48 From the Sahara to North Dakota

After two years in the Sudan, we thought it was time to come back to the States. I wanted to continue my university geography career so the break would come at the end of academic calendar in May. Early in 1976 I began looking for university positions. Communication from the States was slow, six weeks for a letter to arrive, but deadlines were already passed. Not knowing what to do, it was easy to stay, particularly with the welcoming nature of the Sudanese and the University of Khartoum. I also needed to complete some research projects. So, we happily stayed, and the University instead, gave us home leave to visit the States.

Map of Nile up to Khartoum by Chris Lett, July 2019, Creative Commons Licensing Chris Lett.

Since only two round-trip tickets were provided, I chose to remain and let Mary and the twins go. That gave me some distracted time to work on my projects. It might have been advantageous to return and begin looking for jobs beginning in 1977. Nevertheless, I used the time productively and traveled extensively in Sudan. I explored Darfur in the west, Dongola in the North, and many communities to the South: Geneina, Nuba Mountains and Eastern Equatoria.

When Mary and the twins returned to Khartoum in 1976, we decided that we wanted another child but not by cesarean birth as would be required in the States. (The twins were born cesarean in 1972.) The current medical practice in the US dictated that “once a cesarean, always a cesarean.” This was not the practice in Khartoum. We found a Sudanese obstetrician who confirmed this. We decided to proceed.

Khartoum January 1977. Photo by Rick Bein.

The timing to return to the States in the summer 1977 was going to be necessary since the twins would be ready for Kindergarten in the Fall and there was no kindergarten in the Sudan except for the expensive private American School. The cost equaled my entire salary.

The 1976-77 year went well, my research progressed, and Leila was born in May. I realized that I would have to return to the States without a job. We knew we could stay with my parents while I looked for an academic position. So off we went to Colorado to prepare for our next adventure.

Sudan and the rest of the world. Map by whereismap.net

Sudan and the rest of the world. Map by whereismap.net

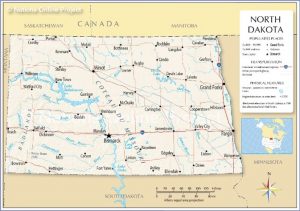

I applied at a number of universities and got an offer to come to the University of North Dakota for one year. Arriving there in August, the Department chair, William A Dando warmly welcomed me, and I dove into my teaching assignments. Bill Dando also offered to review my research writings and pushed me to write more. With his tutelage, I wrote eight papers on the Geography of Sudan, published three of them, and became involved with the professional geography societies of the States. I owe a debt of gratitude for this man’s support. This was a lifesaver for me as my improved academic credentials provided a strengthened application for university positions for the fall of 1978. Although it was late in the year for the academic recruitment, I was asked to interview at four universities and was offered the position at IUPUI which I happily accepted and taught forty years.

https://www.nationsonline.org/oneworld/map/USA/north_dakota_map.htm

Meanwhile the North Dakota experience was a story all by itself. I had forgotten what cold winter in the States was all about. The pleasant weather of August and September preceded a frigid challenge! Everything froze solid on the first of November and thawed out in April. The change from the 105-degree weather of the Sudan was in stark contrast to the minus 20 degrees of the Dakotas. We survived! People helped us out and guided us in our adjustment.

The locals never batted an eye with the cold. Houses were built with thick insulated walls. The warm parkas and face masks did their job. We learned to walk on ice and snow and discovered that our car would freeze up in spite of the antifreeze. Electric block heaters that plugged into an attachment on the car engine were located at every house. Fortunately, the locals prepared us for these hazards. We learned cross country skiing and did a lot of ice skating. We foolishly ventured off through a blizzard to spend Christmas in Colorado with our folks, drove through a blinding snowstorm and plowed through four-foot snow drifts, but luckily made it without any mishaps.

North Dakota was the land of wheat, soybeans, canola, barley. sunflowers, and potatoes. Corn and sugar beets were grown in the east. Further west it was dry, where they grew sorghum, flax, and rye. Irrigation supported these crops. Otherwise, cattle grazing prevailed. It was said that there were two cows for every human in the state of North Dakota. There were fewer than eight hundred thousand people in the whole State, less than the city of Indianapolis,

Photo by Rick Bein 1978

Photo by Rick Bein 1978

The remoteness of Grand Forks, North Dakota was such that the nearest big city was not Minneapolis but Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada. We went shopping in Winnipeg 2 or 3 time during the year. The University of North Dakota was in Grand Forks, on the other side of the Red River from Minnesota. Out of state tuition was waived for students from the surrounding Minnesota counties.

We enjoyed North Dakota until June 1978 and moved to Indianapolis where the weather was more welcoming, and the professional opportunity was greater. And that is another story.