42 Soil and its Impact on Culture: A Case Study in the Sudanese Sahel.

Soil and its Impact on Culture: A Case Study in the Sudanese Sahel.

Soil is the basis of human survival and adaptations to it occur in a multitude of ways. Soils are created by nature through the processes of the breakup of rocks, climate, living organisms and time. This is referred to as “weathering.” When these different processes combine, a multitude of soil types are produced. Humans have learned to survive, using their soils for food production, building materials, medicine, and art.

Major soil types of Sudan, Sudanese Soil Information (SUSIS) 2016 Free map from Sudanese Land and Water Research Center. Vertisols are represented by color red designated as Vertic Haplocambids.

Major soil types of Sudan, Sudanese Soil Information (SUSIS) 2016 Free map from Sudanese Land and Water Research Center. Vertisols are represented by color red designated as Vertic Haplocambids.

The focus of this treatise is to examine the relationship the people of the Sudanese Sahel have with their difficult to manage vertisol. This soil shrinks and cracks when dry, when wet it expands and bulges. It does not hold much water and once wet, seals the ground to any downward percolation of water.

Vertisol, a soil order described in the (7th Approximation of Soils 1960) that occupies 16% of the area of Sudan, is better known as black cracking clay, occurring in many countries and is known by local names such as “black earth” in Australia,” black gumbo” in East Texas, “vioi soil” in South Africa, and bentonite clay in the USA. In the Great Soil Groups classification, it is known as montmorillonite. In Sudan, they are known as “black cotton clays”. Chemically it is made up of hydrated aluminum silicate. Science taxonomy divides the vertisols into sub-categories depending on the size of the cracks that occur and the length of time between shrinking and swelling periods. The Sudanese vertisols are labeled “usterts.”

Climatically, vertisol occur where there are pronounced wet and dry seasons. In the Sudanese Sahel, the dry season lasts August to April when the water evaporates and the soil shrinks, leaving cracks up to a half inch wide.

My keys provide a sense of crack size of a vertisol sample. Photo by Rick Bein 1977

My keys provide a sense of crack size of a vertisol sample. Photo by Rick Bein 1977

When the rains come, the soil swells and tries to close up again, but the cracks are now already full of debris and instead, the swelling process expands upward leaving chunks of soil protruding over the flat landscape. The dead plant material trapped inside decomposes, and over centuries of time, darkens the soil.

A stabilized sand dune is perched on top the dry-season black cotton clay plain. Clumps of soil (gilgai) protrude over the clay plain and a primitive road has compacted the slightly dampened clay. Surface water on the clay evaporates quickly while the dune holds enough water to sustain the sparse vegetation

.

Once the wet vertisol closes its cracks there is no more downward seepage and water is trapped on the surface.

Once the wet vertisol closes its cracks there is no more downward seepage and water is trapped on the surface.

After each rainstorm, this volatile landscape becomes a quagmire, and any travel is hampered by slippery mud clinging to feet and motor vehicle tires. Dirt roads disappear as ruts are incorporated into the gummy landscape. Any asphalt of concrete roads will crack and break but will be passable at slow speeds. In preparation for the rainy season, villagers stock up with food and anything they will need during that time.

Sorghum and millet are drought resistant and provide cereal sustenance for most of Africa.

Farmers plant sorghum and millet before the beginning of the rainy season, hoping for sufficient rain. Even during the rainy season, rain does not always come, and the villagers must depend on grain harvested from more successful crops in previous years.

The underground grain storage is incredibly unique, dating from Pharaonic times. The shrinking and expanding nature of the vertisol protects grain buried eight inches under the soil. Matmuros, one-meter-deep pits, dug on the outskirts of villages protect the grain from moisture. A cover of the expanding clay blocks water seepage. Two tons of grain can be stored this way.

The matmuro can keep grain for up to seven years. A thin layer of grain chaff insulates the grain from mixing with the soil. Over the chaff an eight-inch layer of soil will expand when dampened to prevent rainwater from penetrating below four inches. The chaff is easily separated when the grain is winnowed after it is collected. Photos by Rick Bein 1975

Grain stored up to seven years is located far enough away from the village to keep the rats from digging into the grain. The village dogs who feast on the rats will keep them from crossing the three hundred feet to the matmuros. Those pests that do make it to the matmuro find there is no water for their survival. After a seasonal rain, the matmuros are imperceptible and only those that placed them there know where they are located. Following a good crop year, which occurs once in five years, a number of matmuros form a ring around the village. The farmers estimate that about 10% of their grain is lost to spoilage. This system also protects the food from marauding tribes, and should the villagers have to flee, the grain will be waiting when they return. The farmers should be returning now (2022) that President Omar Bashir has been deposed and his vigilantes he sent, have since gone home.

Close to the Nile, within reach of irrigation, farmers retain water on their crops by constructing small flatland terraces (terus). The terus, made of the vertisol clay, are temporary and can easily be shifted to guide water in and out of the enclosed plots. These terraces help retain water, preventing it from running off. Where the slope is gentle, the farmers mound up terraces on three sides of a field with the open end facing up-slope. A small catchment is thus created, and more runoff water can be captured than would normally fall on the field. Often these mini-catchments can hold enough water to irrigate several fields. After soaking the first field and giving the plants a watering, an opening in the terrace allows water to flow to the next field.

In Wad Basal, Sudan a Koranic school master (Faqui) teaches boys 3-8 how to grow onions beyond the distant Nile date palms. Water is pumped into the small channels that flood the plots after the onions are transplanted. Photo by Rick Bein 1975

In Wad Basal, Sudan a Koranic school master (Faqui) teaches boys 3-8 how to grow onions beyond the distant Nile date palms. Water is pumped into the small channels that flood the plots after the onions are transplanted. Photo by Rick Bein 1975

Nile water is pumped out to the desert, feeding through a maze of channels to irrigate small plots of onions. Photo by Rick Bein 1975

Nile water is pumped out to the desert, feeding through a maze of channels to irrigate small plots of onions. Photo by Rick Bein 1975

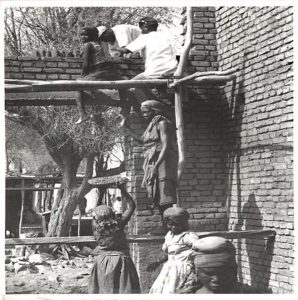

Rick Bein sits with villagers beside a sun baked brick wall in Genena, Darfur. Kiln baked bricks are used for this building. Photos by Rick Bein 1975.

Rick Bein sits with villagers beside a sun baked brick wall in Genena, Darfur. Kiln baked bricks are used for this building. Photos by Rick Bein 1975.

Buildings constructed on vertisols are at risk as the soil shifts back and forth causing the foundations to collapse after a few years. To prevent this, Sudanese villages go to great lengths to keep the footings of their buildings dry. During the rare rainstorms, covers are placed around their structures. When I planted a vegetable garden in the area around my house, the landlord came and pulled up all my plants. He explained that the water to irrigate the plants would also affect the foundation of the house.

In some areas far from the Nile, vertisol clay bricks are used, but the quality is poor. The expansion and shrinkage of the clay make it extremely difficult to use. Kiln fired vertisol soils can be made into suitable bricks only if they are kept dry for a lengthy time under the shade of a drying shed. Sun-baked vertisol bricks disintegrate after about two years.

Bricks made from Nile silts were traditionally used in the Sudan, but this has depleted the soils of the rich agricultural flood plain and the government has created laws preventing the practice. Today the Sudanese are looking for new ways to process the ubiquitous vertisols into bricks.

References Aylmore, L.A.G. & Quirk, J.P. (1959). Nature 183 1752. Biswas, T.D. & Karale, R.L. (1974).

Bein, F.L. Response to drought in the Sahel “Journal of Soil and Water Conservation, vol. 35, vol.35, No.3 1980

Dregne, H.E. (1976), Soils of Arid Regions, Developments in soil science six, Elsevier, New York.

Dudal, R. (1965); Dark Clay Soils of Tropical and Subtropical Regions. Agric. Dev. Pape 83, FAO, Rome.

Hamid, M.H “Brickmaking Industry in Sudan” Prepared for forestry National Corporation (FNC) and (FAO)1989.

Hamid, M.H” Comparative study on Rational use of fired-clay in building in Khartoum” Ph.D. Thesis, Building &Road Research Institute U of K 1987.

Major soil types of Sudan, Sudanese Soil Information (SUSIS) 2016 Free map from Land and Water Research Center. Vertisols are represented by color red designated as Vertic Haplocambids

Rash Abd Elslam Elsharrif “Quality of bricks produced from non-conventional clay” MSc Thesis in building Technology, University of Khartoum, 2007.

Seventh Approximation of Soils, Natural Resource Conservation Service, USDA, 1960

Worrall, G.A. Features of some Semi-arid soils in the district of Khartoum, Sudan: The High-level Dark Clays, Journal of Soil Science vol.8. No 2. (1957).