60 Pulmonary functions

Learning Objectives

After reading this section, you should be able to-

- Describe the major functions of the respiratory system.

- Describe the processes associated with the respiratory system (i.e., ventilation, pulmonary gas exchange, transport of gases in blood, tissue gas exchange)

- Define pulmonary ventilation, inspiration (inhalation), and expiration (exhalation).

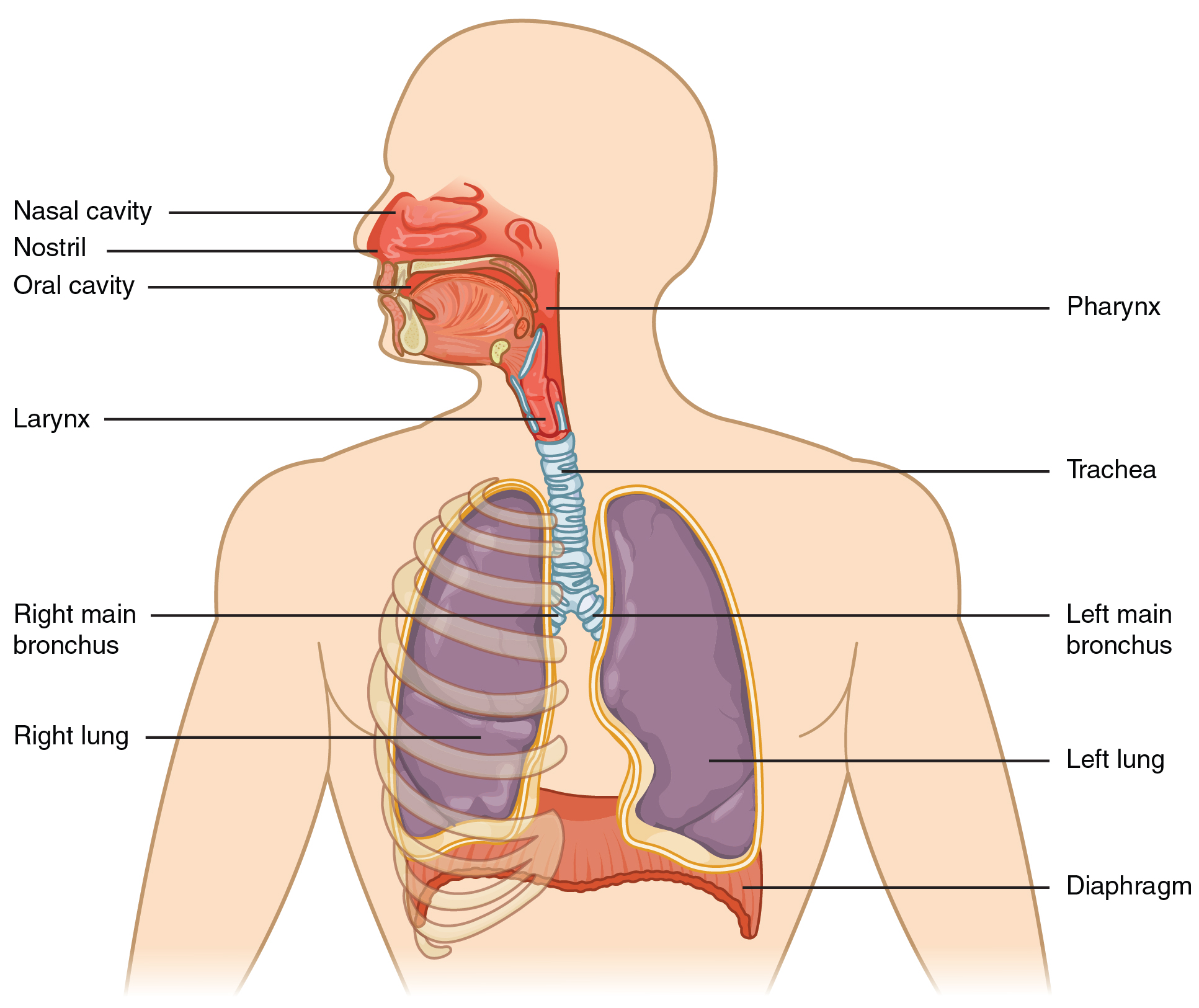

The major organs of the respiratory system function primarily to provide oxygen to body tissues for cellular respiration. This requires blood from the pulmonary circulation. This blood supply contains deoxygenated blood and travels to the lungs where erythrocytes, also known as red blood cells, pick up oxygen to be transported to tissues throughout the body. Other major functions include the removal of the waste product carbon dioxide, maintenance of acid-base balance, and the removal of heat. Portions of the respiratory system are also used for non-vital functions, such as sensing odors, speech production, and for straining, such as during childbirth or coughing (Figure 60.1). The main function of the lungs is to perform the exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide with air from the atmosphere. To this end, the lungs exchange respiratory gases across a very large epithelial surface area—about 70 square meters—that is highly permeable to gases.

Pulmonary Ventilation

Ventilation is the movement of air, while pulmonary ventilation is specifically the movement of air in and out of the lungs. The difference in pressures drives pulmonary ventilation because air flows down a pressure gradient; that is, air flows from an area of higher pressure to an area of lower pressure. Air flows into the lungs largely due to a difference in pressure; atmospheric pressure is greater than intra-alveolar pressure, and intra-alveolar pressure is greater than intrapleural pressure. Air flows out of the lungs during expiration based on the same principle; pressure within the lungs becomes greater than the atmospheric pressure.

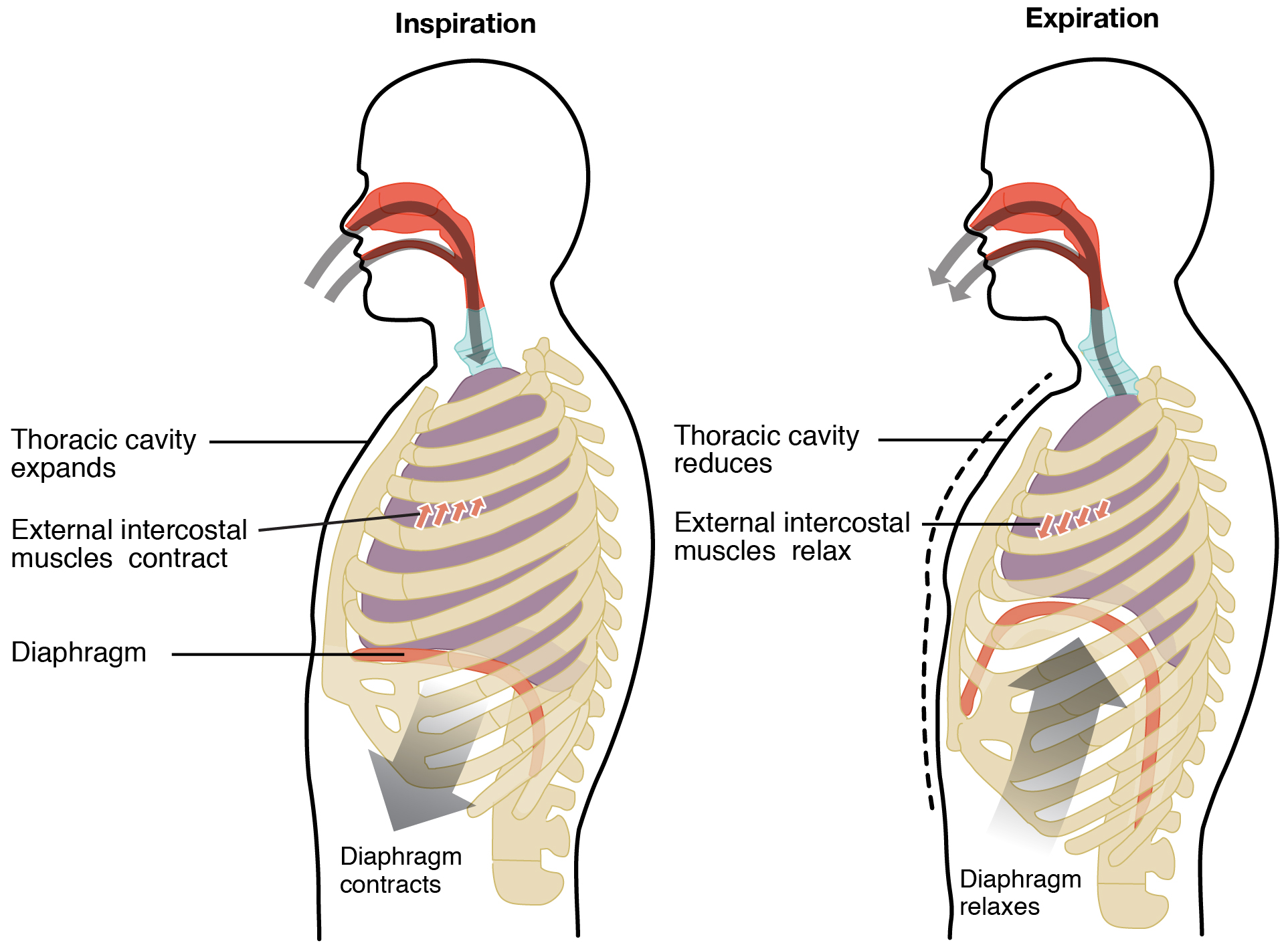

Pulmonary ventilation comprises two major steps: inspiration and expiration. Inspiration is the process that causes air to enter the lungs, and expiration is the process that causes air to leave the lungs (Figure 60.2). A respiratory cycle is one sequence of inspiration and expiration. In general, two muscle groups are used during normal inspiration: the diaphragm and the external intercostal muscles. Additional muscles can be used if a bigger breath is required. When the diaphragm contracts, it moves inferiorly toward the abdominal cavity, creating a larger thoracic cavity and more space for the lungs. Contraction of the external intercostal muscles moves the ribs upward and outward, causing the rib cage to expand, which increases the volume of the thoracic cavity. Due to the adhesive force of the pleural fluid, the expansion of the thoracic cavity forces the lungs to stretch and expand as well. This increase in volume leads to a decrease in intra-alveolar pressure, creating a pressure lower than atmospheric pressure. As a result, a pressure gradient is created that drives air into the lungs.

The process of normal expiration is passive, meaning that energy is not required to push air out of the lungs. Instead, the elasticity of the lung tissue causes the lungs to recoil, as the diaphragm and intercostal muscles relax following inspiration. In turn, the thoracic cavity and lungs decrease in volume, causing an increase in interpulmonary pressure. The interpulmonary pressure rises above atmospheric pressure, creating a pressure gradient that causes air to leave the lungs.

There are different types, or modes, of breathing that require a slightly different process to allow inspiration and expiration. Quiet breathing, also known as eupnea, is a mode of breathing that occurs at rest and does not require the cognitive thought of the individual. During quiet breathing, the diaphragm and external intercostals must contract.

A deep breath, called diaphragmatic breathing, requires the diaphragm to contract. As the diaphragm relaxes, air passively leaves the lungs. A shallow breath, called costal breathing, requires contraction of the intercostal muscles. As the intercostal muscles relax, air passively leaves the lungs.

In contrast, forced breathing, also known as hyperpnea, is a mode of breathing that can occur during exercise or actions that require the active manipulation of breathing, such as singing. During forced breathing, inspiration and expiration both occur due to muscle contractions. In addition to the contraction of the diaphragm and intercostal muscles, other accessory muscles must also contract. During forced inspiration, muscles of the neck, including the scalenes, contract and lift the thoracic wall, increasing lung volume. During forced expiration, accessory muscles of the abdomen, including the obliques, contract, forcing abdominal organs upward against the diaphragm. This helps to push the diaphragm further into the thorax, pushing more air out. In addition, accessory muscles (primarily the internal intercostals) help to compress the rib cage, which also reduces the volume of the thoracic cavity.

Gas Exchange

Gas exchange occurs at two sites in the body: in the lungs, where oxygen is picked up and carbon dioxide is released at the respiratory membrane, and at the tissues, where oxygen is released and carbon dioxide is picked up. External respiration is the exchange of gases with the external environment, and occurs in the alveoli of the lungs. Internal respiration is the exchange of gases with the internal environment, and occurs in the tissues. The actual exchange of gases occurs due to simple diffusion. Energy is not required to move oxygen or carbon dioxide across membranes. Instead, these gases follow pressure gradients that allow them to diffuse. The anatomy of the lung maximizes the diffusion of gases: The respiratory membrane is highly permeable to gases; the respiratory and blood capillary membranes are very thin, and there is a large surface area throughout the lungs.

External Respiration

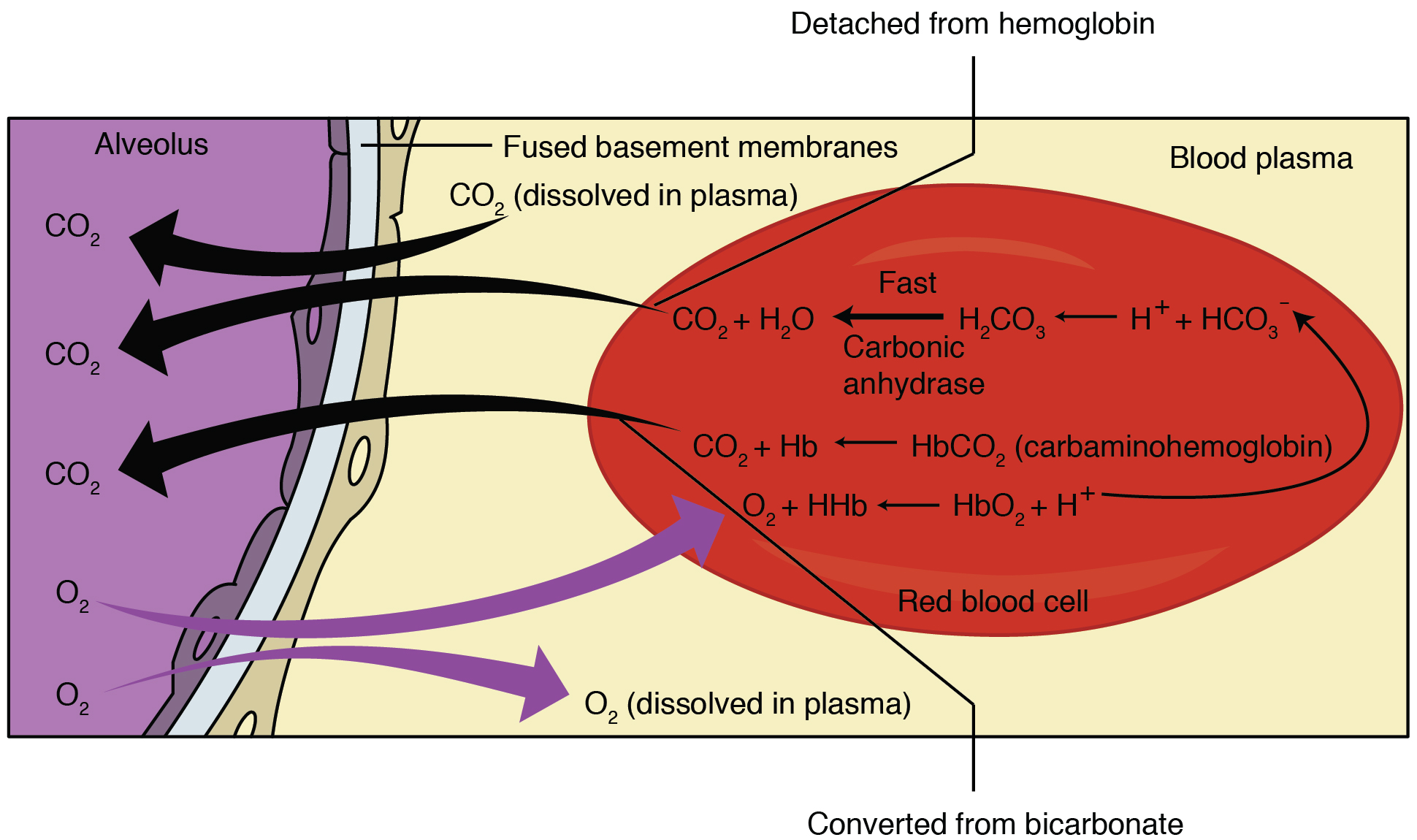

The pulmonary artery carries deoxygenated blood into the lungs from the heart, where it branches and eventually becomes the capillary network composed of pulmonary capillaries. These pulmonary capillaries create the respiratory membrane with the alveoli (Figure 60.3). As the blood is pumped through this capillary network, gas exchange occurs. Although a small amount of the oxygen is able to dissolve directly into plasma from the alveoli, most of the oxygen is picked up by erythrocytes (red blood cells) and binds to a protein called hemoglobin, a process described later in this chapter. Oxygenated hemoglobin is red, causing the overall appearance of bright red oxygenated blood, which returns to the heart through the pulmonary veins. Carbon dioxide is released in the opposite direction of oxygen, from the blood to the alveoli. Some of the carbon dioxide is returned on hemoglobin, but can also be dissolved in plasma or is present as a converted form, also explained in greater detail later in this chapter.

External respiration occurs as a function of partial pressure differences in oxygen and carbon dioxide between the alveoli and the blood in the pulmonary capillaries.

Although the solubility of oxygen in blood is not high, there is a drastic difference in the partial pressure of oxygen in the alveoli versus in the blood of the pulmonary capillaries. This large difference in partial pressure creates a very strong pressure gradient that causes oxygen to rapidly cross the respiratory membrane from the alveoli into the blood.

The partial pressure of carbon dioxide is also different between the alveolar air and the blood of the capillary. The partial pressure of carbon dioxide in the blood of the capillary is ~46 mm Hg, whereas its partial pressure in the alveoli is about 40 mm Hg. However, the solubility of carbon dioxide is much greater than that of oxygen—by a factor of about 20—in both blood and alveolar fluids. As a result, the relative concentrations of oxygen and carbon dioxide that diffuse across the respiratory membrane are similar.

Internal Respiration

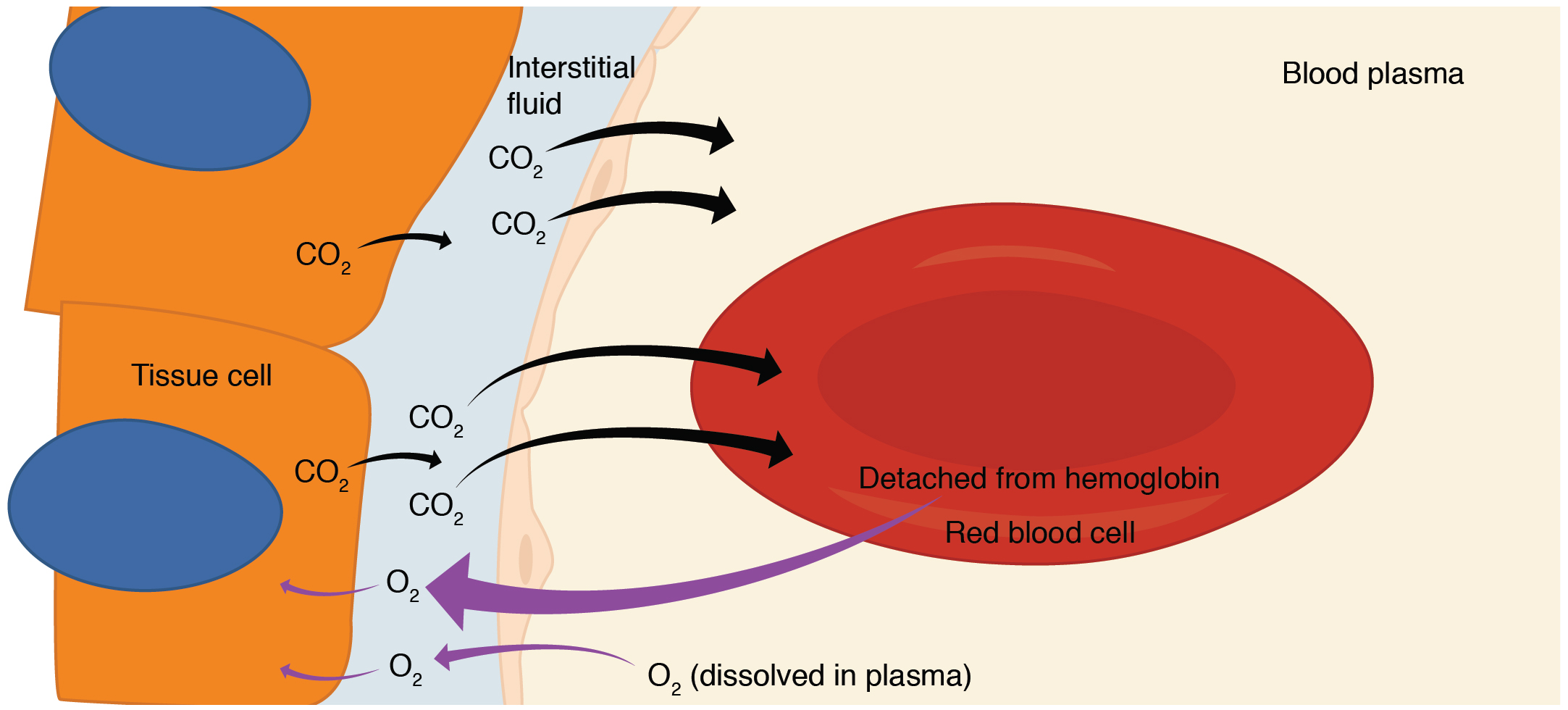

Internal respiration is gas exchange that occurs at the level of body tissues (Figure 60.4). Similar to external respiration, internal respiration also occurs as simple diffusion due to a partial pressure gradient. However, the partial pressure gradients are opposite of those present at the respiratory membrane. The partial pressure of oxygen in tissues is low, about 40 mm Hg, because oxygen is continuously used for cellular respiration. In contrast, the partial pressure of oxygen in the blood is about 100 mm Hg. This creates a pressure gradient that causes oxygen to dissociate from hemoglobin, diffuse out of the blood, cross the interstitial space, and enter the tissue.

Considering that cellular respiration continuously produces carbon dioxide, the partial pressure of carbon dioxide is lower in the blood than it is in the tissue, causing carbon dioxide to diffuse out of the tissue, cross the interstitial fluid, and enter the blood. It is then carried back to the lungs either bound to hemoglobin, dissolved in plasma, or in a converted form. By the time blood returns to the heart, the partial pressure of oxygen has returned to about 40 mm Hg, and the partial pressure of carbon dioxide has returned to ~46 mm Hg. The blood is then pumped back to the lungs to be oxygenated once again during external respiration.

Adapted from Anatomy & Physiology by Lindsay M. Biga et al, shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, chapter 22

the active process of moving air into the lungs

the passive process of moving air out of the lungs

one sequence of inspiration and expiration

eupnea; mode of breathing that occurs at rest and does not require the cognitive thought

hyperpnea; mode of breathing during which accessory muscles are involved in the process and required to contract; breathing that can occur during exercise or singing

the exchange of gases with the external environment, occurring in the alveoli of the lungs as a function of partial pressure differences in oxygen and carbon dioxide between the alveoli and blood in the pulmonary capillaries

the exchange of gases with the internal environment, occurring in the tissues due to partial pressure gradients of oxygen and carbon dioxide