Part 4: Learning Activities and Engagement

Effective Asynchronous Discussions

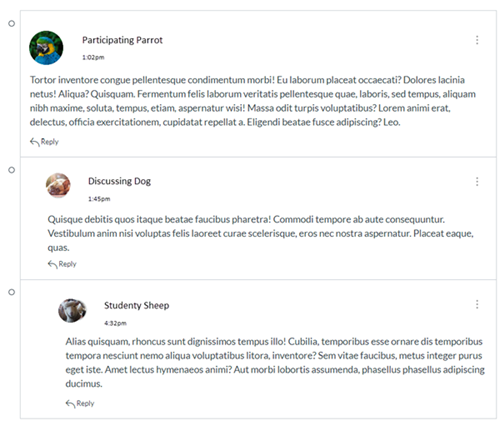

One common type of participation in asynchronous online courses is discussion. Using the Canvas Discussion tool, students can interact with each other in a threaded chat like you see in many forms of social media. While it is lacking social media elements like emoji, it provides features that can be used for a variety of types of online interaction.

One common type of participation in asynchronous online courses is discussion. Using the Canvas Discussion tool, students can interact with each other in a threaded chat like you see in many forms of social media. While it is lacking social media elements like emoji, it provides features that can be used for a variety of types of online interaction.

This section focuses on best practices for discussions, especially those that count toward final grades. You may also find it helpful to have one or two non-graded discussions where students can ask general questions about the class or discuss current events through the lens of the class content.

Use discussions only where there will be actual discussion

The first thing to consider is whether or not your activity is a good fit for a discussion. If you want students to answer questions where the goal is for everyone to have the same answers, don’t use a discussion. If each student is posting the same thing, there is no opportunity for meaningful interaction. Given the question, “What color is the sky?” students know the answer you are looking for is “blue.” Everyone says “blue,” so there is nothing to discuss. These sorts of questions are a much better fit for a quiz or a worksheet-style assignment turned in directly to you.

If you have an idea that involves multiple perspectives or applications of concepts, then a discussion may be what you want.

Make sure the discussion has a clear educational purpose

When thinking about using online discussion forums, the most important thing to think about is your learning objective for the discussion. What is your goal? What are your students supposed to learn and practice in the process of discussing this particular thing? How are they to integrate the course readings, resources, and other reliable sources? While there can be benefits from any sort of interpersonal interaction, graded class interactions should be focused on learning. As the instructor, you are the one to provide that focus and structure.

It is important not only that you know what the purpose of the discussion is, but also that the students know as well. The Transparency in Teaching and Learning (TILT) format for assignment instructions from Section 1 is one way to easily provide students with the purpose, structure, and criteria for the discussion. Being explicit about the purpose of the discussion and how it can help students learn can help gain student buy-in to the activity.

Help students want to participate in discussions

Ideally, the purpose of the discussion should explain why the student should care about this assignment beyond a single grade in a single course. How will they benefit from participating? Discussions where the purpose is to simply show the instructor that you read the book are much less likely to be inherently interesting to students, and appear to be another type of “busywork.”

A common problem in discussions that discourages participation is having too many people discussing together. In a class of 60, you don’t expect everyone to talk in a class discussion. Having 60 people in an online discussion becomes chaotic quickly. The Groups tool in Canvas (located inside the People tool) allows you to assign students to smaller groups for discussion. Breaking students up into smaller discussion groups, either randomly or by interest area, can produce better dialogue. Group size for discussions where students are asked to reply and converse with their peers can range from 5 (in a graduate class) up to around 15 (for a larger undergraduate class).

Click on the headings below for specific recommendations.

Have complete and accurate instructions and criteria

It’s not uncommon for students to give up on discussions (and other assignments) because the instructions for the task aren’t clear or haven’t been updated for changes in other places. This includes clear instructions for both their initial participation and the following discussion.

Having someone else proof instructions before sharing them with your class can catch simple typos that can change the meaning of a sentence. If you are sending your students to look at a website or use a tool, always double-check those instructions every semester to make sure your links are still good, and that other aspects such as menus, page names, or functionality haven’t changed. If students go to an external site expecting to click on a specific thing when they get there, and that thing is missing, it can stop them in their tracks. Don’t presume that they will search extensively for the missing thing – or that they even have enough information to know what they are searching for, depending on the detail of instructions provided.

Make sure you also provide clear criteria for success. Remember from the TILT model that the criteria are not the same as the task. Unless you are grading complete/incomplete, there will be some level of quality included in the criteria. The criteria should let the student know what your expectations are for successful work beyond following the basic instructions.

Encourage students to reflect on learning from discussions

It’s not uncommon for students to dislike discussions and other collaborative activities because they feel that they don’t learn anything from them. By sharing your desired learning outcome with your students, you can then ask them to consider the extent to which they reached that learning outcome and what part of the activity helped them. This is something that you can do for all assignments and activities, not just discussions.

You can use an anonymous survey in Canvas or Qualtrics to get feedback to improve any following discussions and address misconceptions about learning by means other than reading and lecture. Keep in mind that a reluctance to learn from and with peers can be a cultural issue. Some educational systems focus on learning only from the teacher, and interaction with peers is not highly valued. It helps to be prepared to explain why you value discussion and student-student interaction in both online and in-person classes.

When Discussion Goes Bad: Conflict in an Online Course

Conflict—whether overt or covert—is something no one enjoys dealing with in the classroom. In a face-to-face class, you may be able to quell inappropriate behavior with a sharp look or a word of warning after class. In an online class, inappropriate behavior may be harder to spot and harder to combat due to the text-based nature of most communication. Managing Controversy in the Online Classroom (a Faculty Focus article) provides an overview of proactive and reactive ways to avoid controversy and handle it when it does appear.

To avoid conflict that stems from incivility, beginning with Core Rules of Netiquette is a good place to start. Reminding everyone that there is another human being on the receiving end of each message can help students calibrate their reactions to the context. Asking students to participate in discussions by posting video comments also reinforces the reality that they are talking to other real people. Mintu-Wimsatt, Kernek, and Lozada (2010) suggested a list of netiquette items for a graduate online class which includes:

- Do not dominate any discussion.

- Never make fun of someone’s ability to read or write, especially when English is a second or third language.

- Use correct spelling, grammar, and plain English.

- Keep an open mind and be willing to express even your minority opinion.

- Think before you push the “Send” button.

- Do not hesitate to ask for feedback.

When conflict occurs, Horton (2006) recommends some options for instructors:

- If you have taught the course before, you may be able to anticipate problems and have a consistent, thought-out response ready.

- Include netiquette requirements in the syllabus and course introduction. Many learners may not know the conventions and expectations for online learning. Enforce policies consistently.

- When you come across unacceptable behavior, do not respond without taking a moment to think about the behavior in context. For example, if students are experiencing frustration with the course or the tools, respond to both the usability issue and the way they expressed it.

- Differentiate between first-time violators and serious or repeat offenders. What can be used as a learning experience versus what requires disciplinary action?

- Help students learn to disagree professionally and politely. If they are used to the sort of disagreement and “debate” that occurs on social media, instructions and modeling appropriate ways to give and respond to legitimate criticism may be helpful.