76 San Miguel Canoa: Language change after 34 years.

In June 1985 colleague, Professor Barbara Jackson and I took university students on a summer field trip to explore central Mexico. This took us to Puebla where we explored the city and the State. One particular site that caught our eye was a small settlement named San Miguel Canoa (population 3000, elevation 9500 feet above sea level) halfway up the dormant cone volcano called La Malinche. Photo by Rick Bein 1985

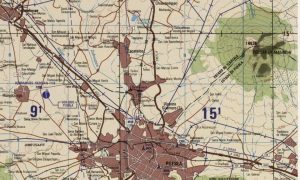

Malinche Volcano northeast corner includes the town of San Miguel Canoa (canola) cropped from the Topographic map of Puebla from the public domain in the Perry Casteneda University of Texas. The village is shown at the dead-end road halfway between City of Puebla and the Malinche.

We wanted our students to see something off the beaten touristic path and decided that San Miguel Canoa would fit that purpose. Our bus driver was a little leery about going up there because of the little community’s reputation for being rebellious toward the Mexican Government.

I learned later that in 1968 the town wanted to keep their indigenous traditions and had executed five employees of the University of Puebla who had decided to climb La Malinche. The government sent the military and gunned down 400 people, mostly the demonstrating youth! This event had left a negative impact on the community which eventually obtained a semi-autonomous status with the Mexican Government.

The driver decide that it was ok to go there, but the road was quite difficult, rutted and steep. At one point it was too steep for the bus to proceed, and we all disembarked, preparing to walk the remaining two miles, but then, without the weight of our group, the bus was able to pass over the steep section and we all got back on again.

San Miguel Canoa street scenes 1985 (left), 2019 (right). La Malinche volcano in background in left photo. Photos by Rick Bein.

Left, corn shocks, in back ground near building 1985. Right, similar corn shocks in 2019. Photos by Rick Bein

At the main plaza we began exploring the town. The people seemed friendly and polite but would not talk to us. Our students kept trying to practice their Spanish to no avail. After thirty minutes a local man in his early thirties began talking to us in perfect English. As it turned out he was a veterinarian trained at an American University and had come home to practice.

One of our students asked, “Why won’t they speak to us in Spanish?” He responded, “They don’t speak Spanish here.” “Well, what do they speak?” The veterinarian said, “They speak Nahuatl, our mother tongue. People refuse to speak Spanish here.” This made sense after I learned some of the history.

We spent a couple more hours, looking around, taking pictures, and talking to the veterinarian.

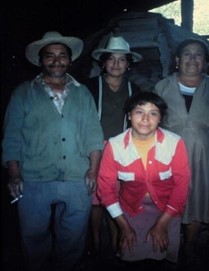

Family in San Miguel Canoa and their sweat lodge. Photos by Rick Bein 1985.

The return

In 2019, I had the opportunity to visit San Miguel Canoa again. Attending a conference in Atlixco, another town in the State of Puebla, I spent an extra two days to see if things had changed in this little mountain after 34 years. A group of colleagues from the conference decided they would join me for this little jaunt. We hired a taxi to take us to the same plaza as before. The road was now asphalt as opposed to dirt, but the farming landscape appeared much the same with corn shocks sitting ready to be threshed. The changes were amazing! The population had increased to 14,900, there were many new buildings, and the market was abuzz with people bustling with street vendors everywhere.

San Miguel Canoa market vendor selling ice cream and small grocery store. Photos by Rick Bein 2019

Ever-present stray dogs in San Miguel Canoa. Photo by Rick Bein 2019

People were quite friendly and helpful. They were proud of their town and showed off the cathedral and a small museum. Interestingly, many of the people did not like their pictures taken. I had to ask each time and many times the answer was no.

Spanish seemed to be spoken everywhere. I wanted to know “What happened to the Nahuatl?”

As I was sitting in a street side café, I began asking questions. A curious nine-year-old boy asked me where I was from and wanted to hear a few words in English. I accommodated him and asked if he spoke Nahuatl. “He responded, “Poco”. Then I asked one middle aged vendor if he spoke Nahuatl. His response was, “Mitad y Mitad, Espanola y Nahuatl. (Half and half) He said his elderly parents only speak Nahutatl.

To see for myself, I asked an elderly man what languages he spoke. He didn’t understand my Spanish and grinned and waved at me and pointed to a younger person.

I became clear to me that the overwhelming dominance of the growing economy created the necessity to speak Spanish and soon Nahuatl would eventually disappear. We are seeing the slow death of an indigenous culture.

References:

Chrisman, Kevin M. (19 April 2013). “Community, Power, and Memory in Díaz Ordaz’s Mexico: The 1968 Lynching in San Miguel Canoa, Puebla”.

Cline, Sarah (2000). “Native Peoples of Colonial Central Mexico”. In Richard E.W. Adams; Murdo J. MacLeod (eds.). The Cambridge History of the Native Peoples of the Americas: Volume II, Mesoamerica, Part 2. New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 187–222.