76 Urban Farming in Indianapolis

Rick Bein

Urban Farming in Indianapolis by Rick Bein, Bhuwan Thapa, Jeff Wilson

Urban agriculture is the practice of cultivating vegetables in or around urban areas. Besides horticultural products, urban agriculture involves animal husbandry, beekeeping, aquaculture, and agroforestry. Increasing urbanization coupled with the challenges of sustainable development in cities have contributed to a growing interest among urban agriculture researchers, policy makers, and stakeholders (Siegner et al., 2018). Growing prevalence of urban agriculture represents a resurgence of vegetable growing where there is a popular dimension of contributing to a greater cause. The chicness of gardening provides opportunities to serve preferences for local produce. Urban Agriculture is also being explored as a strategy to address issues of food insecurity, income inequality and health disparities. Gardening is considered an option to remedy the urban food deserts where there are no grocery stores within a one-mile radius. The myriad potential health & social benefits while maintaining a watch out for toxic air and legacy contaminants in soils.

History of urban agriculture in Indianapolis

Urban agriculture has been a part of the landscape of Indianapolis begun in the 1840s (Jo Ellen Meyers Sharp, 2019). German immigrants brought with them their greenhouse technology and developed numerous urban farms on the south side of the city. From that time, they provided a significant supply of the city’s vegetable needs until the 1970’s. Year-round production was made possible by heating the greenhouses in the winter using mostly coal as fuel. Diminishing evidence of these old greenhouses (Figure 1) can still be found on the south side of the city, in particular along Bluff Road, W. Washington and Rockville Rd. This area was once a hub of vegetable production in Indianapolis. The Indiana Historical Bureau placed an official state historical marker honoring the early German gardeners in Bluff Road Park at Bluff Rd & Hanna Ave. (Sharp 2019)

Figure 1. Remains of a 1950’s greenhouse and smokestack of a coal fired furnace. Photo by Rick Bein 2020.

With construction of the interstate highway system in the 1960’s, many changes to the American landscapes occurred. The Census of Agriculture shows a drastic decline of farmland in Marion County from 58 percent of the county to 23 percent in 1978 and 2.9 percent in 2012 (1). Much of the decline in local vegetable production in Indianapolis diminished drastically with the growth of the interstate highway system enabling refrigerated trucks to bring fresh vegetables in two days from frost free areas in California, Florida, and Texas. As transportation and refrigerated shipping became more efficient, the cost of produce imported from out of state became less than those of the Indianapolis producers who had to bear the cost of heating greenhouses. Gradually, the local vegetable production in Indianapolis was reduced to a few specialty vegetables like herbs and spices.

Indianapolis has experienced a resurgence in the last 10 years for commercial, community, not for profit and institutional gardens (United States Census Bureau). This resurgence in Indianapolis is due to several factors. New low-cost technologies of wind and solar energy and high-capacity batteries has made it possible to provide the necessary heating of greenhouses and plastic hoop towers. With electricity becoming cheaper, greenhouses are more efficient, and an expansion of garden technology has led to increasing local production.

The dormant green thumb is emerging within the county. Community gardening in neighborhoods when vacant land becomes available, and groups of local residents who combine their efforts to begin raising vegetables. Most of these are “home consumption” arrangements that provide food for families. Institutional gardens are sponsored by churches, schools, hospitals and city government and donate produce to food pantries or donate directly to needy families. This aspect has been brought about by Indianapolis City government’s support of not-for-profit gardening with land and “startup grants.” Grants from businesses and industrial groups have supported the continuation not-for-profit and community gardens. The Purdue agricultural extension program has made a major encouragement effort by educating growers, proving technical assistance and gardening supplies. Other attributes for gardening include environmental conservation, minor reduction of the urban heat island effect, educational purposes at schools, social cohesion of neighborhoods, biodiversity enhancement when combined with bee keeping, and soil health enhancement with earthworm compost.

The Geography Department at Indiana University Purdue University at Indianapolis (IUPUI) launched a study of the spatial aspects of urban vegetable gardening in Marion County with the support of the Purdue Agriculture Extension Service and the Indianapolis Department of Community Nutrition and Food Policy program.

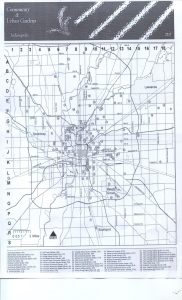

Two student assistants funded by a grant from the IUPUI Center for Service and Learning helped to conduct interviews and organize the responses. AmeriCorps volunteer, Skylar Roeff, assigned to the Indianapolis Department of Community Nutrition and Food Policy contributed greatly to completing a master list started by the Marion County Office of Sustainability. The list was further expanded by contacting other partner agencies like Purdue Extension, Indy Food Council, and browsing through various websites. About 100 gardens were contacted for interviews (Figure 2). On-site and telephone interviews were conducted with the gardeners. The data was made available to the City of Indianapolis for planning purposes.

Figure 2: Inventory map of Urban Gardens was developed by the Indianapolis Office of Sustainability 2019.

The survey provided a variety of garden types detailing the purpose for individual gardens, size, type of vegetables grown, and who consumes the produce. Here, differences are highlighted with examples. Private home gardens, although quite prevalent, were not included in this study.

Neighborhood community gardens occur where land is available in back yards or empty lots. They are frequently located in food deserts where there are no grocery stores within a mile. Most neighborhood gardens are organized by one individual who invites others in the vicinity to participate. Raised garden beds are allocated to interested families who may pay a token ($12) to manage and grow what they want for their own consumption. Figure 3 shows James Whitfield (far right) who maintains a neighborhood garden with raised beds shown behind on the ground. Located in a food desert on the near North side of Indianapolis, people generally grow tomatoes, collards, lettuce, and legumes. Serving the people of the neighborhood is the main mission. The major challenge for success depends on one person to carry out the organization, registration, and recruitment of participants. If the lead gardener leaves, there is no one to take over. Water during dry spells is also a challenge. Expensive household tap water is frequently used for irrigation.

Figure 3. Service-Learning assistant, Sneh Shah (middle) interviewing community garden leader, James Whitfield, and his neighbor. Photo by Rick Bein 2018.

Registered Community Gardens are organized with a network of gardeners who share information, conduct workshops and present seminars for anyone who wants to participate. Workshops include food preparation and diet balancing as well as gardening techniques. They also lease out raised beds to landless urbanites. Mixed cropping enables a wide variety of vegetables to be produced. The workshops provide information about pest control, mulching of soil, and companion planting.

Sharrona Moore (Figure 4) found that planting garlic between the broccoli plants kept pests like rabbits, deer and some insects away. She also gives seminars on food preparation and conducts tours. Lawrence Community Gardens is a 7.6-acre garden located on 46th Street, just east of Post Road. They partner with Monarch Beverage, located at 9347 Pendleton Pike, and the City of Lawrence to grow produce that is donated to the neighborhood Cupboard and Sharing Place food pantries. Monarch Beverage allows their unused land to grow these vegetables. The missions to promote community and environmental sustainability align perfectly.

Figure 4. Sharrona Moore, Lawrence Community Garden. Photo by Rick Bein 2019.

Figure 5: Carina McDowell, Sugar Grove community Gardeners. Photo by Angela Campbell

Carina McDowell has a good set up with lots of options on-site. They have a tool shed and a makeshift seating area. The mission is to expand food gardening in the neighborhood. Carina is exasperated by the lack of the participation from the community and the discontinuation of funding from the city. She said the Mayor’s Action Committee helped with the first year, but nothing after. Challenges are the lack of participation, lack of parking, pests like rabbits and deer and an abundance of mosquitoes. They have a large variety of crops and are exploring ways to cut costs and be more environmentally aware.

Church sponsored community gardens are managed by interested members of the congregations to provide vegetables to needy families.

Figure 6: St. Joan of Arc Garden, Winter season. Photo by Rick Bein 2019

Figure 6: St. Joan of Arc Garden, Winter season. Photo by Rick Bein 2019

Behind St. Joan of Arc Church A garden with raised beds waits for spring planting. A member of the church oversees the operation and recruits parishioners to participate. Challenges include a shortage of labor, weeds and expensive city tap water.

Figure 7: Burmese Gardens at the 1st Baptist Church. Crops are mixed randomly amongst each other. Note the fence made of fallen sticks from the nearby woods and the plastic bags to frighten away birds. Photo by Rick Bein 2019.

On the property of the First Baptist Church twenty families of Burmese refugees grow vegetables much in the way they are grown in Myanmar. Their Garden is primarily for home consumption, but it provides an activity for their senior citizens of the community with productive activity. The Burmese Garden is quite unique as the gardeners use local materials from the wooded areas such as vines and fallen branches to fashion fences. They also practice multicultural cropping by planting different vegetables side by side allowing ecological relationships where plants support each other in various ways. This includes exotic vegetables only known in Southeast Asia. Expensive tap water is provided by the church.

Gardens at schools are quite common which add hands-on activity learning to the curriculum as well as education about aspects of growing, maintaining, and harvesting plants. Many schools in Indianapolis have some form of a garden, only for educational purposes where the children are involved with the gardening processes. These range from a single “raised bed” on a playground to a fully operational greenhouse. At Orchard Elementary School, Vicki Prusinski directs student gardening activities throughout the year in the greenhouse and in a plastic hoop tower. Maple trees on one acre are producing sap (Figure 10) that the children collect and learn how to make maple syrup. The big challenge is timing class activities around the seasons and the weather. There are no students to participate during the summer growing season.

Figure 8: Buckets are place low enough so Orchard Elementary students can collect the sap and learn to make maple syrup. Photo by Rick Bein, 2019.

Figure 8: Buckets are place low enough so Orchard Elementary students can collect the sap and learn to make maple syrup. Photo by Rick Bein, 2019.

Some hospitals maintain community gardens for their recovering patients who participate in the planting and weeding and in turn benefit from learning food preparation. The Eskinazi Hospital Corporation includes gardens at their neighborhood clinics (Figure 11). Besides health care, their mission is multifaceted, education being first while community interaction and community cohesiveness come second. Many of their patients live close enough that they continue to return to work in the garden after their hospital stay. This contributes to substantial neighborhood camaraderie as well as a healthier diet.

Figure 9: Service-learning assistant Angela Campbell interviews the hospital “green” garden coach at the Brehob Community Center. Figure 10: Sky Garden on the roof of Eskinazi Hospital over looks downtown Indianapolis and Campus Housing. Photos by Rick Bein.

Eskinazi Sky Farm located on the roof of the Eskinazi Hospital is supported by the Eskinazi Grant Foundation. It has become part of the healing environment of the Eskinazi Hospital on downtown campus, The Sky Farm has 5,000 square feet of growing space dedicated to 25 – 30 different crops and flowers. The initial planting began in the spring of 2014, just after the Sidney & Lois Eskenazi Hospital opened. Rachel White directs all the garden activities.Education is the main mission providing classes for university dietician program, hospital patients and students. Group tours include elementary school classes. Volunteer groups, mostly students, also enjoy the fresh food. Hospital employees enjoy coffee breaks and the opportunity to meditate. Sky Farm is open to the public from February to November, 24-7. Occasionally it is closed for private events. To access The Sky Farm, take the Green Elevators in the Sidney & Lois Eskenazi Hospital to the seventh floor.

Gardening is done on raised beds using composting with plant material. Plantings include 60 varieties of vegetables but mainly Kale, Collards, tomatoes, and Carrots. “Sedum” is used as a ground cover during the off season while the plots wait to be cultivated. Black plastic cover surrounds the plants for weed control. Worm castings, compost from coffee grounds, fish emulsions and pulverized eggshells provide fertilization. Neem oil is used for pest control. A beehive provides pollination. The main challenge is the expense of water. Since its beginning the harvest has increased every year.. In 2019 more than 3,000 pounds of produce was harvested. Projections for 2020 indicate there will be 3,700 pounds of produce.

Local government organizations are sponsoring gardens to support their food pantries. Indianapolis Park Service supports several not-for-profit garden projects around the city. Marion County Soil and Water Conservation Service uses the Indy Urban-Acres Garden (Figure 11) as a demonstration site for proper soil and water management. Indy Urban Acres’ main mission is to donate vegetables to needy families. Grocery sized bags are being sent to over 300 families at Senior Citizen communities, Eskinazi Clinics, Glick owned apartment complexes and the Old Bethel Food Pantry. The Garden director Tyler Gough has acquired numerous grants mainly from the Glick Family Foundation, and from the Indianapolis Pacers and Eskinazi Grant Foundation. Indy Urban Acres cultivates 8 acres producing over 30,000 Pounds of vegetables per year. About 40 different vegetables are grown.

The Indianapolis Parks has set aside a five-acre site on West Tibbs Street (Figure 12) where residents can rent a ¼ acre garden area. The main mission is to provide food for home for consumption. A tractor operator contracts with each gardener (farmer) to prepare the soil for planting. The “Mayor’s Garden” has one challenge and that is to provide water for irrigation during dry spells.

Figure 12: The Mayor’s Garden” supervised by Indianapolis Parks provides nearby residents with quarter acres to produce vegetables for home consumption. A custom tractor operator prepares soil. The city charges the gardeners $20 per year for five acres. Photos by Rick Bein 2019.

A few “for-profit-gardens” operate in the county. Most of them compete with gardeners from neighboring counties to sell their vegetables at the “Farmers Markets” in Indianapolis. Many of these gardeners have developed online marketing strategies and deliveries. Frequently purchases are made over the telephone or online and the food is picked up by the consumers at the farmers’ markets.

Danny Garcia of Garcia’s gardens, (Figure 13) surrounds his house, backyard, and a next-door lot with a total 1.2 acres of vegetables. A green house, several hoop structures, numerous raised beds, open soils plots and a compost pile are included. He supports himself completely by selling mostly at farmers markets. He takes online orders and by phone for pick up and deliver to buyers.

Figure 13: Danny Garcia, owner of Garcia’s gardens, manages one acre that surround his home with raised beds, greenhouses, and plastic hoop gardens to raise vegetables for sale at numerous farmers markets. His Farmers’ market booth is located at the Broad Ripple farmer’s market. Photo by Rick Bein 2019.

Founded in 2016, “CRG Grow” is the Cunningham Restaurant Group’s own greenhouse. The hydroponic greenhouse provides the opportunity to control produce options and quality. Safe growing practices, organic pest treatments, no harsh chemicals, and purified water ensure the produce provided is sustainable,, safe and fresh for the CRG restaurants. The quarter-acre green house in downtown Indianapolis supplies vegetables to seven restaurants. This electronic facility (Figure 14) includes climate control and water distribution on demand. Organic Peat soil provides a solid growing base. The produce grown at CRG Grow includes basil, mint, thyme, various micro-greens, tomatoes, and peppers. Prior to the Covid 19 pandemic, four employees were required to coordinate supplying vegetables to the scattered restaurants.

Figure 15: Cunningham Restaurant Group’s massive greenhouse operates in a downtown Indianapolis building using solar energy for lighting, climate control and irrigation. Diners in 7 mid-western restaurants enjoy the vegetables. Photos by Rick Bein, 2018.

Why hasn’t large scale vegetable production caught on with the large commercial farms in Indiana? These farms already have a niche in the national economy of industrial agriculture that grow a high tech genetically modified crops. Corn is made into glucose and soybeans are exported overseas. This allows the urban garden phenomenon to fill the empty niche and flourish.

This study looks at the variations in the services that gardens provide according to the institutional categories. These services are measured in terms of production, educational services, and social interactions. The institutional categories include for-profit farms, non-profit farms, educational gardens, and community gardens. This study offers much “food” for thought