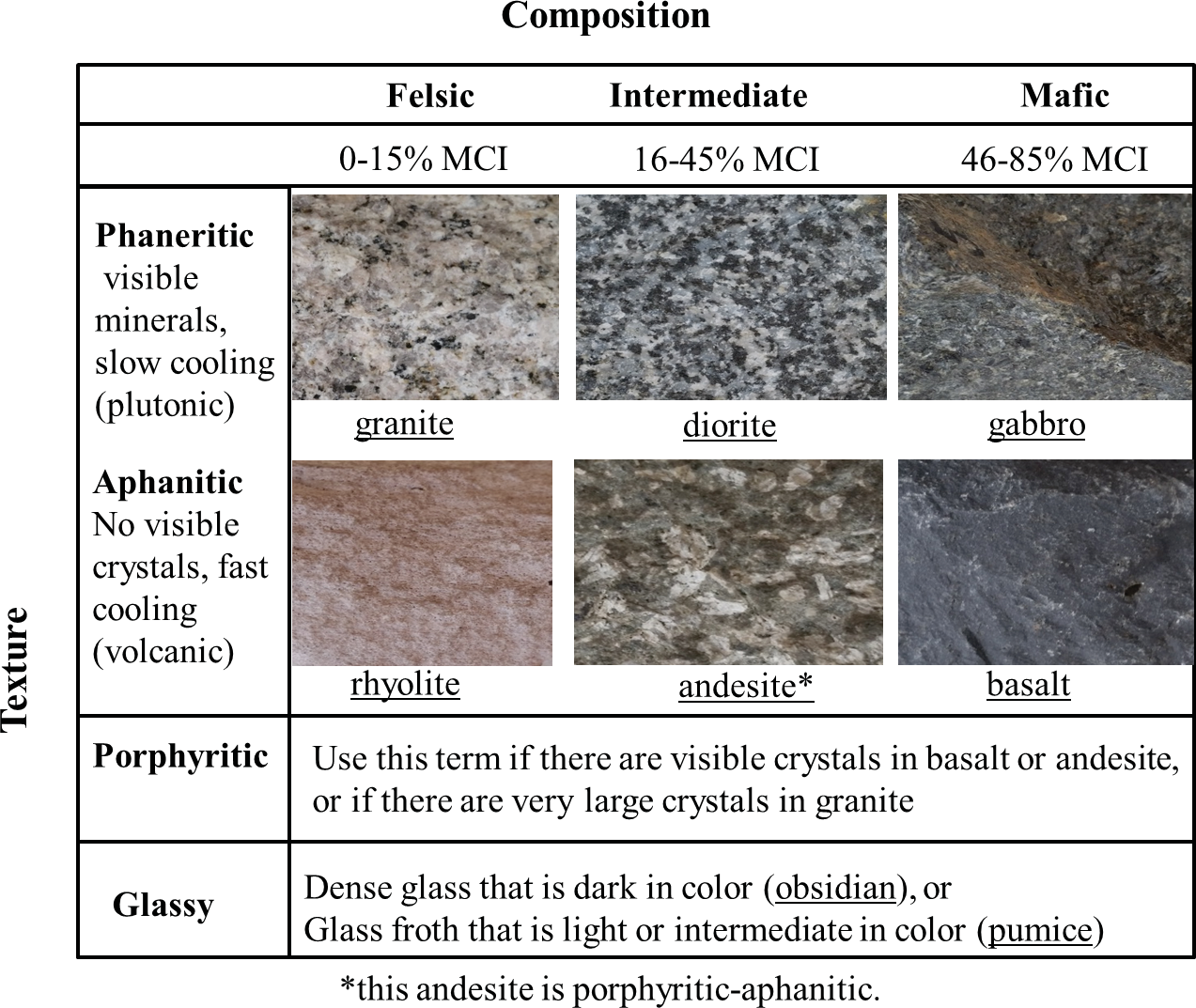

A summary of the terms used to classify the igneous rocks are provided in Figure 8.9 in order to help with the identification of the igneous rock samples provided in your rock kit. Refer to the preceding figures for further help.

Figure 8.9 | Chart showing some common igneous rock textures and compositions. MCI = mafic color index, or the percentage of dark colored ferromagnesian minerals present. Recall that any composition can be phaneritic, aphanitic, porphyritic or glassy. Vesicular texture is not as common and is only seen in some aphanitic rocks.

Author: Karen Tefend Source: Original Work License: CC BY-SA 3.0

Feedback/Errata