63 Adventures with Turtles

Rick Bein

Sea Turtles nest on most tropical beaches around the world. Many countries are now engaged in preserving these endangered species. This effort is long term since many of the turtles do not sexually mature for decades. The Leatherback, for example, only begins nesting when it becomes 30 years of age.

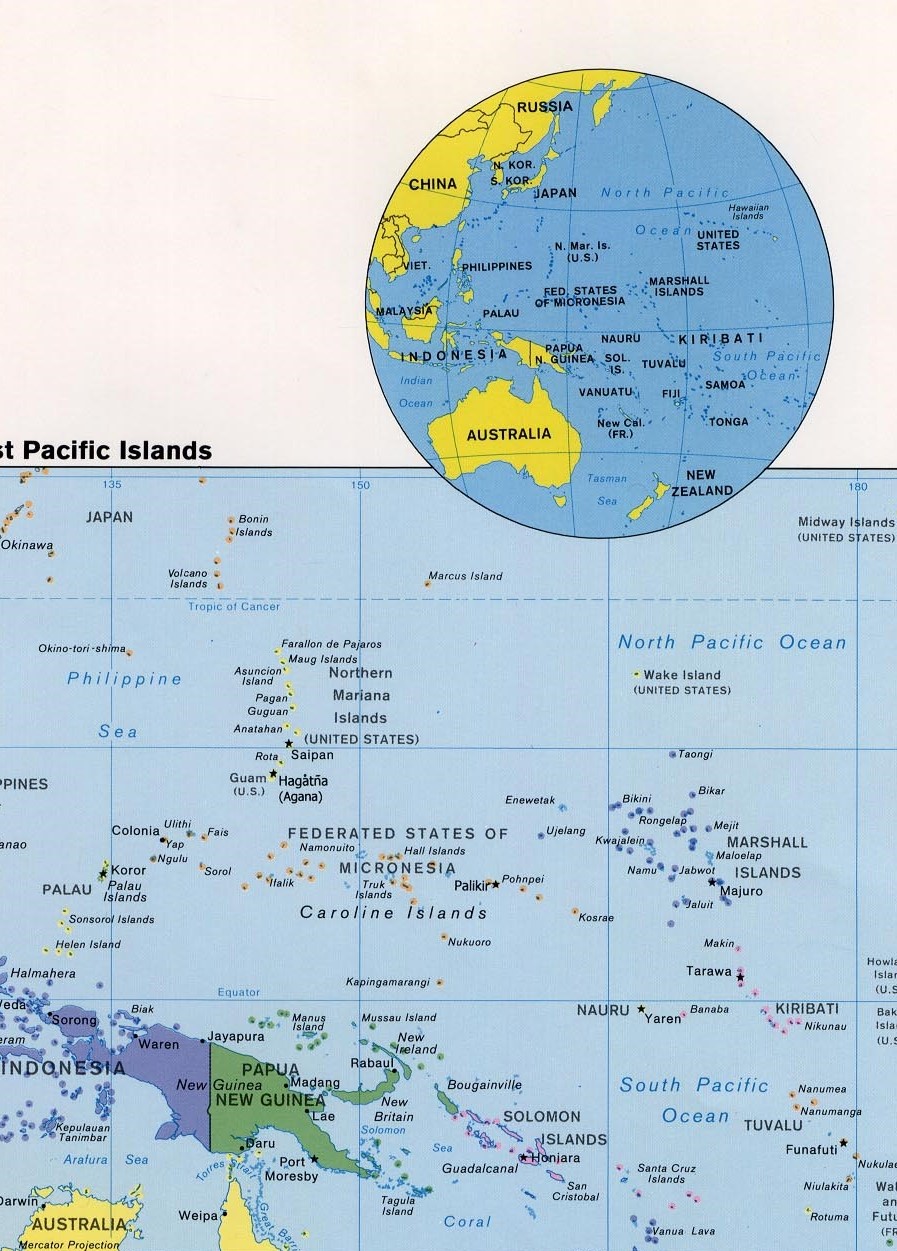

My first experience with sea turtles happened when I was working in a coastal village in Papua New Guinea (PNG). I had always heard of sea turtles as an endangered species, but never from a firsthand perspective. I had been working on contract with the NGO Village Development Trust (VDT) whose purpose was to conserve environments in Papua New Guinea. They had established an introductory relationship with the village of Lababia located forty miles south of the town of Lei along the east coast on the Solomon Sea. Their approach was two-fold: 1) create a scientific research station and 2) develop an eco-tourist program.

Papua New Guinea, by the Australian Geology survey. 2007.

Papua New Guinea, by the Australian Geology survey. 2007.

As a visiting professor at Papua New Guinea University of Technology (UNITEC) in Lei, I was on an Asian Development exchange Grant to develop an Environmental Research Management Center on campus. My mission was to develop an environment focus among the academic departments through their teaching and research programs. VDT contracted me to build a research transect from the Lababia Village extending up the 6000-foot Blue Mountain behind. Being a pristine rainforest, the transect would provide a path for biologists to sample the unique fauna and flora.

Over the next two years my efforts extended beyond the mountain transect and I became involved with the Kamiali people, the residents of Lababia Village. The Kamiali thrive along their 15-mile-long coast engaging in fishing and gardening. The villagers invited me to experience much of their way of life. At one point, I discovered that their extended beach was a nesting habitat for Leather back turtles.

My visiting stepdaughter, Candy Riggins and friend observing a nesting turtle on the Kamiali’s beach. Photo by Rick Bein 1997.

My visiting stepdaughter, Candy Riggins and friend observing a nesting turtle on the Kamiali’s beach. Photo by Rick Bein 1997.

I spent some time observing the female turtles coming on the beach and creating nests, laying their eggs, and returning to the ocean. I also became aware that none of the eggs ever hatched because the villagers dug them up and consumed all of them. I asked if any hatchling turtles were ever seen. The answer was “no.”

Villager standing beside a nest, showing turtle eggs impaled on a stick. Photo by Rick Bein 1997

Villager standing beside a nest, showing turtle eggs impaled on a stick. Photo by Rick Bein 1997

I decided to consult Levi Ambio, with whom I worked closely building the transect. Levi explained that the Kamiali considered the turtle eggs their gift from the universe and that it was their right to eat them. I asked him how the turtles would continue to nest if there were no new turtles to replace the old ones.

That notion struck home, and we began talking about how the villagers could give up this annual treat. He thought that would be difficult, but he said he would establish a no-harvest zone along a 100 meter stretch of beach right next to the village where he could keep watch. I was doubtful that this would work but worth a try.

I had to return to the States shortly after that and forgot about his endeavor. I went back to my teaching and research. I was awarded a travel grant to return to PNG the next summer of 2000, to follow up on my research on the food gardens of Kamiali.

When I arrived at the village, Levi greeted me with the news that for the first time in his life he witnessed hatching turtles marching down to the ocean. I was thrilled that I had made an impact.

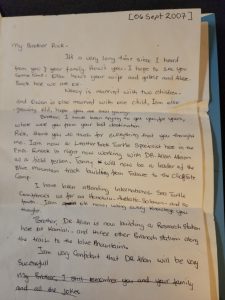

After that, I had little contact with PNG, and continued with my work at IUPUI. A surprise handwritten letter from Levi arrived in 2007. In it, he explained what was happening to him. See copy of the letter.

Letter from Levi Ambio 2007

Letter from Levi Ambio 2007

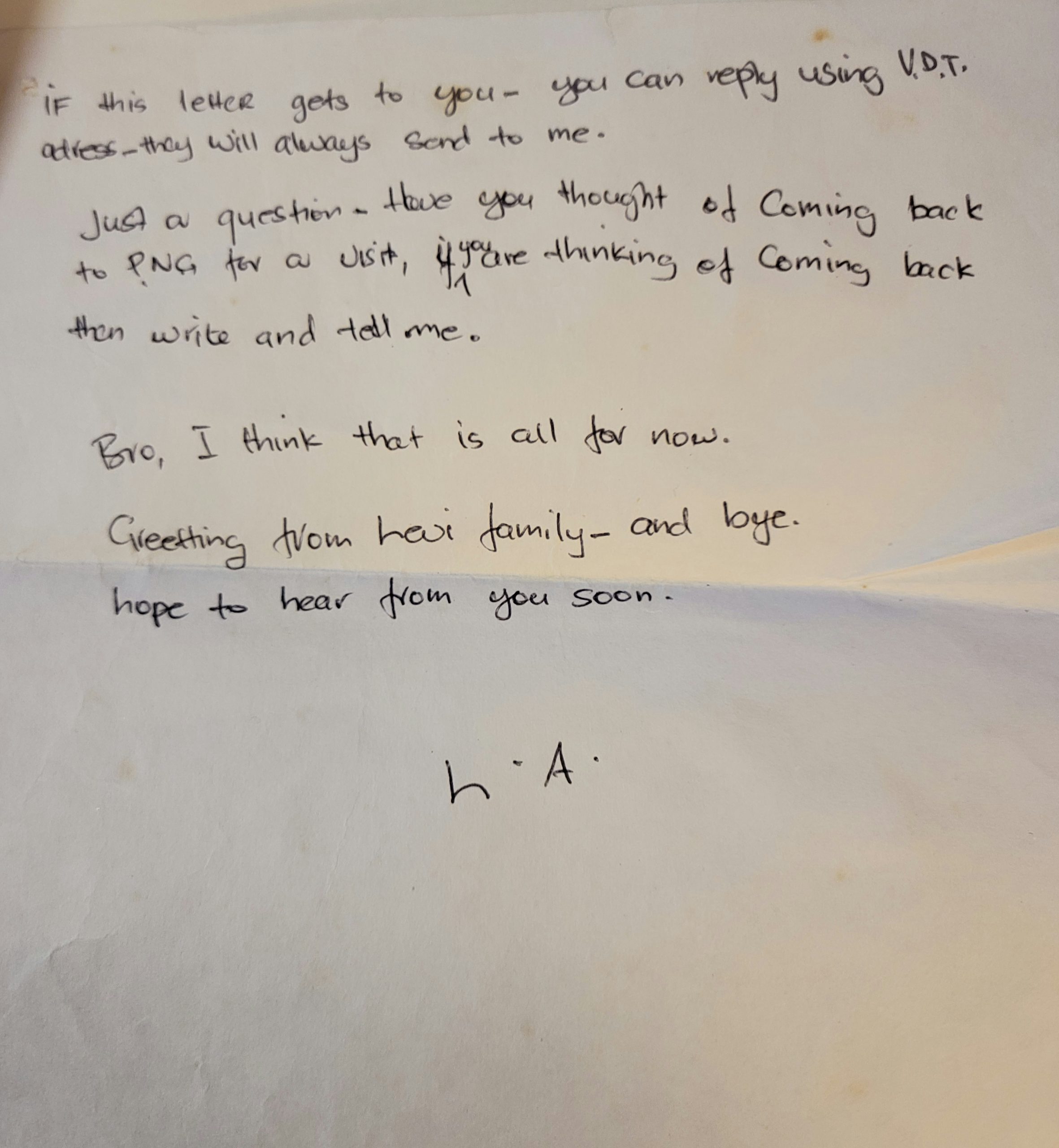

My second experience with sea turtles was a major hands-on adventure. The ANAI Marine Turtle Conservation Project presented an opportunity to work with sea turtles in Costa Rica in 2001. They advertised for a university professor to lead a group of student volunteers to work in a turtle conservation habitat on Gandoka Beach, Costa Rica. Gandoka was located on the Caribbean side of Costa Rica, bordering Panama. I recruited a team of seven students who enthusiastic enrolled in the adventure.

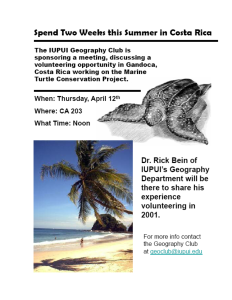

CIA map of Costa Rica. The ANAI Marine Turtle Conservation Project located southeast of Puerto Limon on the Caribbean coast on the most southerly point next to Panama.

Costa Rica has taken the lead in protecting our terrestrial environment. Even though they are a small country they have invested a major effort in developing their country with a focus on the environmental conservation. Arriving at the airport, one faces about six recycling receptacles starting with paper, cardboard, plastic, glass, and metals. Locals are accustomed to recycling and are ready to remind others when they fail to do so.

Former Cost Rico president, Oscar Arias was the brainchild of this effort. In every way possible they have adopted conservation practices, beginning with recycling and habitat preservation. This effort has fostered an economy around Eco-tourism which brings people from all over the world to experience rainforests, savannas, wetlands, mountain forests, tundra, and even beach habitats. Nesting habitats extend to the rest of the world and many species migrate annually starting in Costa Rica.

Sea Turtles are an example as they come momentarily to lay their eggs and then spend the rest of the year at sea. They are trying to stop this age-old practice or eating the eggs by establishing sea turtle egg nurseries on several beaches. The habitats are high maintenance operations and require significant labor. Costa Rica has invited environmental enthusiasts from around the world to volunteer at these habitats.

Flier promoting the work-study course

Flier promoting the work-study course

We arrived in early July 2001, and they gave us a week to tour some of the traditional Costa Rica tourist sites like Monte Verde and Arenal Volcano. Then we went to work at the ANAI turtle nursery at Gandoka. Initially that involved learning how to patrol the beach, keeping away from turtles coming on to the beach, identifying where eggs have already been laid. We patrolled in pairs and took shifts during the night recording where turtles nested and we had to keep an eye out for poachers.

A controversial counter movement claiming “the harvest of some eggs for food is in keeping with preserving sea turtle eggs” has emerged in the province of Guanacaste Costa Rica at the Ostional National Wildlife Refuge. Photos by Desarrollo de Areas Conservacion.

A controversial counter movement claiming “the harvest of some eggs for food is in keeping with preserving sea turtle eggs” has emerged in the province of Guanacaste Costa Rica at the Ostional National Wildlife Refuge. Photos by Desarrollo de Areas Conservacion.

The turtle egg laying season in Costa Rica is during the months of May, June, and July. It is said that a leatherback turtle can lay up to sixty eggs three times in a season. Few of the eggs hatch, not to mention all of the hazards a turtle goes through to reach adulthood at 30 years of age.

The leather back approaches the beach cautiously, looking out for predators, and seeing none it continues through the breaking waves on to the head of the beach, and on to the furthest extent of the sand. She chooses a site, and stirs up a 15-foot perimeter in which she digs a hole as deep as her flipper can reach. At that stage she ignores any disturbance that might distract her.

Leatherback leaving the water, Open nest exposed by poacher. Photos by Rick Bein 2001.

This nest was buried this deep, but a storm eroded the sand exposing the nest. Team member has to dig quite deep to reach the eggs. It is easier to place a plastic shopping bag in the hole to catch the eggs as the mother lays them. Photos by Rick Bein 2001.

The eggs collected are moved to holes dug in the protected hatchery. Sandbags protect against high tides and storm surges. The enclosure prevents predators from reaching the eggs and plastic cages cover nests to contain baby turtles before releasing them to the sea.

A full hatchery midway through the season. Baby turtles coming out of the sand to be gathered and taken all together to be released. Photos by Rick Bein 2001.

Blue containers containing hawk-bill hatchlings being taken a few hundred meters up the beach from the hatchery to avoid sea predators waiting for early escapees from the hatchery. Hatchlings are released at the top of the beach to allow the march to the sea to strengthen their flippers for swimming. If released directly into the sea, they will drown. Pictures by Rick Bein 2001.

Hawk-bill hatchlings marching to the sea. Leatherback hatchling leaves a trail in the sand. Photos by Rick Bein 2001.

We assisted with the closure of the hatchery at the end of the season July 30, 2001. All unhatched nests had to be opened and eggs inspected. Records of the condition of the eggs were recorded. Photos by Molly Funk 2001.

Indiana turtle conservation team, Costa Rica 2001

Indiana turtle conservation team, Costa Rica 2001