35 Land Use patterns along the Nile

LAND USE PATTERNS ALONG THE NILE

Spatial relationships among phenomena on the earth’s surface are a concern of the geographer. Explanations of these relationships are sought by examining all aspects of spatial phenomena, and when it becomes apparent through repetitive observation that certain processes have causal effects on spatial relationships theories are formulated for universal application. The basis of geographic inquiry is location. The use of location theory other than to explain landscape patterns enables planners to determine the effects brought about by the changes they would introduce. The knowledge of the forces influencing existing landscape patterns also provides planners with a basis for adapting their schemes to the landscape.

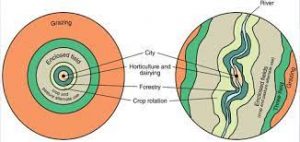

One of the most noted of location theories is the Von Thünen land use model, or “concentric rings” theory (Figure 1). In 1803 Johann Heinrich von Thünen devised a model predicting land uses around the market centre. In this model he hypothesized that land use will change as a function of distance from the centre. This is explained in terms of transportation costs. Priority of land use will go to the activity yielding the highest net return per unit area of land. The net return or economic rent is then determined by variable operating costs, the most significant being transportation to and from the market. A product difficult to transport can only be economically feasible when grown near the market and when demand is high enough to justify it. Each location with respect to the market has a set of cost variables which in turn determine the land use bringing. the highest economic rent.

Products of demand which are bulky, perishable and otherwise difficult to transport are cultivated near the market so as to reduce transportation costs. Those products which are more easily shipped are produced further from the market unless the demand for them is exceptionally high. The resulting land use pattern is a function of transportation costs, and with distance from the market the products of the land use will bear decreasing costs of transport per unit.

Several assumptions are made to clarify the model. First, there must exist an economically isolated and homogeneous agricultural region which consists of one market town. All production is sold and all consumer items are supplied in this town. It must also be assumed that all of the people of the community have freedom of choice and behave in order to maximize profits. Transportation methods and soil fertility are assumed to be the same throughout the region. Von Thünen conceived of this idea in the context of early nineteenth century Germany when transportation was by horse cart and the most difficult products to be shipped to the market were vegetables, fruit, dairy products and firewood. The production of these constituted the land uses nearest the market. Further away, the land use decreased in intensity of cultivation as fallow periods and land livestock grazing increased. In the last case livestock. though low in production per unit area, are the easiest to take to market.

|VON THÜNEN LAND USE PATTERNS December 16, 2020 | Agricultural Geography

APPLICATION TO KHARTOUM

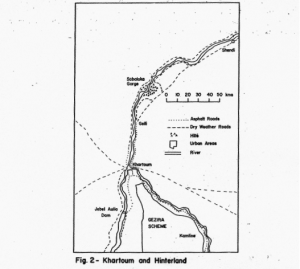

Applying this model in the context of 1976 and to the markets of the Three Towns, some of the crop patterns would be changed. In addition, the assumption of the homogeneous plain would need to be relaxed to include the Nile River. The lower half of von Thünen’s idealized land use pattern of Figure 1 includes the passage of a river. In the case of the Nile, however, the presence of the river does not produce a transportation advantage but does improve soil fertility and irrigation potential. The Von Thünen land use model as applied to Khartoum must be modified to include the different types of land and the different resources available (Figure 2). This particularly reflects the nature of the climate and the nature of the Nile. The climate is arid and intensive agriculture must depend on irrigation. The irrigable areas must be treated separately in terms of land use type from the non-irrigable areas.

The annual flooding by the Blue Nile creates an area along the River bank called the gerif (Figure 3) which is inundated and covered with a layer of silt each year. Although this land is limited in area it is cultivated as the water recedes. Except where the gerif is relatively level and where irrigation and ox ploughs can be employed most of this land is cultivated with the ancient use of the dibble. Investment in improving the steep gerif is not practical as the next season’s flood may wash it away or cover it. Most of the gerif is cultivated with vegetables and subsistence crops while distance from the market does little to change the pattern. Only the flood plain with its rich soil 50 to 100 metres wide on either side of the river is irrigated by traditional methods. Diesel powered pumps have recently made it possible to extend the irrigated area beyond the flood plane or where the flood plain is wider. Nevertheless, the irrigated area forms a linear pattern following the Nile. Except for the, Gezira, where half a million hectares has been brought under irrigation, and the specialized pump schemes, nearly most of the irrigated land in the Sudan is within a “stone’s throw” of the Nile.

Nile River from a steamboat looking across flood plain reaching to the date trees on the edge of the desert. A diesel fuel pump irrigates a variety of crops in the flood plain.

Nile River from a steamboat looking across flood plain reaching to the date trees on the edge of the desert. A diesel fuel pump irrigates a variety of crops in the flood plain.

Non-irrigated land is in abundance in the Sudan and its agricultural use depends on the chance of a passing thunderstorm during the brief rainy season in August. Two types of agriculture are practiced on this land: grazing and rain cultivation. Grazing is most dominantly practiced by the nomads but also by a few semi-sedentary farmers. Herds of sheep, cattle or camels are taken to the areas where the rainfall has brought the desert vegetation to life.

Rain cultivation in the arid zone is a marginal activity whereby farmers with good soil are willing to gamble on one or two rains to bring up their sorghum crop. This is practiced where catchments of water runoff from other areas is possible.

A land use pattern for the Khartoum hinterland can be defined along the principles of the Von Thünen model. That is, the land use of highest economic rent will reflect the relative transportation cost to Khartoum. Bulky or perishable crops will be cultivated nearer to Khartoum while crops easy to transport will be located further away. One would expect vegetables, fruits, and milk to be produced near Khartoum and seed crops like grain, beans and ground nuts to be grown in more distant places. The actual pattern observed. must be analyzed in terms of two basic land use types: irrigated and non-irrigated. Irrigated land use is restricted to the area of the Nile flood plain and is examined in terms of crops cultivated and relative ease of transportation to Khartoum.

LAND USE ZONES

I. Green vegetable zone located in and around Khartoum extends along the irrigated Nile flood plain up to one hour away by lorry. In this zone all the perishable greens and vegetables consumed in Khartoum are produced. Also included is the production of alfalfa to feed several thousand dairy animals. The principal areas are Shambat and Kaduru north of Khartoum; Hillat Kuku, Haj Yusif, Gereif and Filafoun east of the Blue Nile; and south of Khartoum along both the White and Blue Niles. The existence of asphalt landscape roads has extended and solidified this zone.

Irrigated salad greens on Tuti Island at the junction of the Niles.

Irrigated salad greens on Tuti Island at the junction of the Niles.

Where the farmer has no decision in the crops grown such as in the specialized irrigated schemes under government control, the land use is not considered for analysis. Non-irrigated land is in the area beyond the physical influence of the Nile. The use of this land is heavily influenced by climate but the effect of market proximity is evident. Zones of agricultural land use in both cases are distinguished by the dominant cash crops and the intensity of activity. The immediate hinterland providing the majority of the food requirements for Khartoum extends to Northern Province and the Gezira Scheme (Figure 4). Several zones are evident on the landscape.

2. Intensive dairy grazing zone within the same distance from Khartoum as zone I is located on the non-irrigated lands. The grazing of goats is the most common activity in this area.

3. Banana zone is located beyond the main belt of horticultural activity. The main specialized zone is 60 kilometers north of Khartoum centered at Wad Ramley. The majority of bananas coming to Khartoum are not produced here, but come form Kassala where better climatic and soil conditions exist.

4. Pastoral and rain cultivated zone constitutes the land use throughout the remainder of the non-irrigated area and extends for great distances into the desert. The availability of drinking water from wells and hafirs determines whether these activities exist at all. The area used is generally within walking distance from the Nile.

Animals such as camels, sheep, goats and cattle are located away from the Nile and graze lands where occasional rains occur. Rain cultivation includes Millet along with sorghum which are drought tolerant cereals grown in the Sahelian zone where there is marginal rainfall. Photos by Ric Bein 1974.

5. Onion zone is a specialized horticultural area of Wad El-Basal occupying the flood plain between Wad Ramley and the Sabaloka Gorge. The bulky onions are located as far away as 100 kilometers where storage for several months is possible. Onion production has expanded in recent years to Shendi and to the Gezira Scheme.

Preparation of irrigation channels and planting beds for onion cultivation beyond the Nile flood plain in the distance. Wad Basal. Photo by Rick Bein 1975

Preparation of irrigation channels and planting beds for onion cultivation beyond the Nile flood plain in the distance. Wad Basal. Photo by Rick Bein 1975

6. Egyptian and white beans zone occupies the hinterland area around Shendi and as far as Dongola in Northern Province. Beans are not bulky and can easily be stored for months before shipping them to market. Wheat is also grown in this zone and comes from Northern Province and the Gezira Scheme.

Beyond the first zone of land use to the south of Khartoum, the zonation does not fit the same pattern found in the north. This is because of the dominant control of the Gezira Scheme and other government agriculture schemes. Cotton is produced here for export, but groundnuts, sorghum, wheat and sugar are also produced in the same area for Sudanese consumption. These are shipped to Khartoum when available, and because of their transportable nature and the comparatively greater distance to Khartoum they could be categorized in zone 6.

The zonation stops here for the provision of food stuffs to the Khartoum market, although additional zones might be defined for serving other needs of Khartoum. For example, fuel in the form of charcoal comes from forests in the Gedaref area near the Ethiopian border. This, however, is related to a resource availability factor and not to ease of transportation.

Fruits such as mangoes, dates, guava and citrus are difficult to locate within this spatial scheme because they are seasonal and market demand in Khartoum can not be satisfied. Therefore, cost of transportation becomes less of a factor of location and factors of soil and climate become more influential. Fruits brought to Khartoum come from great distances like Jebel Marra, Kassala. Northern Province and even southern Sudan. On the other hand, some are produced within a few kilometers.

Intensive use of the land occurs near Khartoum where multiple cropping is practiced in the Nile flood plain. The products more easily stored and easily transported are found being produced at a distance of over one hundred kilometers.

Conclusion

This paper illustrates the effect of transportation on land use with respect to the Khartoum hinterland. Only the land use influenced by transportation has been analyzed, although many other factors influence land use.

The concept of the Von Thunen model applies to the land use along the Nile with respect to the Khartoum market. Moreover it seems that the Nile farmers within the Khartoum hinterland are “economically minded” with respect to crop production. As a measure of efficiency with transport facilities constant, the existing cropping areas are in economically viable locations. Apparently this land use pattern has existed for several generations and has become adjusted to the transport system. For the purpose of agricultural planning it would be wise to look carefully at the existing peasant agricultural systems before making decisions. Also the effects of transport changes such as expansion of asphalt roads are likely to bring changes in the land use pattern

Extension of asphalt roads. for example. to Dongola in northern province or Kassala in the east, would make possible regular transport to the Khartoum market for crops grown in those areas. This could possibly cause expanded production of wheat and Egyptian beans in the case of Dongola. and durable fruits in the case of Kassala. The growing areas would extend further from Khartoum the more transportable products such as Egyptian beans, which would free areas of intermediate or closer proximity to Khartoum to produce more perishable goods. Kassala is one of the main fruit producers for the Khartoum market in spite of its being 500 kilometers distant. This anomaly can possibly be explained by the rich soils and cooler climate suitable for high fruit yields. Labour costs are much lower in Kassala than in Khartoum which also helps compensate for the greater transportation costs.

The growth of Khartoum will affect, as it has in has in the past, the crop growing area. Increasing demand will cause cultivation to increase, but along the Nile the area is limited. The.expansion, therefore, is in areas of adequate water even further from Khartoum. Examples of this are:

I. Potatoes which are now also grown in the far west around Rebel Marra and in Northern Province. –

2. Wheat has expanded its production area to the Khashm el-Girba Scheme.

3. Banana production is being increased at Kassala.

4. Egyptian bean and white bean production is being expanded in Northern Province.

5. Vegetables such as bell peppers and tomatoes are now being grown in the Gezira Scheme for the Khartoum market.

One could possibly argue that the land use zones observed around Khartoum are the results of economic forces of the past and are merely historic features of the landscape. Although traditions hold the pattern together, land use. it must be remembered, is dynamic and over time will respond relative to the forces of progress or stagnation.

Appendix

I determined ease of transport by rank after observation of transportation, storage and marketing facilities. Greens, the leafy vegetables consumed in salads or in soups. are extremely bulky and must be consumed within 24 hours after harvesting. They are also easily damaged and must be carefully handled when bringing them to the market. Usually they are brought loosely in open trucks or carts from short distances. –

Alfalfa similar in texture to the greens was considered less difficult to transport, as less care is taken in handling because it is fed to animals.

Vegetables, as a general category. are perishable but can wait from two days up to two weeks before being consumed. The degree of perish-ability varies with different types. These include carrots, beets, bell peppers. squashes. and green beans.

Bananas are generally perishable, but are cut green and carried in open trucks to market. As much as two weeks can pass between harvest and consumption.

Fruits such as citrus and mangoes are perishable and without rough treatment are consumable up to a month after harvest. They are easier to store and less perishable than vegetables and bananas, but more so than potatoes and onions.

Potatoes and onions are similar in trans-portability as they can be stored more than six months after harvesting and can be packed into sacks and endure rough overland trips. Potatoes are considered more difficult to store than onions as native technology has been more successful in keeping the onion dry in well ventilated huts.

Wheat. groundnuts. Egyptian beans and white beans can be stored up until the following year with little difficulty. It would seem that the beans are more durable than groundnuts and wheat because the beans have greater resistance to insect damage. Wheat as it is stored here can be infested with weevils, while groundnuts stored with shells intact are better protected. Egyptian beans and white beans are virtually the same with respect to storing capacity and perish ability. White beans are slightly smaller in size and more compact and therefore the airspace between them is reduced. The Egyptian beans being more elongated are considered more bulky as a result of greater airspace and therefore are more difficult to transport.

References

Abdalla. A.A.and M. C. Simpson: “The Production and Marketing of Vegetables in Khartoum Province”. Research Bulletin No. I. Information Production Center. Department of Agriculture. Sudan. December. 1965.

Altaweel, Mark Von Thunen Land use patterns. Agricultural Geography, December 16, 2020.

Barbour. K. M. The Republic of the Sudan: A Regional Geography (London: University of London Press Ltd.. 1961).

Chisholm. Michael: Rural Settlement and Land Use: An Essay in Location. New York: John Wiley and Sons Inc.. 1967.

Cole. John P. and C. A. M. King: Quantitative Geography (New York: John Wiley and Sons Ltd.. 1968).

Mohamed. Yagoub Abdalla: “Land Use and Rural Settlement in Khartoum Province”, unpublished Masters thesis. University of Khartoum, 1970.

Worall. G. A. “Soils and Land Use in the Vicinity of the Three Towns”. Sudan Notes and Records, 39 (1958). pp. 3-10.