48 Feasting with the Nyangara in southern Sudan

Rick Bein

About 50 kilometers north of the Uganda border a small crowd of Yanguara tribesmen from southern Sudan hungrily watch, politely waiting for me to do something. A large bowl brimming with roasted flying termites (Macroterms spp.) sits before me. I pride myself with being able to eat almost anything that someone else can eat, but insects? They look like dark reddish brown half inch sticks with wings sticking out.

I am thinking: “This is not the going to be easy!”

Termite preparation by Mercy Uchenna YouTube 2008

Termite preparation by Mercy Uchenna YouTube 2008

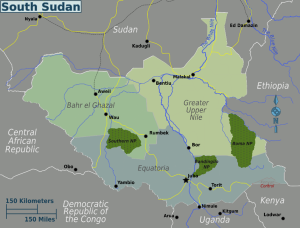

South Sudan regions map.png by Peter Fitzgerald is licensed under CC BY 2.5

South Sudan regions map.png by Peter Fitzgerald is licensed under CC BY 2.5

“Patrick, what am I supposed to do?” Patrick Ladu, one of my students from the University of Khartoum is very patient with me. His tribesmen are also patient.

“Take a few off the top of the pile and put them in your mouth! You are the guest of honor and you must eat first. No one will eat until you do! This is a delicacy as they have prepared the very best for you!”

Mustering my courage, I pick a couple of large two-centimeter-long bugs off the top and before I can change my mind, put them in my mouth. Immediately the crowd dives into the community bowl of termites, filling their mouths with ecstasy.

I am overcome with their delight at what they are eating, forgetting what is in my mouth, and I begin chewing. To my amazement, I find the termites pleasingly salty with a pretzel like texture. I try to grab a few more, but that is my last bite as the pile disappears in the frenzy!

This is an East African delicacy that is craved for its saltiness. The heavy tropical rains of Southern Sudan, Uganda and Western Kenya wash most of the natural salt out of the soil. As a result the salt content in plants is also low. Termites obtain minerals found deep in the subsoil where they dig their burrows and salt being one of them is concentrated in their bodies, making them a high demand item by the local people as they seek to meet the salt deficiency in their diet.

In the mid-1970s they were a great snack food. People walked around the East African markets with paper cone wraps full of roasted termites munching as they went along. Instead of eating popcorn at the movies, they snacked on termites!

When I returned to Kenya in 2007, I noticed very few people eating termites and those that kept the habit were in small villages.

African termites build huge hard clay mounds up to ten feet high in which they live. They process decaying vegetative material in the soil, eating the plant material and depositing the mud-like material to form the mound. In this area of Africa, termites are welcome and when a new termite mound starts to appear, the first person to see it puts a claim on it along with the right to collect them.

Termite mound with author, Photo by Rick Bein 2012

Termite mound with author, Photo by Rick Bein 2012

Some of the termites swarm in the evening following a rainstorm and fly off to start a new colony. The local people know when this is going to happen and just before dark, dig a shallow rectangular hole measuring fourteen by fourteen inches square and about two inches deep at the base of the mound. In the middle of this small pit a candle is left burning and when the termites are attracted to the light, they burn their wings and fall into the shallow pit. In the morning the pit is full of crawling termites which the owner collects.

Over the next few days, I have many chances to eat termites. Besides roasting them, they are fried, baked, broiled, boiled or made into meatballs. A recipe book could be written!

I Actually started to become accustomed to the salty flavor of the termites. The one thing I did not get used to, was the wings and antennas catching between my teeth that poked out when I smiled!

I found that the Nyanguara used their shifting cultivation fields as bate for wild animals. They set snares at the entrance to the fields. One day a Thomson Gazelle (Gazella thomsoni) was caught and although it was a rather small critter, it was easily made into a meal for a couple of families.

Gazelles grazing, Photo by Rick Bein 1976

A one-ton cape buffalo (Sycerus caffer) was caught a few days later. The huge carcass was shared far and wide throughout the rural area. Even then the people could not eat it fast enough. With no refrigeration, the meat began to spoil. Being conservative with their resources, the people did not want to waste it and kept re-cooked it even as it turned rancid. Yet, the buffalo meat sat in the stew pot over the cooking fire. When the fire went out at night, the meat continued to decompose.

Watering place for the Buffalo. Photo by Rick Bein 1976

At first, I enjoyed eating buffalo, but after a few days it began to taste bad. I was not sure who was going to eat it first, me or the maggots.

Finally, I said. “Patrick, I cannot eat any more of this buffalo, I think we should leave and go on to visit some more of your relatives.”

Patrick agreed and the next day we set out walking. Ten kilometers later, it was mid-day and we stopped at a village just in time for lunch. Lunch, you guessed it, was another shared portion of that same rotting buffalo!