78 Body fluid compartments

Learning Objectives

After reading this section you should be able to-

- Compare and contrast total body water (TBW) volumes in normal adult males and females.

- Compare and contrast relative volumes and osmolarities of intracellular fluid (ICF) and extracellular fluid (ECF).

- Explain the subdivision of the extracellular fluid (ECF) compartment into plasma and interstitial fluid (IF), and compare volumes and composition of plasma and IF.

- Describe the boundary walls that separate different body fluid compartments and list transport mechanisms by which water and other substances move between compartments

The chemical reactions of life take place in aqueous solutions. The dissolved substances in a solution are called solutes. In the human body, solutes vary in different parts of the body, but may include proteins—including those that transport lipids, carbohydrates, and, very importantly, electrolytes. Often in medicine, an electrolyte is referred to as a mineral dissociated from a salt that carries an electrical charge (an ion). For instance, sodium ions (Na+) and chloride ions (Cl–) are often referred to as electrolytes.

In the body, water moves through semi-permeable membranes of cells and from one compartment of the body to another by a process called osmosis. Osmosis is basically the diffusion of water from regions of higher concentration to regions of lower concentration, along an osmotic gradient across a semi-permeable membrane. As a result, water will move into and out of cells and tissues, depending on the relative concentrations of the water and solutes found there. An appropriate balance of solutes inside and outside of cells must be maintained to ensure normal function.

Body Water Content

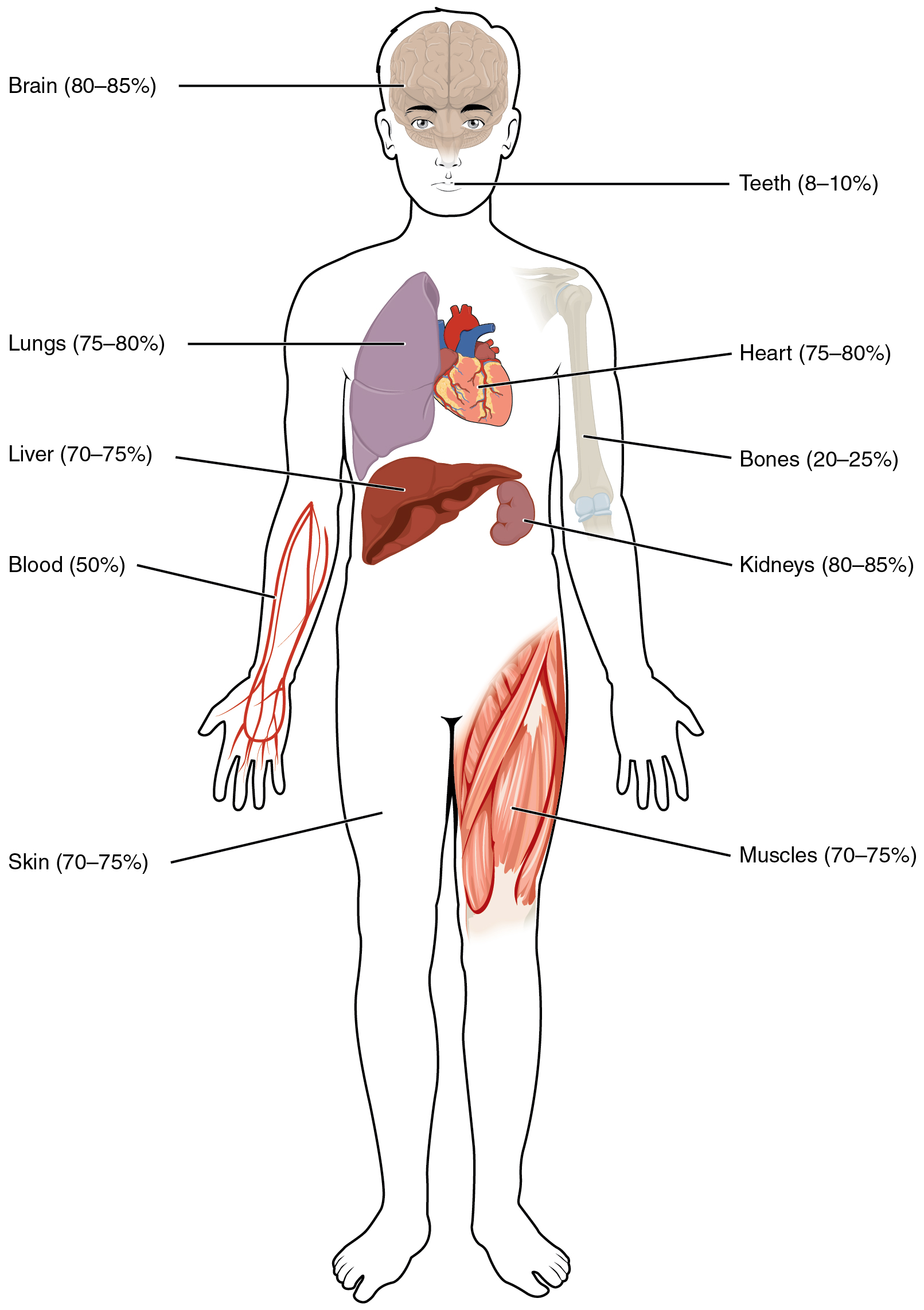

Human beings are mostly water, ranging from about 75 percent of body mass in infants to about 50–60 percent in adult men and women, to as low as 45 percent in old age. The percent of body water changes with development, because the proportions of the body given over to each organ and to muscles, fat, bone, and other tissues change from infancy to adulthood (Figure 77.1). Your brain and kidneys have the highest proportions of water, which composes 80–85 percent of their masses. In contrast, teeth have the lowest proportion of water, at 8–10 percent.

Fluid Compartments

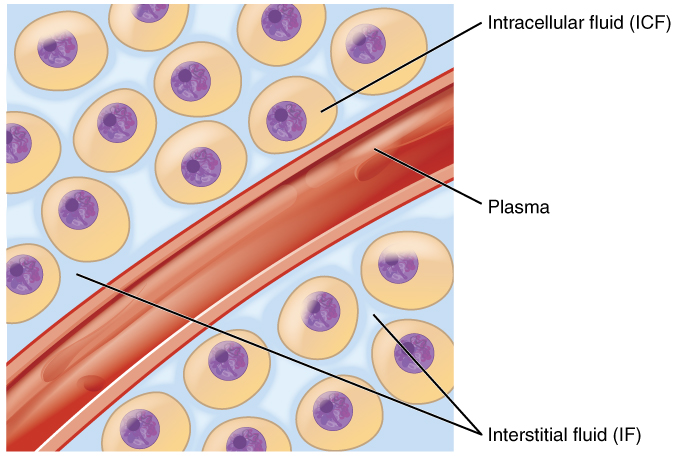

Body fluids can be discussed in terms of their specific fluid compartment, a location that is largely separate from another compartment by some form of a physical barrier. The intracellular fluid (ICF) compartment is the system that includes all fluid enclosed in cells by their plasma membranes. Extracellular fluid (ECF) surrounds all cells in the body. Extracellular fluid has two primary constituents: the fluid component of the blood (called plasma) and the interstitial fluid (IF) that surrounds all cells not in the blood (Figure 77.2).

Intracellular Fluid

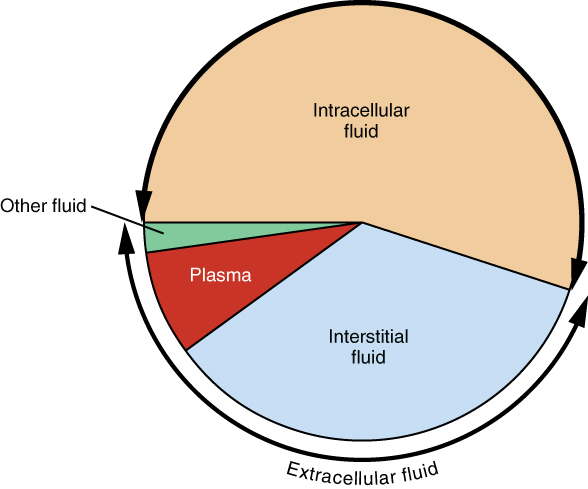

The ICF lies within cells and is the principal component of the cytosol/cytoplasm. The ICF makes up about 60 percent of the total water in the human body, and in an average-size adult male, the ICF accounts for about 25 liters (seven gallons) of fluid (Figure 77.3). This fluid volume tends to be very stable, because the amount of water in living cells is closely regulated. If the amount of water inside a cell falls to a value that is too low, the cytosol becomes too concentrated with solutes to carry on normal cellular activities; if too much water enters a cell, the cell may burst and be destroyed.

Extracellular Fluid

The ECF accounts for the other one-third of the body’s water content. Approximately 20 percent of the ECF is found in plasma. Plasma travels through the body in blood vessels and transports a range of materials, including blood cells, proteins (including clotting factors and antibodies), electrolytes, nutrients, gases, and wastes. Gases, nutrients, and waste materials travel between capillaries and cells through the IF. Cells are separated from the IF by a selectively permeable cell membrane that helps regulate the passage of materials between the IF and the interior of the cell.

The body has other water-based ECF. These include the cerebrospinal fluid that bathes the brain and spinal cord, lymph, the synovial fluid in joints, the pleural fluid in the pleural cavities, the pericardial fluid in the cardiac sac, the peritoneal fluid in the peritoneal cavity, and the aqueous humor of the eye. Because these fluids are outside of cells, these fluids are also considered components of the ECF compartment.

Composition of Body Fluids

The compositions of the two components of the ECF—plasma and IF—are more similar to each other than either is to the ICF. Blood plasma has high concentrations of sodium, chloride, bicarbonate, and protein. The IF has high concentrations of sodium, chloride, calciu, and bicarbonate, but a relatively lower concentration of protein. Because most plasma proteins are too large to cross capillary walls, plasma contains significantly more protein than interstitial fluid.

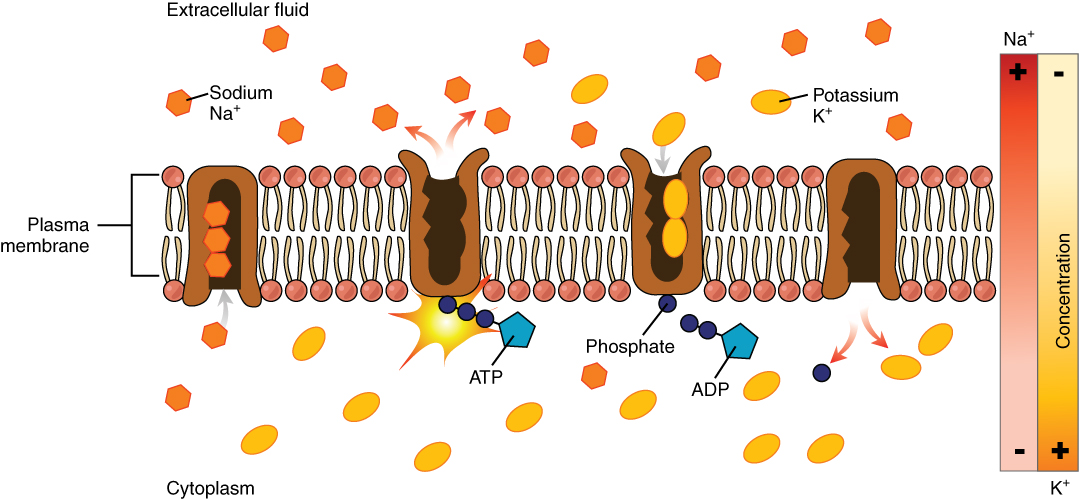

In contrast, the ICF has elevated amounts of potassium, phosphate, magnesium, and protein. Overall, the ICF contains high concentrations of potassium and phosphate (HPO42−), whereas both plasma and the ECF contain high concentrations of sodium and chloride.

Most body fluids are neutral in charge. Thus, cations, or positively charged ions, and anions, or negatively charged ions, are balanced in fluids. As seen in the previous graph, sodium (Na+) ions and chloride (Cl–) ions are concentrated in the ECF of the body, whereas potassium (K+) ions are concentrated inside cells. Although sodium and potassium can “leak” through “pores” into and out of cells, respectively, the high levels of potassium and low levels of sodium in the ICF are maintained by sodium-potassium pumps in the cell membranes. These pumps use the energy supplied by ATP to pump sodium out of the cell and potassium into the cell (Figure 77.4).

Fluid Movement between Compartments

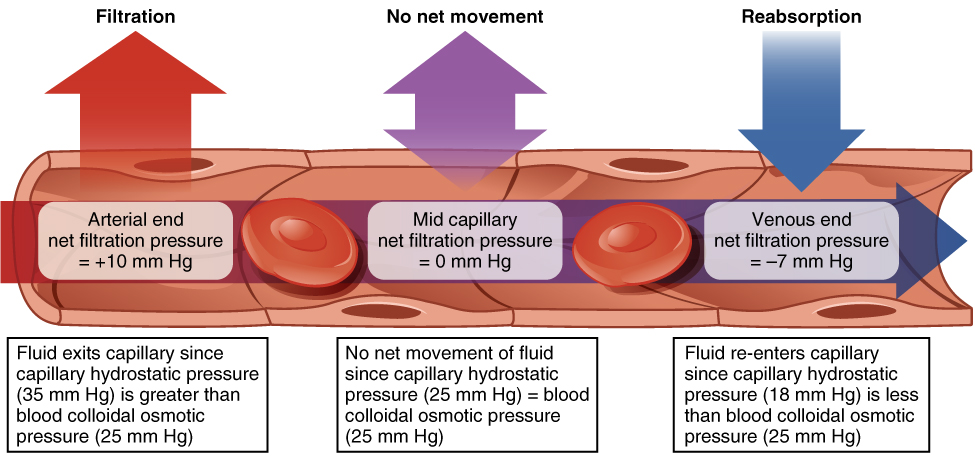

Hydrostatic pressure, the force exerted by a fluid against a wall, causes movement of fluid between compartments. The hydrostatic pressure of blood is the pressure exerted by blood against the walls of the blood vessels by the pumping action of the heart. In capillaries, hydrostatic pressure (also known as capillary blood pressure) is higher than the opposing “colloid osmotic pressure” in blood—a “constant” pressure primarily produced by circulating albumin—at the arteriolar end of the capillary (Figure 77.5). This pressure forces plasma and nutrients out of the capillaries and into surrounding tissues. Fluid and the cellular wastes in the tissues enter the capillaries at the venule end, where the hydrostatic pressure is less than the osmotic pressure in the vessel. Filtration pressure squeezes fluid from the plasma in the blood to the IF surrounding the tissue cells. The surplus fluid in the interstitial space that is not returned directly back to the capillaries is drained from tissues by the lymphatic system, and then re-enters the vascular system at the subclavian veins.

Hydrostatic pressure is especially important in governing the movement of water in the nephrons of the kidneys to ensure proper filtering of the blood to form urine. As hydrostatic pressure in the kidneys increases, the amount of water leaving the capillaries also increases, and more urine filtrate is formed. If hydrostatic pressure in the kidneys drops too low, as can happen in dehydration, the functions of the kidneys will be impaired, and less nitrogenous wastes will be removed from the bloodstream. Extreme dehydration can result in kidney failure.

Fluid also moves between compartments along an osmotic gradient. Recall that an osmotic gradient is produced by the difference in concentration of all solutes on either side of a semi-permeable membrane. The magnitude of the osmotic gradient is proportional to the difference in the concentration of solutes on one side of the cell membrane to that on the other side. Water will move by osmosis from the side where its concentration is high (and the concentration of solute is low) to the side of the membrane where its concentration is low (and the concentration of solute is high). In the body, water moves by osmosis from plasma to the IF (and the reverse) and from the IF to the ICF (and the reverse). In the body, water moves constantly into and out of fluid compartments as conditions change in different parts of the body.

For example, if you are sweating, you will lose water through your skin. Sweating depletes your tissues of water and increases the solute concentration in those tissues. As this happens, water diffuses from your blood into sweat glands and surrounding skin tissues that have become dehydrated because of the osmotic gradient. Additionally, as water leaves the blood, it is replaced by the water in other tissues throughout your body that are not dehydrated. If this continues, dehydration spreads throughout the body. When a dehydrated person drinks water and rehydrates, the water is redistributed by the same gradient, but in the opposite direction, replenishing water in all of the tissues.

Solute Movement between Compartments

The movement of some solutes between compartments is active, which consumes energy and is an active transport process, whereas the movement of other solutes is passive, which does not require energy. Active transport allows cells to move a specific substance against its concentration gradient through a membrane protein, requiring energy in the form of ATP. For example, the sodium-potassium pump employs active transport to pump sodium out of cells and potassium into cells, with both substances moving against their concentration gradients.

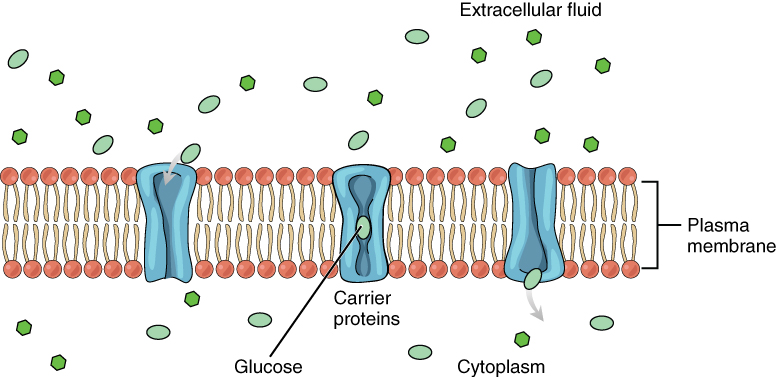

Passive transport of a molecule or ion depends on its ability to pass through the membrane, as well as the existence of a concentration gradient that allows the molecules to diffuse from an area of higher concentration to an area of lower concentration. Some molecules, like gases, lipids, and water itself (which also utilizes water channels in the membrane called aquaporins), slip fairly easily through the cell membrane; others, including polar molecules like glucose, amino acids, and ions do not. Some of these molecules enter and leave cells using facilitated transport, whereby the molecules move down a concentration gradient through specific protein channels in the membrane. This process does not require energy. For example, glucose is transferred into cells by glucose transporters that use facilitated transport (Figure 77.6).

Adapted from Anatomy & Physiology by Lindsay M. Biga et al, shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, chapter 26.