23 Perspectives on the Amazon Rain Forest

I visited the Amazon basin three times so far. The most memorable time was the first time in 1966 when I took my one-month Peace Corps vacation and traveled solo from Mato Grosso over to the cities of Porto Velho, Rio Branco de Acre, Manaus, and Belem do Pará. Part of the trip, I spent glued to the airplane windows snapping photos. The stops were major learning experiences.

Route of my tour 1966. Mapa do Brasil by thejourney1972 (South America addicted) license under CC BY 2.0 1975

Route of my tour 1966. Mapa do Brasil by thejourney1972 (South America addicted) license under CC BY 2.0 1975

Porto Velho was a rubber collecting depot located at the base of the rapids (Cachoeira de Teotonio) on the Rio Madeira. Rubber harvested from the upper reaches of Rhondonia and eastern Bolivia was brought by barge to the top of the rapids, where it was downloaded onto the Madeira-Mamore Railroad to bypass the 40-kilometer rough stretch of the River. Porto Velho, at the base of the rapids, was a break-bulk point for transportation and the natural place to locate the State Capitol of Rondônia.

In 1966, Porto Velho was a rough town, with dirt streets, several bars and and men with pistols on their hips. The busiest part of town was where the train unloaded large balls of rubber to be transferred onto barges that continued the journey downriver to Belem near the mouth of the Amazon River.

It was in Porto Velho where I met the eccentric, entrepreneurial old Texan. That encounter is described in another chapter.

As a major rubber-producing center in 1900, Porto Velho in 1966 had been reduced to a provincial outpost where other forest products, including small amounts of rubber, were sold. That rubber was produced at the household level, where forest families collected latex from a couple of rubber trees. Once a month, they would bring one or two 40-pound rubber balls to the nearest trading post to exchange for household items.

Rubber tapping involves cutting angled slits in the bark of a rubber tree (Hevea brasiliensis) so that the sap would slowly ooze into a collection bucket.

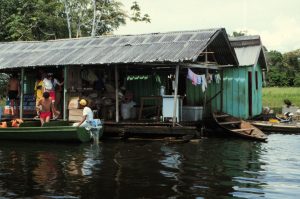

Floating trading post by Rick Bein, 1966.

Old Rubber tree (Hevea brasiliensis) located at the Amazon Museum. This tree has survived many tappings. Each slit represents one tapping. Photo by Rick Bein, 1966,

After a few days, the bucket is emptied into a large pot. When there is enough sap, it is boiled slowly until a sticky mass of latex remains. From there, the latex is rolled onto a two-inch diameter wooden pole, where it cools into a ball. More latex is added until it reaches a manageable two-foot-wide by three-foot-long ball. Then the forty-pound rubber ball is carried out of the forest on the pole to where it will be sold at a trading post.

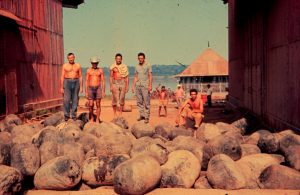

These balls of rubber were produced at the household level in the State of Rondonia and eastern Bolivia and brought to a floating trading post along the river, where they were exchanged for salt and kitchen items. The rubber was collected by small businessmen who shipped it downstream to resell it to larger companies. This rubber was offloaded above the Teotonio Rapids and brought by train to Porto Velho, Rondonia, where it was reloaded onto a barge to continue the trip to Belem near the mouth of the Amazon River. The workers posed on top of these rubber balls long enough for me to take this picture in 1966.

These balls of rubber were produced at the household level in the State of Rondonia and eastern Bolivia and brought to a floating trading post along the river, where they were exchanged for salt and kitchen items. The rubber was collected by small businessmen who shipped it downstream to resell it to larger companies. This rubber was offloaded above the Teotonio Rapids and brought by train to Porto Velho, Rondonia, where it was reloaded onto a barge to continue the trip to Belem near the mouth of the Amazon River. The workers posed on top of these rubber balls long enough for me to take this picture in 1966.

This artisan rubber collection differs greatly from the mass production that occurred around 1900. At that time, large-scale rubber collection dominated the whole region. This rubber boom was stimulated by the demand for automobile tires. Ecologically, this boom self-destructed when the natural predators of the rubber grew along with the expanded production, creating an expensive and weakening rubber crop. Henry Ford’s “Fordlandia” rubber plantation failed miserably. The crowning blow to the industry was the successful cultivation of rubber trees in other tropical regions where there were no natural predators. Almost overnight, the booming multi-million dollar industry collapsed in 1904.

When I traveled on to Manaus, I could see the remains of the once vast rubber landscape. Manaus was once the center of world rubber production, a booming town flowing with activity. The Manaus Opera House hosted Broadway productions that traveled by passenger ship from New York and up the Amazon River to Manaus. When I toured the Opera House in 1966, it was in major disrepair, rafters were falling from the ceiling, windows were broken, artifacts were stolen, and vandalized. Cobwebs dominated the aisles, and dust lay everywhere. I wondered if it was due for demolition.

Amazon Theater, Inaugurated in 1896. Photo owned by Histórico Nacional pelo IPHAN from 1966. Photo by Rafael Zart, creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 September 20, 2019

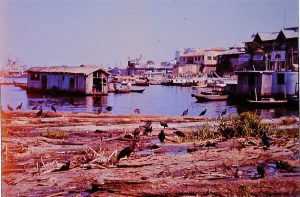

I was intrigued with the floating city (Cidade Flotuante), a massive slum extending from the port out into the River, moored only by ropes and connected by planks leading from floating structure to structure. Shanty homes housed large families next to little shops. Each building was tied to another one closer to the land. Fortunately, the annual flood of the Amazon River did not have a major effect on the community because Manaus is located on the Rio Negro branch of the river, which has less of an increase in flow. However, the flood of the main Amazon extends up the Rio Negro, but causes minor turbulence, so the Cidade Flotuante merely rises up and down each year. The seasonal difference in water level is about 10 meters. The main shipping port has a major ramp that hinges up and down in different seasons to accommodate vehicles moving on and off ocean-going ships.

Cidade Flutuante (Floating) occupied part of the harbor at the Port of Manaus. Shanties tied to logs provided homes for impoverished squatters. Photo by Rick Bein, 1966.

Encontro das Aguas, where the Rio Negro mixes with the Rio Solimões to form the main Amazon. The dark, organic-rich Rio Negro water is gradually integrated with the highly sedimented Rio Solimões. Photo by Rick Bein, 1993.

The magnitude of the Amazon River exceeds all other rivers, both in length (4,388 miles, debatable with the Nile River) and in water volume. At Manaus, where the two branches come together, it is estimated to be ten miles across during the flood season. Moving at 6 miles per hour, the river flushes everything it can reach. Changing course each year, ripping out new channels and carrying floating islands of vegetation. At the Atlantic Ocean, the gush of the brown sediment-filled water extends one hundred miles. Historically, Spanish sailors restored their ship’s drinking water supplies completely out of sight of the land.

Satellite view of the mouth of the Amazon shows the silt extending out into the Atlantic Ocean. Google Earth.

Satellite view of the mouth of the Amazon shows the silt extending out into the Atlantic Ocean. Google Earth.

Deforestation of the Amazon basin poses a major threat to the world. This vast ancient forest produces a major part of the Earth’s oxygen through the natural photosynthetic process. Also, the immense biodiversity that exists has hardly been explored, and who knows what benefits can come from future discoveries. The significance of these planetary benefits is hardly recognized by the Brazilian Government, which realizes very little monetary benefit from this massive 2.5 million square miles of real estate and wants to convert it to lucrative agriculture.

It is my opinion that the rest of the world should agree with Brazil, not to deforest, but to receive compensation for the loss of this hypothetical revenue. The rest of the world’s countries could contribute billions of dollars to this cause.

The process of clearing the rainforest starts as a form of slash-and-burn agriculture (also called shifting cultivation), where small farmers cut and burn the forest and then plant crops in the fertile ashes. Traditionally, the forest would be allowed to regrow for up to ten years before clearing again.

After three years, the ashes disperse, the soil wears out, and pests become a problem. Then the farmer abandons the farm and allows the forest to reclaim the area. He moves on to clear another piece of land. Photo by Rick Bein, 1972.

A major pest is the leaf cutter ant (formiga sauva), which normally finds natural clearings in the forest and struggles to keep the clearing open by cutting leaves to feed to their underground larva. Eventually, the forest wins out, and the ants seek another tree fall area to colonize. But when a farm clearing appears, the ants invade and devour the crops. Photo by Rick Bein, 1972.

While flying over the forest in a commercial airline in 1966, I snapped this photo. Several stages of the shifting cultivation are evident. The dark burned area is being prepared for planting. The land, center left and top right, has been recently abandoned. The pristine forest is located in the bottom right. In the top right is a second-growth forest that has been abandoned for years. It takes 200 years for the second-growth forest to attain the biodiversity of the pristine forest.

Cattle ranchers intercede in the shifting cultivation by planting invasive African grasses on the abandoned farmland. Since the African grasses have no natural predators, they outcompete the native grasses. Vigorous African grasses (jaragua, colonial, and pangola) have taken over. Also, periodic burning kills any new tree growth while encouraging the germination of the grass seeds. Vast areas are being taken over and permanently converted to pasture with no hope of any forest returning. More recent practice eliminates the farm cycle and plant the grasses immediately after the burn. An expansive charcoal business aids in the dispersal of any partially burned wood.

Tropical cattle from India survive quite well in the tropics of South America, and the spreading African grasses feed them well. Blowing the “berrante” signals the cattle that salt is available (white bag behind saddle). Photos by Rick Bein, 1971.

Tropical cattle from India survive quite well in the tropics of South America, and the spreading African grasses feed them well. Blowing the “berrante” signals the cattle that salt is available (white bag behind saddle). Photos by Rick Bein, 1971.

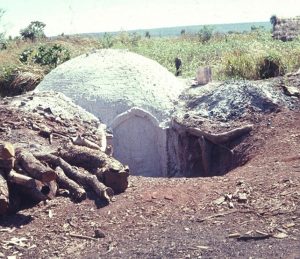

Charcoal production is another practice that encourages forest clearing, as the remaining wood is charred in kilns such as this. Photo by Rick Bein, 1971.

Charcoal production is another practice that encourages forest clearing, as the remaining wood is charred in kilns such as this. Photo by Rick Bein, 1971.

Mining for precious metals found in the alluvial sand and gravel deposits along waterways is also destructive to the environment, as toxins pollute the land and water, leaving large areas of wasteland.

Mining for precious metals found in the alluvial sand and gravel deposits along waterways is also destructive to the environment, as toxins pollute the land and water, leaving large areas of wasteland.

Garimpeiros are using sieves to separate diamonds from the river gravel. Mining is destructive to river banks and pollutes the water. Small-scale mining occurs throughout the Amazon basin. Photos by Rick Bein, 1965.

Garimpeiros are using sieves to separate diamonds from the river gravel. Mining is destructive to river banks and pollutes the water. Small-scale mining occurs throughout the Amazon basin. Photos by Rick Bein, 1965.

Once a road is created, the rainforest is now open for anyone to begin clearing. Small farmers can easily settle and begin their clearings, and as the population builds up, shops now appear to provide other services. Major lumbering can efficiently harvest massive hardwood into logs to be trucked away. A trans-Amazon road is in the planning by the current Brazilian government, which will sign the death null for a huge span of pristine rainforest. This has become very controversial at this time in 2022.

Roads open the environment to deforestation and development. Once established, there is no stopping the deforestation. Photo by Rick Bein, 1966.

Roads open the environment to deforestation and development. Once established, there is no stopping the deforestation. Photo by Rick Bein, 1966.

Another scenario would be to develop tourism as another source of income. Brazil considers this a benefit that could coexist with deforestation. Whatever the case, tourism has taken off.

When I returned to Manaus in 1986 and 2003, major changes had taken place. The Manaus Theater was being restored and was beautifully decorated. There was no evidence of cobwebs on the inside. Murals were being redone, and with its history, the building is considered a museum. This has become a major tourist stop.

Now, the Cidade Flutuante was gone, for me a fascinating cultural attraction, but it was seen as an ugly favela that would be viewed unfavorably by tourists. The squatters had been forced to find unwanted scraps of land to build their shanties, like on the edge of ravines leading to the rivers.