47 Dry Land Water Management: Two Case Studies Sahelian Sudan and Colorado Piedmont

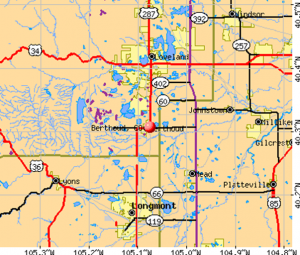

I grew up in a water short environment. We lived in Berthoud, Colorado, 45 miles north of Denver between Longmont and Loveland. Our farm was two miles east of town with a full panorama of the Rockies to the west. Berthoud receives fifteen inches of rain per year on average, most of which comes from snow. This amount of water is inadequate for most agriculture and certainly not enough for our rotated crops of sugar beets, corn, alfalfa, barley, pinto beans, and cucumbers. Our irrigation water was provided by the snow melt from the 14000-foot-high mountains. We always knew about how much water we would get by the amount of snow that we could see on the mountain tops. When there was little snow, we knew we would have a difficult year.

Berthoud, Colorado is shown midpoint on the above map. The Big Thompson River follows Highway 34 as it comes onto the map from the west and continues through Loveland. The water is diverted into some large lakes northwest of Berthoud.

The amount of winter snow on Mt Meeker and Longs Peak indicates the amount of water for farming. Photo by Jean H. Bein 1950.

The amount of winter snow on Mt Meeker and Longs Peak indicates the amount of water for farming. Photo by Jean H. Bein 1950.

From the early settlement in the 1860s, Irrigation water was a concern and was allocated sparingly based on a system of water rights acquired on a first come basis. The earliest settlers claiming a share of the water were served first each year and if there was adequate snow in the mountains everyone had water. These water rights could be bought, sold, or leased between farmers as long as the water was used for agricultural purposes. In essence, water was more valuable than land. A newcomer had to not only buy land but had to buy water along with it.

Water was diverted from the rivers and stored in reservoirs along the foothills and then distributed through a network of canals and ditches that delivered it to the farms. The Handy ditch delivered our water from the Big Thompson River.

Siphon tubes bring water from an irrigation ditch in to graded furrows between rows of Sugar beet plants. Photo by Jean H. Bein 1955.

In the late 1800s the competition for irrigation water was severe and farmers found themselves stealing water and getting into physical fights. The trans-mountain Big Thompson River diversion project completed in 1910 eased the shortage of water. The construction of the Adams tunnel, a nine-mile-long aqueduct, diverted water from the Colorado River on the western slope dumping it into Lake Estes on eastern slope in Estes Park. An annual average of more than 220,000-acre feet of water supported farming eastward as far as Greeley. Since this occurred at such an early date, many of the subsequent water demands to the west could not be met. An acre foot of water translates to “water a foot deep covering one acre of land.”

Ground water was not an irrigation option since it was limited in volume. It was very alkaline from the farm chemicals seeping into it. As a source of drinking water, it became more and more toxic as technological inventions were advanced. We drank that water for a while but stopped drinking it in 1948 when the taste became disgusting. Instead, we trucked mountain water to a cistern once a month. We rationed our household water, never allowing a tap to run or drip. We delayed flushing the toilet when it only contained urine. Sometimes we even shared bath water.

However, we allowed the livestock to drink the hard water. The beef cattle seemed to be managing, but a few years later in 1955 when a rural drinking water project piped potable water to all the farms, the beef cattle performed much better. Sores on their backs stopped occurring and their growth rate increased. The milk cows produced more milk. I do not remember if we experienced any ill effects from drinking that milk prior to the new water system. Maybe we were just lucky.

The land that was out of reach of irrigation ditches, we called dry lands and used them for grazing cattle and growing winter wheat. Winter wheat was planted in the Fall and was harvested in June. We strip cropped this, alternating plantings one year to the next. The fallowed strip held enough water to contribute to the next years planting. We captured snow melt in a small reservoir for the cattle.

My next experience with a water-short environment was in the Sahel of the Sudan. The Sahel is the band of semi-arid land along the southern edge of the Sahara Desert. Here, the average rainfall is about four inches near northern edge of this band and the southern edge receives is twenty inches. With the average temperature of 95 degrees Fahrenheit the rate of evaporation is extreme.

Map of Nile down from Khartoum by Chris Lett, July 2019, Creative Commons Licensing Chris Lett. The Nile flood more than compensates for the arid climate as it has supported civilizations for nine thousand years and is still the dominant water supplier for Sudan. This irrigation farming is sustained by the annual floods of the Blue Nile that descend from the Ethiopian highlands during their intense rainy season. The silt that it carries is deposited along its banks. Most years the flood supplies water for farmers to pump onto their fields, but every 5 or 6 years the Nile flood reaches beyond the banks to enrich the entire flood plain. Crops grown are wheat, barley, onions, dates, grapes, plums, melons, and vegetables. Livestock adds to the diversity. Goat and cow’s milk provides sustenance to most households.

Map of Nile down from Khartoum by Chris Lett, July 2019, Creative Commons Licensing Chris Lett. The Nile flood more than compensates for the arid climate as it has supported civilizations for nine thousand years and is still the dominant water supplier for Sudan. This irrigation farming is sustained by the annual floods of the Blue Nile that descend from the Ethiopian highlands during their intense rainy season. The silt that it carries is deposited along its banks. Most years the flood supplies water for farmers to pump onto their fields, but every 5 or 6 years the Nile flood reaches beyond the banks to enrich the entire flood plain. Crops grown are wheat, barley, onions, dates, grapes, plums, melons, and vegetables. Livestock adds to the diversity. Goat and cow’s milk provides sustenance to most households.

Farming the Nile floodplain. Farmers use diesel pumps to send water to irrigate floodplain crops of millet, sorghum, and date trees on the edge of the desert. Photo by Rick Bein 1974.

Away from the Nile, farming continues under harsh conditions as farmers manage to grow the arid land crops of sorghum, millet, and okra. This rain-fed agriculture is quite tenuous, depending on two or three rainstorms for a successful crop. A good crop year occurs once in about five years and there is enough grain to supply those four extra years. This region, known as the Sahel, borders the southern edge of the Sahara Desert and extends east and west across Africa. Nomadic herding of cattle, sheep and camels is more flexible as the mobility of the herds allows them to seek areas that have been watered.

Convective rainstorms arrive in the summer months of June, July, and August. Convective storms are isolated thunderstorms that occur in spotty patterns, where solar heating thins the air. This lighter-weight air rises and cools until it condenses. Not all areas receive rain at the same time. Hopefully, those villages that do not receive rain initially will get rain later in the season. These rainstorms will usually provide an adequate crop of sorghum to support the community for the year. If not, grain stored from more productive years will suffice.

A successful crop year provides enough sorghum grain for several years. My students accompany me to witness the children guarding threshed grain from birds. Surplus grain will be buried in underground silos. Sorghum in the background is ready for harvest, while piled up chaff will be set aside for roofing, weaving, and bedding. Photo by Rick Bein 1975.

Many communities struggle year to year. As global warming continues, the Sahel is shifting southward, and more desert like conditions are taking over. Droughts come and go lasting years at a time. The government has tried to help these unfortunate communities by constructing wells to bring water up from the Nubian Sandstone aquifer. The wells have served as a safe source of drinking water and given the villages some stability. Water is drawn with ropes and buckets, a time-consuming task. Various contraptions have been arranged to make this job easier.

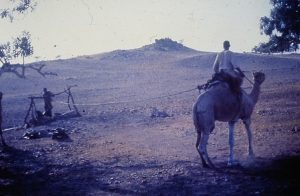

A nomad uses his camel to pull water out of a well while Villagers contaminate a second well with poor practices. Photos by Rick Bein 1975.

It was not until investments in diesel pumps made it possible for substantial amounts of well water to be designated to irrigate crops. It was then that the limitations of the aquifer became an issue. Now water uses must be prioritized.

Still the village well is the most significant part of the village life, not only as a source of water, but as a social gathering place for women who carry water back to their homes. Without the well there would be no village. In some cases, the wells are not well maintained, and water pollution contributes to intestinal diseases. Over time, with education, some of these problems have been remedied.

Wells further out toward the desert supply water only to the nomadic herds. These served as stations where the nomads can stop off to satisfy their thirsty livestock. As livestock is their main source of wealth, increasing herd size has led to depleting aquifers.

The demand for water for the nomadic herds has become a source of conflict at the village level. Potable water is a problem over large spans of desert where only saline water can be found. Desperate nomads have no qualms about encroaching on a village water supply.

One unique water source is the Rahad River, a little recognized source of the Nile. It joins the Nile 200 miles north of the confluence of the Blue and White Niles (near Meroe on the map) but contributes water only during the rainy season. During the dry season, some of the deeper meanders hold water for a couple of months.

That water is a source for some nomadic groups who camp beside it. Unfortunately, these ponds become extremely polluted with the waste from the animals and people. Schistosomiasis parasites prevail as well as many types of bacteria. Children play amongst the cattle, all enjoying wading in the water. The women have devised a technique to collect drinking water. Alongside the standing water, they dig small depressions four inches deep in the silt. Water seeps laterally through the one foot of silt into the small pool. They think that the one foot of silt is enough of filter out any parasites. I decided not to try it.

As the pools dry up on the bed of the Rahad River, new water filtration holes must be dug closer and closer to the water. Photos by Rick Bein 1974.

Overgrazing is also problematic as the area around the wells have become stripped of vegetation for miles around them. Wells can be spotted from high in the air as bare five-mile radius circles dot the landscape.

A contrasting example occurs in the Butana Sahelian zone where no aquifer exists and only camels can graze as they can survive long times without water. With no competition from sheep or cattle, the camel nomads can manage their environment very wisely. It might be of note that the camel graze desert bushes by plucking tiny succulent fruits from in among the thorns.

The succulent fruits contain enough water to support small herds of camels indefinitely. The camel herder obtains his water by drinking fresh camel’s milk.

Environmental limitations have been encountered by many diverse cultures. Each has its own solution. One ancient system of arid land management still survives, while this more modern system also prevails. Water is the basic necessity for survival, and the management of water is also critical for every society.