80 Farming in Iceland

Rick Bein

Farming in Iceland

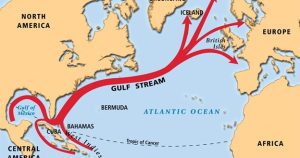

Iceland is not commonly thought of as a place where farming can prosper. Because of its far north latitude, just below the Artic circle, one would expect a climate far too cold for agriculture. However, because of the Gulf Stream Current bringing warm water from the region of the Gulf of Mexico, Iceland is warmed enough that vegetation can prosper.

The Gulf Stream is made of water warm in the Gulf of Mexico that flows North through the Atlantic Ocean.

The Gulf Stream is made of water warm in the Gulf of Mexico that flows North through the Atlantic Ocean.

Surprisingly, only one percent of the Island is used for agriculture, but it significantly contributes to the economy. Agriculture ranks third after tourism and fishing to make up the national income. The southern part of the island entertains most of the geothermal tourism and contains the largest number of farms. The north has extensive areas of green acres supporting crop and livestock farming.

Physical map of Iceland. About 78% of Iceland is agriculturally unproductive. Green areas along the periphery of the island are where agriculture is possible.

Raising sheep (the traditional mainstay for generations of Icelandic farmers, and cattle make up the majority of livestock while pigs and poultry are also raised. Iceland is self-sufficient in the production of meat, dairy products, and eggs. There are over 700 dairy farms in Iceland.

A variety of hearty food crops, such as potatoes, turnips, carrots, cabbage, kale, and cauliflower are grown. In the more populated south, other subtropical crops such as tomatoes, cucumbers, green peppers, flowers, and potted plants are grown in greenhouses heated with geothermal energy. In some cases, artificial light is used to account for the shorter winter daylight hours.

Grass, a perennial crop occupies over 90 percent of the agricultural land, is the main fodder crop which grows well in the long periods of daylight in the short, cool summers. Being a perennial crop, it can start growing again as the weather warms. Rye and barley are also grown. Ninety nine percent of agricultural land is dedicated to growing fodder. The cool climate provides certain advantages for agriculture as the lack of insect pests means that the use of agro-chemical like insecticides and herbicides is low. There is a general lack of pollution from the sparse population which means that food is less contaminated with artificial chemicals

Farm in Klofningsevegur, in northwest Ireland. Photo by Rick Bein July 11,2022

Traveling in the northwest of the island, I found a predominance of hay and sheep. I was constantly aware of sheep roaming freely, crossing the road with abandon. There were signs alerting the drivers of this hazard. Someone told me to be more careful after one sheep crosses, because she might soon be followed by her lamb(s). Fortunately, I had no such collision.

When asking farmers what crops they grow, I was expecting some variety, but the answer was “hay”. “That’s all?” “Our hay is grown to feed our sheep.” “Any other animals?’ I asked. “A few horses for rounding up the sheep when summer ends.”

Islandic horses (from Holmavik) and sheep came with the first settlers 1000 years ago and have become unique breeds as Islanders prevent any genetic mixing by preventing importation of different breeds. Photos by Rick Bein and Ellis Pawson, July 2022.

When asked why sheep are not confined in corrals, they answer “Only in the winter do we keep them in our pastures. In the summer we release them to graze the wild grasses that grow on the land which is too hilly for farming. The more level lands are needed for growing hay to feed the sheep during the winter. Hay is stored in those big plastic covered bales for that purpose”.

After mowing the hay, it is stored in heavy plastic that keeps the hay preserved and free from mold and any additional moisture. This is a technique used around the world. Photo by Rick Bein July 10, 2022, Fljostshlioarvegur, Iceland.

Over the summer ewes and their newly born lambs wander freely and are scattered throughout the hills. As temperatures become cold, communities organize round ups using their horses to bring in the sheep. All the sheep are driven into a sorting corral (rittir) where each owner claims his sheep based on his cut marks in the ears of the ewes. The lambs stay close to their mothers and are collected at the same time. As the lambs have grown to market size, they are sent to the packing plant.

Rittir where sheep are sorted after bringing them out of the high ground during the Fall round-up. Photo taken in Fljotshlioarvegur by Rick Bein June 2022.

Rittir where sheep are sorted after bringing them out of the high ground during the Fall round-up. Photo taken in Fljotshlioarvegur by Rick Bein June 2022.

The ewes are then moved into the hay fields where the large bales of hay remain. These are opened one at a time as the sheep consume them over the winter. Rams begin breeding the ewes and the cycle starts over again.

Hardy vegetables are grown in small plots near the households throughout the island. These root vegetables include potatoes, beets, carrots, and rutabagas, growing underground are less affected by the cold weather can be harvested later. Other cold weather vegetables such as cabbage and rhubarb are grown outside, but do better in green houses.

This Farmer keeps a greenhouse to enhance his family and neighbors’ diets. Klofningsvegur 371 photo by Rick Bein July 10. 2022.

This Farmer keeps a greenhouse to enhance his family and neighbors’ diets. Klofningsvegur 371 photo by Rick Bein July 10. 2022.

Greenhouses supply most of the fresh vegetable to Reykjavik and other urban centers in the south, Tomatoes are grown in this high-tech green house where they are tied vertically to twelve-foot cords attached to the ceiling. Photo taken in Lynbrau, Reykholt by Rick Bein July 2022.

Greenhouses supply most of the fresh vegetable to Reykjavik and other urban centers in the south, Tomatoes are grown in this high-tech green house where they are tied vertically to twelve-foot cords attached to the ceiling. Photo taken in Lynbrau, Reykholt by Rick Bein July 2022.

There are some challenges to Icelandic agriculture, such as the threat of invasive species from outside the country. Alaskan Lupin is an example that seems to be taking over un-vegetated land and invading farms. Some think it helps control soil erosion. Most feel that the jury is still out about this plant and do not like it.

Icelanders have been careful to preserve the purity of their sheep and horse breeds by forbidding the importation of any foreign breeds.

This manicured farm in the background is facing the spread of the Alaskan Lupin in the foreground. Photo by Rick Bein July 3, 2022. Location 1,871, Iceland.

This manicured farm in the background is facing the spread of the Alaskan Lupin in the foreground. Photo by Rick Bein July 3, 2022. Location 1,871, Iceland.

References

Data was collected during the June-July 2022 National Council for Geographic summer teacher field course to Iceland.

Google Earth, https://www.google.co.jp/intl/ja/earth

Farms of Iceland: Names, Facts, and Features – Iceland.org Erpsstadir Farm

www.iceland.org/geography/farm

Encyclopedia Britannica https://www.britannica.com/place/Atlantic-Ocean

Encyclopedia of the Nations “Iceland – Agriculture” www.iceland.org/geography/farm

Iceland Review – Iceland Review https://www.icelandreview.com

Iceland Weather, Climate, & Temperature Year-Round https://guidetoiceland.is/travel-info/climate. Author: Nanna Gunnarsdóttir