15 The Peace Corps Experience

My Peace Corps Beginnings

Following a couple of less than mediocre years in college, I was at a loss as to what was next for me. My father’s friend, Dr. Stonaker from the School of Agriculture at Colorado State University suggested that I apply for the Peace Corps. It did not matter that I had only two years of college, because Peace Corps was looking for volunteers with agricultural experience and there were not many in the United States.

I grew up working with livestock on our farm in Berthoud Colorado. Photo by Rick Bein 1964.

I grew up working with livestock on our farm in Berthoud Colorado. Photo by Rick Bein 1964.

I applied and within six weeks I was given an invitation to start training in August of 1964 to work in Brazil. I was elated! This was an adventure! This seemed like a dream. I was both terrified and eager for this adventure. I boarded my first airplane in my life in Denver and flew to Milwaukee to begin the training. I was 20 years old and open to whatever was to come. Sitting next to me was a fellow passenger in her mid-30s with whom I began a conversation and opened a rather spiritual philosophical discussion that put me at ease with whatever would happen. She explained how each stage in my life was meant to prepare me for the next. My fear dissipated.

I took that “open” attitude with me and met the Peace Corps representative at the Milwaukee Airport who took me and several other volunteers to the University of Wisconsin- Milwaukee (UWM) campus. There we were housed with several groups training to serve in Brazil. I was included with a group of young farm kids, ranging in age between 18 and 24. We bonded rather quickly as we progressed through the program. The intensity of our relationships were strengthened as we lived together, cared for each other, studied together speculated as to what the trainers were thinking about each of us and which of us would be deselected and sent home. That was a rather fearful time as we did not know what defects they were looking for.

There must have been some kind of psychological evaluation going on to determine if we were in the right frame of mind for the Peace Corps and to represent the United States. We were never certain how they were evaluating us, but after 6 weeks on the training about half-a-dozen of our young farmer group suddenly disappeared. We were told they were deemed unsatisfactory for the Peace Corps. Unfortunately, we did not expect this and had not exchanged addresses and phone numbers from any of them. To this day, I don’t know the rest of their history. A similar event occurred 3 days before the end of the program when a few others were deselected.

The training was made up of a lot of classes in Portuguese and lectures on Brazil, Peace Corps principles, tropical agriculture and medical awareness issues. Most of our time was engaged with learning Portuguese, which included considerable time repeating Portuguese phrases and words into tape recorders. Each of us had a head set from which we could listen and then repeat. Our instructors would randomly listen to each of us as we repeated what we heard and correct us on the spot. I think growing up around Spanish speakers in Colorado gave me some advantage. A Mexican American family, the Huertas, babysat me when I was 3 to 5 years of age, and I must have absorbed a lot of what was being said. Spanish is very similar to Portuguese as two-thirds of the Spanish words are the same. I had also taken Spanish in high school and college. Whatever the case, I did well learning Portuguese which now dominates my Spanish.

We finished the training about mid-November, arriving in Rio de Janeiro on the 22nd of November 1964. one year to the date after President John Kennedy was assassinated. Many Brazilians were still seething about the assassination and challenged any American who they think might be a fugitive by asking “Where we you at this time last year? Did you have anything to do with Kennedy’s death?”

Pau de Acucar (Sugar Loaf, top). Street view from Hotel Florida. Favella under an over pass. Photos of Rio de Janeiro by Rick Bein 1964.

Rio was a huge adventure in itself. We were housed in the Florida Hotel, a rather modest facility in the Botofogo neighborhood. While in Rio we completed paperwork, visited the American embassy, met the American ambassador and the Peace Corps director for Brazil. Here we learned that we were to be stationed in the State of Mato Grosso rather than the northeast where we were originally to be located. Castelo Branco, the Military dictator who had just overthrown the socialist democratically elected president, Joao Gularte, was not quite sure about this strange “Peace Corps” that he inherited. He decided to let it continue because it was sponsored by the United States and that relationship was important. However, he had his doubts about what it might do, he decided to locate us out in the Brazilian frontier where we would do less harm.

Within a few days after arrival in Rio, we were flown to Campo Grande in the Frontier State of Mato Grosso to celebrate the American “thanksgiving holiday” at the home of Gene Jefferies, Assistant State Peace Corps director. There we met another contingent of Peace Corps volunteers who preceded us by two months.

Each of us was assigned to one these earlier arrivals to accompany them at their work sites. I joined Richard Bartels who was being assigned to the town of Rio Verde do Mato Grosso.

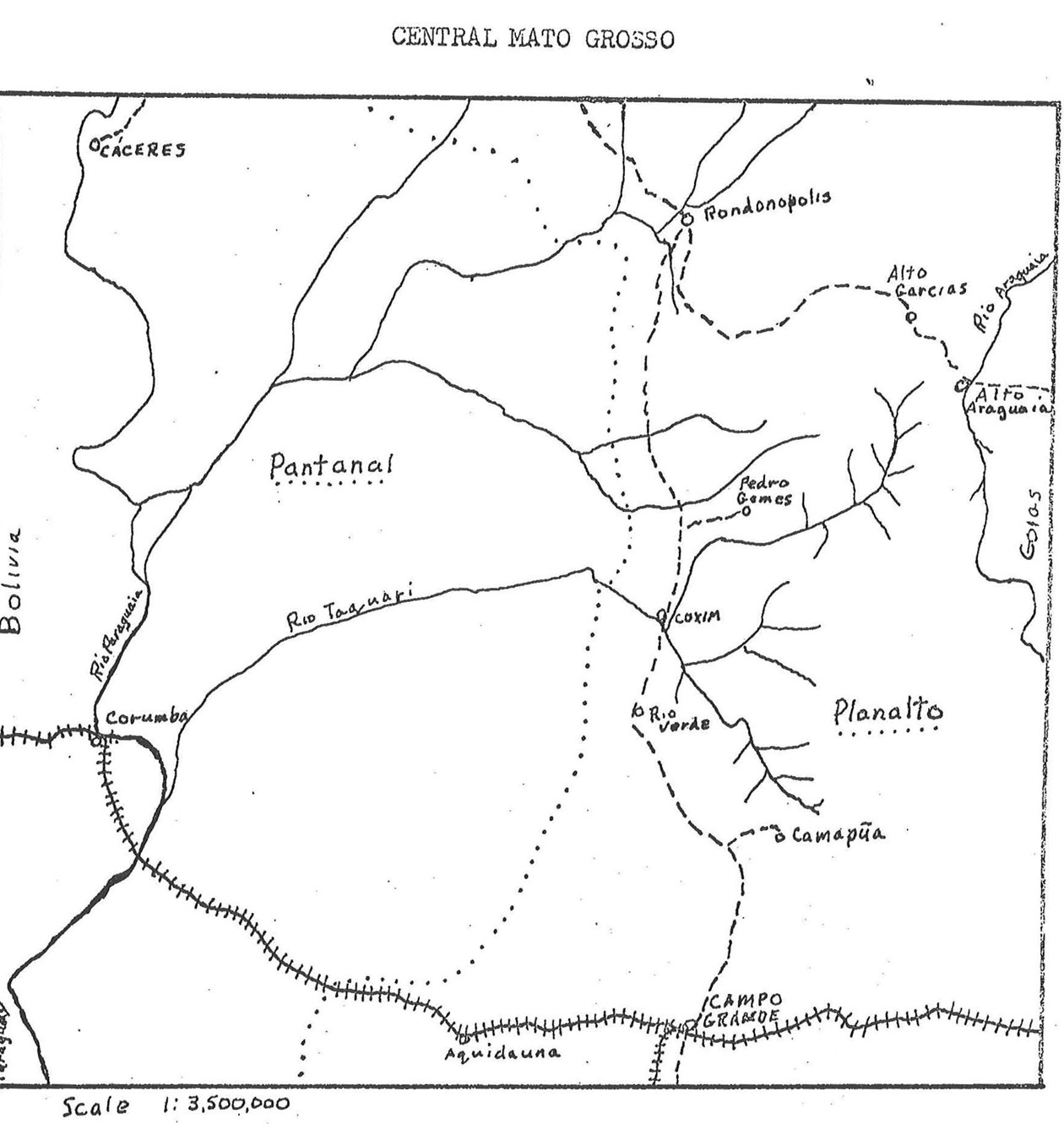

My hand-drawn 1965 map of the central Mato Grosso region that includes Campo Grande with the road leading north toward Cuiaba the Mato Grosso State capital passing through Rio Verde, Coxim and Pedro Gomes. I worked in Rio Verde for 6 weeks and the rest of my stay was in Pedro Gomes.

In Rio Verde we experienced a number of adventures (see “Butcher” and “Piranha” stories). We became comfortable in the local pensão (boarding house) and were welcomed by the community leaders. We made many friends there who were then disappointed when I was reassigned to Pedro Gomes, two hours to the north. One consolation was that I would be frequently visiting Rio Verde on the way to our headquarter city, Campo Grande.

Arriving in Pedro Gomes I joined my Brazilian counterpart, Antonio Francisco dos Santos, also an agricultural extension agent. He had a little shop called the Casa de Lavora (house of crops) in the middle of the short main street where we interacted with farmers when they came to town.

Antonio roomed at the Pensão Barbosa where I shared his room for a few months. Later I found a small house to rent with a hand drawn well and an outhouse. I still took my meals at the pensão.

Approach to Pedro Gomes. Photo by Rick Bein 1964. .

Approach to Pedro Gomes. Photo by Rick Bein 1964. .

Pedro Gomes was originally called “Amarra Cabelo” (hair tying) a name that the early Portuguese explorers gave it when they came across indigenous women tying up their hair in the small creek. (The indigenous people were either assimilated or driven away by the arriving Brazilian settlers). Some of the locals claimed some indigenous roots, but could not relate much about that time period. This place grew from a few houses into a pioneer town that was named Pedro Gomes after one of the settlers.

Most of the inhabitants were migrants from the impoverished Northeast of Brazil who came to improve their lives in the far western part of the country. They practiced “Slash and burn” subsistence agriculture where the natural vegetation was burned and then planted with upland rice and beans. “Slash and burn” involved cutting and burning the natural vegetation and planting crops in the fertilizing ashes. After a few years, the ashes were used up and the soil worn out. The farmer having no chemical fertilizer, moved on, cutting and burning another area. The forest regenerated over a period of time and eventually would be cut and farmed again.

Archedorio’s harvested upland rice stacked, waiting to be threshed. Photo by Rick Bein 1965.

Archedorio’s harvested upland rice stacked, waiting to be threshed. Photo by Rick Bein 1965.

The natural vegetation is mostly savanna with a dry season and a rainy season. Rather than a grassland, the Brazilian savanna is a low scrub forest called “campo cerrado” which takes up a significant part of Brazil. The campo cerrado is an edaphic vegetation that depends on a dry season fire every few years enabling for seeds to germinate and grow. This soil is not a very fertile.

Farmers prefer to cultivate what they call mato (closed canopy forest) that grows on terra preta (dark) soils which occur in low lying areas that have more available nutrients. These darker soil pockets yield better crops and are highly sought after. These terra preta soils occur in odd spots throughout the Brazilian Plateau including the rainforest areas. In the savanna where there is source of water like a flood plain or high water table, a more luxuriant mato forest is also sustained throughout the six-month dry season. These soils are also sought after for cultivation.

This tropical forest was set on fire during the dry season in preparation for planting in the rainy season. The nutrients from the ashes sustain crops for about three years, then it is left to fallow. Photo by Rick Bein 1971.

Burnt forest. Plantings are interspersed between charred logs. As firewood and charcoal are collected more crops are planted. Photo by Rick Bein 1971.

Burnt forest. Plantings are interspersed between charred logs. As firewood and charcoal are collected more crops are planted. Photo by Rick Bein 1971.

Rainforest clearings taken by Author flying over the Amazon in 1988. A recent burn, center right appears dark, a recently abandoned farm appears on the left, short recovering forests at top, and bottom right shows virgin rainforest. Photo by Rick Bein 1988.

Rainforest clearings taken by Author flying over the Amazon in 1988. A recent burn, center right appears dark, a recently abandoned farm appears on the left, short recovering forests at top, and bottom right shows virgin rainforest. Photo by Rick Bein 1988.

Leaf-cutter ants (formigas saúvas) find open areas in the forest such as where trees have fallen and build in sunny spots in the ground. At the same time they try to keep the clearing open by cutting the green vegetation. This cut vegetation is carried into the burrows and allowed to mold. The mold is eaten by their larva.

Normally the forest regenerates faster than the ants can keep it open and the colony is forced to move to another clearing. In this manner the leaf-cutter ant is kept at homeostasis. But when the ants find a clearing that a shifting cultivator has created, there are no trees to control them and their population explodes thriving on the tender crops. The farmer sometimes has to move even before the soils wear out.

Leaf cutter ants (saúvas) carrying crop leaves to their burrow in the forest. Photo by Rick Bein. 1971.

Leaf cutter ants (saúvas) carrying crop leaves to their burrow in the forest. Photo by Rick Bein. 1971.

One pesticide called “Aldrin” was somewhat effective in controlling the leaf cutter ants. At the Casa de Lavora we sold more of this item than anything else and the State Ministry of Agriculture, to whom we answered, subsidized the cost of Aldrin. In the 1960’s there was no awareness of the high toxicity of this chemical which has been found to pollute drinking water. At that time, we thought of it as a wonderful solution. Now in the 21st century it is still being used in Brazil. In the small population in Mato Grosso we observed no health problems but apparently in the more populated areas of Brazil it has become serious.

Another factor that disrupted the small shifting cultivator has been the introduction of African grasses which have no natural predators in Brazil. These grasses including Colonhao, Jaguar, and Pangola among others, are excellent food for cattle, but they have out-competed the natural grasses and invaded the small farm clearings that the shifting cultivators have temporarily abandoned. By the second and third year of cultivation these exotics begin crowding out the food crops. A farmer said to me “Fighting the grasses is harder work than burning new forest”. Another farmer told me it is much easier to clear forest, immediately plant grasses and start a small herd of cattle.

Abandoned farm home with invading African Jaraguai grass. Once the invasive grasses take over, the land becomes a permanent pasture. Photo by Rick Bein 1971.

Abandoned farm home with invading African Jaraguai grass. Once the invasive grasses take over, the land becomes a permanent pasture. Photo by Rick Bein 1971.

Blowing the berrante calls the cattle to come and get some salt, a rare element in the rainy tropics. The zebu cattle, originally from India, survive in the tropics better than do the European breeds. Photo by Rick Bein 1965.

Blowing the berrante calls the cattle to come and get some salt, a rare element in the rainy tropics. The zebu cattle, originally from India, survive in the tropics better than do the European breeds. Photo by Rick Bein 1965.

This invasion of exotic grasses has played into the hands of the cattle ranchers who find pasture lands appearing where the farmers have abandoned their farms. I heard it said that ranchers, who would like to shorten the small farmer cropping period, have seeded grasses in these small farms. Furthermore, these grasses are encouraged by intermittent burning. Once the grasses become started it very hard for the forest to get a foot hold due to the periodic burning. Logging and Industrial Mining also contribute some additional deforestation. Gradually a forest region ends up as a tropical grassland.

These observations come from the 1960’s and now, 55 years later, the process is still continuing. Mato Grosso do Sul is almost all pasture land and now produces most of the beef eaten in the rest of Brazil. This process is now also happening in the Amazon basin which is seriously threatened.

Looking at the other vegetation type in Pedro Gomes, the campo cerrado, previously considered to be a rather useless resource, recently has gone through a major metamorphosis. Through entrepreneurial efforts soybeans are found to grow well during six-month rainy season. Soybeans only need a few months of rainy weather which matches well in the climate of this unique savanna land. Heavy applications of fertilizers have overcome the lack of nutrients in the soil. Mechanized soybean farming has become a major industry in Brazil and is competing with the United States.

While I was in the Peace Corps, the Mato Grosso State Ministry of Agriculture sent small packets of the soybeans to the volunteers to pass out to farmers. We took part in this successful endeavor by introducing a brand-new crop to Brazil. Little did we know of what would develop? In honoring Brazil for its resourcefulness, there is a downside as the campo cerrado is now becoming endangered. This brings to mind what the North Americans did with their native prairies.

Back to Peace Corps Activities

As agricultural extensionist, Antonio and I visited farms, performed minor veterinary procedures, found shop owners to distribute cotton seeds, and started a 4H (4S in Brazil) club where we taught young teenage boys how grow vegetables. The Peace Corps office sent us the seeds. They also sent a projector along with a series of films promoting healthy practices.

Preparing a vegetable garden bed with 4S (4H) boys. Photo by Antonio Francisco dos Santos 1965.

Preparing a vegetable garden bed with 4S (4H) boys. Photo by Antonio Francisco dos Santos 1965.

When the State Board of Health sent a shipment of smallpox vaccine to the mayor of Pedro Gomes it was decided that Antonio and I were the best ones to vaccinate those people who volunteer to be immunized.

The Ministry of Agriculture asked me to find a responsible shop owner to provide the infrastructure to distribute cotton seeds to farmers and facilitate the shipment of the harvested cotton to the market. He contacted many of the farmers who had migrated from the Northeast of Brazil who were already familiar with cotton farming. Production happened immediately. This cotton farming expansion extended north from Pedro Gomes into what is now the State of Mato Gross, which fifty-five years later, produces 2/3 of Brazil’s cotton.

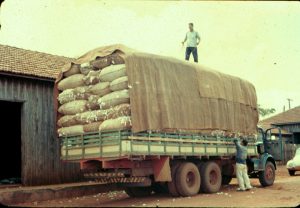

Truck loaded with harvested cotton bales read for shipping to Campo Grande. Photo by Rick Bein 1966.

Truck loaded with harvested cotton bales read for shipping to Campo Grande. Photo by Rick Bein 1966.

To visit farms we needed transportation. Peace Corps would not provide me with a vehicle but did fund the purchase of a horse. The horse was a major asset in reaching farmer further from the town.

Riding my horse with one of the local men on the main street in Pedro Gomes. Photo by Antonio Francisco dos Santos 1966.

Below are pictures I took of several types of extractive activities.

Mixture of crops including bananas, sugar cane and beans. Photo by Rick Bein 1966.

Mixture of crops including bananas, sugar cane and beans. Photo by Rick Bein 1966.

Cassava, a root crop contributed to the local diet. Photo by Rick Bein 1971.

Cassava, a root crop contributed to the local diet. Photo by Rick Bein 1971.

Bananas and maize. Photo by Rick Bein 1966.

Bananas and maize. Photo by Rick Bein 1966.

Garimpeiros sift gravel to find diamonds along stream beds. Photo by Rick Bein 1966.

Garimpeiros sift gravel to find diamonds along stream beds. Photo by Rick Bein 1966.

My house (on the right) in Pedro Gomes. Photo by Rick Bein 1966.

My house (on the right) in Pedro Gomes. Photo by Rick Bein 1966.

My “lembranca” was a going-away-gift from Pedro Serou, a descendant of the native people of Pedro Gomes. This cigarette lighter was given to him by his grandfather. Striking the flint with the piece of iron creates a spark which is caught on a piece of charred cloth contained in the tip of a cow’s horn. By blowing gently on the spark an ember glows and the end of the cigarette is placed on the ember and Inhaled. Once the cigarette is lit, the round wooden cap seals the horn, extinguishing the ember. Photo by Rick Bein 1966.

My “lembranca” was a going-away-gift from Pedro Serou, a descendant of the native people of Pedro Gomes. This cigarette lighter was given to him by his grandfather. Striking the flint with the piece of iron creates a spark which is caught on a piece of charred cloth contained in the tip of a cow’s horn. By blowing gently on the spark an ember glows and the end of the cigarette is placed on the ember and Inhaled. Once the cigarette is lit, the round wooden cap seals the horn, extinguishing the ember. Photo by Rick Bein 1966.

Peace Corps was the spark that shaped the rest of my life. From my small-town beginnings, it set me on a path of an ever expanding world of adventure. Peace Corps opened many doors and launched me into extensive career studying the environments of traditional agriculture in the tropics. My Shiva and Shakti had joined and opened me to the world. With my new-found openness to the world, I was eager for more and eager to share. “Surrender to what comes. Seek out love and pure heart”. Becoming a Professor of Geography enabled me to extend that message to my students here and abroad, I worked ten additional years with people in developing countries. I never stopped being a Peace Corps Volunteer.