46 Aspects of Sudan in mid 1970’s

Rick Bein

Aspects of Khartoum in the mid 1970’s

The Sudanese people are some the most genteel people on earth. As a white foreigner, I was given great respect and kindness. (Being white, I was given undeserved preferential treatment). I was welcomed into their homes and given tours of their towns and farms. I felt that I was given kindness that exceeded what they gave their own people. Being in Sudan was one of the joys of my life. I arrived with my family in late in the summer of 1974 and enjoyed three years teaching and researching at the University of Khartoum Geography Department.

Most of the Sudanese are practicing Muslims and I became quite comfortable being around their devout practices. Six times per day, we would stop for a few minutes so the devout could pray toward Mecca. The Sudanese Muslims are very loving people and do not judge others who are not Islamic. They did condemn those who used Islam as a cover to justify violence. There was a small Coptic community in Khartoum, and a majority of Christian sects in the far south as well as tribal religions in remote areas of the country.

The lives of the Sudanese were not easy as they endured many hardships: floods, droughts, dust storms, food shortages and periodic military coups. Prior to my arrival the most recent coup was led by Jaafar Muhammad al-Nimeiry who took over the government in 1969 to be dictator for 16 years.

Map of the Nile valley by CIA.

In 1955 the British colonial masters left the Sudanese with a democratic self-rule system that lasted for three years, enough time for the people to become appreciative of the democratic process and were distressed when a military coup occurred 1958. This autocratic rule lasted 6 years with much resistance until another attempt at democracy began in 1965. Four years later Numeri took over and was in place when I arrived.

During my three years stay in Sudan (1974-77), I served as a lecturer at the University of Khartoum Geography Department where I heard a lot of discussion about their hopes of reinstating democracy. This expression was allowed on the campus where the free-thinking mission of the University was permitted. It was considered somewhat safe expression if it stayed on campus. Although dissident Sudanese still sent their sons and daughters to the University of Khartoum with the idea, they might instigate a revolution.

https://www.stepmap.com/map/khartoum-YM7l9Z043R

Several military coup attempts occurred while I was there, but none of them were instigated at the University. Even then, when the attempts happened elsewhere in the country the University was barricaded by the army because of its pro-democracy sentiment.

Keeping up with these coup attempts was no easy task. Once while I was driving to the campus with my wife and three year old twins, we were surprised by a military tank heading straight for us. Immediately I told the twins to get on the floor between the seats (Amazingly they obeyed instantly with no whining) and did a quick “U” turn and headed back to cross over the Blue Nile Bridge. I was fearfully grimacing, thinking that at any moment an exploding shell would do us in. Lucky for us nothing happened. But the tank operator probably did not see us a threat or else did not have enough ammunition to waste on a family vehicle. Whatever the case, the coup failed.

On the next coup attempt, we were driving to campus again and as we neared our destination the twins suddenly started crying because their eyes hurt. Then we noticed it too. “Tear Gas!” the military was trying to quell any action from the students. We wiped our eyes and just headed back home again to learn from the neighbors that there was a coup attempt.

That was a good lesson. “Don’t go anywhere without checking with the neighbors”. They always seemed to know what was going on. One major clue about a pending military coup was that the radio and telephones would go dead. The first thing the rebels would do was to cut off any communication to keep the government from organizing against them. Although my Arabic was limited, with no sound coming out of the radio it did not take much to figure out when something was amiss.

Another coup attempt occurred when Muammar Gaddafi of Libya sent a military contingent to Khartoum to overtake Numeri. We had taken students on a field trip down to the 6th cataract and were returning when our bus driver noticed all the traffic was going the other way. Something was wrong in Khartoum! Our driver heard about if from drivers going the other way, but we proceeded cautiously on to Khartoum North where the under equipped Sudanese army had cordoned off access to the Nile Bridges. We could stay in Khartoum North where it was safe. We dropped the students off at the agriculture campus and the faculty stayed at my place. (Fortunately, my family was on vacation leave back in the States).

Since food was forbidden to cross the river into Khartoum proper, we had plenty to eat in Khartoum North. After a week Gaddafi’s starving solders were easily overcome. The people living in the main city had sequestered themselves and refused to share their food stashes with the invaders. Gaddafi’s solders expected the Sudanese locals would welcome them with open arms. That did not happen as people said, “We may have a dictator, but at least he is ours”.

Eight years after leaving Khartoum, I had a chance to return for a short visit in 1985. I went to visit the Geography Department at the University and arranged for a tour to the Gezira agriculture scheme located between the Blue and White Niles. Upon return to the city, I went directly to the airport to catch my flight out. As I arrived at the gate there was news of a military coup taking place and they were planning to close the airport. Fortunately, my plane was the last one out.

This military coup was successful and over-threw Numeri’s 16-year reign. After a series of coups, the new dictator Omar Bashir emerged and reigned until 2019. As a very harsh ruler, a massive persistent movement of civilians forced him to step down. Now there is a transition military-civilian coalition slowing developing a democratic system.

As I arrived to Sudan in 1974 the Geography Department welcomed me warmly and assigned me to teach Environmental Conservation and the Geography of Agriculture. I had just received my PhD at the University of Florida and I was up for the adventure. The University of Khartoum had kindly provided transportation from the States and arranged our living arrangements.

The house where we lived was in Khartoum North across the Blue Nile. It was in a neighborhood called Khobar, a developing area where new houses were being built. An eight-foot brick wall with an iron gate surrounded the house that contained spacious ten-foot-high ceilings and a stairway going to a flat roof. The design was arranged to deal with the extremely hot climate, 100 degrees Fahrenheit plus in summer. The high ceilings trapped air so that the warmer air would rise leaving slightly cooler air on floor. The roof was used for sleeping outside where the nighttime temperatures would drop to a comfortable 70 degrees. On rare occasions a rainstorm or a haboob would appear prompting us to evacuate the roof and seek shelter inside.

Dust storm approaching Khartoum. Photo by Rick Bein 1976.

There was an interesting environmental problem that I had not encountered before. Most of the soil outside of the Nile flood plain is a black-cracking clay that shrinks when it is dry leaving big cracks and expands when wet, closing the cracks. This means that any structures built on it would be impacted by this shifting soil. One way that my landlord dealt with the problem was to keep the soil dry as much as possible and in this arid region rain was not a serious issue. One time when we thought we could grow some vegetables in the compound next to the house, he immediately pulled up all of our plants because the act of watering them would cause the ground to swell.

Black clay swells when wet and shrinks when dry. Photo by Rick Bein 1976.

The university students were very bright as they had been selected at several stages of advancement from grammar school, middle school and high school to be admitted to the only University in the country. They also had to pass an English competency exam since all university subjects were taught in English. That changed some years later to Arabic.

It seems that I broke one of the rules that old British academics had left behind and that was that faculty do not fraternize with the students. Students were held at a distance and were treated rather rudely, it was like a rite of passage, where those who could endure, the humiliation were allowed to graduate.

I worked closely with the students, took them on fields trips, and visited their homes. They explained a lot of their traditions and they tried to teach me Arabic. Fortunately, I was not ostracized for this, as I felt that this was a great way to learn the culture. By chance one of my students later earned his PhD and came to teach Geography at Hunter University in New York City. I ran in to Mohamed Ibrahim at one of the Association of American Geography conferences. He shared with me that my teaching inspired him to become a teacher because I alone at the Khartoum Geography Department, “treated students like human beings”. We still get together at the AAG meetings every year.

My research interest was in traditional agriculture, and it was waiting for me in Sudan. Agriculture was the mainstay of the economy and there was plenty to study. I was intrigued with the land use patterns and the people’s relationship with nature. There was farming on the banks of the Blue Nile that passed right by campus. This farming, called “Gerif” is probably the oldest form of agriculture along the Nile and extends all the way through Egypt. Gerif cultivates the silts that are exposed when the annual Nile flood waters recede. Crops are planted one row at a time following the descent of the water.

The gerif is cultivated every year as the Nile flood waters recede. Vegetables on the left are ready to harvest while plants on the right are being planted. Photo by Rick Bein 1976.

An additional type of farming developed in cultivating the entire floodplain that was productive enough to support the ancient Egyptian civilizations beginning four thousand years ago. It is the high flood that happens about every six years or so, when extra heavy rains in Ethiopia send enough water to immerse the Nile floodplain depositing its precious silts.

The Nile floodplain is covered with silt (in fore ground) when the high flood occurs. The Nile channel is below the picture. The village of Al Uqsur, Egypt is in the desert out of the flood plain. This image precedes the construction of the Aswan Dam holding back the high flood and its silt deposition. Therefor no more silt can be deposited to restore fertility. Photographer unknown

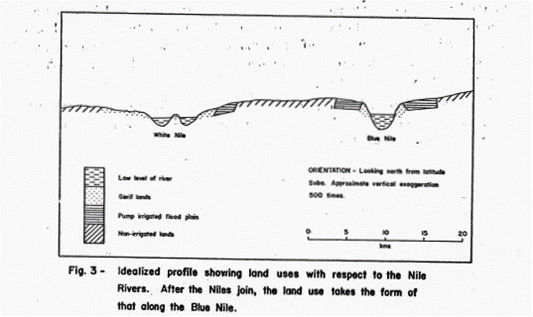

Three types of agriculture plots are shown with the Gerif farming along the sloping banks of the river, shadowed by the irrigated floodplain, and the expanded farming beyond the floodplain. Image from Bein, Frederick L. (1978) “Land Use Patterns along the Nile.” Sudan Notes and Records. Vol. 58, pp. 180-189.

The construction of the Aswan Dam drastically changed this flood plain agriculture in Egypt since the rejuvenating silts no longer enrich the flood plain in Egypt. Diesel fuel pumps now irrigate the flood plain as well as larger farms in the desert. Chemicals are now applied to fertilize the land. However in Sudan, upstream from the dam, the high flood still occurs, depositing its silts on the flood plain.

Water is pumped up onto the flood plain to irrigate the crops. Ancient water lifting devices, the shaduf (water wheel) and the saquia (lever) were still in operation in Sudan in the 1970’s where diesel fuel pumps could not be afforded.

The floodplain cultivation produces a large amount of food for the Sudanese. Surpluses are sent to the towns and cities. The vegetables sent to the cities come mainly from the gerif.

A Tuti Island farmer harvests kale to send across the river to the Khartoum market. Photo by Rick Bein 1974.

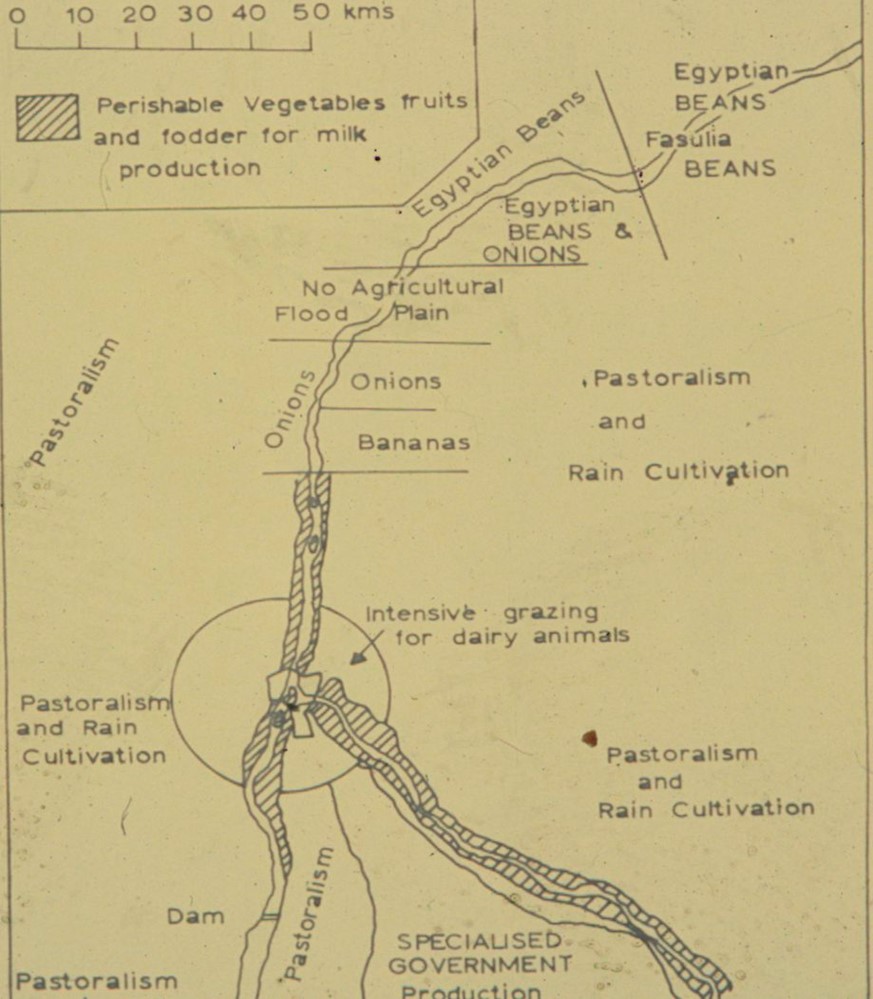

Specific crops tend to change with distance from the Khartoum market. Perishable vegetables are cultivated within a short distance from Khartoum. More durable fruits and vegetables are grown further away. See land use map below).

The Land-use map on the right depicts different crops growing along the river. Image by Bein, Frederick L., (1978) “Land Use Patterns Along the Nile.” Sudan Notes and Records. Vol. 58, pp. 180-189. Photo by Rick Bein 1976.

Wad el Basal, beyond the edge of the date trees that line the flood plain, a Faqui (holy man) pumps water into the desert where he runs a Koranic school where boys between 3 and 8 years learn how to raise onions. At 8 years of age most of the boys leave and start primary school. Two of my university students are pictured on the left.

The ancient arrangement provides each property with frontage on the Nile, where farmers cultivate the gerif and the irrigation floodplain. Ownership is inherited and divided among the heirs and the narrow piece of land is sliced even smaller. Title to the land can be held by hundreds of heirs, but one relative does the farming by agreement. Today, urbanization had offered much more opportunities where all the other heirs can occupy themselves.

Mechanized agriculture Flood plain Gerif

Three types of traditional long-lot farms line the Nile are defined by the notations under where they occur. Image photographed from commercial airline by Rick Bein 1976.

A diesel fuel pump takes water up beyond the floodplain to irrigated crops in the desert. Photo by Rick Bein 1976.

The Gezira scheme was started by the British early in 1925 to grow cotton for the English textile mills. A million acres were brought under irrigation from the Senar Dam on the Blue Nile. Water from the reservoir was distributed through a 2,700-mile network of canals to the farms between the Blue and White Niles. Following independence in 1952, farmers now grow many other crops and send some cotton to Sudanese textile mills. Other crops include oil-seeds, peanuts, wheat, sesame, sorghum, millet, and vegetables.

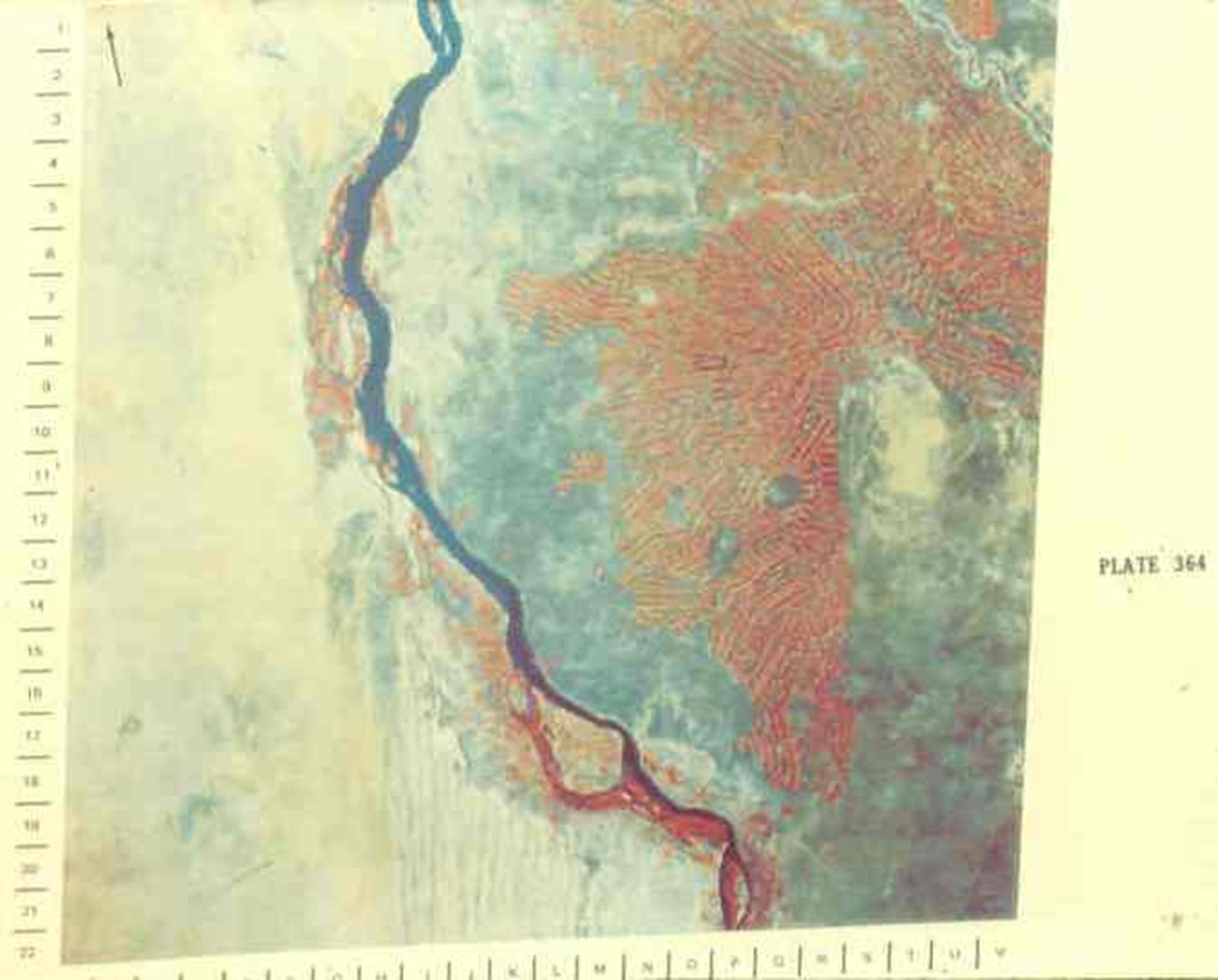

This Infrared image of part of the Gezira scheme shows the White Nile on the left and the Blue on the top right. The farmland is shown as red. Image from Landsat.

Sorghum is the crop most cultivated in Sudan and is dependent on rainfall. In the semi-arid Sahel away from the Nile successful crop years are not that frequent. Maybe two good years in a five year period provide enough grain to eat. When there is good rainfall year, more than adequate grain is produced. The extra grain is stored in pits (matmuro) on the periphery of villages where it will remain hidden until needed in a few years. About a quarter ton of grain is stored in each matmuro and covered with a layer of chaff from the previous harvest and a layer of clay soil is added on top. This grain remains edible for up to seven years. Each farmer knows exactly where his grain is hidden in this seemingly endless clay plain. This unique practice supports the village in good and bad years, remaining undisturbed by any marauding army or other tribes. If the villagers need to flee they know when they come back in a few years there will be sorghum waiting for them.

Matmuro grain storage preserves the grain for several years. The black clay swells when wet and seals the grain from any rainfall moisture. The chaff keeps the crumbs of the soil from mixing with the grain and can later be easily winnowed out. Photo by Rick Bein 1975.

This rain fed agriculture extends four hundred miles to the south where the Nuba Mountain people also maintain some unique farming traditions of the Sahel. On the flat land sorghum is grown in much the same manner. The only addition is the women have their agriculture apart from the men. The women farm the steep hillsides by using terraces (Jebraca) to reduce erosion.

The women farm the steep hillsides by using terraces (Jebraca) to reduce erosion but also to create more level places to plant sorghum. Photo by Rick Bein 1977.

Nuba grain storage structure for sorghum. Sorghum seed for the following year ,hangs on outside of the structure. Millet heads, Images by Rick Bein 1977

Traveling within Sudan provided a more extensive perspective of life throughout the country. My first visit was to Dongola, north of Khartoum along the Nile. An American colleague, Chris Winters, went with me. This trip took two phases. First, we took a convoy truck (lorries) at night across the desert to Merowe. Traveling at night was advantageous as the lorries spread out about a quarter of a mile apart to avoid each other’s dust. The lead lorry navigated with the stars, while the others followed the taillights of the lorry ahead. We arrived in Merowe at dawn and spent the day visiting ancient ruins and on the following day boarded a steamboat that took us down the river to Dongola.

https://joshuaproject.net/people_groups/11607

https://joshuaproject.net/people_groups/11607

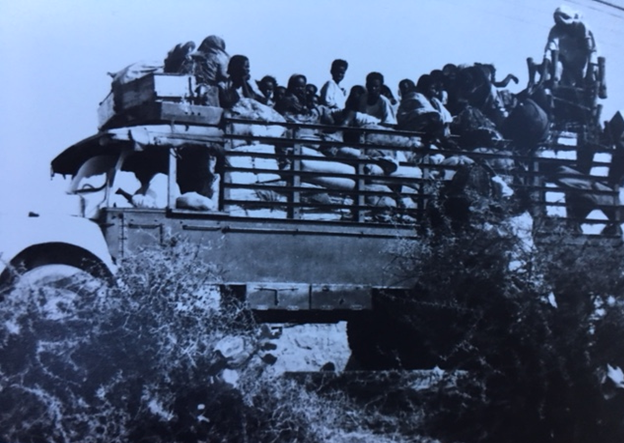

Passenger lorry by Rick Bein 1975. River boat by Creative Commons CC0 (CC0 1.0 Universal (CC0 1.0) Public Domain.

One embarrassing memory near the beginning of this journey occurred shortly after departing Khartoum. The Lorry left the city at four PM and drove until sundown where we stopped, and everyone descended. A blanket was spread on the ground where food donations were laid. This was the Ramadan breakfast which occurs when the sun sets after a long day of fasting. Muslims consume no food during the daylight hours for the month of Ramadan.

A wealth of food is brought out to share. Only the right hand is used when eating the meals. Picture by Rick Bein 1975.

Although we had no food to share, they invited us to share in their feast. The food was delicious, and everyone picked food up with their right hand. At one point I negligently reached for some food with my left hand, something that is never done in Islamic society. The people began leaving the circle, disgusted at what I had done, particularly at the sacred Ramadan breakfast. I was mortified. Later they forgave me for my mistake.

You may have noticed above that there are no women in the circle of desert diners. The women get to eat what the men picked through.

Another eating event occurred after we arrived in Dongola. At another evening breakfast in a small neighborhood a hors d’oeuvre was brought out while the main meal was being prepared. Marara, eaten traditionally in many parts of Sudan, consists of a plate full of raw sheep entrails. As the guest I was asked to serve myself first. I was aghast at this presentation, let alone eating any of it. I looked to ask my colleague, Chris, what to do in this situation, but he had suddenly disappeared. Being so new to the culture I was unsure what to do and did not want to offend anyone again. I decided that I had to be a good guest and eat. So, I chose a small piece and stuck in my mouth and began to chew. Even though being small, it was difficult to manage because it was like chewing on a small piece of rubber hose. Mixed with my saliva it began to swell and when I bit down hard, some liquid squirted out into the back of my mouth! To avoid retching I just gulped and swallowed it down. Having seen my accomplishment, they were delighted to offer me another piece! I declined since I had already done my duty.

Later, back in Khartoum, I related this story to some of my Sudanese friends who all gagged and said we never eat that stuff! No one would have been offended if you had refused.

Professor Mustafa Khogali was studying water resources along the Atbara River in the Butana Desert northeast of Khartoum and southeast of Meroe. He invited me to go with him. The Atbara River is a little-known tributary to the Nile that contributes about 10% of the water during the rainy season. During the dry season, the time of our visit, the river dries up leaving stagnant pools inside oxbows.

Water remains pooled in an oxbow of Atbara River during the dry season. This water is polluted with animal and human waste, and with shistosomes. Nomads are camped nearby while their children play in the polluted water. A shallow hole is dug about ten inches from the edge of the standing water allowing it to seep through, filtering out some of the contaminants to produce a more potable water. As the water evaporates another shallow hole is dug closer to the retreating water. Photos by Rick Bein 1974.

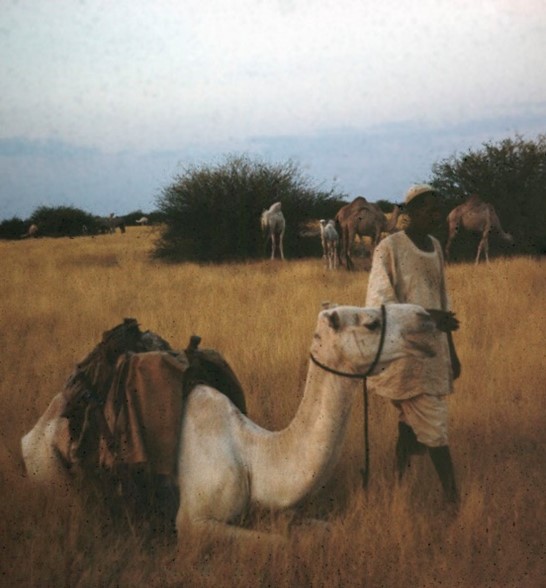

We continued our journey further out to where no ground water was available. We came upon a herd of camels harvesting the succulent berries from thorn bushes. Camels can get their water from these tiny fruits. No other grazing animals can survive here. When we stopped to take pictures, a nomad came running out of the bushes and asking if we had any water.

“Sure” we said and pulled out a jug of water and poured him a glassful. He drank that up in a hurry and after two more glassfuls he had his fill and thanked us. When I asked him

“When was your last drink of water?”

“Six weeks ago,”

I asked, “How do you survive so long without water?”

“Camel’s milk he replied.”

He showed us a little leather bag where kept some camel’s milk. I smelled it and it had a rancid odor but had to taste it. Its taste exceeded the odor, and I did not swallow it. Everything was fine for a while after that. But the next morning I was miserable and for two more days I still had to keep an eye open for restrooms.

Bedouin and his camels. Notice that the grass has not been grazed, meaning no cattle, sheep or goats can survive here for lack of water. The agile lips of the camels can reach between the thorns and pluck the tiny fruits that sate the camels’ thirst. The camels are being fattened to be sold as meat in Egypt and Port Sudan. The nomad stands beside his herd camel that he rides to drive the others around. She also shares her milk with him. Photos by Rick Bein 1974.

After a year in Sudan, my Arabic was adequate to travel by myself. One trip I took was to Darfur Province in western Sudan. I took one of the transport lorries to the town of El Obeid, Kordofan province and transferred to another lorry to Genena close to the Chad border. We stopped to let people off at villages and I descended to take some photos.

Thorn bushes are collected and used as fences to keep out domestic animals and pests. Photo by Rick Bein

Children guard harvested sorghum from birds. Photos by Rick Bein 1975,

When we left, the village dogs came barking after us for several miles. Every village had a pack of dogs that would emerge and chase any vehicle that passed. I was impressed with the speed and endurance of these dogs. I believe they could compete well with racing gray hounds. It seems that the dogs do not belong to any one villager, but everyone gives them food scraps. Children play with them, but their main function is to contain the village rats.

Darfur (home of the Fur) was an independent sultanate for several hundred years and was incorporated into Sudan by Anglo-Egyptian forces in 1916. Being 600 miles from Khartoum and the culture of the Nile, the Fur have very little affinity for the rest of Sudan. Not being Arabs they have operated somewhat independently but in recent years when they tried to take their independence and the Omer Bashir’s military forces viciously squashed the attempt. A semi-vigilante Arab group called the Janjaweed, sponsored by Khartoum government continues to pillage and destroy villages and disrupt their water supplies. Because of this war between Sudanese government forces, Darfur has been in a state of humanitarian emergency since 2003. The Fur have been experiencing a genocide and most have fled to neighboring Chad.

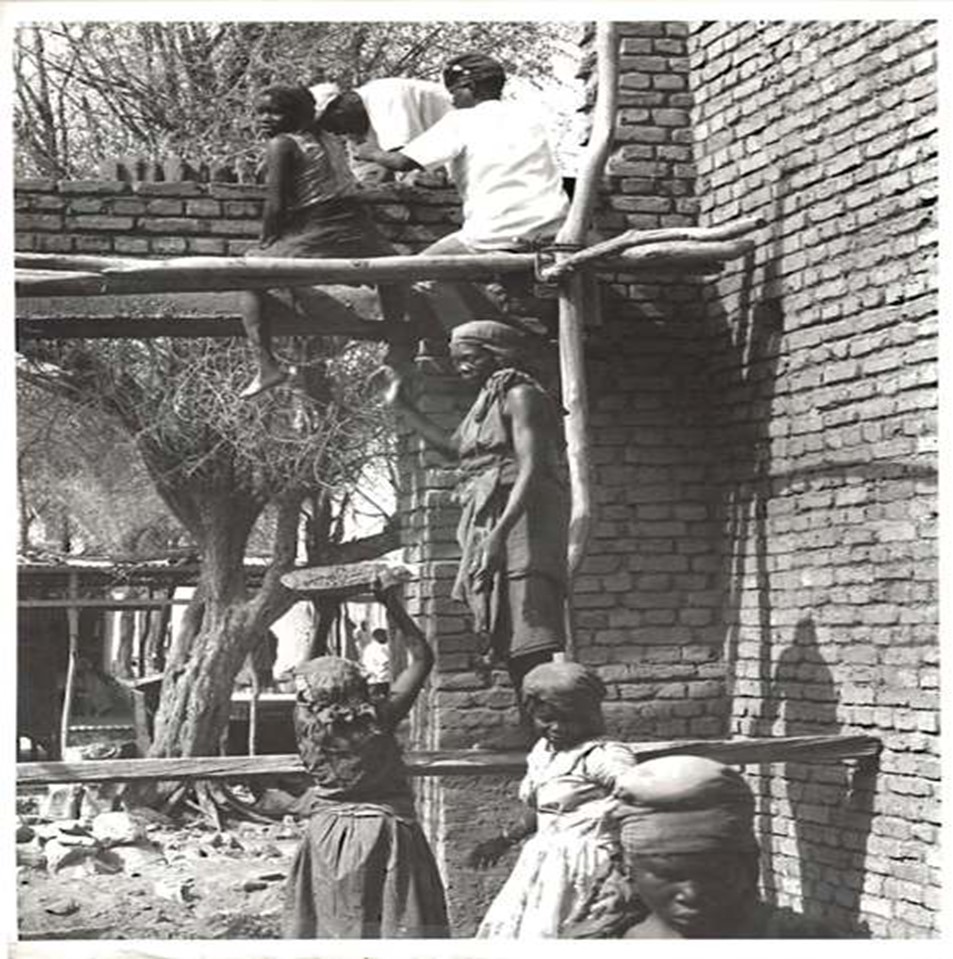

Polygamous family building a house in Genena, Darfur. The Koran allows a man to have four wives, an arrangement which brings security for the women and wealth for the man. Photo by Rick Bein 1975.

Polygamous family building a house in Genena, Darfur. The Koran allows a man to have four wives, an arrangement which brings security for the women and wealth for the man. Photo by Rick Bein 1975.

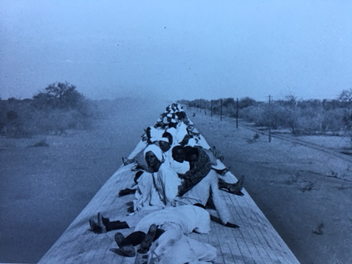

Men ride on top of the train for free while they buy tickets for their wives and children to ride inside. Photo by Rick Bein 1975.

My visit there in 1976 was met by peace and tranquilly and I spent some days meeting people taking little tours to nearby villages. As I was walking around Genena, I saw a Fur family building a house and from a shop across the street I was able to photograph their activity. What I saw was the man and his son up on some homemade scaffolding building a wall with bricks. He had four wives helping down below. One was mixing hod while another carried it to a third wife who relayed it up a ladder to the brick layers above. Meanwhile the fourth wife showed with a large tray of food for the midday meal.

Another occurrence was meeting Assam a young man who had earned his bachelor,s degree from the Geography Department at the University of Khartoum. He had been working in a government office for a few years. As we talked, he expressed his interest in returning to the University to pursue a master’s degree. I encouraged him to do so and I carried copies of some of his documents with me back to Khartoum. A month later he showed up on campus and within a year he had finished his master’s degree and headed out of the country to complete a PhD. The last I heard he was a professor of Geography at King Saud University in Saudi Arabia.

While still in Genena, Assam told me of a more comfortable alternative way to return to Khartoum. There was a train that ran from a neighboring Nyala, a town about 60 miles away, on to Khartoum. I decided that would be another adventure and when I left Genena, I took a lorry to Nyala where I bought a ticket on the train. That was an interesting journey. I noticed that there were only women and children in my train car. Once we pulled out of the station, a crowd of men (probably the husbands) came running up to the train and climbed the ladders to the roof. Fortunately, the train could only travel at 15 miles per hour because of the poor condition of the rails. It was not too dangerous for a free ride! At the consternation of the porter in my car I decided climb up there also, but just long enough to take this picture.

I had heard about the Nuba Mountain People, a group of tribes unique to themselves living in the province of Southern Kordofan about 400 miles southwest of Khartoum. I decided to go visit the Nuba in 1975 and took a passenger lorry to Kadugli the provincial capital. In Kadugli I began looking for a vehicle going to the Nuba Mountains. I ran across a young couple who had visited the village of Buhram a few months prior. They had driven their camper to the small community and were impressed with their visit. They suggested that I go there since I had no other plan. I began asking around the market for a lorry going there. I immediately found one leaving first thing in the morning.

- The mountains cover an area roughly 64 km wide by 145 km long (40 by 90 miles), and are 450 to 900 meters (1,500 to 3,000 feet) higher in elevation than the surrounding plain.

- The mountains stretch for some 48,000 square kilometers (19,000 square miles).

- The climate is semi-arid with under 800 mm of rain per year on average, but lush and green compared with most nearby areas.

- There are almost no roads in the Nuba Mountains; most villages there are connected by ancient paths that cannot be reached by motor vehicles.

- The rainy season extends from mid-May to mid-October, and annual rainfall ranges from 400 to 800 millimeters (16.4 to 32.8 in), allowing grazing and seasonal rain-fed agriculture.

- Population is approximately 1.7 million in 2019

Statistical summary of Nuba Mountain Mountain Mountains Encyclopedia Britannica 2010.

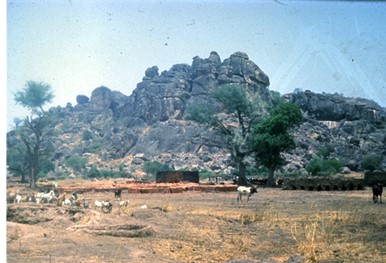

The lorry was carrying household goods and six passengers including me. As we approached a craggy outcrop emerged on the horizon and we proceeded directly toward it. At its base was an Arab settlement of about 4 small shops the homes for about 10 families who greeted me warmly and wanted to know why I was there. I told them that I came to see the Nuba. They told me to go around the base of hill until you see them. The Arabs told me that when I was finished, I should return to them because they had a place for me to sleep and I would join in a feast that they were preparing. Not knowing what was ahead, I accepted their hospitality.

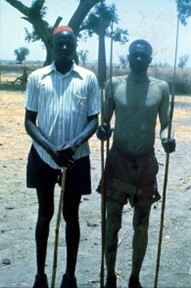

Approaching Buhram community showing local Arab brick works, and cattle nomads. The lead Nuba farmer is wearing my extra shirt, skull cap boots and shorts. Also included is the local metal worker showing his spears made from scraps left from Rommel’s WW2 tanks. Rick Bein 1977.

I grabbed my backpack and after 300 yards I came upon a few Nuba people we were happily curious about me. A few of them spoke a few words in Arabic and I told them I wanted to see their agriculture. They took me over to sit with them around a tree. The dressed only in shorts, men and women alike. Everyone was barefoot and wore nothing on their heads. They were all large people, no one under 5’10”. Several of the Nuba came to look at this strange white man; they seemed as curious about me as I was about them. Some women bought some sorghum mash to eat and some water. I really was hungry and thirsty. I knew that the water might not settle well with me, but I wasn’t going to run back to the Arab settlement just for a drink.

Meanwhile, they brought someone they all recognized as being one of their better farmers. They wanted to address my mission to visit their farming areas. He decided to match his dress as closely as could to mine. He had a skull cap and wore probably the only pair of boots in the community. He seemed somewhat uncomfortable in the boots. We started out, neither of us able to communicate verbally. He pointed out their main crops, sorghum, and millet which I was familiar with. Then we came to a field of 3-foot stalks standing about 2 feet apart. What are these? He said “gooton” which was the Arabic for cotton. The stalks caught me off guard since in the States cotton farmers get rid of the stalks since they might carry diseases that would affect next year’s crop.

Cotton Stalks left behind after harvest.

Nuba woman passing up drinking water colored by Kaolin. Photos by Rick Bein 1977.

This was a puzzle to me. They did not have any capability to process cotton. “Why cotton?” “Groosh” was his reply. Arabic for money. What do you do with Groosh? He showed me a plug of chewing tobacco from his pocket.

Then the relationship between the Arabs and the Nuba became clear. The Arabs played to the Nuba addiction to chewing tobacco which they supported by trading their cotton. When we got back to the tree, I took notice that the whole community was hooked on chewing tobacco. These Arabs being Muslim also had a mission to recruit the Nuba to Islam. A few Nuba had converted.

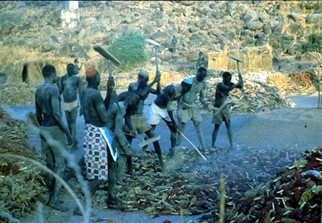

Instead of going back to the Arab settlement, I became fascinated by the sorghum grain threshing that was happening.

Nuba Women going out to the underground granaries to bring sorghum heads back to the village to be threshed. On the right, men and women cover their bodies with sacred flour and beat the grain heads with threshing boards. In the bottom right corner sorghum heads are ready to be threshed.

Sorghum heads waiting to be threshed in the for-ground, and immediately above the already threshed grain that will be stored in a matmuro. Woman winnows some grain before being ground into flour. Photos by Rick Bein 1977.

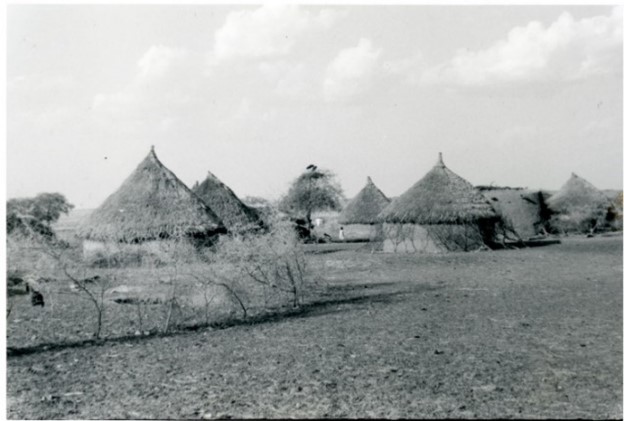

While I was taking pictures of all the happenings, the village architect came and said “come with me to see the houses”. He was very proud of his artistic ability and wanted to show off the homesteads that he had completed. Each family lives in a small compound made of a circle of five round structures. Small mud walls connect each of the small buildings to create a closed circle. Each small building has a different purpose. The most important is the granary, holding the food supply. It is decorated with elaborate designs to keep away evil spirits. The keyhole shaped door provides the entry way which is also the master bedroom. There is a separate room for cooking and food preparation. The other two rooms are for the children. This housing arrangement still continues today and can be seen from expanded “Google Earth” views.

The master Architect shows off the household granary. His home sits on the hill to provide a lookout for enemies and to see arriving supply trucks. Photos by Rick Bein 1977.

Among the many other cultural attributes, I choose to focus on two items of interest. The Nuba are known for their Martial Art of wrestling. Children learn to wrestle in their play time. This continues and becomes a rite of passage when reaching adulthood. Women as well as men are excellent wrestlers. On certain evenings just before sundown teenagers compete in wrestling matches. Adults maintain their skills should they need to protect themselves from invaders. The wrestling matches consist of the combatants posturing (more pronounced for the girls) trying to intimidate their opponent, but the actual contact is extremely quick, usually thirty seconds. The winner merely must throw the other on the ground.

I spent a bit of time with the village champion who half in jest challenged me to a bout. Although we were the same size, I decided I would not stand a chance and declined. Anyway, we both had a good laugh. In a prior time, the Nuba and their martial arts were recruited to serve in the Sudanese army. Ironically with the reign of Omar Bashir (1985-2019, the Nuba suffered series Genocidal attacks and were forced to live hidden in caves.

The baobab tree bark serves as a source of cloth. It is beaten until soft, and the sheets are fashioned into shorts and tops. This tradition had diminished greatly when I was there because western style clothes came free from the developed countries. Unfortunately, Goodwill does not provide feminine products and the women used the baobab fiber.

The entire community, Arabs and nomads come to watch the excitement. The baobab tree bark serves as a source of cloth. It is beaten until soft, and the sheets can be fashioned into clothing. Photos by Rick Bein 1977.

The Nuba community seemed enamored by my willingness to participate in whatever they were doing, that they forgot that I came to see their agriculture and included me in all of their traditional activities. Things seemed to flow so well that I forgot that I had promised the Arab shopkeepers that I would be back to enjoy their hospitality. As night progressed, the Nuba told me that I could sleep on a cot outside one of their homes. Even though it would have been much more comfortable to stay with the shopkeepers, I was caught up with the experience at hand and decided to stay with the Nuba. It seemed too awkward to run back to the settlement and refuse their offer.

After three days, I realized that I needed to get back to Khartoum, at which time I returned to the settlement to apologize to the shopkeepers and wait for the next lorry going to Kadugli.

Back in Khartoum my stay there was winding down before we were to leave. Mary and I wanted another child, but the doctors in the States said it would need to be by cesarean birth since the twins had been born cesarean. Once a cesarean, a cesarean was always the rule. However, we heard that was not necessarily true and depended on the circumstances during the birthing process. After consulting an obstetrician in Khartoum, we were told that he would be alright with a normal delivery if the baby was born there. So, we proceeded. Leila was delivered normally in May, two months before we were to return to the States.

My memories of Sudan are all favorable. We were blessed to have been there at a time of peace. Although there were a few governmental disturbances, the general population was hardly impacted. Under the recently deposed dictator, Omar Bashir (2019), Sudan experienced severe violence and genocide, and now hopes to proceed toward democracy, which now has failed again. Without dictatorial rule, different factions begin expressing their agendas that frequently promote civil war. This sometimes results in separation into separate countries. From the time of colonial emancipation, until the time I was living there, this separation had not happened anywhere in Africa. Since then, Eritrea has become its own country. Independent South Sudan has its trials. Darfur in the far west would like to have its own country, the Nuba would like to break away and possibly join South Sudan. It saddens me to see a country that filled me with such excellent experiences succumb to violence and tragedy.