9 Flicka

Flicka thought she was people. She was a person like you and me.” The people who raised her treated her that way. As a colt, she would go into the house and eat “people” food. She thought the children were her peers and, as she grew, her physical dominance manifested as a spoiled brat. She became temperamental and even bullied the children. She must have thought she was something regal, and we should have named her Pegasus!

I was with Dad one day in 1951 when we stopped by the small farm on the edge of Berthoud, Colorado, to collect the hay we had been providing all winter. Instead, the man offered Flicka the $25 payment instead of Flicka. The responsibility and expense for Flicka had become a liability, and it was time for them to part.

“Dad, did we just buy a horse?” The excited 7-year-old me just had to know.

“Yes, I did.”

“That will give us two horses, then! When will you bring her home? Can I ride her?”

“No, you can’t ride her yet, she’s not broke.’ She’s a colt and we must wait until she is ready. We can start halter-breaking her now and get her used to having a saddle on her back. In a few months, when she becomes a two-year-old, we will begin teaching her to ride.”

The next Monday, when the school bus dropped me off at home, the corral had a new tenant. The reddish-colored sorrel Flicka was in the corral with the gray Tuffy. (A few years earlier, a Wyoming Rancher had given Tuffy to us when he began to slow down and could not continue separating the calves from their mothers. He was very safe as a kid horse.)

Tuffy was a good horse for learning to ride. My sisters and I sitting in the saddle. Photo by Jean H. Bein, 1949

There was an uneasy standoff as the two horses struggled to decide a pecking order. There were a few well-placed kicks and some sharp bites. The old, retired cutting horse had little time for foolishness and soon took command. “Such an indignity! That old horse just pushes me around.” Flicka learned quickly whom she had to respect.

From left to right: Tuffy, Flicka, and Kit. Photo by Rick Bein, 1953

As I walked up to the corral, Flicka ran over to me. “Here is one of those nice people who treat me right and let me do what I want to do.” I stroked her forehead, and she nuzzled my hand. I left her and went off to change clothes to begin my chores. Stepping back out of the house, Flicka whinnied at me across the farmyard. “She is really friendly,” I thought. “I never knew a horse to be so happy to see me.” I began to love her.

As we got to know Flicka, we learned that she loved human attention and she would eat anything that we ate, except for meat and apples. Meat was understandable. But, apples! Well, we learned in time that if we peeled them first, she would enjoy them very much.

Once, when one of my school friends came out to the farm, we went out to see the horses. We went into the corral and started stroking her when my mother came out and brought us each an ice cream cone. As we began enjoying this treat, Flicka, feeling left out, walked up to Danny Schreiner and reached for his ice cream cone! Danny backed away until he came to the fence, where Flicka pinned him with her chest. Danny extended his ice cream cone behind him over the fence to keep it away from the horse. But to no avail, as Flicka’s neck and head were longer than Danny’s arm. Flicka plucked the treat out of his hand, and in one gulp, it disappeared! She did not even have a brain freeze! Danny sadly went without his ice cream. She then went after mine, but I jumped the fence where she could not reach it.

Eating around Flicka meant we had to be ready to share.

Flicka always watched what we did, and she learned how we opened the latch on the gate to the corral. One morning, as we started out the back door, we found her inside the porch of the house. She had even managed to open the screen door after climbing up the concrete steps. She wanted to be people.

Horses and cows

Two milk cows were kept in the same corral with our horses. This was not the most ideal situation for the cows because the horses enjoyed dominating them. Tuffy taught Flicka how to “cut”; that was what cutting horses were trained to do on the ranch when it was necessary to sort cattle. Cutting was essential to separate the cows from the calves at weaning time, and Tuffy still had enough agility to keep the two milk cows apart.

The cows were milked in the barn next to the corral, and Flicka enjoyed standing with her head in the door watching the hand-milking. A dozen cats would join us, as they opportunistically licked up any milk that missed the pail. It was fun to aim a teat at one of the cats and extrude a full stream of milk its way. The cat would try to catch all of the milk in its mouth, usually getting more on its face and fur. Flicka did not respond in the same way. When we poured some milk into the cat pan on the floor, she extended her nose, shoved all the cats away, and in one slurp sucked up all the milk!

We later had to separate the cows from the horses, because Flicka learned that she could nurse the cows. It took us a while to figure out why the cows were suddenly giving significantly less milk. Then one day, we saw Flicka trap one of the cows against the fence and reach down to the cow’s udder and gently start nursing. I could imagine that ol’ cow thinking, “My, what’s this world coming to?”

Training of Flicka

Flicka enjoyed her lks with us when we put a halter on her and began teaching her to lead. Initially, I think that she thought that she was leading us, because she would always try to walk out ahead. She had a mind of her own and tried to go where she wanted. As a seven-year-old, I was too small to control her, and it was difficult to take her somewhere that she did not want to go. Dad had greater success with her and taught her to follow. He spent several days a week working with her, getting her used to a bridal bit in her mouth and a saddle strapped to her back. As Dad trained her, she learned to be a follower, and I was able to lead her, so after school, I took over some of the daily routine.

One day, when the bus dropped me off, I learned that there had been an accident and the doctor had to come out to the farm to treat my six-year-old sister Jeanie.

Dad had thought that Flicka was safe enough to place my sister Jeanie in the saddle while he led the horse around. He suddenly swooped Jeanie up and placed her on Flicka’s bare back. It was safe for Flicka, but not for my sister. This was the first time a human had been on her back, and Flicka decided that this was another indignity; she leaped off the ground, bucking Jeanie high in the air to come straight down on her chin on the gravel driveway. Jeanie’s wind had been knocked out of her.

This had a serious impact on my sister, who for years would never go near Flicka. Flicka would chase and bite and kick Jeanie if she went into the corral. This event was also a turning point in Flicka’s relationship with humans. She decided that humans were not her best friends anymore. It became obvious that she was a temperamental horse around whom we had to always be on guard for some kind of mischief.

Dad continued to break her and, to her ultimate disgust, taught her to ride. She never did become a safe horse to be around, and she took to biting and kicking people. She refused to stand still when a rider tried to mount her, and it took someone with a lot of horse savvy to ride her. She would jump sideways from the rider when any weight was put in the left stirrup, making it a challenge to throw the right leg over her back. She shied at anything, and a rider had to constantly be alert or he would soon be lying on the ground. Dad was the only one to ride her for several years.

A difficult horse

As the years went by, I began to ride her. It was a scary experience at first, but it taught me to be constantly vigilant of her antics. Soon, I learned her bad habits and could anticipate her next move. It improved my riding skills. To keep her from jumping away from me when I went to mount her, I learned to stand her next to a fence, so there was nowhere to jump. Once on her back, I was pretty much in control. We rarely let anyone else ride her.

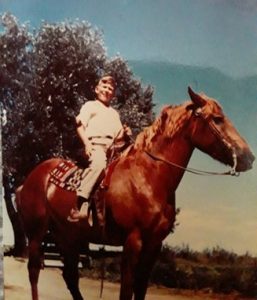

Twelve-year-old Rick Bein, riding Flicka. Photo by Jean H. Bein, 1955.

Twelve-year-old Rick Bein, riding Flicka. Photo by Jean H. Bein, 1955.

One time, I did let Danny ride her. I was riding Tuffy, and we had been out riding for an hour and had started home. As we came within sight of the farmhouse, the horses turned barn hungry and suddenly, without warning, took off at a full gallop. I got Tuffy under control and looked ahead to see how Danny was managing with Flicka. All I could see was Flicka running at full speed with an empty saddle. Danny had disappeared! I looked back to see if he had fallen off, but he was not on the ground. Then I noticed some human feet swinging out to Flicka’s side. The lurch of the horse had thrown Danny forward, and as he sailed out of the saddle, he was able to get both hands around Flicka’s neck. Somehow, his body rotated under the horse’s neck, and there he was, suspended in front of the galloping Flicka!

The extra weight on her neck did not seem to bother her, because she galloped even faster as I tried to bring Tuffy alongside so I could reach over and grab her reins. Old Tuffy was not able to catch up. Somehow, Danny managed to hang on that last half mile, all the way to the barn, where she stopped, and Danny just dropped his feet to the ground. I always wondered if Flicka had a stiff neck for a few days, not to mention Danny’s sore arms!

Flicka was a large, strong horse, probably a cross between a quarter horse and some kind of draft horse. I could ride her for hours without her getting tired; I would tire first.

Flicka was also ticklish. She did not like to have her legs or underside touched in any way, and when it happened, she would scream and lash out with a bite or a kick. This made it difficult to trim her hooves, or for that matter, to connect the saddle cinch under her girth.

Once she got tangled in barbed wire. I rode her up next to a barbed wire fence and stopped to look at something on the other side of the fence. Standing still was not one of her favorite things, and she continued to prance around. In the twisting and turning, she stuck one of her feet over the lower strand of wire. When she pulled back, the barbed wire stretched toward her and frightened her. She panicked and tried to run away. The strand of wire held her foot, and the barbs began to cut her. In the process, the other front hoof became caught in the barbed wire. Then, in her panic, she pulled the strand of wire loose from the fence and began dragging it toward her. In the struggle that ensued, I was thrown clear. As she fought with the wire, it cut deep wounds into her legs. I tried to grab her reins and control her. That seemed to make things worse. All I could do was to let her wear herself out, and after a few minutes of thrashing around, she fell to the ground and, in her exhaustion, lay still for a moment. I was able to slip up and pull the wire loose; that motion startled her again, and up she jumped to escape the devilish wire!

She was a mess! Her front legs were lacerated in some places down to the bone. I could not ride her, so I led her the half mile back to her corral. When Dad came home, he called the vet. Flicka was in bandages for months after that. Her ticklish nature made it difficult to change her bandages. Compounded with her wounds, she was even more ticklish.

My sister had a similar experience with Tuffy as she narrates this story.

“When I was seven, I used to take gentle Tuffy for long rides. This time, I only went about two miles to our Hilltop farm as I wanted to swim in the water hole there. I dismounted in the farmyard and tied Tuffy to a clothes line, as there were no fences. The clothes line frightened him, and he panicked. The large, strong horse bolted, pulled the clothes line poles over with the terrifying lines flapping around his head. He ran into me and knocked me over, hitting my head on the ground, stepping heavily on my right thigh, and my lower left abdomen. I lost consciousness for a little while. When I came to, Tuffy was calmly eating grass nearby with his bit in his mouth. I found that I could stand, with pain. I realized that my choices were limited: I could stay there and wait forever for someone to find me, or I could try to walk home, though I was sure I couldn’t make it. So I walked slowly up to Tuffy. My injuries did not allow me to mount him from the ground. I led him to a wooden gate, and he somehow climbed the gate and got on his back. He walked home very slowly. I slid off at a fence and went inside and to bed. Tuffy waited at the barn uneventfully. Mom called Dr. Arndt, who soon made a house call. No bones were broken, nor did my gut rupture, just soft tissue damage and later a lot of scar tissue which has plagued me to this day.”

Taffy

Old Tuffy finally died. He was in his late twenties and had become slower and slower. The ten years of his retirement had been spent taking care of children, exercising the milk cows (until Flicka discovered cow’s milk), and on occasion, helping us drive a few cattle between pastures. He was missed.

Dad bought Taffy, a Palomino quarter horse, from a family friend. He had belonged to Tommy Greenly, who had trained him, and as a youth spent many hours wandering around the foothills of the Rockies. But Tommy grew up and began his career, which did not allow much time with his horse. When he heard that Tuffy had died, Tommy offered to sell Taffy to us as he had decided that we were the kind of family with whom he could entrust his childhood friend. Tommy had trained Taffy well. Taffy was very smart and knew how to handle many situations. Nothing startled him, and he was also good with children.

I learned that horses and people bond. In addition to this, there is a healing relationship that a horse empowers by sensing what kind of emotions the human is experiencing, a sort of therapy that the horse provides with its calmness. I had not thought of that, but now that you mention it, it’s true.

Competitions

When I was about 12, my sister Jeanie and I began entering the horses in skill contests. These were the tame rodeo activities like barrel racing and pole bending. We entered a lot of events not knowing what was required.

We thought Taffy and Flicka were pretty fast runners, and we ought to enter them in the half-mile race. Jeanie rode Taffy, and I rode Flicka. When we arrived at the track, all the other kids who entered this race were dressed up like jockeys and were riding thoroughbreds with English saddles. They looked pretty serious. At the gun, they were serious! We were left in a cloud of dust and flying mud. There was no contest as we were so far behind; the judges did not even think we were in the same race! They were already lining up the horses for the next race when we finally arrived at the finish line. One official yelled, “We need you off the track so we can start the next race!” I was too embarrassed to tell him that we were still trying to complete the previous one!

Another timed competition event was the “keyhole race”. One at a time, the contestants raced their horses into a keyhole that had been drawn with lime on the arena floor. Once inside, the rider would turn his horse around and race back to the finish line. It was a competition based on speed and agility without disturbing any of the lime markers on the ground. There were two keyholes so that two horses could be competing at the same time.

I ran Flicka up to the keyhole, slowly entered, and carefully turned her around without stepping on the white lime markers. Our time was very slow as the best riders were able to race in and out of the keyhole in a few seconds. When it was Taffy’s turn, he grabbed the bit in his mouth and decided to do it alone without Jeanie’s guidance. Unfortunately, he headed for the wrong keyhole and stomped all over the white lines. Of course, Jeanie and Taffy were disqualified, but the performance was humorous and resulted in some laughter from the audience. Jeanie was mortified!

Jeanie was further distressed when I, the big brother, chose to take Taffy for the next event for which she was registered. I decided that Taffy would have a better chance than Flicka in the “trail horse” competition, and I did not trust Jeanie’s ability to control Taffy. I did not know exactly what the event looked like, but I knew it was some kind of obstacle course that required a calm horse, undeterred by noises and fences. Taffy was the best of our two horses. Many of those kids with the thoroughbreds from the half-mile race that morning had also entered, and I thought, “Oh, oh, this is going to be another embarrassing moment!” A few of them remembered me, and I got some weird looks.

I soon discovered that this event challenged the horse and rider, who took turns opening gates, stepping over logs, walking through a creaky wooden chute, climbing over a huge pile of old tires, and dragging a burlap bag of noisy empty cans. Fortunately, speed was not an issue. “Bein,” being near the beginning of the alphabet, Taffy and I went early. Taffy acted like this was nothing special and took the course as if it were something he did every day. He even made it look boring compared to the high-strung thoroughbreds that bolted with each new obstacle.

After all the horse and rider teams had gone through the course, all contestants stood in a long row facing the judges. They began calling up each team one at a time in reverse order of performance to give everyone a ribbon of recognition. I expected that we would be called up very soon. Team after team was called up, and still, we were not called. “Had they forgotten us again?”

Much to my surprise, as it came down to the last few teams, Taffy and I were still standing there! “Maybe we are going to win this!”

I had watched the other horse and rider teams take their turns, and I saw demonstrations of good riding. I thought, “Surely one of those kids with a thoroughbred would win this competition.” But that was not what the competition was about. It had more emphasis on the horse’s ability to negotiate each new mini-adventure along the trail with the guidance of the rider. Well, at this point it all became obvious! Taffy won the trophy! “Tommy Greenly, you done well!”

Motherhood

Doctor Tramp in Loveland had a pure-bred Arabian stallion, which he offered free stud services for kids with 4-H horse projects. I had to ride Flicka the 10 miles up to the north side of Loveland for her to be bred. Ten months later, Flicka gave birth to Hadje.

Flick and newborn Hadje. Photo by Rick Bein, 1956.

Flick and newborn Hadje. Photo by Rick Bein, 1956.

At first, Flicka was a little confused with this offspring that kept nuzzling her in her ticklish spots. She kept squealing and kicking every time the colt tried to nurse. It was a little disconcerting, as we thought that Hadje was going to starve. We went to bed that night, not knowing if the colt was going to live. I guess nature took over, because in the morning, Hadje was nursing normally, and Flicka had accepted motherhood.

Flicka’s life changed again as she assumed responsibility for the colt. She was very protective, and when I rode her, Hadje was allowed to run free alongside. I had to stay off the highways because Hadje had no fear of cars, and we were afraid that he would step out in front of fast-moving vehicles. Fortunately, that never happened.

We raised Hadje as a horse, not as a human. He was halter-broken by the time he was one year old. Dad made sure that he was used to us touching and handling his legs so that he would not become ticklish like his mother. Dad overdid it when he tried to force Hadje to lift his leg by pulling it up with a rope draped over the horse’s back. It caused Hadje to fall and somehow injure his leg, causing him to become slightly lame.

Pinned by a horse

Flicka was biting and kicking at me! She did not like that I was sitting on her two-year-old colt, who was trapped on his back in the feed-bunk. It did not matter to her that I was also trapped with one leg pinned under the 500-pound colt. Her posturing was a mere annoyance compared to the excruciating pain in my leg!

I was 15. It was late December, and I was in the process of breaking a two-year-old Hadje to ride. I had never been on him before, but I had halter broken him, and he was used to having a saddle on his back.

On one sunny post-Christmas day, I decided he was ready for me to ride. I put the saddle on him and led him out into a recently plowed field where the soil was soft, and would provide a soft cushion if Hadje were to throw me off!

I led him out about fifteen yards into the field and put my foot into the stirrup, and swung onto the saddle. Bracing for Hadje to begin bucking and surging, I was ready. Surprisingly, nothing happened! He stood trembling as if not knowing what to do. He did not move a hair. I waited several minutes quietly sitting, while we stood motionless.

After ten minutes or so, I began to coax him into moving a little. Finally, I jumped off and led him a few steps. He followed. On his back again, he would not move. Finally, I goaded him more violently, and he took a few steps. Slowly, we proceeded toward the corrals. After about an hour, we finally arrived outside the pen where Flicka, his mother, had been frantically whinnying the whole time. She was angry with me and ran back and forth inside the corral, baring her teeth and kicking her back feet toward me. Still, Hadje didn’t want to move very much and just stood beside the cattle feed bunk that extended along the outside of the fence.

Suddenly, after standing parallel to the fence for about five minutes, Hadje leaned sideways toward the corral as if to get closer to his mother, lost his balance, and fell into the feed bunk. His legs shot sideways as his body tumbled over the side into the feed bunk. Sensing too late what was happening, I pushed away from the top of the fence with my hand and jumped partially free so that my full body was not trapped under the horse. But I was unable to escape completely; my left leg was trapped in the feed bunk as the horse fell into it. I found myself sitting on Hadje’s stomach with my leg rapped beneath him, the weight of the horse resting on my lower leg.

Hadje could only move his head and feet. Fortunately, he just lay on his back and relaxed. Had he been of a more nervous temperament, he could have thrashed around and kicked me. Who knows what kind of damage he might have caused!

The pain was severe, and I was sure that my leg was broken. I sat there screaming, but it did no good. The tree trimmers were in the front yard about 100 yards away, and their chainsaws drowned out any noise I could make. For a moment, I pounded on Hadje’s chest with my fists. That didn’t help, and fortunately, it did not upset him and cause him to kick me to pieces. I realized soon enough that my predicament could become a lot worse if this horse were to become agitated.

My thoughts went to Flicka, who, in her fury, continued biting and kicking at me from inside the fence. As it was, the threat that she presented was only minor compared to the pain that I was experiencing! For the most part, I gave her little attention, and eventually she seemed to calm down. Hadje could do nothing… I could do nothing.

I looked around for help. There was no one in sight. I called out, but the tree trimmers’ saws drowned me out. I was out of sight of the house, so my mother and my siblings were unable to see me.

This was one time when all I could do was call on a higher power. In my agony, between my tears, I prayed. That seemed to numb the pain. All I could do was wait. Many thoughts came to my mind; somehow, I knew that I would survive this, but with what impairment, I did not know. I thought about the coming weekend when I was to play in the Junior High School basketball game. That brought me some sadness, as surely my broken leg would put me out for the season.

I had no sense of time, and after what seemed to be many hours (probably about one hour), Gramps, the elderly father of the tenant who farmed our place, drove up in his pickup truck. My prayers had been answered!

He quickly saw my predicament and grabbed a fence rail that was lying nearby and wedged it under the horse’s flank, and began to lever it upward. Just as the weight of the horse was off my leg and the pain began to subside, the rail broke and the horse came crashing down on my leg again.

Gramps realized this was a job for more than one person and went for help. At least I knew that this odyssey was almost over. He sounded the alarm. I still had to wait, and the pain seemed to be getting worse. I had little patience when Cathy, my six-year-old sister, came running up. I must have looked rather strange to her as she asked, “Ricky, what are you doing to that horse?” Poor girl; in my agony, I unloaded a rich vocabulary of words that she probably had never heard before. Despite all that, in her childhood wisdom, she went back to the house and got help.

The tree trimmers came and wedged the horse up to free my leg. I was free! My leg was not broken. It was only sore for a few days, and I still played in the basketball game that weekend. I don’t remember who we played or who won, but I do remember this experience!

Gramps finally came back with the front-end loader tractor and slipped a chain under Hadje and lifted him out of the feed bunk. The horse was OK, and his mother was relieved.

Hadje developed a habit of expanding his lungs when he was being saddled, keeping the cinch loose when he exhaled. As I mounted him, the saddle rotated with my weight, and I had to re-tighten the cinch. After that, I would remember to wait five minutes after initially tightening the cinch to tighten it again. That worked, but I am not sure if I had warned anyone about his habit. Several years after I left home, my mother attempted to ride him. After she mounted, Hadje let out his breath, and the saddle rotated sideways, dumping Mom to the ground. As fate would have it, her foot was still in the stirrup, and Hadje panicked, dragging and stepping on her. Mom had to go to the hospital and spent several months convalescing.

Ben

Dr. Tramp’s offer was still there, and we had Flicka bred again. Ben was a sorrel, like his mother. His older brother Hadje was a roan whose color faded to gray after a few years. Ben was a bit more spirited than Hadje, but a lot easier to handle than his mother. He became bigger and stronger than Hadje. After I had broken him, he became a good horse to ride for the intermediate-skilled rider. Beginners could start with Taffy or Hadje.

“Filho da Puta”

I never gave a proper name to the horse that I had in my Brazilian Peace Corps days (1964-66 Pedro Gomes, Mato Grosso, Brazil, but since that was what Milton called him, I decided it was appropriate. The Peace Corps would not allow me to have a motorized vehicle at my work site, and since I was an agricultural extensionist, I needed transportation out to the farms. I tried a bicycle, but it was limited to the dirt roads, and someone stole my bike anyway! The Peace Corps ageed to buy me a horse.

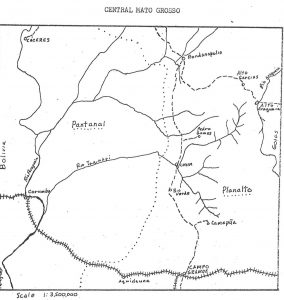

My Peace Corps site, Pedro Gomes, is near the center of the map. Hand-drawn map by Rick Bein, 1966.

Milton, one of the shopkeepers in Pedro Gomes, had a difficult horse that he wanted to sell. He said the horse was too unruly for him, and he had been trying to sell it for some time. That sort of spurred my interest, and Milton took me out to his nearby pasture to see the horse.

The horse walked up to us to eat the grain that we offered. Milton quickly placed a bridal over the horse’s head, and we went over to a shed to get a saddle. Once the horse was ready, Milton suggested that I go ahead and try him out.

Milton held the horse’s head while I began to mount, but out of some stroke of meanness, decided to strike the horse hard on the nose just as my leg started to swing over the horse’s back. The horse bolted, of course, but thanks to those years of riding Flicka, I managed to finish mounting and gain control of the horse. I also managed to keep my temper with Milton, who just grinned at me. I rode the horse around the pasture to find that he was not well-trained and was skittish! I knew he would take some work.

I saw the horse as a challenge and agreed to buy it if Milton would let me use his pasture and would buy the horse back for the same price when my tour in the Peace Corps was over. The double-digit inflation of the Cruzeiro made this profitable for Milton.

Filho da Puta was another Flicka, but much more skittish and would shy away at anything that moved. Some of the townsmen took derisive pleasure in suddenly throwing their arms in the air when I would ride up. This would cause the horse to bolt, and I would have to regain control. This made me angry at first, but I realized that this was a bit of their culture. I put a stop to it when I invited a few of these keesters to ride the horse. When one of them finally accepted my offer, he did not last long in the saddle. Because I was the only one who could ride him, I gained the reputation of being “um bom cavaleiro.”

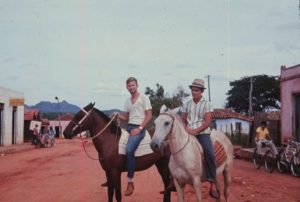

Bugre and I with our horses on the main street of Pedro Gomes, Mato Grosso, Photo by Rick Bein 1965

Filho da Puta became attached to me, and he decided that he liked going places became easier to catch in the pasture. He was a very strong horse with lots of endurance. Once we were out away from the town, we made good time.

One rancher invited me to his distant ranch, forty miles away. His son and I spent the night on the trail. After a few days out there, I headed back into Pedro Gomes. I made it in one day! This horse was not even tired, as he began acting up as usual when we finally neared town.

Motorized vehicles

Motorized vehicles terrified him, Filho da Puta, who would go into a panic, becoming very hard to control. Fortunately, very few vehicles made it to Pedro Gomes. However, there was one occasion that I remember well. I was going to a farm and was following the gravel road that connected Pedro Gomes with the outside world. A four-wheel drive diesel approached us. I looked for a place to take the horse off the road, but the sides were too steep and there was no escape route. I decided I would try to control him anyway and moved him to the side of the road so the vehicle could pass. That did not work!

Filho da Puta bolted, lunging and spinning! He slipped in the loose gravel, trapped my right leg beneath him, and fell on his side onto the ground. My right leg was trapped beneath him! He kept kicking and trying to get up, but could not do so as long as my other leg was on top of him. I was afraid to move that leg because I couldn’t see if my trapped foot was stuck in the stirrup. If that were the case, the horse could drag me to death in its panicked state!

After what seemed an eternity, I realized that I had to decide as the kicking horse began to tear up its legs in the loose road gravel. I decided that if I let him up, I would keep hold of the reins and would have a better chance of maintaining control. I took the chance, and when he did jump up, I found my foot was free, so I was able to hold onto the reins and angle my body so that, in his panic, he pulled me to my feet! He was forced to run backwards as I controlled his head with the reins. I talked to him and gradually he calmed down.

The driver of the vehicle had turned off his engine and came over to see if I was all right. He explained that he was planning to shoot the horse and then pull it off me, but everything happened so fast, and now I was free and the horse under control. My hard-toed boot had spared me any injury to my foot. He apologized for causing any problem. I explained that the problem was the horse, not his driving.

Breaking lines

Filho da Puta developed a bad habit of breaking his lines whenever he was tied up. He would do this by sitting back until his weight would break whatever was holding him. He was always getting loose, either breaking his halter or his lines.

Later, the very same day that Filho da Puta had fallen on the road, I stopped at a rancher’s home to take a rest from riding. There was a stout-looking hitching post in the middle of a corral where I tied him. I used the new halter and rope that I had just bought, hoping that he would not be able to break it.

I went inside to enjoy a cup of coffee and a little conversation. That did not last long as someone came running in yelling, “Tem uma problema com seu cavallo!” (Something is wrong with your horse!)

Filho da Puta had tried his favorite stunt of leaning back to stretch the lines until they broke. Well, the rope was strong, and it did not break, but that fifty-pound hitching post came right out of the ground and went right for the horse! What terror he must have experienced! Filho da Puta ran away with the six-foot post following him! When he saw the post coming at him, he dodged to the side, and the post sailed past his head. The post would go as far as the rope would allow and then be pulled back to go after the fleeing horse again. The horse soon found himself backing in circles, with the flying post orbiting around him!

The lady of the house came out and started screaming, “Santa Catarina, Santa Catarina, Santa Catarina!” This endless litany to her patron saint filled the air, only to be disturbed by the sound of the log bumping into the sides of the corral. The situation was completely out of control. I wanted to try to stop the panic, but there was no way I could approach without being clobbered by that flying log! I had to wait until the horse wore himself out.

He kept dodging the heavy post until the corral fence got in the way and there was no place to escape. “Clump!” The log crashed into the horse. Off, the horse charged again, this time rotating the post in a counterclockwise direction. On one of the collisions with the post, it bounced off the back of the horse and came down on his other side, the rope winding over his neck. This shortened the distance between the horse and the post, and it became harder to dodge.

The log socked the horse more frequently, and the rope wrapped around his neck again and again until finally, it was so short that the log hung right against his ear. There was no escaping now; the post was virtually attached to his head. The weight of the post now bore down on his head, and he finally accepted that escape was impossible, and he stood exhausted for a moment. There was my chance. I reached over with the lady’s kitchen knife and cut the rope. As the log hit the ground, the horse lunged away again; finally, Filho da Puta was “free of that monster-post!”

Before it was over, the post probably hit every part of that horse’s body. Riding back into town that day, Filho da Puta was the calmest I had ever seen him. He was exhausted. He did not shy away from anything. The adventures of that day were enough without him creating any more.

When I finished my tour in the Peace Corps, Milton was happy to buy the horse back from me and was even happier now that Filho da Puta was much more manageable.

When I got back to the States, I realized that my adventures with horses were over. Dad had sold all the horses, and I went off to finish my bachelor’s degree at the University of Colorado.