83 Interaction of respiratory and urinary systems

Learning Objectives

After reading this section you should be able to-

-

Explain the relationship between changes in alveolar ventilation (i.e., hypoventilation and hyperventilation), arterial blood PCO2, arterial blood pH, and arterial blood HCO3–

-

Define acidosis and alkalosis

-

Compare and contrast metabolic and respiratory causes of pH imbalances.

-

Describe the concept of compensation in relation to disruption of pH homeostasis.

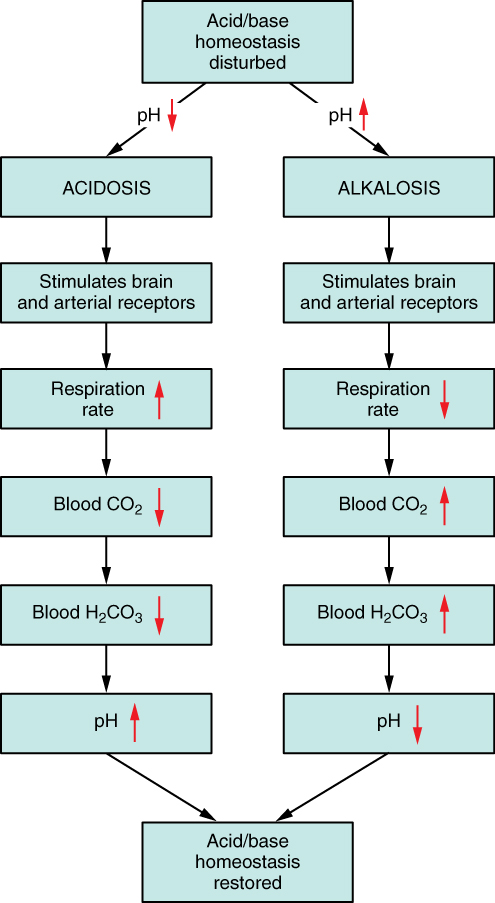

Respiratory Regulation of Acid-Base Balance

The chemical reactions that regulate the levels of CO2 and carbonic acid occur in the lungs when blood travels through the lung’s pulmonary capillaries. Minor adjustments in breathing are usually sufficient to adjust the pH of the blood by changing how much CO2 is exhaled. In fact, doubling the respiratory rate for less than 1 minute, removing “extra” CO2, would increase the blood pH by 0.2. This situation is common if you are exercising strenuously over a period of time. To keep up the necessary energy production, you would produce excess CO2. In order to balance the increased acid production, the respiration rate goes up to remove the CO2. This helps to keep you from developing acidosis.

The body regulates the respiratory rate by the use of chemoreceptors, which primarily use CO2 as a signal. Peripheral blood sensors are found in the walls of the aorta and carotid arteries. These sensors signal the brain to provide immediate adjustments to the respiratory rate if CO2 levels rise or fall. Yet other sensors are found in the brain itself. Changes in the pH of CSF affect the respiratory center in the medulla oblongata, which can directly modulate breathing rate to bring the pH back into the normal range.

Hypercapnia, or abnormally elevated blood levels of CO2, occurs in any situation that impairs respiratory functions, including pneumonia and congestive heart failure. Reduced breathing (hypoventilation) due to drugs such as morphine, barbiturates, or ethanol (or even just holding one’s breath) can also result in hypercapnia. Hypocapnia, or abnormally low blood levels of CO2, occurs with any cause of hyperventilation that drives off the CO2, such as salicylate toxicity, elevated room temperatures, fever, or hysteria.

Renal Regulation of Acid-Base Balance

The renal regulation of the body’s acid-base balance addresses the metabolic component of the buffering system. Whereas the respiratory system (together with breathing centers in the brain) controls the blood levels of carbonic acid by controlling the exhalation of CO2, the renal system controls the blood levels of bicarbonate. A decrease of blood bicarbonate can result from the inhibition of carbonic anhydrase by certain diuretics or from excessive bicarbonate loss due to diarrhea. Blood bicarbonate levels are also typically lower in people who have Addison’s disease (chronic adrenal insufficiency), in which aldosterone levels are reduced, and in people who have renal damage, such as chronic nephritis. Finally, low bicarbonate blood levels can result from elevated levels of ketones (common in unmanaged diabetes mellitus), which bind to bicarbonate in the filtrate and prevent its conservation.

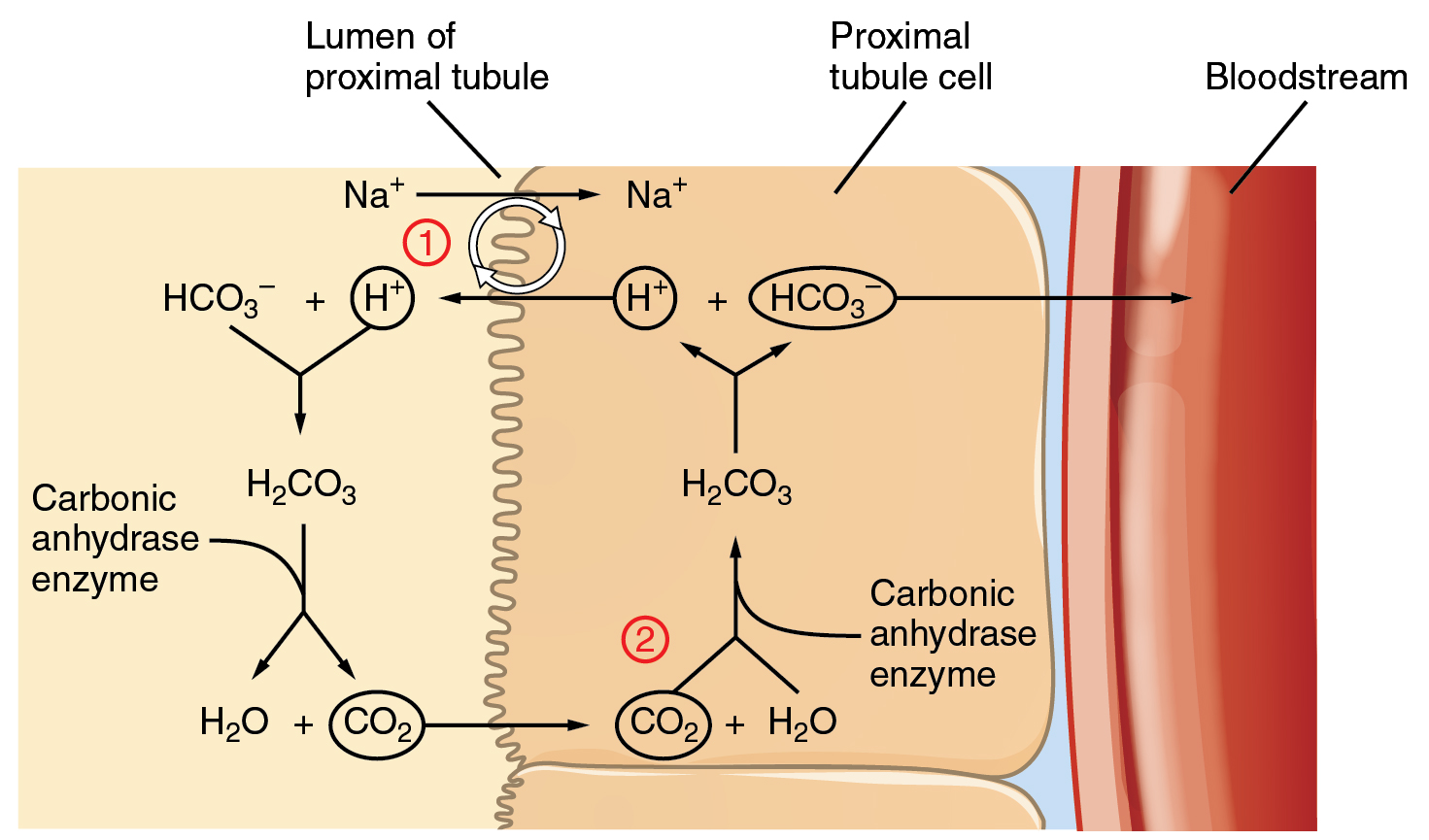

Bicarbonate ions (HCO3–), found in the filtrate, are essential to the bicarbonate buffer system, yet the cells of the tubule are not permeable to bicarbonate ions. The steps involved in supplying HCO3– to the system (Figure 82.2) are summarized below:

- Step 1: Sodium ions are reabsorbed into the blood from the filtrate in exchange for H+ by an antiport mechanism in the apical membranes of cells lining the renal tubule.

- Step 2: The cells produce bicarbonate ions that can be shunted to peritubular capillaries.

- Step 3: When CO2 is available, the reaction is driven to the formation of carbonic acid, which dissociates to form a bicarbonate ion and a hydrogen ion.

- Step 4: The bicarbonate ion passes into the peritubular capillaries and returns to the blood. The hydrogen ion is secreted into the filtrate, where it can become part of new water molecules and be reabsorbed as such, or removed in the urine.

It is also possible that salts in the filtrate, such as sulfates, phosphates, or ammonia, will capture hydrogen ions. If this occurs, the hydrogen ions will not be available to combine with bicarbonate ions and produce CO2. In such cases, bicarbonate ions are not conserved from the filtrate to the blood, which will also contribute to a pH imbalance and acidosis.

The hydrogen ions also compete with potassium to exchange with sodium in the renal tubules. If more potassium is present than normal, potassium, rather than the hydrogen ions, will be exchanged, and increased potassium enters the filtrate. When this occurs, fewer hydrogen ions in the filtrate participate in the conversion of bicarbonate into CO2 and less bicarbonate is conserved. If there is less potassium, more hydrogen ions enter the filtrate to be exchanged with sodium and more bicarbonate is conserved.

Chloride ions are important in neutralizing positive ion charges in the body. If chloride is lost, the body uses bicarbonate ions in place of the lost chloride ions. Thus, lost chloride results in an increased reabsorption of bicarbonate by the renal system.

Impact of pH Changes on Body Functions

Even slight deviations from the normal pH range can have significant impacts on the body. Enzymes, which are crucial for catalyzing biochemical reactions, are highly sensitive to pH changes. An optimal pH is necessary for maintaining their three-dimensional structure and function. Deviations from this optimal range can lead to enzyme denaturation or altered activity, disrupting metabolic processes. Additionally, pH imbalances can affect the ionization state of various molecules, influencing cellular transport mechanisms and electrical activity in nerve and muscle cells. Overall, maintaining pH homeostasis is critical for ensuring that physiological processes operate efficiently and that the body’s internal environment remains stable.

Adapted from Anatomy & Physiology by Lindsay M. Biga et al, shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, chapter 26.

sensory receptors that detect chemical stimuli

abnormally elevated levels of carbon dioxide in the blood

abnormally low levels of carbon dioxide in the blood