43 Human Adjustments to the Environment in the Sudanese Sahel with Respect to the Current Politics of the Horn of Africa

ABSTRACT. International news media emphasis upon temporary food relief efforts in Ethiopia during 1984-1986 has overshadowed the underlying need for long-term development strategies throughout Sahelian Africa. Furthermore, a fascination with applying Western-style technology as the “solution” to Sahelian ecological problems has resulted in unexpected negative results that seldom are presented to possible aid donors in the West. Little publicized traditional approaches to environmental conditions have been successful in the Sudan, an area of Sahelian Africa on the verge of an ecological crisis similar to that of Ethiopia in the mid-1980s. Unless traditional appropriate technology is given more attention and destructive non-traditional practices reduced, the Sudan will become an even more serious version of the Ethiopia Crisis in terms of requiring massive immediate food relief and long-term development aid. By recognizing the nature of ecological interdependency, human adjustments to the environment in the Sudan can be a model to improve quality of life in the Horn of Africa and elsewhere in Sahelian Africa.

INTRODUCTION

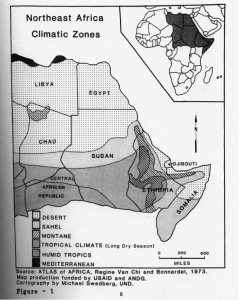

Instability, produced by political turmoil and economic delay, currently typifies the Horn of Africa (Fig. 1). Two major areas in this region can be associated with two primary sources of instability. The first, which has received many headlines in 1984-1986, is the Ethiopian core which includes highland Ethiopia, Eritrea and Somalia. This area has experienced serious chaos largely because of political turmoil related to the Addis Ababa government in the highlands. The second area is Sudan which has experienced serious instability resulting primarily from economic decay. Both areas experienced serious crop failures and famines in 1984. This compounded the already existing problems these countries already faced. The socially based problems (economic for Sudan and political for Ethiopia) have been serious for over a decade, but only have been recognized internationally when recent famines affected millions of lives.

In Ethiopia, the political situation has brought on widespread rebellion. Strong resistance movements to the Marxist regime of Mengistu have established themselves throughout the country but most notably in Eritrea. This resistance has existed since the Mengistu regime came into power in the mid-1970s. The guerrilla operations of the Eritrean rebels have presented a major obstacle to the Soviet- and Cuban-backed Ethiopian government. The rebel forces and the government have maintained a dual control of the Eritrean landscape: the rebels control at night while the government controls during the day. The degree of control has varied greatly over the last decade but with insect infestations of Eritrean agriculture during 1984, the tide has swung strongly in favor of the Ethiopian government. Being without ample food resources, the rebels have been unable to sustain their efforts. Government forces have seized this opportunity against their weakened enemy and have extended their campaign to capture much territory and to destroy what few crops then remained in the North. Many rebel families were uprooted and forced to seek both safe havens and other sources of food. Some arrived at Ethiopian government camps where they faced the uncertainties of not being fed at all and the risk of being resettled in Southern Ethiopia.

Another alternative was to flee Ethiopia and take their families to camps in neighboring Sudan. As refugees in Sudan they joined many of their compatriots who, for nearly a decade, had been using Sudan as a base for guerilla operations against the Mengistu government.

BACKGROUND TO SUDAN’ S DEVELOPMENT PROBLEMS

The Sudan’s economic stability has been seriously affected by the millions of refugees coming from several neighboring countries. Most of these are from Ethiopia. The instability of the Sudan, although influenced by many factors including politics, can be attributed mainly to its economic decline. Modern Sudanese economic history begins with the colonial period at the end of the last century. Following the overthrow of the Mahdist regime around the turn of the century, the British undertook a series of long term projects to control and to exploit the natural resources of Sudan. Gradually, a British style civil service evolved in Khartoum that formed a bureaucratic base for economic development. Dams along the Nile were constructed, over a million acres of desert were converted to irrigation, a rudimentary railroad system was established in the north, motor routes were extended throughout the country, and other infrastructural facilities were established.

Independence was granted to the Sudan in 1955 which allowed for the beginnings of indigenous inputs into what was originally a foreign imposed system. Priorities changed somewhat when national control and politics began to become an issue. Southern Sudan, somewhat content under British rule, refused to be ruled by the northern Islamic majority and undertook a rebellion which .lasted until the early 1970s: Flare-ups of this civil war have persisted into the 1980s. This internal strife was a major set back for the fledgling nation and delayed the progress of development.

Peace between Northern and Southern Sudan presented a much more stable situation for the country, which attracted large amounts of foreign economic assistance. Great Britain, the United States, Saudi Arabia, China, and several other countries invested large quantities of foreign capital into development projects in Sudan.

In spite of reports of mismanagement of funds, a number of projects reached fruition by 1985. New bridges across the Nile, a variety of agro-industries, and petroleum exploration efforts were among the projects. Most of these development efforts were oriented toward capital formation and little went to improvement of consumer comforts even though the electrical network around Khartoum, for example, was much more extensive than it had been in the mid-1970s. My general impression in 1985, after eight years of absence, was that the economy had declined in. the 1980s. Much local dissatisfaction with things in general was prominent. Disgruntlement was expressed largely about the economy and about the political reign of President Numeiry. As I was leaving the Sudan, little did I know that a successful coup-d’etat was developing.

SUDAN’ S ECONOMY IN THE EARLY 1980S

Several other factors come into play when viewing the current Sudanese economy. The fore mentioned surge of refugees from Ethiopia certainly added a drag on the economy. When crops failed in 1984 because of widespread drought, millions of rural people descended on the cities in search of food. When I viewed the situation in March of 1985, there was a notable difference in the poverty level since 1977 as many more vagrants lined the streets and there was a marked increase in the size of squatter settlements around Khartoum (Fig. 2). The facility for institutions to carry out basic activities was greatly hampered. The University of Khartoum, for example, was strapped financially, a large departure from the situation in 1977. The general economic condition of the country also could be characterized as one of general indebtedness. There are estimates in the tens of millions of dollars of what the Sudan owes to foreign countries. Inflation has taken its toll in recent years.

Figure 2: Diesel pump bringing water from Nile to irrigate that beyond the flood plain.

Figure 2: Diesel pump bringing water from Nile to irrigate that beyond the flood plain.

HUMAN ADJUSTMENTS TO ENVIRONMENTAL PROBLEMS

Yet, some of the things going on in the Sudan have kept the situation from becoming worse during the difficult times, particularly during the recent drought. First, the impact of the Ethiopian refugees in the last two years has been met largely with help from foreign countries that have been sending food and medical supplies. In some cases the donated food, rather than being delivered to the intended Ethiopian refugees, ended up in the merchants shops who sold it outright to willing consumers, thus eliminating some of food shortages encountered by drought-stricken Sudanese.

A new large irrigation project called the Rahad Scheme, instituted since 1980, is adding over a half a million acres of irrigated agricultural land. This new land has provided new opportunities for dry land farmers and nomads who would have been devastated by the recent droughts. About 20,000 families have and are being settled in the Rahad Scheme. Without this new irrigated land the impact of the recent drought would have been much more severe. I met with several of the newly settled farmers in their villages and found them to be adapting quite readily to the new lifestyle.

Many of the traditional mechanisms of meeting the hardships of the drought-prone environment are still in place. Periodic, drought is quite common in the Sahel, probably striking severely every 5 to 7 years (Griffen, 1972; El Tom, 1975). The people of the Sudanese Sahel. have over the millennium discovered a number of ways to confront the problem.

Local agricultural practices themselves have built-in mechanisms to accommodate the natural hazard of drought. A particular example is the choice of sorghum grain, the most drought-resistant of all cereals and native to Africa. Drought always has been a problem to much of Africa and native sorghum has inbred genetic diversities which accommodates drought (Bein, 1980). Upon noticing the variety of grain color in the native seed stock, the genetic diversity becomes apparent. It can also be seen that there are further genetic differences producing a variety seed sizes of grain. How many other types of diversity are in that particular grain? One does not really know, •but it must be assumed that many different strains are included in the seed stock which produce survival advantages against a variety of hazards. One seed may be resistant to drought, one may be resistant to floods, and others to birds, locusts, grasshoppers, and to whatever. The genetic diversity of the native seed stock, unknown to the farmers, provides them with a built-in, crop insurance policy. When asked about the drought of the early 1970s a group of Nuba tribesmen who planted native grain responded, “What drought?” They were subsistence agriculture oriented people and did not demand or know much of the outside world.

The people who had the serious problems with that earlier drought were those who had accepted the hybrid grains. Available hybrid grain has produced yields five times the native grain, but only during average years. Nothing could be harvested during drought years. The native grain produces every year regardless of drought while the hybrids failed. The advantages of native grain seed has been frequently ignored in the development process.

Another mechanism of drought adjustment in the Sudan is the lifestyle option of nomadic herding (Fig. 3). Nomadic herding in the Sahel is practiced through a north-south trans-humance pattern. All across the Tropical Steppe Zone, nomads move their animals north with the rainy season. When it rains they move from the Savannah Zone into the Sahel and Sahara zones to graze the grasses nurtured by the occasional convective storms.

When the grass dries out, the nomads retreat southward to take their animals to where there is water and green grass. When the rainy season returns, the biting flies in the Savannah Zone drive the nomads and their herds north again.

Traditional peasant grain storage practices are another technique by which the people of the Sudan have eased the effect of drought (Bein, 1980). Pits dug in clay soils high in montmorillonite are used to store grain (Fig. 4). A layer of chaff thrown on the top of the grain separates it from the dirt cover. Unfortunately, the technology associated with underground grain storage is being lost. There are many reasons for keeping grain in pit granaries. It can be hidden from the marauding tribes in times of war. The Koranic advice of storing grain for seven years also is met. Farmers who keep their grain in the traditional way are able to protect themselves against the ravages of drought. Fewer farmers have been able to do this in recent years as “development” is coming to Africa. With the attractions of the bright lights of the consumer society, strong forces are at work to convince these people to sell their grain in order to purchase luxuries. As a result, the effects of African drought have become more serious because people have lost their preparedness to drought. Prior to the 1970s, few Westerners heard of drought in Africa, not that the climate has changed, but that Sahelian farming practices were able to ameliorate drought conditions. The temptation to modernize has excluded past defense mechanisms.

How is the grain stored in the pit granaries? The crucial factor in site selection is soil type. This soil is made up of clay high in montmorillonite mineral. This mineral, when wet, expands and will not let water penetrate further than the top two inches. The soil acts as a sealant to water passage and keeps the grain dry. The granaries are located some distance from human habitations to reduce the problem of rodents getting into the grain. Rats and mice usually live around the human residences where there is water and other sources of food.

Figure 3: Nomads of the Sudan keep various types of animals.

Figure 3: Nomads of the Sudan keep various types of animals.

Should rodents enter the granary they will find no water and will not stay. I estimate about a 10% spoilage rate for grain kept in these “Matmouro” granaries. The alternative to the pit granary is the large elevator granary where thousands of tons of grain can be stored. Much peasant grain has been purchased by the Sudanese government and stored in elevators at Gedaref.

Figure 4: Matmouro grain storage is an effective use of environmental resources.

Figure 4: Matmouro grain storage is an effective use of environmental resources.

Large amounts of this purchased grain has been exported to raise foreign capital. The grain is virtually helping to finance industrialization in the Sudan. With the construction of the elevator granary the cracking clay soil becomes a hindrance which may eventually destroy the building. Meanwhile, the farmers who sell their grain to the government have lost their long term drought insurance. It is rumored, however, that some of the money that came from the proceeds of the grain was deposited in Swiss banks rather than being used for development.

The clay soil found in this part of the Sudan is a typical “vertisol” found in a few other areas of the world. It is also known as “Black Cotton Clay” and even “self mulching soil.” The vertisol shrinks as it dries out and leaves large cracks up to one inch wide and a foot deep. When the soil is moistened it expands and fills up the cracks (Bein, 1980). Vertisols are very problematic to manage as permanent structures are expensive to construct while tree agriculture is hampered by breaking roots.

Not only are vertisols difficult to manage, they have a very low moisture holding capacity. Soil moisture is a very serious agricultural problem when cultivating these types of soils in arid environments. Once the top two inches are wet, the soil expansion prevents any further downward seepage and the water sits on the surface until the hot sun evaporates it.

Traditional agriculturists in Sudan have learned several methods of overcoming the lack of moisture in these soils. They have found that layers of sand deposited by the trade winds will retard the evaporation of the water by holding it at the interface of the sand and clay. This particular situation will provide a source of moisture for wild shrubs and grasses or enough for sorghum cultivation if the farmer has an understanding of this environment. The use of these dune-covered vertisols has been extensive by cultivators but also by nomads who bring their animals in search of wild plant food.

In recent years, serious problems have arisen with the agricultural use of sand dunes. Because the push by government to expand agricultural production in order to finance industrialization, cultivators and nomads have grazed and cleared much greater areas of the sand dunes than ever before. Large scale denudation of the dunes has exposed them to wind, erosion and previously stabilized dunes have begun to move. It is difficult to establish vegetative growth on moving sand dunes. Ironically, even minimal agricultural use is curtailed by this over farming.

Another vertisol management technique used by the traditional farmers is flatland terracing (Bein, 1980). Six-inch high terraces are made on all sides of the field so that in the event of rain, standing water unable to seep into the soil is prevented from running off. The low terraces hold water on the ground long enough for the farmers to plant in the mud.

A cultural mechanism which exists in the Sudan accommodates another drought problem. The rainy season comes in July and August and is typified by scattered convective storms; consequently, some patches of land will not receive as much rain. The social system exists so that farm labor from the dry areas is available to help those who have received rain. Although some farmers have a crop failure they can work for those farmers who received rain and be paid with enough food for the year. Drought stricken people also provide a variety of other services for which they receive payment with food. When disrupting political forces take place, it is very difficult to maintain this inter-community and inter-tribal cooperation.

Some years when drought is extensive and there is no rain whatsoever, desperate people send the able-bodied men to seek work in distant cities from where money for food is sent home to feed the families. After a time, if drought continues and the rural granaries have emptied, the men may send for their families to join them. If families join the men, the probability increases that this becomes a permanent migration to the city. Such movement increases supplements the already significant rural-urban migration, a phenomena throughout Africa (United Nations, 1975).

Most of the drought migrants stay in squatter settlement where they are virtually camping with no utilities. Meager jobs might enable a family, should they stay, to improve their living quarters over the years, but some do return to the rural areas as’ permanent drought diminishes.

A new phenomenon has developed in the rural Sahelian Zones which was not a serious concern before thirty years ago. Development of deep groundwater resources has added a new dimension to many Sahelian communities and has drastically changed the local ecology. Fossil water brought to the surface from thousands of feet down is being used to supplement scattered shallow well water resources for nomads. This has impacted the migratory grazing cycle by allowing the nomads to keep their animals for longer periods in the Sahelian Zone following the rainy season when the grasses no longer hold water (Fig. 5). Water is now available, in many places where there was none before, and animals now can graze the standing dry grasses. Serious overgrazing has occurred with the growth of new permanent communities beside the new water facilities.

Figure 5. Camels causing environmental degradation in the Sahelian zone.

Figure 5. Camels causing environmental degradation in the Sahelian zone.

The ecological impact of the overgrazing greatly reduces the animal carry capacity of the natural pasture land for many years. When denudation occurs, wind erosion is exacerbated,, but the bare surface also increases the albido and creates a ground surface which absorbs less solar energy and which could, theoretically, produce greater drought conditions. The government’s efforts to expand livestock production by increasing water resources is counteracted by this environmental feedback.

CONCLUSION

The relationship of the Sahelian people with their environment is one of interdependence. A predominantly agrarian society is extremely susceptible to the vagaries of the environment and the impact of a natural hazard such as drought affects the entire community. Traditional technology, however primitive, has built-in mechanisms to accommodate natural hazards. Such technology should not be discarded in favor of modern methods but should be adapted with the new technology. Starting from “scratch” with modern agricultural methods is doomed to be confronted by many setbacks dealt by the environment. The trials and errors of thousands of years of traditional agriculture should have some value. Compounding political and economic disruptions with the disruption of the physical environment leaves a very unstable situation and fosters extensive human suffering.

REFERENCES

Bein, F.L. 1980. “Peasant Response to drought in the Sahel” Journal of Soil and Water Conservation, pp. 121-134.

El Tom, Mahdi Amin, 1975. The Rains of the Sudan. Khartoum, Sudan: Khartoum University Press.

Griffen, J.F. 1972. Climates of Africa. (Vol. 10). In World Survey of Climatology. New York: Elsevier.

United Nations, International Labor Office, 1975. Growth, Employment and Equity: A Comprehensive Strategy for the Sudan. New York: United Nations.