56 What we did in Papua New Guinea

THREE YEARS IN PAPUA NEW GUINEA

I accepted an opportunity to take my family to live in Papua New Guinea in 1996 for 2 years. I ended up staying three years and had a wonderful, creative time. My assignment was to develop and direct the Papua New Guinea Environmental Research & Management Center (ERMC) at the Papua New Guinea University of Technology (UNITECH). I was sponsored by an Asian Development Bank grant to the Midwestern University’s Consortium of International Associations (MUCIA) through the University of Minnesota. Three amazing years of cultural immersion allowed my family to create bonds and make a real difference in the community. I worked through all levels of society to educate people on environmental awareness, and the programs I set in motion are still making an impact.

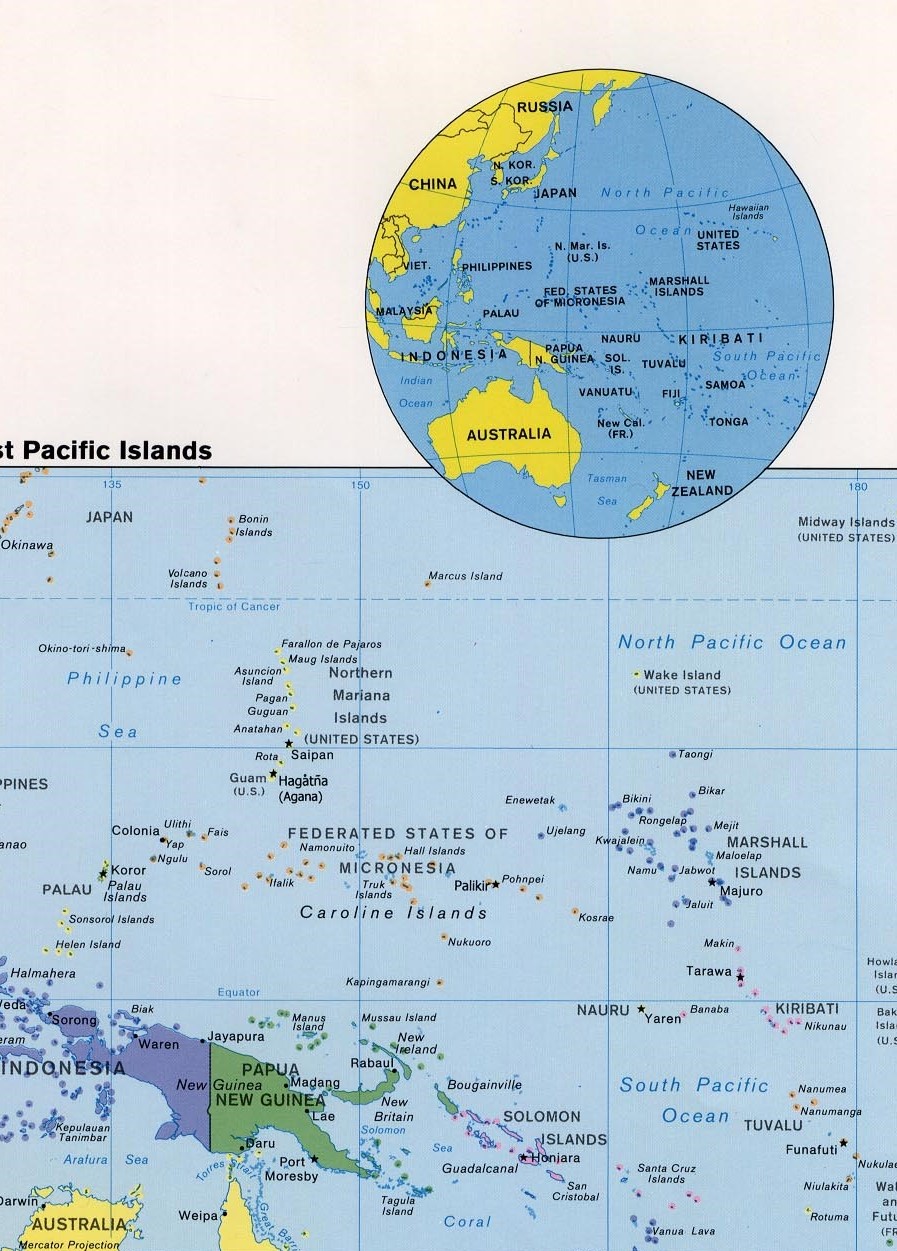

Map produced by the Central Intelligence Agency, 1998, Public domain Perry-Castañeda Map Library, University of Texas

It became obvious to me shortly after my arrival that this mission could best be served by promoting “environmental awareness.” I found that environmental awareness could be developed at many levels, and I undertook it first at the University level, and then I focused on local and national government, not-for-profit organizations, the primary and secondary schools, and finally in the village.

My campus activity at Unitech began with the “Environmental Lecture Series” by inviting environmentally related people who were visiting PNG to speak to a public audience. These talks were advertised on campus, and my mailing list grew to include all provinces in the country. In the three years, the ERMC sponsored 22 speakers who drew an average audience of 40 people, mostly students, faculty, and townspeople.

Each semester, I taught environmental studies to 100 university freshmen and introductory Human and Physical Geography to the Surveying Department Sophomores. I also taught courses on environmental impact assessment.

The ERMC sponsored a publication, Environment Papua New Guinea: Collected Paper Series volume 1, which was printed in July 1999. This academically peer-reviewed volume included 13 applied environmental articles from ten different academic disciplines. At the center, we arranged to have the papers peer-reviewed by academics in other university departments both in PNG and overseas. This work is available and is used in PNG by university students, government agencies, and not-for-profit environmental groups.

The plans for the development of an ERMC building to house the Environmental Center were underway. With European Union funding, groundbreaking began in January 2000, the “drier” season. I also developed a postgraduate program in Environmental Management.

The work off campus was the most exciting because there were few limiting institutional parameters. Two highly creative opportunities presented themselves with offers to the Center: 1) coordinate and direct a biodiversity inventory in a coastal village wildlife management area, and 2) facilitate an environmental education program for the primary schools of Morobe Province.

The biodiversity inventory got me into the “bush,” which was only accessible by boat about 30 miles down the coast. Over the three years, I made about fifteen visits to Lababia Village, where I developed a path that reached from the open sea to the top of their mountain for sampling nine biomes (identifiable vegetative communities like rainforests and coral reefs). I arranged for thirteen different biologists with targeted specialties to inventory the different parts of the environment. So far, fifteen previously undiscovered species have been identified from this study. The study also outlined a series of recommendations by which the villagers, with the guidance of a not-for-profit organization, could sustain their livelihood and the environment as well.

Three village hunters, Levi, Inok, and Tani, are taking a break from building a transect through the rainforest. Photo by Rick Bein, 1998.

I enjoyed this more than any other part of my Papua New Guinea experience. The three village hunters were the strongest and most knowledgeable of the Lababia territory. Together we explored out to as far as they had ever gone, then we cut a slit of a research trail into their untouched pristine rain forests. When we encountered the spirits of their ancestors, they urgently wanted to go back. It took some convincing that the spirits were “showing us the way” to get them to continue the journey. We continued up the mountains and explored the environments of their higher elevations, where the persistent heat yielded to cooler, more temperate climates.

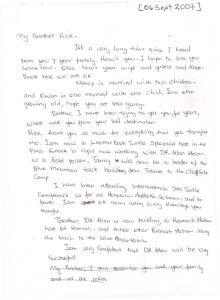

One of the village hunters, Levi, to whom I became a mentor, sent me the handwritten letter of appreciation seven years after I was last there.

Letter from Levi Ambio, 2007.

The environments, or “biomes”, began with the coral reefs, which provided a large part of the diet, but with the coastal flood zone, provided a different variety of wildlife and plants. Several other biomes emerged as the mountain hinterland took over. A very bio-diverse rainforest, hardly explored, occupied the land up to about 3000 feet elevation. Gradually, as the elevation increased, the landscape cooled, and different biomes began to appear. The tall, canopied rainforest was gradually taken over by lower-laying, but dense vegetation. By 4000 feet, the vegetation was quite dense and almost impenetrable. Above this, the vegetation blended into a low-growing fern forest.

With all the backpacking and hiking that was required, I became more fit than I had been since high school. This prepared me for climbing the 14,500-foot Mt. Wilhelm, the tallest mountain in PNG, and for enduring the six days of the WW2 vintage Kokoda Trail.

My experience with the Geography Educators Network in Indiana, the National Geographic Society, and the Indiana Geography Institutes paid off with the environmental education effort in Morobe Province. The Wildlife Conservation Society’s Bronx Zoo of New York offered to bring their education team and a truckload of teaching material if a workshop for primary teachers could be organized. I worked closely with the Rainforest Habitat (located on campus), which was able to arrange for a grant to bring in 100 teachers to attend the workshops on campus. I coordinated these two groups with the local provincial school administration to select the teachers.

Primary grade schoolteachers in a workshop sponsored by the Wildlife Conservation Society. Photo by Rick Bein, 1998.

Remains of a Japanese plane propeller stranded on a reef adjacent to an outrigger canoe. Photos by Rick Bein, 1998.

In my estimation, these workshops probably had more impact on environmental awareness in PNG than any of the other projects in which I was involved. This brought environmental thinking to the village level in the rainforest, where conservation efforts need to be introduced and monitored. The one hundred teachers went back to their schools, where each teacher teaches between 30 and 40 children each year. I began getting reports from other university field workers who were challenged by students in the villages about the environment.

The style of teaching presented by the Bronx Zoo was mostly hands-on, something quite different from the still-used British-style lecture from decades ago. This was immediately embraced by the teachers who returned to their schools with new enthusiasm and inspiration for their students. The “new” teaching methodology, in turn, captured the imagination of the parents who experienced the excitement of their children about something that they themselves understood and in which they could also participate. This greatly empowered the teachers who became the leaders they should have been in their villages. A second group of 100 teachers went through in April 1999. As in the first year, the teachers are flooding the Environmental Research Management Center (ERMC) with letters sharing their success and continued enthusiasm.

The Asian Development grant that supported us allowed all of our children younger than twenty-one to join us in this adventure. Only our youngest two lived with us, but it provided a return airline trip for four of our other children to come to Papua New Guinea for an indeterminable time. One of them, Candy, came and enrolled for a semester at the University. Her PNG college credits were accepted at Indiana University.

Our two children, Molly and Kristen, became immersed in the culture and attended the Lae International School, whose student body contains students from about 30 nationalities. Half of the students were Papua New Guinean. Molly graduated from high school there and made some long-lasting friends with whom, thanks to e-mail and social media Facebook, she is in regular contact. Molly also joined the local softball team and became the only foreigner in the whole country to participate in league play. The local Rotary Club honored her with the all-city high school student award for “Community Spirit and Volunteer Time.”

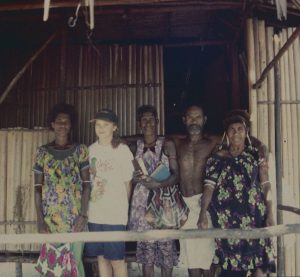

Molly, playing 3rd base, was the only non native to participate in the PNG National Softball league. She also perfected her deep-sea diving skills. Kristen stayed with the Kamiali Village elders when I was preparing a biological trail. The elderly ladies took her under their wings and took her to their gardens to harvest and carry back vegetables and to experience their bathrooms in the sea. Photos by Rick Bein, 1999.

Our youngest daughter, Kristen, though not as gregarious, made many continuing friends and has good memories of PNG. When I was working with the village hunters to build the biological trail, I left her for three days with the villagers. The old woman in the picture below took care of her as if she were one of their own. She went out to the food gardens and carried back vegetables to the village, bathed in the ocean, and participated in other activities. Kristen excelled in schoolwork and played the lead in one of the school plays. When she finished 8th grade in PNG, her writing skills far surpassed those of mine when I finished high school!

Maryellen, my spouse, became ultra-involved in all aspects of the community and volunteered for many women’s groups. She served on many committees and clubs and, for two years, was president of the PNG chapter of Soroptimist International, a women’s organization that began in California in the late 1920s. She also actively served as president of Sisters United, which provided a support group for women moving out of traditional feminine roles and into professional work. These included counseling at the women’s prison, preparing them for their eventual release.

She helped one woman who fled her highland village because she had killed her husband in self-defense, and the tribe was going to kill her in retribution. In Lei, she was homeless on the streets and found the nuns at a Catholic charity group. Maryellen, who was volunteering with them, arranged a place for the woman to stay with the nuns and brought her a pair of rabbits to start breeding them to provide a steady source of food. Thirty months later, having forgotten all about this, Maryellen was surprised in the market when this highland woman ran up and hugged her. “You gave me those two rabbits, and now I have 50 of them and have a business selling rabbit meat and skins. I want to thank you.” This was such a touching story that it is recorded here in her memory.

Maryellen became active with the Life Education Center, Women’s Business training program, Morobe Tourism Promotion Association, University Female Student Association, and was a guest speaker for numerous women’s organizations throughout the City of Lae. Maryellen created an extensive flower garden surrounded by a hibiscus hedge around our house. Photos by Rick Bein, 1997.

Maryellen received special recognition by the Women of Lae, by all women’s organizations, and The Ladies of Lae for all her “volunteer work and awareness created by crossing the lines between expatriate and national women, creating bonds for future projects and endeavors.”

We did endure some hardships, like food poisoning after eating at the University Staff Club. That was diagnosed at the campus clinic a week later. The medic asked why we waited so long to come. Maryellen caught tetanus from the barbed wire that she brushed against while waving to get someone’s attention. That was also treated at the clinic. Malaria attacked each of us at least once. I contacted it at least three times. Quinine was readily available, and we experienced no long-term effects.

The ever-present betel nut chewing was a distraction. Betel nut trees were common, and the soft nuts were chewed along with daka, a local herb, plus lime from ground-up seashells. This was the local addictive sedative that produced a fifteen-minute high plus lots of blood-red saliva that the people spat freely out on the streets. I tried it and experienced a slight feeling of relaxation, but found that I was not an exact spitter, and I ruined a couple of shirts.

One time, as we walked down to the end of Markham Place, the street where we lived, we were accosted by some rascals who brandished machetes while they were robbing one of the apartments. They had entered the neighborhood by wading down the drainage ditch behind all the homes and found a hole in the fence. They told us to go back and did nothing to us as we presented no threat to them. Of course, we did report it to the campus authorities.

The return to the States in some ways was difficult. The many comforts of life were greatly appreciated, but it is that extra awareness that placed us at some distance, knowing that the experience cannot be passed on, nor appreciated by those with whom we come in contact. “How was Papua or wherever you were?” A simple answer is all that is wanted. After anything other than “fine,” the eyes glazed over, and the urge to share this wonderful experience was stifled.

Being a big frog in a small pond has its merits. Having achieved a high level of esteem in PNG, we were now just “part of the crowd.” Being lost in the crowd is humbling.

It was like Rip van Winkle returning. After only three years, the readjustment to the US was challenging. Changes involved new laws, vocabulary, and rules, increased technology, and the availability of anything possible that you can buy. In our absence, America had begun an internet and cell phone revolution, which incrementally may not have been noticeable, but it sure was a leap after three years. Driving on the right side of the road and from the left side of a car that does not have a clutch presented a small challenge. I got a traffic ticket in the first week! What is my niche? I am not what I was when I left. How do I fit this all together? My reorientation to life in the States was slow, but that enables me to continue relating what I learned. I continued to relate my PNG experiences in bite-sized doses to my family, students, and friends.