60 Spirits of the Forest

While I was directing the Environmental Research Management Center and teaching Environmental Geography at University of Technology at Lae, Papua New Guinea (1996-99), I took on an assignment with the NGO Village Development Trust (VDT) to develop a transect trail in a village 20 miles south down the Pacific coast.

Map produced by the Central Intelligence Agency 1998, Public domain Perry Castaneda Map Library, University of Texas

Map produced by the Central Intelligence Agency 1998, Public domain Perry Castaneda Map Library, University of Texas

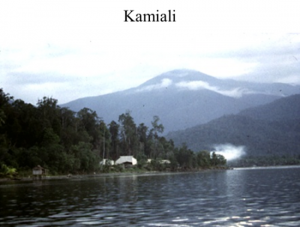

This project was funded by the Asian Development Bank. The purpose of trail was to provide access for Biologists to sample the biodiversity from sea level up through the tropical rainforest and into the cloud forest on the side of a six-thousand-foot mountain behind the village of Lababia. The locals called their village Kamiali.

The Kamiali trail leads westward up the north side of Blue Mountain. Image by Village Development Trust.

I spent a lot of time with the tribal elders (Big Men) gaining their confidence and finding members of the tribe who would like to participate in this exercise. The VDT would pay them some money. Most of the villagers were afraid of the forest because the spirits of the ancestors resided there. Their lives were oriented around the sea and their “food gardens”.

The only ones who ever went into the forest were the hunters who brought game to enhance the village diet. The hunters, Levi, Enock and Tany volunteered to participate. I spent some time discussing what we needed to do. I found that one of them, Levi Ambio who had served in the Papua New Guinea (PNG) National Guard, spoke English and was interested in learning about the mission. We agreed that we would start out the following week. Levi thought that the best way would be to head directly toward Blue Mountain.

Blue Mountain stands behind Kamiali Village. Photo by Rick Bein

Lababia from the air, coconut trees line the beach, food gardens fill the cleared land and forest prevails along the periphery. Photo by Village Development Trust.

The representative from the NGO, Village Development Trust, explains my mission to the community.

I’m looking at Blue Mountain that we were trying to conquer.

On the following Monday, the three hunters and I headed over a ridge south of the village. Levi, the lead hunter, told me that this was the valley belonging to the Massalai (ancestral spirits) and that villagers were afraid of being there, let alone living there. Somehow my presence made it safe for the hunters to be there, maybe because they thought that I was not afraid.

We set up camp there to ready ourselves for the hike the next day. We found a good space in the rainforest to hang our hammocks built a cooking fire, ate and went to sleep. In the middle of the night Levi started screaming and churning in his hammock. I reached over and woke him and asked what was happening. He said he dreamt that a Masalai was attacking him. He then went to sit by the fire when one of the ancestors asked him about the purpose of this white man coming to their territory. Levi told him that I was ok and that I was here to help the people. Apparently, the ancestor was alright with this and Levi explained to me that I was welcomed there.

Levi contemplating the Masalai at the campfire. Photo by Rick Bein

Levi contemplating the Masalai at the campfire. Photo by Rick Bein

Blue Mountain was at the head of the valley and as we headed toward it, I looked ahead, it appeared that we were coming to very steep cliff that would be too challenging. I suggested we take an easier longer route by heading up the ridge that circled around the north side of the mountain. The hunters readily agreed because that would take us along the edge of the ancestor’s territory as the ridge was the northern border of their domain. We proceeded up along the ridge cutting a slit through the forest with machetes, one man at a time. One person would cut, swinging his machete as rapidly as possible until he was tired, then the second man would take over. I even tried my had at cutting with the machete, but they quickly took it away from me and told me that I was too dangerous and might cut myself or one of them! They took me back behind the group and handed me my camera saying this was where I belonged. We slowly progressed up the hill for about a mile the first day, then camped and ate some of the provisions that VDT had given us. As we were gaining in elevation the temperature cooled and sleeping in hammocks was too cold. The next day we sent Inok to return down the trail to request some tents. Later that day a fellow brought us a note etched into a piece of bamboo to let us know that a tent had been delivered.

Note etched into this piece of bamboo alerted that a tent was left at our last camp. Photo by Rick Bein 2021.

Note etched into this piece of bamboo alerted that a tent was left at our last camp. Photo by Rick Bein 2021.

A Carnivorous Pitcher Plants catching insects.good look at the ground level of the rainforest. Photos by Rick Bein 1998.

We continued for a few hours the next day and we decided that we should leave this for my next trip down from the town of Lei. After several days I returned, and we continued cutting through the forest. When we reached the elevation of about 3000 feet Tany, the person who was currently swinging the machete, stopped and turned around with a terrified look on his face and ran to the other two hunters talking rapidly in their Kela language. I know something was wrong and I inquired of Levi.

Levi said “Tany saw a masalai and thinks we should abandon this project.

I looked at Tanny and asked “What did the masalai look like?”

Tanny replied “He was wearing animal skins and was carrying a stone axe.

I asked “What did he say? “

“He looked at me, we can’t go any further!”

I asked, “Then what did he do after that?”

He said “The spirit disappeared into the forest right where we are cutting, we can’t go on!”

This was very worrisome that we would have to stop this effort and I thought for minute. “Why do they always think of the spirits as being fearsome and negative?”

I then asked, “Could it be that the Masalai was showing us the way?” Suddenly the mood of group changed as they realized what I said could be true. Levi convinced the other two that this was alright, and the ancestor was only trying to help us.

What a relief! We continued cutting the trail with no more apparitions. Two hours after this we decided to make camp for the evening.

They had seen the Masalai as something to fear and to suggest that they were trying to help was something different. In this sense, I might have corrupted their cultural traditions governing the way they behave around the ancestors. On another level, maybe the Masalai was trying to protect his forest from intrusion and nothing good could come from clearing even a trail that could ultimately lead to exploitation and destruction of the pristine environment.

It comes to mind that the local environment is not just the biota, but the integration of the plants and animals, humans, art, sacred sights, water, underground resources, supernatural beings, and others. These are not separate entities as the ontological value allows the full cultural-environmental relationship to continue. This is threatened by outside influences and interests that focus on one the elements. Economic development focusing on mining, logging, intensive agriculture, or even religious and educational efforts.

Things went well during the night, and we pursued our mission the next day. As we entered the cloud layer that surrounded the top of the mountain at about 4000 feet elevation, it became misty and cool. We encountered a very unique fern forest. The temperature slowly dropped down to 60 degrees Fahrenheit. This was alright while we were working and warm from exercise, but when we stopped for the evening, the villagers had never felt such a cold temperature. For me it was a bit of a relief from the 80- and 90-degree temperature down on the coast, but when we started to sleep the mist turned into rain and became unbearable. We were unable to escape the weather. We struggled through the night and in the morning, they convinced me that we had to go back down the mountain.

After that I could not convince them to return to creating the trail. They believed that the ancestors had caused this chill and it was time to stop the project! I resigned myself to this and decided that this was enough trail to provide the biologist with a start to the study area.

As my time in Papua New Guinea was expiring, I was able to escort one biologist who came to pursue his interest in horseflies. Jim Goodwin netted one undescribed horsefly right away but found he could not catch any more unless there was some mobile bait to attract them. Jim convinced me to walk in front where I could be the bait and when the horseflies landed on my back, they would not have enough time to bite me because he would net them first. For a while that worked but one time, he was a little slow and I yelled “Hurry up Jim!” He was too late, and I got a big welt from that that lasted a few days! Jim now had to find some other way to capture his bugs.

As it turned out he was able to identify a new species of horsefly (Cydistomyia (Diptera, Tabanidae) which he ultimately reported to the world of entomologists. I guess I can claim to be its primary bait.

In 1999, I had to leave Papua New Guinea as my time away from IUPUI, my University in Indianapolis, had expired. I had to abandon role with the VDT and Lababia. Many biologists continue to publish their findings from the mountain.

I was able obtain some funding to return to Papua New Guinea the summer of 2000 to carry out my own research on the traditional agriculture that the Kamiali people practiced.

I immediately visited Kamiali where Levi was very happy to see me! He told me that the villagers had missed me. I am not sure if that meant the Massalai also missed me!

But when I went to study and record the GPS of their garden sites in the Bitoi River Delta, the farmers were a bit uneasy. Sure enough, the night after I took the banana boat back to Lae a huge storm produced a terrible flood of water descending the Bitoi River and destroyed all their cassava, sweet potatoes, bananas and taro. That was considered my fault because the spirits did not like me invading that space. The villagers told me the GPS machine irritated the Masalai who caused the flood to happen.

Levi, wife and child exam the remaining sweet potatoes. Photo by Rick Bein 2000.

Now the villagers had to eat starch from inside the sago palms until more vegetables matured. The interior of the tree is pulverized and produces significant carbohydrate and fiber. Locals consider it a famine food that they harvest during these rare occasions.

Preparing famine food from the pulverized interior of the sago palm. Photo by Rick Bein 2000.

The masalai are very much a part of the Papua New Guinea life. Whether for good or bad they respect the ancestors. Many decisions are made after they have listened to the ancestors.

Maryellen, my wife had a sixth sense which she used to plant and arrange the vegetation around our new house on the campus of UNITEC. The Papuans congratulated her because her arrangements included masalai indicators that would deter prospective rascals and robbers from invading our property. As it turned out, our house was the only one of the six houses built by the Asian Development project that was never robbed! She planted a number of shrubs that a local woman gave her, and she used her intuition to locate them around the yard. We were told that those plants and her arrangement protected the house.

Our House on the UNITEC campus in Lei, Papua New Guinea.

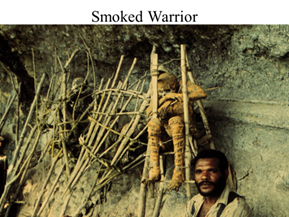

Mummified ancestors can be consulted. Photos by Rick Bein 1999. This fellow introduced us to his grandfather.

Mummified ancestors can be consulted. Photos by Rick Bein 1999. This fellow introduced us to his grandfather.

In honor of the ancestors the Papuan would often carve images of what the ancestors looked like. These icons were used to protect themselves and to threaten their enemies. Currently the masks are being used to celebrate their culture and to impress tourists.

In one community, the tribal warriors are honored by having their bodies mummified and kept dry under a rock outcrop. This fellow told me his grandfather was behind him and was always looking out for him. See image above.