59 BIO-DIVERSITY INVENTORY OF KAMIALI WILDLIFE MANAGEMENT AREA

Rick Bein

THE BIO-DIVERSITY INVENTORY: CASE STUDY OF KAMIALI WILDLIFE MANAGEMENT AREA

F.L. (Rick Bein

Environmental Research & Management Centre

PNG University of Technology

Lae Papua New Guinea

Location of Papua New Guinea 1________500 miles Map for the Village Development Trust by CIA.

Location of Papua New Guinea 1________500 miles Map for the Village Development Trust by CIA.

Abstract

A team of scientists in 1997-98 inventoried the biodiversity of the Kamiali Wild Life Management Area, 60 kilometers southeast along the Huon Gulf coast from Lae, Papua New Guinea. The 434 square kilometers area was registered with the PNG government as a wildlife management area in 1996. A village of 500 people has elected a committee who with the Village Development Trust, a Nationally based NGO, manage the area extending 12 kilometers out to sea and 17 kilometers inland. The high relief environment ranges from 1080 meters below the sea up to 2012 meters above mean sea level. A transect method was used to sample biomes beginning with open sea, coral reef, mangrove, beech, village, sago swamp, garden, riparian environments, tropical forest and cloud forest. This study provides a baseline inventory for a unique area which has never experienced hillside gardening nor commercial logging and contains a high biomass environment that serves as a habitat for many rare species. This case study demonstrates an application for the conservation of natural Resources for Science and Technology in Development.

The Role of Conservation and the Wildlife Management area

“Conservation of resources” is a concept which lies half way on the continuum between ”exploitation of resources” and “preservation of resources”. Resources exploitation is the extraction of nature in a manner in which there is no regard for the long term future benefits that those resources may provide for humans. The antithesis of exploitation is the preservation of resources which in the pure sense promotes the total non-use of the resources by humans. Neither of these extreme approaches can functionally serve human kind for the long term. Humans must use the earth’s resources in order to survive and conversely, humans will perish if they the consume all of the resources at once. Conservation on the other hand promotes the sustainable use of natural resources.

Wildlife Management Areas (WMA’s) have been established for years in a number of countries (including Papua New Guinea) to slow down the process of exploitation of natural resources. It falls slightly left of center on the preservation side of the continuum. Another concept, the Integrated Conservation and Development Area (ICAD) is a recent addition to the many methods of protecting the natural environment from human destruction. It promotes sustainable human use of the resource and occupies a more central position. In PNG, WMA’s have been more commonly established because there are government regulations to follow. Regulations for the implementation of ICADs did not exist in PNG until recently. In many situations the WMA’s of PNG are now including the thinking behind the ICADs by incorporating the concept of “sustainable use of resources”. This is the current position of the Kamiali Wildlife Management Area (KWMA).

“Conservation” is quite different from “preservation” which promotes total disuse of the environment by humans. Although the idea of preservation has merit in small isolated parts of the earth, it is largely impracticable with growing populations and their increasing demands on the natural resources. Conservation on the other hand takes the position, “That if humans are to survive on this planet they must strive to find sustainable uses of the environment”. Should people fail to do this they will perish. The planet has been around for a very long time and it will continue to be around for a very long time. The question is: “Will people continue to be along for the ride?”

Conservation of biodiversity

Biological diversity is the richness of our planetary ecosystem and includes genetic diversity, species diversity and ecological diversity.[1] The conservation of the biodiversity is important not only to ensure survival of millions of species but also to support the living systems of the world’s people who depend on natural resources and the ecosystem. Leading ecological thinking considers high bio-diversity to be a desirable thing for the planetary ecosystem. Following the ecological premise that every living thing has a “niche” or functional purpose in serving the greater ecosystem, it would hold that by maximizing the number of living species, there would be more opportunities to maintain ecological balances. As a part of the global ecosystem, humans would benefit the most from high biodiversity. Benefits found in nature take the form of foods, medicine, building and clothing materials and chemical substances. Many discoveries have benefited human kind and have over the millennia fostered the expansion the earth’s human population. Maintaining bio-diversity provides continuous human benefit. Preserving bio-diversity does not contradict conservation; conservation when operating properly preserves bio-diversity.

It further happens that tropical biomes such as those in PNG contain some of the highest bio-diversity on the planet. Hundreds of species, many yet to be named, thrive in the PNG rain forests and coral reefs. The world is eager to discover these new species, their ecological niches and the benefit they can provide human kind. PNG is still 60% forested[2] much of which is pristine and contains some of the richest biodiversity in the world. There is great fear that PNG will lose this resource if current trends of deforestation continue.

Dichotomy between economic development and Conservation

Papua New Guinea, on the other hand, is striving to develop economically and coupled with a 30 year population doubling rate it must exploit its basic resources. Traditional paradigms, (or ways of thinking) and lifestyles of the village are changing. Attitude toward the environment is also changing. Western paradigms, promoting the monetary economy begin to erode the old lifestyles, and the environment becomes expendable for the purpose of seeking immediate wealth. During a paradigm shift the natural environment becomes vulnerable and easily exploited to support the new way of thinking. Exploitation occurs during the transition when old thinking gives way to, or merges with new thinking.

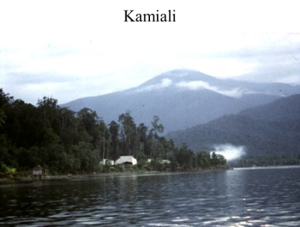

Blue Mountain stands over the Kamiali landscape, and the Village Development Trust facility for visiting scientists (white building). Photo by Rick Bein

Application to Kamiali

Kamiali became a WMA because of several unique circumstances:

1) it is the only coastal village along the Huon Gulf between Lae and Oro Province which chose not to sell their trees to the Malaysian logging companies during the early 1990’s and

2) the food garden soils in the fertile Bitoi River flood plain provide enough food that there has been no need to clear the highly erodible hill sides.

As a result of these two factors, much of the forest remains pristine, and the coral reefs fringing the coast of Kamiali are equally pristine because they are free from the smothering effect of sediments eroding from the land.

Since Kamiali is mainly a fishing village, there is very little hunting pressure and the original wildlife is intact. The three village hunters have had little problem finding wild game with in short distances of the village and as a result rarely venture up into the remote areas generally above 300 meters elevation.

Village Meeting: VDT representative addresses Kamiali villagers Photo by Rick Bein

Village Meeting: VDT representative addresses Kamiali villagers Photo by Rick Bein

Methodology and Logistics

The biodiversity inventory was conducted during the period between July 1997 and July 1998. When the Lababia community established the Kamiali Wildlife Management Area, the Village Development Trust of Lae, PNG, obtained a grant from the New Zealand High Commission to conduct this study. The grant provided for the listing of species found in the various biomes through out the Wildlife Management Area and the listing recommendations regarding further study and better conservation of the wildlife management area. The sampling technique comprised a transect from the open sea through the coral reef, mangrove swamp, beach, freshwater mangrove, sago swamp, lowland rainforest, lowland hill forest, upland and montane cloud and moss forest. Also sampled were sites that the scientists deemed to be notably different such as Lababia Island and the Bitoi food gardens. No attempt was made to numerically quantify any part of biodiversity except in the case of the fish study. Nor was there any attempt to sample the genetic diversity.

A signed “scientist, good faith, research agreement” has been established to provide incentive for the villagers to host scientific research and to protect their intellectual property rights. This includes an understanding that participating scientists:

1) build into their research proposals, cash grants as contributions to the community,

2) employ villagers when ever possible in the data collection and educate them within their desire to understand about the research and its methodology in order to strengthen their abilities and enthusiasm to support future research, and

3) commit to share the proceeds, should the scientist or representative institution make a profit from the discoveries at Kamiali, as a continuing contribution designated to support village causes such as the payment of school fees or for the purchase environmental conservation technology.

Facilities to accommodate field research scientists include the comforts of a guest house with prepared meals, and a training center built by the Village Development Trust, air compressor to refill diving tanks, storage capability, easy access to most biome areas, transect trails to the more remote environments, and boat transportation from Lae. Up to 16 people can be accommodated in four person screened bunk houses and another 20 people in a dormitory bunk room. Running water supplies clean showers and toilet

Preliminary results

Thirteen participating scientists focusing on different parts of the biota have found many unique aspects of the bio-diversity of the Kamiali area. Briefly, the high lights of the findings show that:

1) the fringing coral reef is one of the highest biomass reefs in Papua New Guinea,

2) the undisturbed lowland hill forests next to the ocean shoreline are unique because they have not been periodically cleared for food gardening like most PNG coastal communities,

3) vegetation typical of 2000 meters elevation is found as low as 600 meters on ridge slopes facing toward the sea,

4) a vast area of land has not been untouched by humans for at least the last 50 years,

5) Lababia Island serves a major roosting site for frigate birds and pied imperial pigeons,

6) the broad sand beaches of Kamiali are major nesting sites for leather back turtles, and

7) several undescribed insect species are in the process of being recorded.

The complete inventory contains the appended reports of each scientist including all species found and those species, not seen, but which are probably there because of their association with other known species. Also included are recommendations made by the scientists for maintaining the biodiversity and for future research.

Arial view of Kamiali Village Photo from Village Development Trust collection.

Arial view of Kamiali Village Photo from Village Development Trust collection.

A base for further research

The biodiversity inventory at Kamiali with its logistical facilities in place provides an excellent basis for further research. The potential for future research in such a pristine environment is unending. The major difficulty is the long distance travel and time required to come to Kamiali from the research institutions around the world.

This inventory is not all inclusive as the sampling technique used could only probe a small area. There are great research possibilities in the further sampling of the biomes. The cloud forest biome has been barely examined for plants and insects. The coral reefs and mangroves and beech areas offer many opportunities. Over 100 leather back turtles nested in Kamiali this last season and discussions are underway to experiment by incubating some of the eggs to ensure greater hatch rates.