6 Cell organization

Learning Objectives

After reading this section, you should be able to-

- Describe the three main parts of a cell (plasma [cell] membrane, cytoplasm, and nucleus), and explain the general functions of each part.

- Compare and contrast cytoplasm and cytosol.

- Describe the structure and roles of the cytoskeleton.

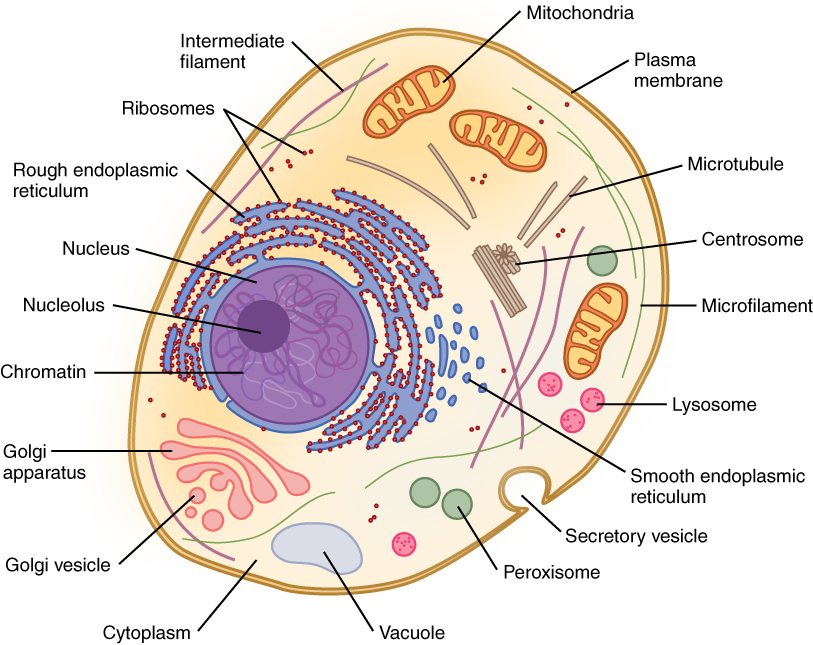

All living cells in multicellular organisms contain an internal cytoplasmic compartment, and a nucleus within the cytoplasm. The cytosol, the jelly-like substance within the cell, provides the fluid medium necessary for biochemical reactions. Eukaryotic cells, including all animal cells, also contain various cellular organelles. An organelle is one of several different types of membrane-enclosed bodies in the cell, each performing a unique function. Just as the various bodily organs work together in harmony to perform all of a human’s functions, the many different cellular organelles work together to keep the cell healthy and performing all of its important functions. The organelles and cytosol, taken together, compose the cell’s cytoplasm. The nucleus is a cell’s central organelle, which contains the cell’s DNA (Figure 6.1).

The Cytoskeleton

Much like the bony skeleton structurally supports the human body, the cytoskeleton helps the cells to maintain their structural integrity. The cytoskeleton is a group of fibrous proteins that provide structural support for cells, but this is only one of the functions of the cytoskeleton. Cytoskeletal components are also critical for cell motility, cell reproduction, and transportation of substances within the cell.

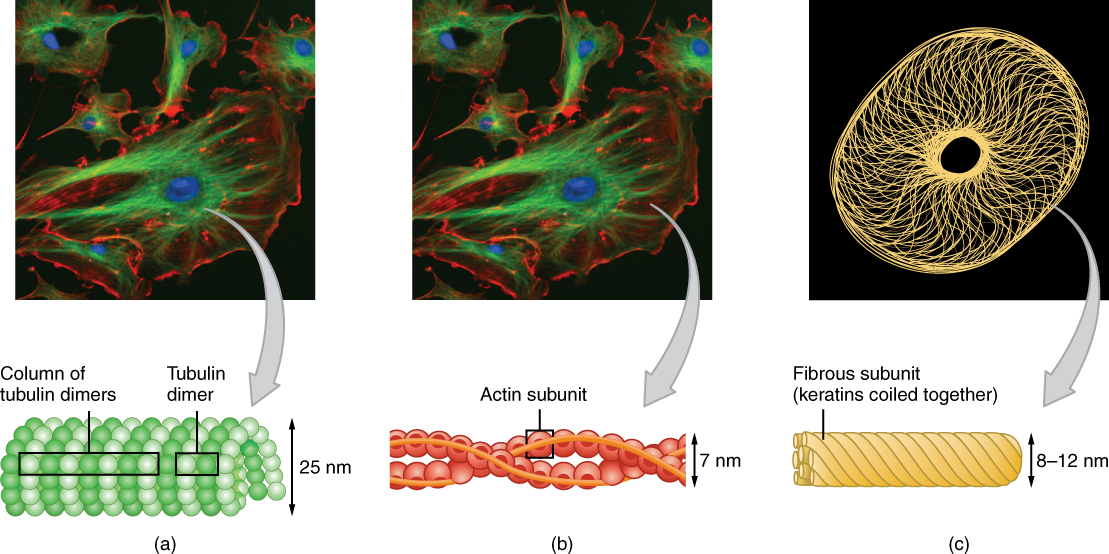

The cytoskeleton forms a complex thread-like network throughout the cell consisting of three different kinds of protein-based filaments: microfilaments, intermediate filaments, and microtubules (Figure 6.2). The thickest of the three is the microtubule, a structural filament composed of subunits of a protein called tubulin (Figure 6.2a). Microtubules maintain cell shape and structure, help resist compression of the cell, and play a role in positioning the organelles within the cell. Microtubules also make up two types of cellular appendages important for motion: cilia and flagella. Cilia are found on many cells of the body, including the epithelial cells that line the airways of the respiratory system. Cilia move rhythmically; they beat constantly, moving waste materials such as dust, mucus, and bacteria upward through the airways, away from the lungs and toward the mouth. Beating cilia on cells in the female fallopian tubes move egg cells from the ovary towards the uterus. A flagellum (plural = flagella) is an appendage larger than a cilium and specialized for cell locomotion. The only flagellated cell in humans is the sperm cell that must propel itself towards female egg cells.

A very important function of microtubules is to set the paths (somewhat like railroad tracks) along where the genetic material can be pulled (a process requiring ATP) during cell division, so that each new daughter cell receives the appropriate set of chromosomes. Two short, identical microtubule structures called centrioles are found near the nucleus of cells. A centriole can serve as the cellular origin point for microtubules extending outward as cilia or flagella assist with the separation of DNA during cell division. Microtubules grow out from the centrioles by adding more tubulin subunits, like adding additional links to a chain.

In contrast to microtubules, the microfilament is a thinner type of cytoskeletal filament (Figure 6.2b). Actin, a protein that forms chains, is the primary component of these microfilaments. Actin fibers, twisted chains of actin filaments, constitute a large component of muscle tissue and, along with the protein myosin, are responsible for muscle contraction. Like microtubules, actin filaments are long chains of single subunits (called actin subunits). In muscle cells, these long actin strands, called thin filaments, are “pulled” by thick filaments of the myosin protein to contract the cell.

Actin also has an important role during cell division. When a cell is about to split in half during cell division, actin filaments work with myosin to create a cleavage furrow that eventually splits the cell down the middle, forming two new cells from the original cell.

The final cytoskeletal filament is the intermediate filament. As its name would suggest, an intermediate filament is a filament intermediate in thickness between microtubules and microfilaments (Figure 6.2c). Intermediate filaments are made up of long fibrous subunits of a protein called keratin that are wound together like the threads that compose a rope. Intermediate filaments, in concert with the microtubules, are important for maintaining cell shape and structure. Unlike the microtubules, which resist compression, intermediate filaments resist tension—the forces that pull apart cells. There are many cases in which cells are prone to tension, such as when epithelial cells of the skin are compressed, tugging them in different directions. Intermediate filaments help anchor organelles within a cell together and also link cells to other cells by forming special cell-to-cell junctions.

Adapted from Anatomy & Physiology by Lindsay M. Biga et al, shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, chapter 3.

fluid portion of the cell made up of the cytosol and cytoplasm; where chemical reactions occur

structure within the cell that performs a specific function

cellular structure that houses fluid and organelles

the largest cellular organelle; stores genetic information that can be used to produce proteins

group of fibrous proteins that provides the cell with support, mobility, reproduction ability, and aides in the transport of different substances; composed of microtubules, microfilaments, and intermediate filaments

a component of the cytoskeleton that resists compression and helps with cellular motions; involved in mitosis

short, hairlike structures on the plasma membrane that protect the cell by trapping microorganisms

an organelle that allows for motility and locomotion

organelle near the nucleus involved in cell division; creates the mitotic spindle

thin filaments made of actin provide structure and support to the cell; during cell division, allows for separation of cells

a contractile protein; also known as the thin filament

a contractile protein; also known as the thick filament

components of the cytoskeleton that resist tension and anchor cellular organelles in place