12 Our crops in Berthoud

Rick Bein

We managed a mixed crop and livestock 200-acre irrigated farm just east of the town of Berthoud, Colorado. We grew sugar beets, barley, alfalfa, corn, pinto beans, and cucumbers. Corn supported the beef fattening program and a small family milking practice.

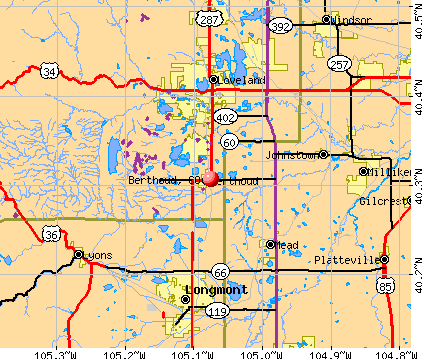

Our farm was located two miles east of Berthoud, found in the center of this map about halfway between Loveland and Longmont. The Rocky Mountain rise starts on the western edge of the map. This Map is copied from the Colorado State Highway map from 1960. 0____3 miles

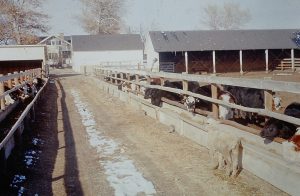

Our feedlot operation had a capacity of 1000 bovines. Steer and heifer calves, recently weaned, were purchased from cattle ranchers in Wyoming and trucked to our feed lots. The six-month-old calves missed their mothers and together would create a mooing chorus that continued for about a week.

Our cattle feed lot. Photo by Rick Bein, 1960.

Our cattle feed lot. Photo by Rick Bein, 1960.

We fed them a mixture of ground corn and corn silage, and alfalfa. This diet varied as we substituted green chopped alfalfa in place of corn silage during the Summer, and in late Fall, the cattle were allowed to graze the harvested sugar beet field for the discarded beet tops. When we switched to grazing the harvested beet field, cattle occasionally clogged their throats on extra-large beet tops. We had a few animals die from this. When chopped alfalfa replaced the corn silage in the summer, the cattle had to be watched for bloating.

The stomach would become quite distended when an animal bloated. We made the steer move and walk around to allow the gas to escape normally. In severe cases, a sharp hollow blade was stabbed into the bulging stomach to relieve the gas before the cow died of heart failure.

When a cow had a beet top caught in its throat, it could not eat or drink. We would push a thin garden hose down the throat of the cow to force the beet top down into the stomach.

A diet of fiber, like hay, grass, and chopped greens, was normal for cattle, and after three years, the cows would be ready for market. We added corn to fatten them in two years. The ground corn was a treat for the cattle, but occasionally one steer would selectively eat only the grain, and a condition called “foundering” (laminitis) occurred. It could kill the animal or leave it with locked-up, stiffened leg joints. We had to avoid this by not overloading the diet with too much grain.

We rotated our crops every year except for alfalfa. Alfalfa is a perennial that grows back every year and has a head start every spring because it does not need to be replanted. However, each succeeding year the productivity declined, and after the third year it was plowed under. Usually, we would plant sugar beets on that land the following year. Alfalfa is a hardy legume that fixes nitrogen in the soil, which benefits the next crop in the rotation.

Alfalfa grows quickly, and the three cuttings per season provided us with enough hay (baled or stacked loosely) to feed the cattle. We also chopped up alfalfa as green fodder. We made alfalfa silage out of this green “chop” to provide fodder during the winter months.

Silage was made by storing chopped-up plant material, normally green corn, but also green alfalfa, for several months while fermentation occurred. This pickling effect created an alcoholic content of about 1% which the cattle enjoyed. Initially, we used upright silos (still dotting the agricultural landscape of the USA) for the silage-producing process. Vertical elevators were used to fill the silos, and gravity was used to empty them. They did not take up much ground space, and the silage was easily tossed down to be distributed to the nearby cattle. Later, we used horizontal trench silos carved into hillsides where it would be removed by mobile loading equipment and hauled to the feedlots by trucks. It was fun, however, to climb up the vertical tower silos for a better view. But in the 60s, safety regulation was established that required the ladders to be removed when not in use.

Our farmyard is beyond a corn field. Note the upright silos for making silage. Photo by Rick Bein, 1968.

Our farmyard is beyond a corn field. Note the upright silos for making silage. Photo by Rick Bein, 1968.

Sugar beets played a mixed role on the farm. The fifteen-pound beets were dug out of the ground and immediately trucked to the Great Western Sugar factory in the town of Loveland, seven miles to the north. The beets were crushed, and the sugar juice was processed into granular sugar. The leftover wet beet pulp was loaded onto the same truck, and the farmer took home another form of cattle fodder. This pulp still had a sweet taste, and the cattle loved it. The sugar factory was unable to dispose of all the wet pulp at harvest time, so they made dried beet pulp available to feed cattle later in the year.

Mechanized Sugar beet harvester loading beets into a truck in November. Photo by Jean H. Bein, 1963

Mechanized Sugar beet harvester loading beets into a truck in November. Photo by Jean H. Bein, 1963

Sugar beets were introduced to Colorado in the early 1880s as an alternative to sugar cane by Ukrainian immigrants. Sugar cane can only be grown in the tropics and is much cheaper to produce. In order to guarantee a ready source of sugar, the US government instituted a crop subsidy for farms growing sugar beets. Sugar beets originally came from northern Europe. The beets grow well in colder climates where pests are less of a problem. Farmers applied for an allotment with the sugar factory as to how many acres of beets could be grown. We considered the sugar beets our main cash crop and were allowed to grow 30 acres.

Sugar beet growing took a lot of hand labor. At that time, the germination rate of the sugar beet seeds was not that high, and planted in clusters. And when the plants emerged, they grew too close together to allow a fifteen-pound beet to grow. Thinning with hoes had to take place. It was done by braceros who came from Mexico each summer to perform farm labor tasks. We provided a small house where they stayed. As a small boy, I used to hang out at their place, and they taught me some Spanish.

We grew barley for the Adolf Coors Brewery in Golden, Colorado, and we contracted with the brewery to grow 20 acres. The barley was stored in our granary until the Coors truck came. We always kept some Coors beer around for refreshment. Until the 60s and 70s, beer was not allowed to be marketed beyond state lines. Coors was a popular beer, and people came from surrounding states to buy it. When we traveled out of state, we would carry a case as a gift for our friends and family. When I returned from the Peace Corps, they had developed something called “Coors Light.” I could never see the reason for this because the original was already “light”! But then, the original Coors beer did not taste the same.

There were two minor crops we grew for a few years: pinto beans and cucumbers. Pinto beans were grown to remedy a shortage in Mexico and were immediately exported after harvest.

Loose pinto beans and canned pickles in jars. http://www.photos-public-domain.com/2012/04/23/pinto-beans/ Canned Dill-PIckles-1280-1524-1

We called our cucumbers pickles because that is what they became when we delivered them to the pickle factory in Loveland. It was fascinating to watch the conveyor with the slots that sorted the pickles by size. They immediately fell into a brine vat, where they remained until canning. Back home, Mom and sister Jeanie had canned enough dill pickles to provide for several years.

Hybrid corn was a major crop as it was a critical food for livestock. As I mentioned before, we fed the cattle with ground shell corn and corn silage. Hybrid corn involves crossbreeding by controlling the pollination process. Two different varieties of corn are planted side by side in a field, but the pollinating tassels are removed from one of the varieties. The variety without its tassels is pollinated by the tassels of the other variety. This process was repeated with the results of another cross-pollinated pairing. Seeds of this second crossing exceeded the productivity of the normal open-pollinated corn by 2 to 3 times. This is what we call “hybrid vigor. Unfortunately, the seed of that superproductive result was sterile, and when planted, there was no germination. At that time in the 1950s, it was the state of the art of corn farming. Since that time, science has taken this hybridization process several steps beyond to produce genetically modified corn (GMO). Each year, the seed has to be purchased from the corn breeder.

Field corn was strictly used for animal feed, and so we grew sweet corn for our household meals. Sweet corn was harvested mid-summer when the seeds were still soft and juicy. Mom and my sister Jeanie stored some and kept some in the deep freezer.

I had an intimate experience contributing to one of the hybrid corn crossings. My Dad’s friend, who was a corn seed producer, asked me, as a fourteen-year-old, to monitor the initial cross-breeding of two varieties. A one-acre plot, isolated a half mile from any foreign pollen coming from other corn fields, was set aside next to our house. My job was to detassel one of the varieties by repeatedly going through the rows of corn. I did such an excellent job that the seed producer paid me $2000.00, which was a lot of money in those days.

I participated in other projects. Our two milk cows needed to be milked by hand twice a day, and I was the logical candidate to do this chore. Learning to extract the milk from the teats was a challenge that soon became second nature. I made it fun by using the teats as squirt guns by shooting streams of milk at the cats and anyone who came to watch the milking. The cats would rise on their back feet, catching the streams in their mouths. Visitors were surprised with an eyeful of warm milk when they entered the milking parlor. The two cows produced more milk than we needed, so Dad invited the tenant farmer to do the evening milking, allowing him to keep the milk. We made many products from the raw milk, including cream, butter, buttermilk, skim milk, cheese and cottage cheese, and of course, whole milk!

I was allowed to raise my animals. As a 4H project, I entered the catch-it-calf contest at the National Stock Show. I caught a calf and brought it home, and a year later brought the full-grown steer back to the Stock Show, where it took third place for weight gain.

In my sophomore year in high school, one of the local meatpacking plants wanted to conduct an educational project for our 4-H club. They gave each of us (ten girls and boys, aged 9 to 14) a calf to fatten to the grocery store. We each kept detailed records of the amounts feed, the costs, and the monthly weight gain. At the end, we brought all of our records and grown steers to the meat packing company. They praised us for all our work and gave awards for the best bookkeeping, interesting practices, and most weight gain. We said goodbye to our steers and were told to come back the next day. We did not witness the slaughtering, but they showed us our animal carcasses hanging from a rail. The packers proudly praised our participation in this great this learning experience. As each carcass was identified to its owner, we were shown which parts were the best cuts of meat, the whole experiment fell apart. Weeping and wailing took over! Kids were traumatized, that something like this would happen to their best friend! One nine-year-old girl never got over it! The packing plant did not repeat this project.

One year, dad came across small flock of lambs to fatten. I took over the care of them and I got to keep a share of the profit. From time to time, we kept an orphaned lamb running around loose in the farmyard which my sisters took over the bottle feeding.

For my high school Future Farmers of America project, I was given a pregnant gilt for which I had to give back two female piglets of the first litter, so two other kids could do the same thing. Beginning with that sow, I had amassed one hundred pigs by the time I graduated from high school. The sale of the whole lot financed my first year in college.

My “Yorkshire” pigs. Photos by Rick Bein 1959.

Farm life served me well. In addition to all the experiential knowledge I gained, I qualified to serve as an agricultural extension agent in the Peace Corps.