70 Control of breathing

Learning Objectives

After reading this section you should be able to-

- Compare and contrast the central and peripheral chemoreceptors.

- Define hyperventilation, hypoventilation, panting, eupnea, hyperpnea, and apnea.

- Explain why it is possible to hold one’s breath longer after hyperventilating than after eupnea.

Respiratory Rate and Control of Ventilation

Breathing usually occurs without thought, although at times you can consciously control it, such as when you swim under water, sing a song, or blow bubbles. The respiratory rate is the total number of breaths, or respiratory cycles, that occur each minute. Respiratory rate can be an important indicator of disease, as the rate may increase or decrease during an illness or in a disease condition. The respiratory rate is controlled by the respiratory center located within the medulla oblongata in the brain, which responds primarily to changes in carbon dioxide, oxygen, and pH levels in the blood.

The normal respiratory rate of a child decreases from birth to adolescence. A child under 1 year of age has a normal respiratory rate between 30 and 60 breaths per minute, but by the time a child is about 10 years old, the normal rate is closer to 18 to 30. By adolescence, the normal respiratory rate is similar to that of adults, 12 to 18 breaths per minute.

Ventilation Control Centers

The control of ventilation is a complex interplay of multiple regions in the brain that signal the muscles used in pulmonary ventilation to contract (Table 70.1). The result is typically a rhythmic, consistent ventilation rate that provides the body with sufficient amounts of oxygen, while adequately removing carbon dioxide.

| Summary of Ventilation Regulation (Table 70.1) | |

|---|---|

| System component | Function |

| Medullary respiratory renter | Sets the basic rhythm of breathing |

| Ventral respiratory group (VRG) | Generates the breathing rhythm and integrates data coming into the medulla |

| Dorsal respiratory group (DRG) | Integrates input from the stretch receptors and the chemoreceptors in the periphery |

| Pontine respiratory group (PRG) | Influences and modifies the medulla oblongata’s functions |

| Aortic body | Monitors blood PCO2, PO2, and pH |

| Carotid body | Monitors blood PCO2, PO2, and pH |

| Hypothalamus | Monitors emotional state and body temperature |

| Cortical areas of the brain | Control voluntary breathing |

| Proprioceptors | Send impulses regarding joint and muscle movements |

| Pulmonary irritant reflexes | Protect the respiratory zones of the system from foreign material |

| Inflation reflex | Protects the lungs from over-inflating |

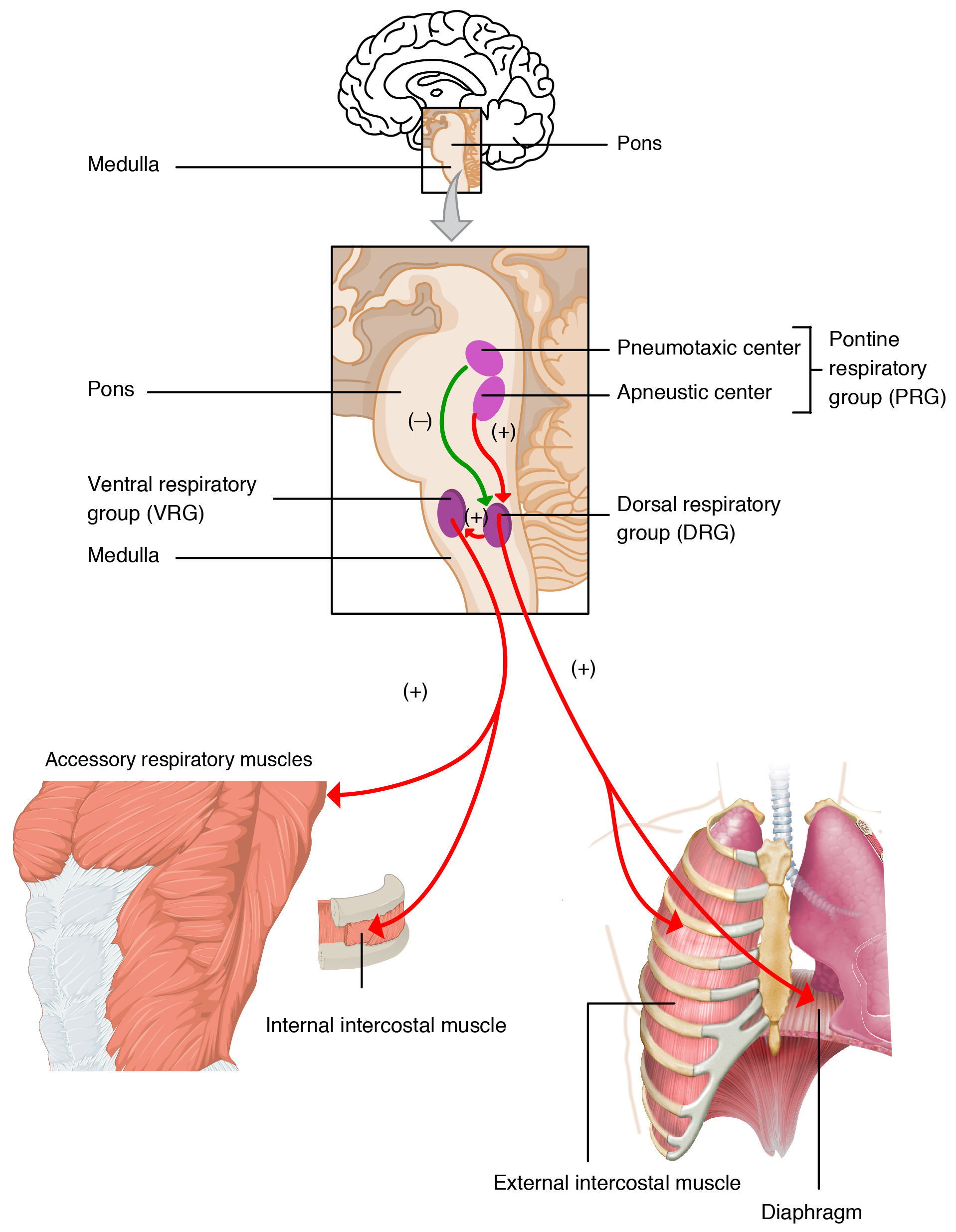

Neurons that innervate the muscles of the respiratory system are responsible for controlling and regulating pulmonary ventilation. The major brain centers involved in pulmonary ventilation are the medulla oblongata and the pontine respiratory group (Figure 70.1).

The medulla oblongata contains the dorsal respiratory group (DRG) and the ventral respiratory group (VRG). The DRG is involved in maintaining a constant breathing rhythm by stimulating the diaphragm and intercostal muscles to contract, resulting in inspiration. When activity in the DRG ceases, it no longer stimulates the diaphragm and intercostals to contract, allowing them to relax, resulting in expiration. The VRG is involved in forced breathing, as the neurons in the VRG stimulate the accessory muscles involved in forced breathing to contract, resulting in forced inspiration. The VRG also stimulates the accessory muscles involved in forced expiration to contract.

The second respiratory center of the brain is located within the pons, called the pontine respiratory group, and consists of the apneustic and pneumotaxic centers. The apneustic center is a double cluster of neuronal cell bodies that stimulate neurons in the DRG, controlling the depth of inspiration, particularly for deep breathing. The pneumotaxic center is a network of neurons that inhibits the activity of neurons in the DRG, allowing relaxation after inspiration, and thus controlling the overall rate.

Factors That Affect the Rate and Depth of Respiration

The respiratory rate and the depth of inspiration are regulated by the medulla oblongata and pons; however, these regions of the brain do so in response to systemic stimuli. It is a dose-response, positive-feedback relationship in which the greater the stimulus, the greater the response. Thus, increasing stimuli results in forced breathing. Multiple systemic factors are involved in stimulating the brain to produce pulmonary ventilation.

The major factor that stimulates the medulla oblongata and pons to produce respiration is surprisingly not oxygen concentration, but rather the concentration of carbon dioxide in the blood. As you recall, carbon dioxide is a waste product of cellular respiration and can be toxic. Concentrations of chemicals are sensed by chemoreceptors. A central chemoreceptor is one of the specialized receptors that are located in the brain and brainstem, whereas a peripheral chemoreceptor is one of the specialized receptors located in the carotid arteries and aortic arch. Concentration changes in certain substances, such as carbon dioxide or hydrogen ions, stimulate these receptors, which in turn signal the respiration centers of the brain. In the case of carbon dioxide, as the concentration of CO2 in the blood increases, it readily diffuses across the blood-brain barrier, where it collects in the extracellular fluid. As will be explained in more detail later, increased carbon dioxide levels lead to increased levels of hydrogen ions, decreasing pH. The increase in hydrogen ions in the brain triggers the central chemoreceptors to stimulate the respiratory centers to initiate contraction of the diaphragm and intercostal muscles. As a result, the rate and depth of respiration increase, allowing more carbon dioxide to be expelled, which brings more air into and out of the lungs promoting a reduction in the blood levels of carbon dioxide, and therefore hydrogen ions, in the blood. In contrast, low levels of carbon dioxide in the blood cause low levels of hydrogen ions in the brain, leading to a decrease in the rate and depth of pulmonary ventilation, producing shallow, slow breathing.

Another factor involved in influencing the respiratory activity of the brain is systemic arterial concentrations of hydrogen ions. Increasing carbon dioxide levels can lead to increased H+ levels, as mentioned above, as well as other metabolic activities, such as lactic acid accumulation after strenuous exercise. Peripheral chemoreceptors of the aortic arch and carotid arteries sense arterial levels of hydrogen ions. When peripheral chemoreceptors sense decreasing, or more acidic, pH levels, they stimulate an increase in ventilation to remove carbon dioxide from the blood at a quicker rate. Removal of carbon dioxide from the blood helps to reduce hydrogen ions, thus increasing systemic pH.

Blood levels of oxygen are also important in influencing respiratory rate. The peripheral chemoreceptors are responsible for sensing large changes in blood oxygen levels. If blood oxygen levels become quite low—about 60 mm Hg or less—then peripheral chemoreceptors stimulate an increase in respiratory activity. The chemoreceptors are only able to sense dissolved oxygen molecules, not the oxygen that is bound to hemoglobin. As you recall, the majority of oxygen is bound by hemoglobin; when dissolved levels of oxygen drop, hemoglobin releases oxygen. Therefore, a large drop in oxygen levels is required to stimulate the chemoreceptors of the aortic arch and carotid arteries.

The hypothalamus and other brain regions associated with the limbic system also play roles in influencing the regulation of breathing by interacting with the respiratory centers. The hypothalamus and other regions associated with the limbic system are involved in regulating respiration in response to emotions, pain, and temperature. For example, an increase in body temperature causes an increase in respiratory rate. Feeling excited or the fight-or-flight response will also result in an increase in respiratory rate.

At rest, the respiratory system performs its functions at a constant, rhythmic pace, as regulated by the respiratory centers of the brain. At this pace, ventilation provides sufficient oxygen to all the tissues of the body. However, there are times that the respiratory system must alter the pace of its functions in order to accommodate the oxygen demands of the body.

Types of breathing

Hyperpnea is an increased depth and rate of ventilation to meet an increase in oxygen demand as might be seen in exercise or disease, particularly diseases that target the respiratory or digestive tracts. This does not significantly alter blood oxygen or carbon dioxide levels, but merely increases the depth and rate of ventilation to meet the demand of the cells. In contrast, hyperventilation is an increased ventilation rate that is independent of the cellular oxygen needs and leads to abnormally low blood carbon dioxide levels and high (alkaline) blood pH.

Interestingly, exercise does not cause hyperpnea as one might think. Muscles that perform work during exercise do increase their demand for oxygen, stimulating an increase in ventilation. However, hyperpnea during exercise appears to occur before a drop in oxygen levels within the muscles can occur. Therefore, hyperpnea must be driven by other mechanisms, either instead of or in addition to a drop in oxygen levels. The exact mechanisms behind exercise hyperpnea are not well understood, and some hypotheses are somewhat controversial. However, in addition to low oxygen, high carbon dioxide, and low pH levels, there appears to be a complex interplay of factors related to the nervous system and the respiratory centers of the brain.

First, a conscious decision to partake in exercise, or another form of physical exertion, results in a psychological stimulus that may trigger the respiratory centers of the brain to increase ventilation. In addition, the respiratory centers of the brain may be stimulated through the activation of motor neurons that innervate muscle groups that are involved in the physical activity. Finally, physical exertion stimulates proprioceptors, which are receptors located within the muscles, joints, and tendons, which sense movement and stretching; proprioceptors thus create a stimulus that may also trigger the respiratory centers of the brain. These neural factors are consistent with the sudden increase in ventilation that is observed immediately as exercise begins. Because the respiratory centers are stimulated by psychological, motor neuron, and proprioceptor inputs throughout exercise, the fact that there is also a sudden decrease in ventilation immediately after the exercise ends when these neural stimuli cease, further supports the idea that they are involved in triggering the changes of ventilation.

Hypoventilation is a decreased ventilation rate leading to elevated blood carbon dioxide levels and low (acidic) blood pH. Panting is rapid, shallow breathing that increases ventilation rate but not depth, often seen in animals or humans to dissipate heat. Tachypnea is an abnormally rapid breathing rate, which can involve shallow or deep breaths and is often a response to conditions like fever, anxiety, or respiratory disorders. Eupnea is normal, good, unlabored breathing, typical at rest. Apnea is the cessation of breathing, often occurring temporarily during sleep (sleep apnea).

Breath Holding After Hyperventilating vs. Eupnea

Hyperventilation can extend the duration one can hold their breath compared to normal breathing (eupnea) because hyperventilation reduces the level of carbon dioxide in the blood. Since the primary drive to breathe comes from elevated carbon dioxide levels rather than low oxygen levels, lowering CO2 through hyperventilation delays the point at which the urge to breathe becomes overwhelming.

the total number of respiratory cycles (breaths) per minute

the movement of air in and out of the lungs

one of two respiratory groups in the medulla oblongata involved in maintaining constant breathing rhythms, composed of neurons that initiate inspiration

one of two respiratory groups in the medulla oblongata consisting of neurons involved in both inspiration and expiration, and which is involved in forced breathing by stimulating accessory muscles

a double cluster of neuronal cell bodies that stimulate neurons in the dorsal respiratory group of the medulla oblongata that control the depth of inspiration, particularly for deep breathing

a network of neurons that inhibits the activity of neurons in the dorsal respiratory group that control the overall rate of breathing by allowing relaxation after inspiration

specialized receptors located in the brain and brainstem that directly sense hydrogen ions and indirectly sense carbon dioxide

specialized receptors in the carotid arteries and aortic arch that sense oxygen, hydrogen ions, and carbon dioxide

an increased rate and depth of ventilation to meet increased oxygen demands

an increased ventilation rate independent of cellular oxygen demands

a sensory receptor located near a moving part of the body that interprets tissue position with movement

decreased ventilation rate leading to elevated blood carbon dioxide

rapid, shallow breathing that increases ventilation rate but not depth

abnormally rapid breathing rate

normal breathing

cessation of breathing