57 Baroreflex

Learning Objectives

At the end of this chapter, you should be able to-

- Explain the steps of the baroreceptor reflex and describe how this reflex maintains blood pressure homeostasis when blood pressure changes.

- Explain the role of the autonomic nervous system in regulation of blood pressure and volume.

In order to maintain homeostasis in the cardiovascular system and provide adequate blood to the tissues, blood flow must be redirected continually to the tissues as they become more active. In a very real sense, the cardiovascular system engages in resource allocation, because there is not enough blood flow to distribute blood equally to all tissues simultaneously. For example, when an individual is exercising, more blood will be directed to skeletal muscles, the heart, and the lungs. Following a meal, more blood is directed to the digestive system. Only the brain receives a more or less constant supply of blood whether you are active, resting, thinking, or engaged in any other activity.

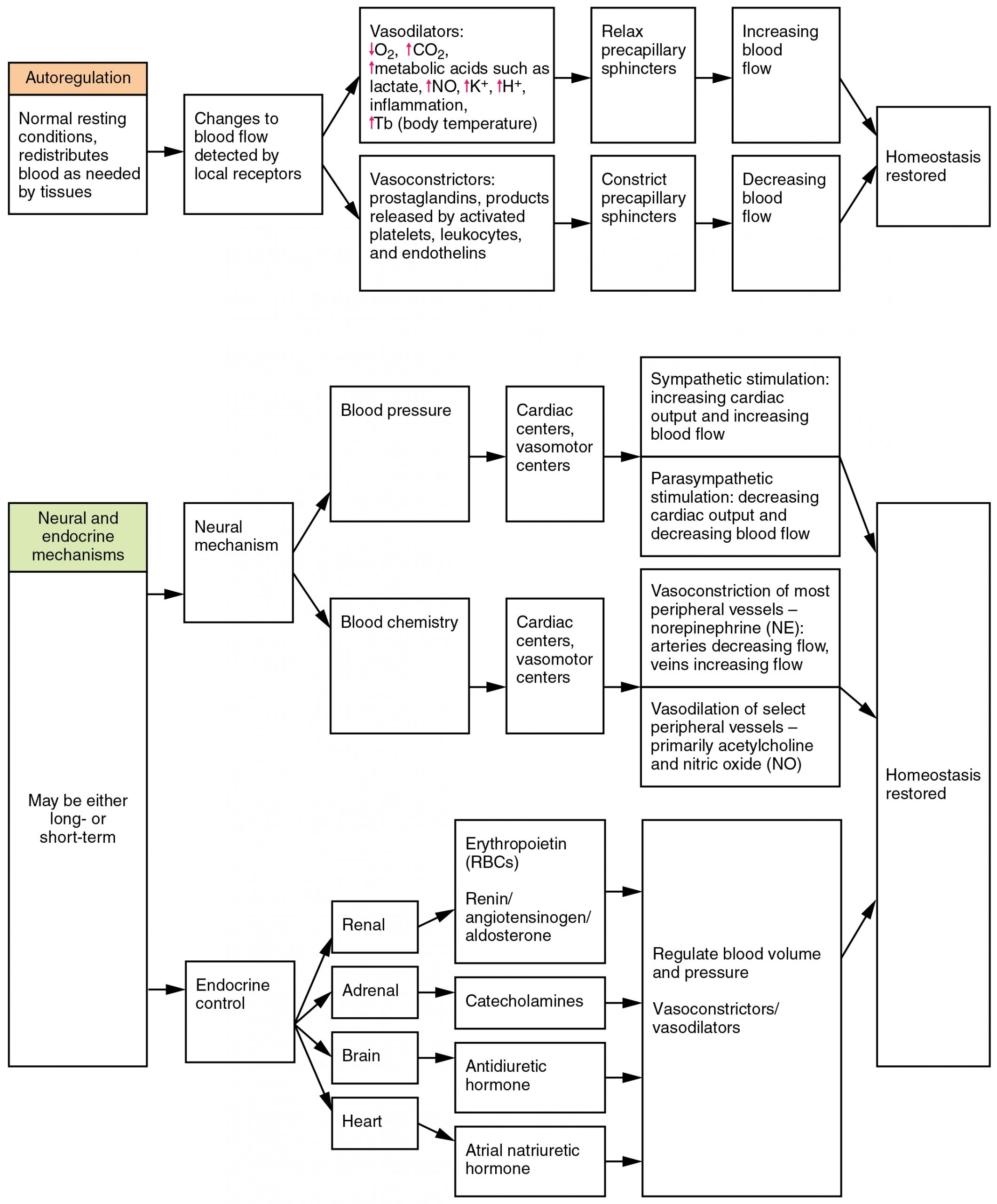

Three homeostatic mechanisms ensure adequate blood flow, blood pressure, distribution, and ultimately perfusion: neural, endocrine, and autoregulatory mechanisms. They are summarized in Figure 56.1.

Neural Regulation

The nervous system plays a critical role in the regulation of vascular homeostasis. The primary regulatory sites include the cardiovascular centers in the brain that control both cardiac and vascular functions. In addition, more generalized neural responses from the limbic system and the autonomic nervous system are factors.

The Cardiovascular Centers in the Brain

Neurological regulation of blood pressure and flow depends on the cardiovascular centers located in the medulla oblongata. This cluster of neurons responds to changes in blood pressure as well as blood concentrations of oxygen, carbon dioxide, and hydrogen ions. The cardiovascular center contains three distinct paired components:

- The cardioaccelerator centers stimulate cardiac function by regulating heart rate and stroke volume via sympathetic stimulation from the cardiac accelerator nerve.

- The cardioinhibitor centers slow cardiac function by decreasing heart rate and stroke volume via parasympathetic stimulation from the vagus nerve.

- The vasomotor centers control vessel tone, or contraction, of the smooth muscle. Changes in diameter affect peripheral resistance, pressure, and flow, which affect cardiac output. The majority of these neurons act via the release of the neurotransmitter norepinephrine from sympathetic neurons.

Baroreceptor Reflexes

Baroreceptors are specialized stretch receptors located within thin areas of blood vessels and heart chambers that respond to the degree of stretch caused by the presence of blood. They send impulses to the cardiovascular center to regulate blood pressure. Vascular baroreceptors are found primarily in sinuses (small cavities) within the aorta and carotid arteries: The aortic sinuses are found in the walls of the ascending aorta just superior to the aortic valve, whereas the carotid sinuses are in the base of the internal carotid arteries. There are also low-pressure baroreceptors located in the walls of the venae cavae and right atrium.

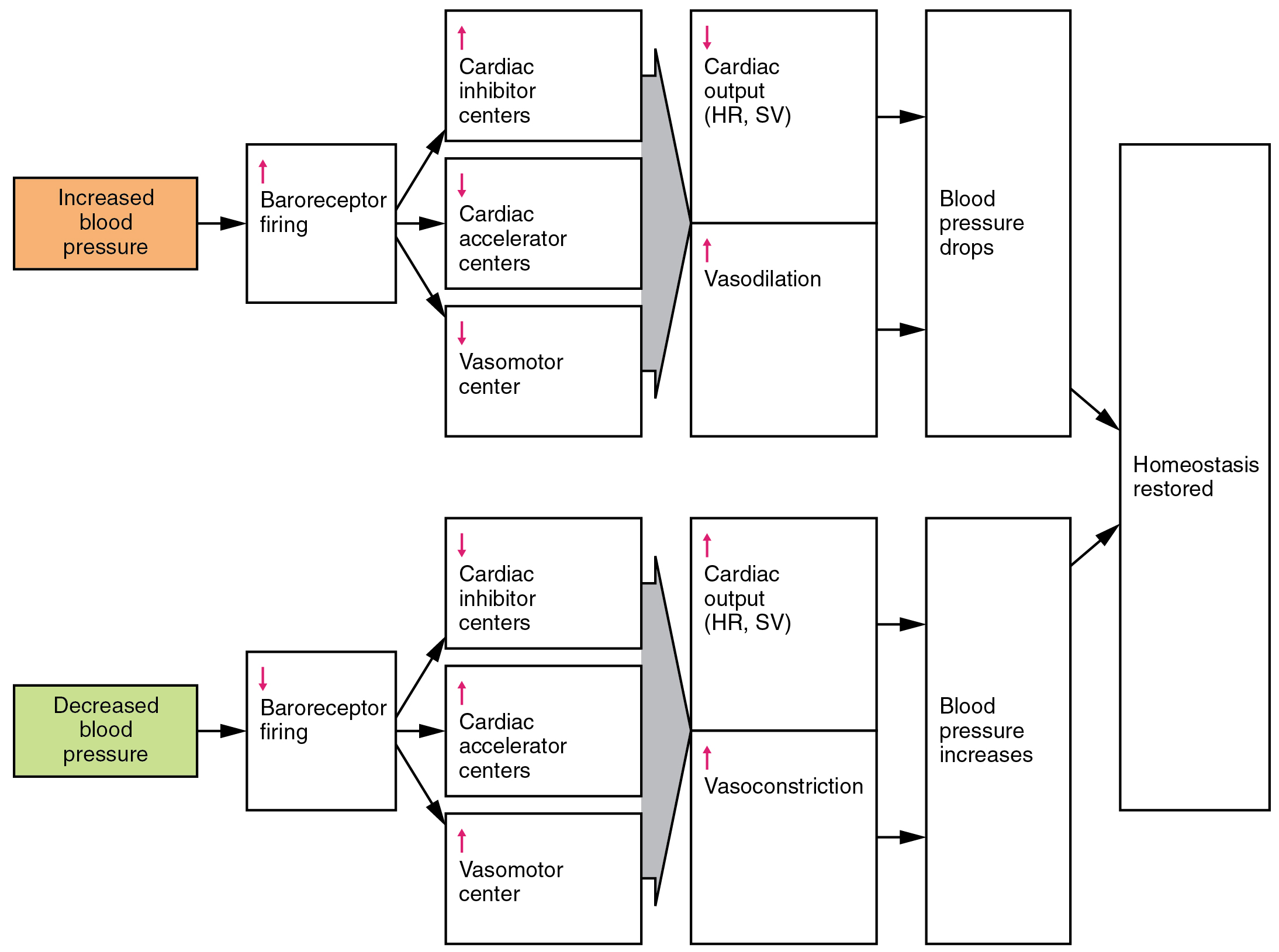

When blood pressure increases, the baroreceptors are stretched more tightly and initiate action potentials at a higher rate. At lower blood pressures, the degree of stretch is lower and the rate of firing is slower. When the cardiovascular center in the medulla oblongata receives this input, it triggers a reflex that maintains homeostasis (Figure 56.2):

- When blood pressure rises too high, the baroreceptors fire at a higher rate and trigger parasympathetic stimulation of the heart. As a result, cardiac output falls. Sympathetic stimulation of the peripheral arterioles will also decrease, resulting in vasodilation. Combined, these activities cause blood pressure to fall.

- When blood pressure drops too low, the rate of baroreceptor firing decreases. This will trigger an increase in sympathetic stimulation of the heart, causing cardiac output to increase. It will also trigger increased sympathetic stimulation of the peripheral vessels, resulting in vasoconstriction. Combined, these activities cause blood pressure to rise (Table 56.1).

| Target | Sympathetic Nervous System (SNS) | Parasympathetic Nervous System (PNS) |

|---|---|---|

| Heart rate (HR) | Increases (via SA node β-adrenergic receptors, ↑ norepinephrine) | Decreases (via SA node muscarinic receptors, ↑ acetylcholine) |

| Stroke volume (SV) | Increases (via ventricular contractility, ↑ β-adrenergic stimulation) | No significant effect |

| Peripheral resistance (TPR) | Increases (via arteriole vasoconstriction, ↑ α-adrenergic receptors, ↑ epinephrine, ↑ angiotensin II) | No significant effect |

| Overall MAP effect | Raises MAP | Lowers MAP (mainly via decreased HR) |

Imagine you are lying down and then suddenly stand up. Gravity pulls blood toward your legs, and less blood returns to your heart. As a result, blood pressure drops (mean arterial pressure decreases), and baroreceptors in the aortic arch and carotid sinus detect less stretch.

This leads to:

-

Decreased baroreceptor firing rate → medulla receives the signal that blood pressure is low.

-

Increased sympathetic nervous system activity → raises heart rate (HR), increases stroke volume (SV) by boosting ventricular contractility, and causes vasoconstriction (increased total peripheral resistance, TPR).

-

Decreased parasympathetic activity → removes the brake on HR.

Combined, these changes raise cardiac output and peripheral resistance, bringing mean arterial pressure (MAP) back up toward normal.

This reflexive adjustment happens in seconds, preventing dizziness or fainting when you change positions.

The baroreceptors in the venae cavae and right atrium monitor blood pressure as the blood returns to the heart from the systemic circulation. Normally, blood flow into the aorta is the same as blood flow back into the right atrium. If blood is returning to the right atrium more rapidly than it is being ejected from the left ventricle, the atrial receptors will stimulate the cardiovascular centers to increase sympathetic firing and increase cardiac output until homeostasis is achieved. The opposite is also true. This mechanism is referred to as the atrial reflex.

Chemoreceptor Reflexes

In addition to the baroreceptors are chemoreceptors that monitor levels of oxygen, carbon dioxide, and hydrogen ions (pH), and thereby contribute to vascular homeostasis. Chemoreceptors monitoring the blood are located in close proximity to the baroreceptors in the aortic and carotid sinuses. They signal the cardiovascular center as well as the respiratory centers in the medulla oblongata.

Since tissues consume oxygen and produce carbon dioxide and acids as waste products, when the body is more active, oxygen levels fall and carbon dioxide levels rise as cells undergo cellular respiration to meet the energy needs of activities. This causes more hydrogen ions to be produced, causing the blood pH to drop. When the body is resting, oxygen levels are higher, carbon dioxide levels are lower, more hydrogen is bound, and pH rises. (Seek additional content for more detail about pH.)

The chemoreceptors respond to increasing carbon dioxide and hydrogen ion levels (falling pH) by stimulating the cardioaccelerator and vasomotor centers, increasing cardiac output and constricting peripheral vessels. The cardioinhibitor centers are suppressed. With falling carbon dioxide and hydrogen ion levels (increasing pH), the cardioinhibitor centers are stimulated, and the cardioaccelerator and vasomotor centers are suppressed, decreasing cardiac output and causing peripheral vasodilation. In order to maintain adequate supplies of oxygen to the cells and remove waste products such as carbon dioxide, it is essential that the respiratory system respond to changing metabolic demands. In turn, the cardiovascular system will transport these gases to the lungs for exchange, again in accordance with metabolic demands. This interrelationship of cardiovascular and respiratory control cannot be overemphasized.

Other neural mechanisms can also have a significant impact on cardiovascular function. These include the limbic system that links physiological responses to psychological stimuli, as well as generalized sympathetic and parasympathetic stimulation.

Endocrine Regulation

Endocrine control over the cardiovascular system involves the catecholamines, epinephrine and norepinephrine, as well as several hormones that interact with the kidneys in the regulation of blood volume.

Epinephrine and Norepinephrine

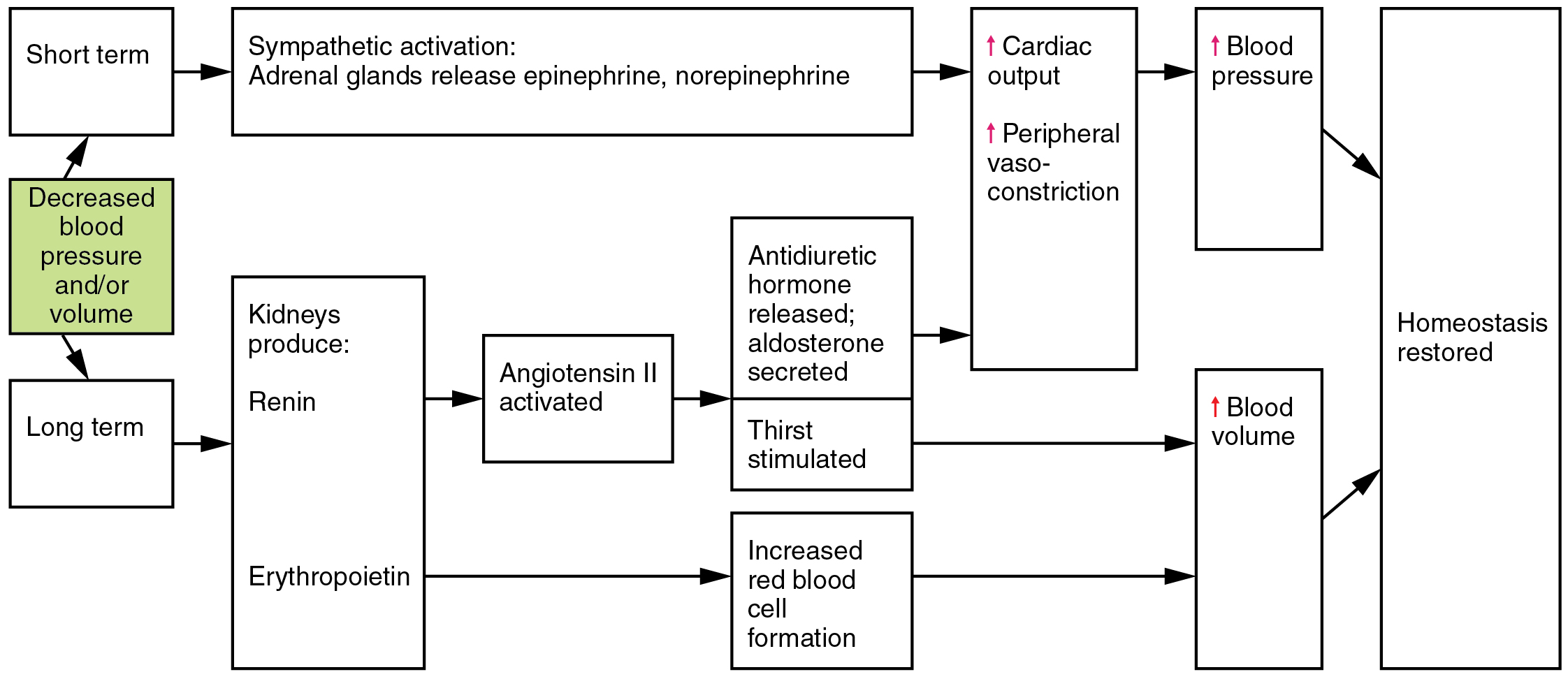

The catecholamines epinephrine and norepinephrine are released by the adrenal medulla, and enhance and extend the body’s sympathetic or “fight-or-flight” response (Figure 56.3). They increase heart rate and force of contraction, while temporarily constricting blood vessels to organs not essential for flight-or-fight responses and redirecting blood flow to the liver, muscles, and heart.

Antidiuretic Hormone

Antidiuretic hormone (ADH), also known as vasopressin, is secreted by the cells in the hypothalamus and transported to the posterior pituitary where it is stored until released upon nervous stimulation. The primary trigger prompting the hypothalamus to release ADH is increasing osmolarity of tissue fluid, usually in response to significant loss of blood volume. ADH signals its target cells in the kidneys to reabsorb more water, thus preventing the loss of additional fluid in the urine. This will increase overall fluid levels and help restore blood volume and pressure. In addition, ADH constricts peripheral vessels.

Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone Mechanism

The renin-angiotensin-aldosterone mechanism has a major effect upon the cardiovascular system (Figure 56.3). Renin is an enzyme, although because of its importance in the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone pathway, some sources identify it as a hormone. Specialized cells in the kidneys found in the juxtaglomerular apparatus respond to decreased blood flow by secreting renin into the blood. Renin converts the plasma protein angiotensinogen, which is produced by the liver, into its active form—angiotensin I. Angiotensin I circulates in the blood and is then converted into angiotensin II in the lungs. This reaction is catalyzed by the enzyme angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE).

Angiotensin II is a powerful vasoconstrictor, greatly increasing blood pressure. It also stimulates the release of ADH and aldosterone, a hormone produced by the adrenal cortex. Aldosterone increases the reabsorption of sodium into the blood by the kidneys. Since water follows sodium, this increases the reabsorption of water. This in turn increases blood volume, raising blood pressure. Angiotensin II also stimulates the thirst center in the hypothalamus, so an individual will likely consume more fluids, again increasing blood volume and pressure.

Atrial Natriuretic Hormone

Secreted by cells in the atria of the heart, atrial natriuretic hormone (ANH) (also known as atrial natriuretic peptide) is secreted when blood volume is high enough to cause extreme stretching of the cardiac cells. Cells in the ventricle produce a hormone with similar effects, called B-type natriuretic hormone. Natriuretic hormones are antagonists to angiotensin II. They promote loss of sodium and water from the kidneys, and suppress renin, aldosterone, and ADH production and release. All of these actions promote loss of fluid from the body, so blood volume and blood pressure drop.

Adapted from Anatomy & Physiology by Lindsay M. Biga et al, shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, chapter 20

specialized stretch receptors located within thin areas of blood vessels and heart chambers that respond to the degree of stretch caused by the presence of blood

an increase in heart rate as a response to increased blood pressure

sensory receptors responsible for responding to chemical stimuli

a hormone produced by the hypothalamus and stored/secreted by the posterior pituitary that acts on the collecting ducts of the kidneys to cause water reabsorption