22 Autonomic nervous system

Learning Objectives

After reading this section, you should be able to-

- Name the two main divisions of the ANS and compare and contrast the major functions of each division, the length, myelination, neurotransmitter released and receptors of the preganglionic and postganglionic axons.

- Compare and contrast the effects (or lack thereof) of sympathetic and parasympathetic innervation on various effectors (e.g., heart, airways, gastrointestinal tract, iris of the eye, blood vessels, sweat glands, arrector pili muscles).

- Explain the relationship between chromaffin cells in the adrenal medulla and the sympathetic division of the nervous system.

- Describe visceral reflex arcs, including structural and functional details of sensory and motor (autonomic) components.

The motor branch of the nervous system can be divided into two functional parts: the somatic nervous system and the autonomic nervous system. The major differences between the two systems are evident in the responses that each produces. The somatic nervous system causes contraction of skeletal muscles. The autonomic nervous system controls cardiac and smooth muscle, as well as glandular tissue. The somatic nervous system is associated with voluntary responses (though many can happen without conscious awareness, like breathing), and the autonomic nervous system is associated with involuntary responses, such as those related to homeostasis.

The autonomic nervous system regulates many of the internal organs through a balance of two aspects, or divisions. In addition to the endocrine system, the autonomic nervous system is instrumental in homeostatic mechanisms in the body. The two divisions of the autonomic nervous system are the sympathetic division and the parasympathetic division. The sympathetic system is associated with the fight-or-flight response, and parasympathetic activity is referred to by the epithet of rest and digest. Homeostasis is the balance between the two systems. At each target effector, dual innervation determines activity. For example, the heart receives connections from both the sympathetic and parasympathetic divisions. One causes heart rate to increase, whereas the other causes heart rate to decrease.

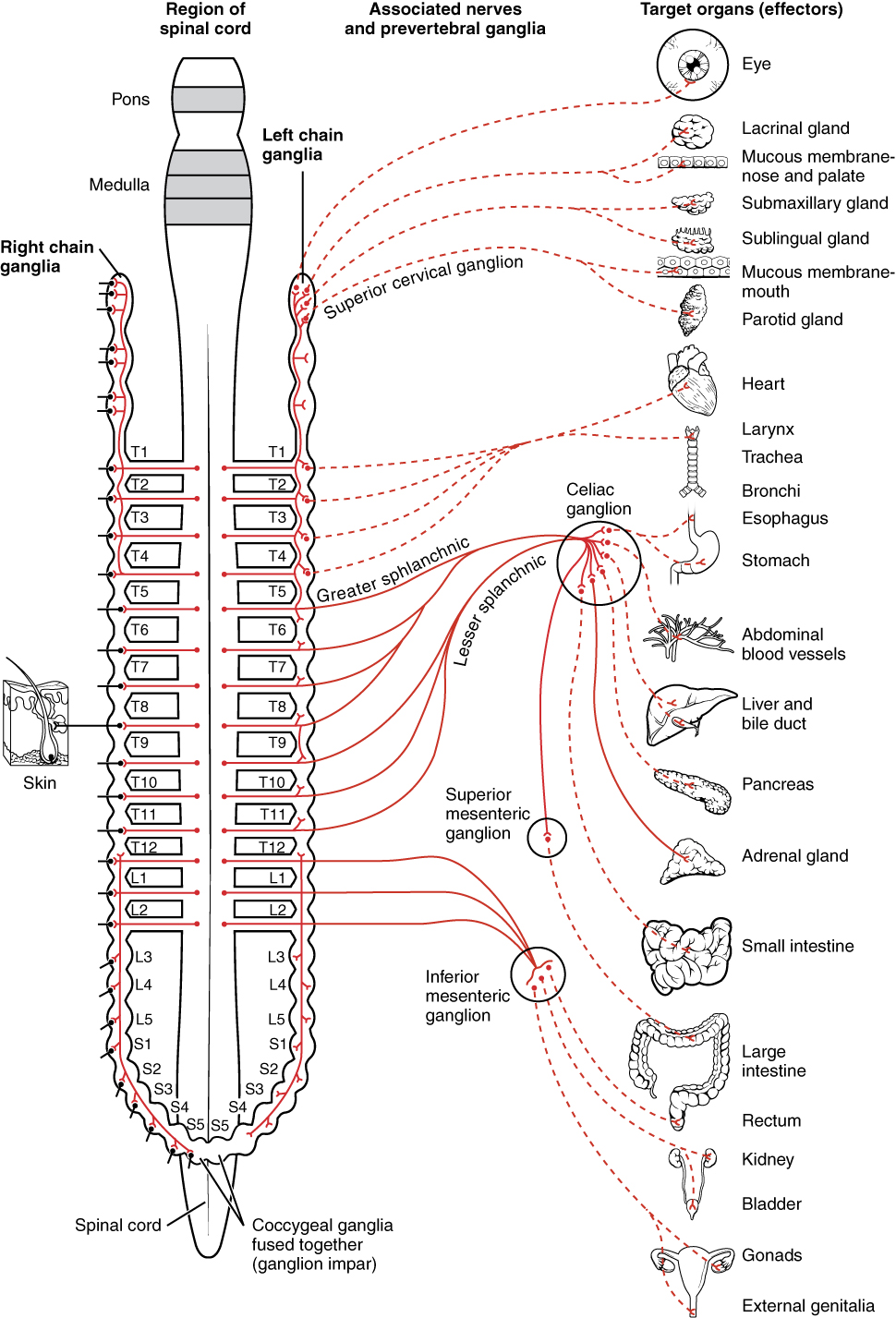

Sympathetic Division of the Autonomic Nervous System

To respond to a threat—to fight or to run away—the sympathetic system causes divergent effects as many different effector organs are activated together for a common purpose. More oxygen needs to be inhaled and delivered to skeletal muscle. The respiratory, cardiovascular, and musculoskeletal systems are all activated together. Additionally, sweating keeps the body from overheating when contracting muscles produce excess heat. The digestive system shuts down so that blood is not absorbing nutrients when it should be delivering oxygen to skeletal muscles. To coordinate all these responses, the connections in the sympathetic system diverge from a limited region of the central nervous system (CNS) to a wide array of ganglia that project to the many effector organs simultaneously. The complex set of structures that compose the output of the sympathetic system make it possible for these disparate effectors to come together in a coordinated, systemic change.

A diagram that shows that the electrical connections of the sympathetic system is somewhat like a circuit between different receptacles and devices. In Figure 22.1, the “circuits” of the sympathetic system are intentionally simplified.

An axon from the central neuron that projects to a sympathetic ganglion is referred to as a preganglionic fiber or neuron, and represents the output from the CNS to the ganglion. Because the sympathetic ganglia are adjacent to the vertebral column, preganglionic sympathetic fibers are relatively short, and they are myelinated. A postganglionic fiber—the axon from a ganglionic neuron that projects to the target effector—represents the output of a ganglion that directly influences the organ. Compared with the preganglionic fibers, postganglionic sympathetic fibers are long because of the relatively greater distance from the ganglion to the target effector. These fibers are unmyelinated. (Note that the term “postganglionic neuron” may be used to describe the projection from a ganglion to the target. The problem with that usage is that the cell body is in the ganglion, and only the fiber is postganglionic. Typically, the term neuron applies to the entire cell.)

One type of preganglionic sympathetic fiber does not terminate in a ganglion. These are the axons from central sympathetic neurons that project to the adrenal medulla, the interior portion of the adrenal gland. These axons are still referred to as preganglionic fibers, but the target is not a ganglion. The adrenal medulla releases signaling molecules into the bloodstream, rather than using axons to communicate with target structures. The cells in the adrenal medulla that are contacted by the preganglionic fibers are called chromaffin cells. These cells are neurosecretory cells that develop from the neural crest along with the sympathetic ganglia, reinforcing the idea that the gland is, functionally, a sympathetic ganglion.

The projections of the sympathetic division of the autonomic nervous system diverge widely, resulting in a broad influence of the system throughout the body. As a response to a threat, the sympathetic system would increase heart rate and breathing rate, and cause blood flow to the skeletal muscle to increase and blood flow to the digestive system to decrease. Sweat gland secretion should also increase as part of an integrated response. All of those physiological changes are going to be required to occur together to run away from the hunting lioness, or the modern equivalent. This divergence is seen in the branching patterns of preganglionic sympathetic neurons—a single preganglionic sympathetic neuron may have 10–20 targets. .

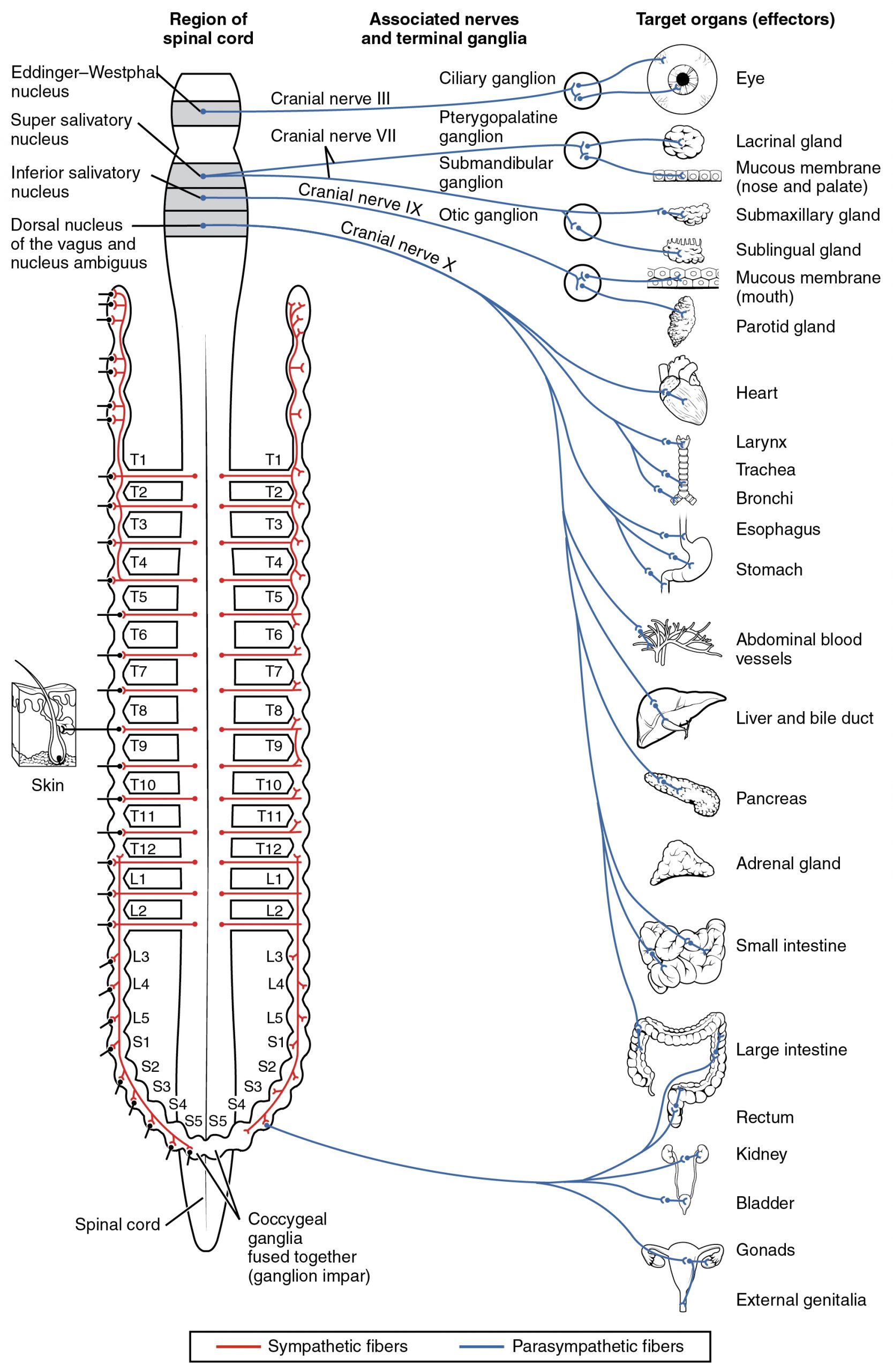

Parasympathetic Division of the Autonomic Nervous System

The parasympathetic division of the autonomic nervous system is named because its preganglionic neurons are located in the brainstem and the sacral region of the spinal cord, also referred to as the craniosacral division. The circuits of the parasympathetic division are similar to those of the sympathetic division in that both use a two-neuron pathway consisting of preganglionic and postganglionic neurons. However, a key difference is that parasympathetic ganglia are located near or within the target organs, while sympathetic ganglia are typically found near the spinal cord. Additionally, parasympathetic responses tend to be more localized, whereas sympathetic responses are more widespread. The connections, or “circuits,” of the parasympathetic division are similar to the general layout of the sympathetic division with a few specific differences (Figure 22.2). The preganglionic fibers from the cranial region travel in cranial nerves, whereas preganglionic fibers from the sacral region travel in spinal nerves. The targets of these fibers are terminal ganglia, which are located near—or even within—the target effector. These ganglia are often referred to as intramural ganglia when they are found within the walls of the target organ. The postganglionic fiber projects from the terminal ganglia a short distance to the target effector, or to the specific target tissue within the organ. Comparing the relative lengths of axons in the parasympathetic system, the preganglionic fibers are long and the postganglionic fibers are short because the ganglia are close to—and sometimes within—the target effectors.

Chemical Signaling in the Autonomic Nervous System

Having understood the cholinergic and adrenergic systems, their role in the autonomic system is relatively simple to understand. All preganglionic fibers, both sympathetic and parasympathetic, release ACh. All ganglionic neurons—the targets of these preganglionic fibers—have nicotinic receptors in their cell membranes. The nicotinic receptor is a ligand-gated cation channel that results in depolarization of the postsynaptic membrane. The postganglionic parasympathetic fibers also release ACh, but the receptors on their targets are muscarinic receptors, which are G protein–coupled receptors and do not exclusively cause depolarization of the postsynaptic membrane. Postganglionic sympathetic fibers release norepinephrine, except for fibers that project to sweat glands and to blood vessels associated with skeletal muscles, which release ACh (Table 22.1).

| Autonomic System Signaling Molecules (Table 22.1) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Sympathetic | Parasympathetic | |

| Preganglionic | Acetylcholine → nicotinic receptor | Acetylcholine → nicotinic receptor |

| Postganglionic | Norepinephrine → α- or β-adrenergic receptors

Acetylcholine → muscarinic receptor (associated with sweat glands and the blood vessels associated with skeletal muscles only

|

Acetylcholine → muscarinic receptor |

Signaling molecules can belong to two broad groups. Neurotransmitters are released at synapses, whereas hormones are released into the bloodstream. These are simplistic definitions, but they can help to clarify this point. Acetylcholine can be considered a neurotransmitter because it is released by axons at synapses. The adrenergic system, however, presents a challenge. Postganglionic sympathetic fibers release norepinephrine, which can be considered a neurotransmitter. But the adrenal medulla releases epinephrine and norepinephrine into circulation, so they should be considered hormones.

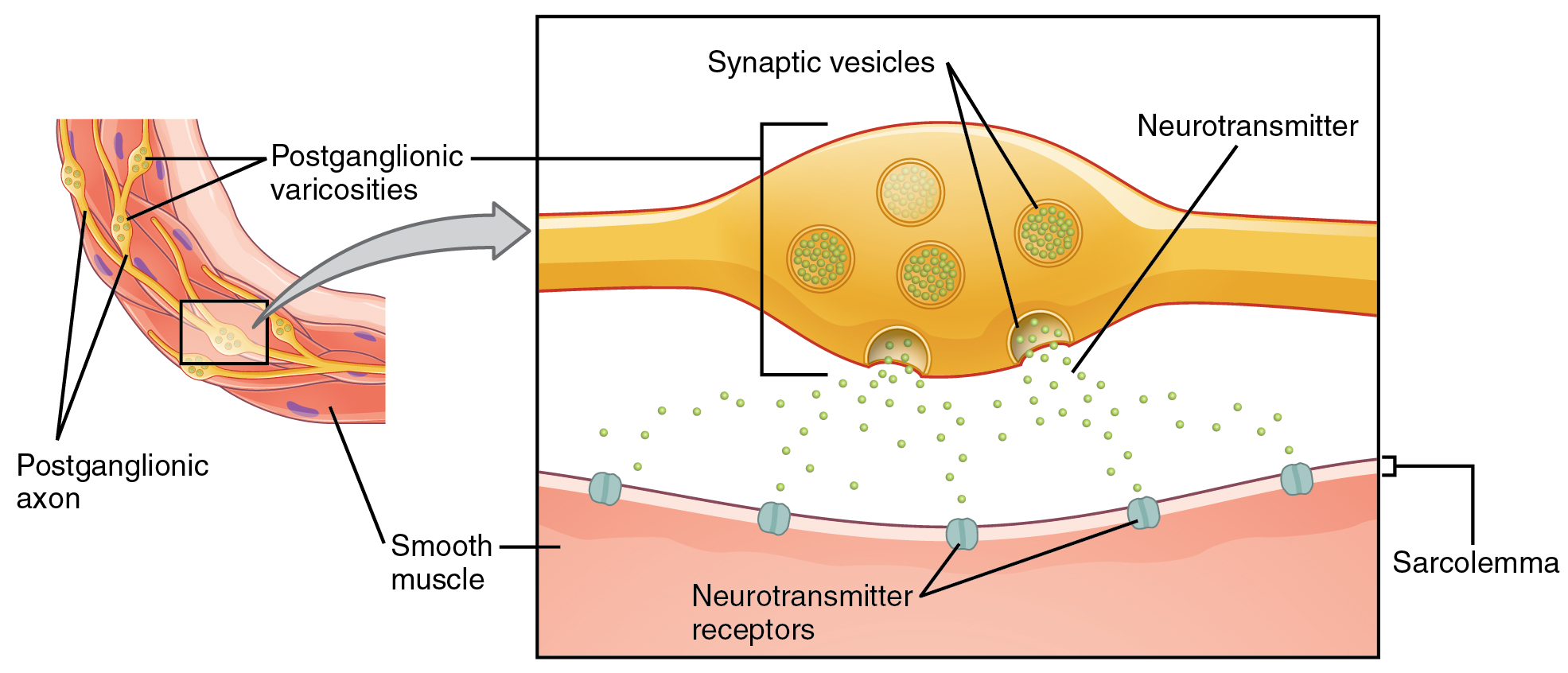

What are referred to here as synapses may not fit the strictest definition of synapse. Some sources will refer to the connection between a postganglionic fiber and a target effector as neuroeffector junctions; neurotransmitters, as defined above, would be called neuromodulators. The structure of postganglionic connections are not the typical synaptic end bulb that is found at the neuromuscular junction, but rather are chains of swellings along the length of a postganglionic fiber called a varicosity (Figure 22.3)

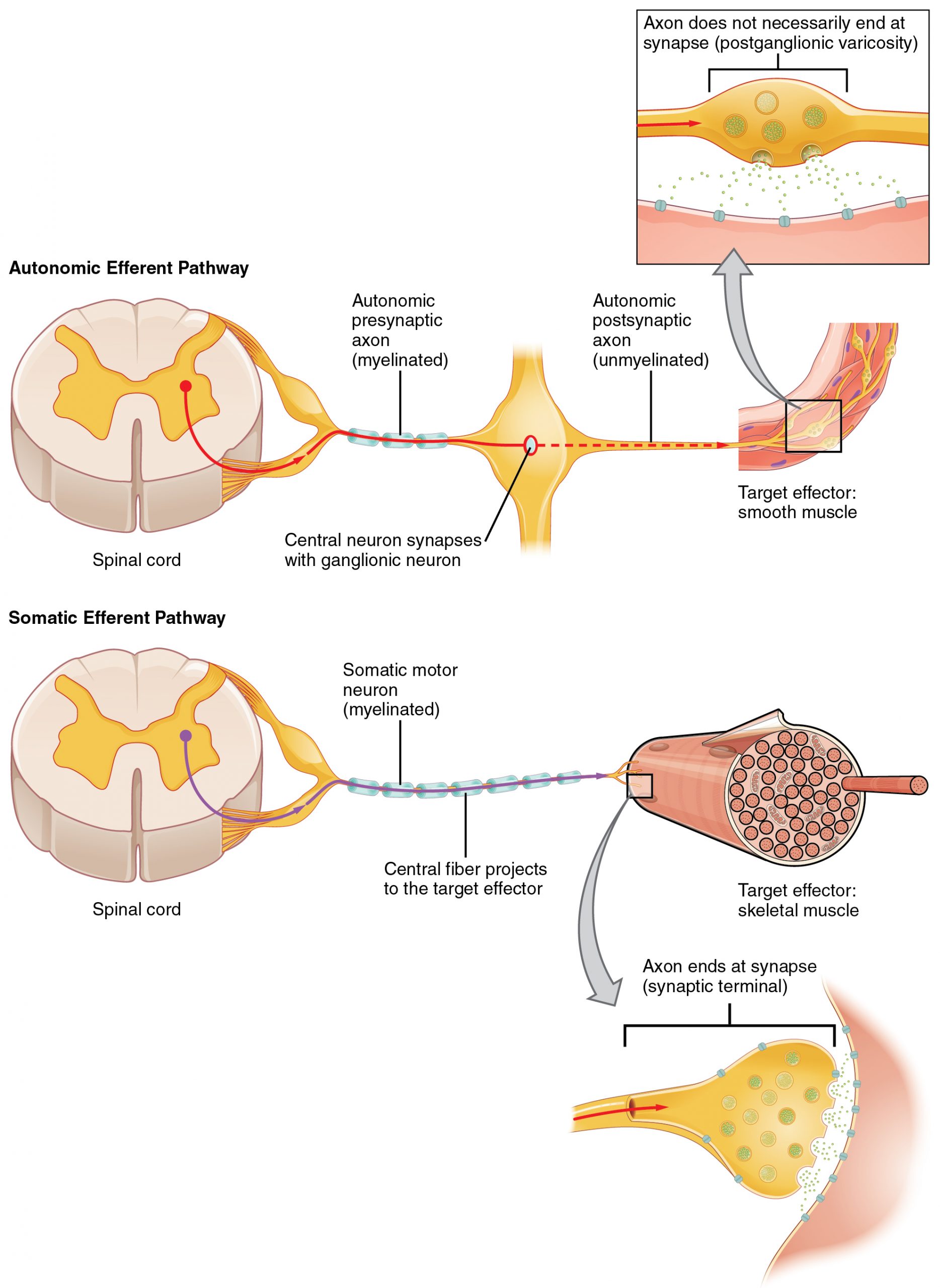

The autonomic nervous system regulates organ systems through circuits that resemble the reflexes described in the somatic nervous system. The main difference between the somatic and autonomic systems is in what target tissues are effectors. Somatic responses are solely based on skeletal muscle contraction. The autonomic system, however, targets cardiac and smooth muscle, as well as glandular tissue. Whereas the basic circuit is a reflex arc, there are differences in the structure of those reflexes for the somatic and autonomic systems.

The Structure of Reflexes – Autonomic reflexes

One difference between a somatic reflex, such as the withdrawal reflex, and a visceral reflex, which is an autonomic reflex, is in the efferent branch. The output of a somatic reflex is the lower motor neuron in the ventral horn of the spinal cord that projects directly to a skeletal muscle to cause its contraction. The output of a visceral reflex is a two-step pathway starting with the preganglionic fiber emerging from a lateral horn neuron in the spinal cord, or a cranial nucleus neuron in the brain stem, to a ganglion—followed by the postganglionic fiber projecting to a target effector. The other part of a reflex, the afferent branch, is often the same between the two systems. Sensory neurons receiving input from the periphery—with cell bodies in the sensory ganglia, either of a cranial nerve or a dorsal root ganglion adjacent to the spinal cord—project into the CNS to initiate the reflex (Figure 22.4). The Latin root “effere” means “to carry.” Adding the prefix “ef-” suggests the meaning “to carry away,” whereas adding the prefix “af-” suggests “to carry toward or inward.”

Afferent Branch

The afferent branch of a reflex arc does differ between somatic and visceral reflexes in some instances. Many of the inputs to visceral reflexes are from special or somatic senses, but particular senses are associated with the viscera that are not part of the conscious perception of the environment through the somatic nervous system. For example, there is a specific type of mechanoreceptor, called a baroreceptor, in the walls of the aorta and carotid sinuses that senses the stretch of those organs when blood volume or pressure increases. You do not have a conscious perception of having high blood pressure, but that is an important afferent branch of the cardiovascular and, particularly, vasomotor reflexes. The sensory neuron is essentially the same as any other general sensory neuron. The baroreceptor apparatus is part of the ending of a unipolar neuron that has a cell body in a sensory ganglion. The baroreceptors from the carotid arteries have axons in the glossopharyngeal nerve, and those from the aorta have axons in the vagus nerve.

Though visceral senses are not primarily a part of conscious perception, those sensations sometimes make it to conscious awareness. If a visceral sense is strong enough, it will be perceived. The sensory homunculus—the representation of the body in the primary somatosensory cortex—only has a small region allotted for the perception of internal stimuli. If you swallow a large bolus of food, for instance, you will probably feel the lump of that food as it pushes through your esophagus, or even if your stomach is distended after a large meal. If you inhale especially cold air, you can feel it as it enters your larynx and trachea. These sensations are not the same as feeling high blood pressure or blood sugar levels.

Efferent Branch

The efferent branch of the visceral reflex arc begins with the projection from the central neuron along the preganglionic fiber. This fiber then makes a synapse on the ganglionic neuron that projects to the target effector.

The effector organs that are the targets of the autonomic system range from the iris and ciliary body of the eye to the urinary bladder and reproductive organs. The thoracolumbar output, through the various sympathetic ganglia, reaches all of these organs. The cranial component of the parasympathetic system projects from the eye to part of the intestines. The sacral component picks up with the majority of the large intestine and the pelvic organs of the urinary and reproductive systems.

In contrast to the two-neuron pathway of the autonomic system, the somatic motor pathway consists of a single, long, myelinated motor neuron (Figure 22.5) that extends from the ventral horn of the spinal cord directly to the skeletal muscle. This neuron releases acetylcholine (ACh) at the neuromuscular junction, where it binds to nicotinic receptors on the muscle cell membrane to initiate contraction. This direct, fast-acting pathway allows for rapid and precise voluntary motor control. This direct somatic motor pathway is simpler and faster than autonomic reflex arcs, which rely on a two-neuron chain to reach their target effectors.

Balance in Competing Autonomic Reflex Arcs

The autonomic nervous system is important for homeostasis because its two divisions compete at the target effector. The balance of homeostasis is attributable to the competing inputs from the sympathetic and parasympathetic divisions (dual innervation). At the level of the target effector, the signal of which system is sending the message is strictly chemical. A signaling molecule binds to a receptor that causes changes in the target cell, which in turn causes the tissue or organ to respond to the changing conditions of the body.

Competing Neurotransmitters

The postganglionic fibers of the sympathetic and parasympathetic divisions both release neurotransmitters that bind to receptors on their targets. Postganglionic sympathetic fibers release norepinephrine, with a minor exception, whereas postganglionic parasympathetic fibers release ACh. For any given target, the difference in which division of the autonomic nervous system is exerting control is in what chemical binds to its receptors. The target cells will have adrenergic and muscarinic receptors. If norepinephrine is released, it will bind to the adrenergic receptors present on the target cell, and if ACh is released, it will bind to the muscarinic receptors on the target cell.

In the sympathetic system, there are exceptions to this pattern of dual innervation. The postganglionic sympathetic fibers that contact the blood vessels within skeletal muscle and that contact sweat glands do not release norepinephrine, they release ACh. This does not create any problem because there is no parasympathetic input to the sweat glands. Sweat glands have muscarinic receptors and produce and secrete sweat in response to the presence of ACh.

At most of the other targets of the autonomic system, the effector response is based on which neurotransmitter is released and what receptor is present. For example, regions of the heart that establish heart rate are contacted by postganglionic fibers from both systems. If norepinephrine is released onto those cells, it binds to an adrenergic receptor that causes the cells to depolarize faster, and the heart rate increases. If ACh is released onto those cells, it binds to a muscarinic receptor that causes the cells to hyperpolarize so that they cannot reach threshold as easily, and the heart rate slows. Without this parasympathetic input, the heart would work at a rate of approximately 100 beats per minute (bpm). The sympathetic system speeds that up, as it would during exercise, to 120–140 bpm, for example. The parasympathetic system slows it down to the resting heart rate of 60–80 bpm.

Autonomic tone

Organ systems are balanced between the input from the sympathetic and parasympathetic divisions. When something upsets that balance, the homeostatic mechanisms strive to return it to its regular state. For each organ system, there may be more of a sympathetic or parasympathetic tendency to the resting state, which is known as the autonomic tone of the system. For example, the heart rate described above. Because resting heart rate is the result of the parasympathetic system slowing the heart down from its intrinsic rate of 100 bpm, the heart can be said to have a greater natural parasympathetic tone.

In a similar fashion, another aspect of the cardiovascular system is primarily under sympathetic control. Blood pressure is partially determined by the contraction of smooth muscle in the walls of blood vessels. These tissues have adrenergic receptors that respond to the release of norepinephrine from postganglionic sympathetic fibers by constricting and increasing blood pressure. The hormones released from the adrenal medulla—epinephrine and norepinephrine—will also bind to these receptors. Those hormones travel through the bloodstream where they can easily interact with the receptors in the vessel walls. The parasympathetic system has no significant input to the systemic blood vessels, so the sympathetic system determines their tone.

There are a limited number of blood vessels that respond to sympathetic input in a different fashion. Blood vessels in skeletal muscle, particularly those in the lower limbs, are more likely to dilate. It does not have an overall effect on blood pressure to alter the tone of the vessels, but rather allows for blood flow to increase for those skeletal muscles that will be active in the fight-or-flight response. The blood vessels that have a parasympathetic projection are limited to those in the erectile tissue of the reproductive organs. Acetylcholine released by these postganglionic parasympathetic fibers cause the vessels to dilate, leading to the engorgement of the erectile tissue.

Adapted from Anatomy & Physiology by Lindsay M. Biga et al, shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, chapter 12.

the fight or flight division of the autonomic nervous system; the division of the autonomic nervous system that responds to stressful situations

the division of the autonomic nervous system associated with rest and digest; the division of the autonomic nervous system that conserves energy

physiological responses to dangerous or stressful situations, such as increased heart rate, bloop pressure, and ventilation; associated with the sympathetic division of the autonomic nervous system

physiological responses to quiet or peaceful situations, such as decreased heart rate, bloop pressure, and ventilation; associated with the parasympathetic division of the autonomic nervous system

an axon from the central neuron that projects to a sympathetic ganglion

an axon from a ganglionic neuron that projects to the target effector

the interior part of the adrenal gland, responsible for controlling hormones that initiate the sympathetic response

cells in the adrenal medulla that are contacted by preganglionic fibers to make and secrete hormones

a parasympathetic ganglion that is situated near or on the organ that it innervates

terminal ganglia within the walls of the target organ it innervates

The site of communication between a neuron and another cell

swollen structures along the length of postganglionic fiber

the pathway of a reflex response, consisting of a stimulus, sensory receptor, afferent neuron, integration center, efferent neuron, effector organ, and response

a reflex involving skeletal muscle

a reflex controlled by the autonomic nervous system

the pathway that takes a response from the integration center to the effector; the output branch

the pathway that takes a response from the sensory receptor to the integration center; the input branch

a type of mechanoreceptor in the walls of the aorta and carotid sinuses that sense changes in pressure due to changes in blood volume

the natural resting tendency of an organ system to experience more of a sympathetic or parasympathetic tone