58 Starling forces

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you should be able to-

- Explain the mechanisms of capillary exchange of gases, nutrients, and wastes.

- Describe the forces that create capillary filtration and reabsorption.

- Explain how changes in net filtration pressure (NFP) can result in edema and how a functional lymphatic system normally prevents edema.

The primary purpose of the cardiovascular system is to circulate gases, nutrients, wastes, and other substances to and from the cells of the body. Small molecules, such as gases, lipids, and lipid-soluble molecules, can diffuse directly through the membranes of the endothelial cells of the capillary wall. Glucose, amino acids, and ions—including sodium, potassium, calcium, and chloride—use transporters to move through specific channels in the membrane by facilitated diffusion. Larger molecules can pass through the pores of fenestrated capillaries, and even large plasma proteins can pass through the great gaps in the sinusoids. Some large proteins in blood plasma can move into and out of the endothelial cells packaged within vesicles by endocytosis and exocytosis. Water moves by osmosis.

Bulk Flow

The mass movement of fluids into and out of capillary beds requires a transport mechanism far more efficient than mere diffusion. This movement, often referred to as bulk flow, involves two pressure-driven mechanisms: Volumes of fluid move from an area of higher pressure in a capillary bed to an area of lower pressure in the tissues via filtration. In contrast, the movement of fluid from an area of higher pressure in the tissues into an area of lower pressure in the capillaries is reabsorption. Two types of pressures interact to drive each of these movements: hydrostatic pressure and osmotic pressure.

Hydrostatic Pressure

The primary force driving fluid transport between the capillaries and tissues is hydrostatic pressure, which can be defined as the pressure of any fluid enclosed in a space. Blood hydrostatic pressure is the force exerted by the blood confined within blood vessels or heart chambers. Even more specifically, the pressure exerted by blood against the wall of a capillary is called capillary hydrostatic pressure (CHP), and is the same as capillary blood pressure. CHP is a pushing force that drives fluid out of capillaries and into the tissues.

As fluid exits a capillary and moves into tissues, the hydrostatic pressure in the interstitial fluid correspondingly rises. This opposing hydrostatic pressure is called the interstitial fluid hydrostatic pressure (IFHP). Generally, the CHP originating from the arterial pathways is considerably higher than the IFHP, because lymphatic vessels are continually absorbing excess fluid from the tissues. Thus, fluid generally moves out of the capillary and into the interstitial fluid. This process is called filtration.

Osmotic Pressure

The net pressure that drives reabsorption—the movement of fluid from the interstitial fluid back into the capillaries—is called osmotic pressure. Whereas hydrostatic pressure forces fluid out of the capillary, osmotic pressure draws fluid back in. Osmotic pressure is determined by osmotic concentration gradients, that is, the difference in the solute-to-water concentrations in the blood and tissue fluid. A region higher in solute concentration pulls water across a semipermeable membrane from a region lower in solute concentration.

As we discuss osmotic pressure in blood and tissue fluid, it is important to recognize that the formed elements of blood do not contribute to osmotic concentration gradients. Rather, it is the plasma proteins that play the key role. Solutes also move across the capillary wall according to their concentration gradient, but overall, the concentrations should be similar and not have a significant impact on osmosis. Because of their large size and chemical structure, plasma proteins are not truly solutes; that is, they do not dissolve but are dispersed or suspended in their fluid medium, forming a colloid rather than a solution.

The pressure created by the concentration of colloidal proteins in the blood is called the blood colloidal osmotic pressure (BCOP), also known as capillary oncotic pressure (πcap).Its effect on capillary exchange accounts for the reabsorption of water. The plasma proteins suspended in blood cannot move across the semipermeable capillary cell membrane, and so they remain in the plasma. As a result, blood has a higher colloidal concentration and lower water concentration than tissue fluid. It therefore attracts water. We can also say that the BCOP is higher than the interstitial fluid colloidal osmotic pressure (IFCOP)—also called interstitial oncotic pressure (πif)—which remains very low because interstitial fluid contains few proteins. Thus, water is drawn from the tissue fluid back into the capillary, carrying dissolved molecules with it. This difference in colloidal osmotic pressure accounts for reabsorption.

Interaction of Hydrostatic and Osmotic Pressures

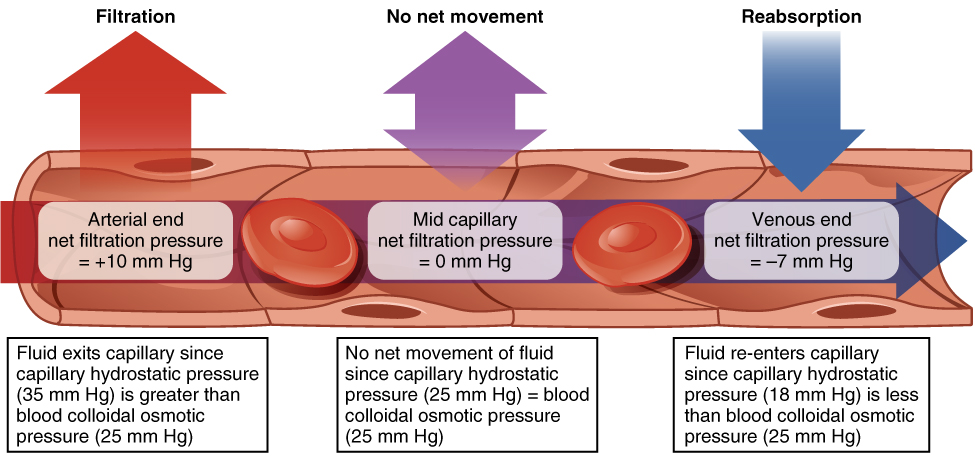

The normal unit used to express pressures within the cardiovascular system is millimeters of mercury (mm Hg). When blood leaving an arteriole first enters a capillary bed, the CHP is quite high—about 35 mm Hg. Gradually, this initial CHP declines as the blood moves through the capillary so that by the time the blood has reached the venous end, the CHP has dropped to approximately 18 mm Hg. In comparison, the plasma proteins remain suspended in the blood, so the BCOP remains fairly constant at about 25 mm Hg throughout the length of the capillary and considerably below the osmotic pressure in the interstitial fluid.

The net filtration pressure (NFP) represents the interaction of the hydrostatic and osmotic pressures, driving fluid out of the capillary. It is equal to the difference between the CHP and the BCOP. Since filtration is, by definition, the movement of fluid out of the capillary, when reabsorption is occurring, the NFP is a negative number.

Starling equation (with π/P notation):

NFP = (Pcap+ πif) – (Pif + πcap) where:

-

Pcap = capillary hydrostatic pressure (CHP)

-

Pif = interstitial fluid hydrostatic pressure (IFHP)

-

πcap = capillary oncotic pressure (BCOP)

-

πif = interstitial oncotic pressure (IFCOP)

Note: πif and Pif are normally very small (≈0 mm Hg) in healthy tissues.

NFP changes at different points in a capillary bed (Figure 57.1). Close to the arterial end of the capillary, it is approximately 10 mm Hg, because the CHP of 35 mm Hg minus the BCOP of 25 mm Hg equals 10 mm Hg. Recall that the hydrostatic and osmotic pressures of the interstitial fluid are essentially negligible. Thus, the NFP of 10 mm Hg drives a net movement of fluid out of the capillary at the arterial end. At approximately the middle of the capillary, the CHP is about the same as the BCOP of 25 mm Hg, so the NFP drops to zero. At this point, there is no net change of volume: Fluid moves out of the capillary at the same rate as it moves into the capillary. Near the venous end of the capillary, the CHP has dwindled to about 18 mm Hg due to loss of fluid. Because the BCOP remains steady at 25 mm Hg, water is drawn into the capillary and reabsorption occurs. At the venous end of the capillary, there is an NFP of −7 mm Hg.

At the arterial end of a capillary bed:

-

Pcap = 35 mm Hg

-

πif ≈ 0 mm Hg

-

Pif ≈ 0 mm Hg

-

πcap = 25 mm Hg

Therefore, NFP = (35 + 0) – (0 + 25) = +10 mm Hg. A positive NFP means net filtration (fluid moves out of the capillary).

Edema and the Lymphatic System

Edema occurs when excess fluid accumulates in tissues, which can result from an increase in CHP or a decrease in BCOP, leading to a higher NFP and more fluid leaving the capillaries than being reabsorbed. A functional lymphatic system normally prevents edema by absorbing excess interstitial fluid and returning it to the bloodstream. When the lymphatic system is compromised, fluid can accumulate in the tissues, leading to edema.

Adapted from Anatomy & Physiology by Lindsay M. Biga et al, shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, chapter 20

movement of substances from areas of high to low concentration

a form of passive transport in which ions are moved across the membrane with protein interaction

net movement of water across a semi-permeable from an area where it is higher in volume to an area where it is lower in volume; the movement of water down its concentration gradient

the movement of fluid from an area of high pressure in a capillary bed to an area of low pressure in the tissues

the movement of fluid from an area of high pressure in the tissues to an area of low pressure in the capillaries

the force exerted by the blood confined within blood vessels or heart chambers

the pressure exerted by blood against the wall of a capillary; a pushing force driving fluid out of the capillaries and into the tissues

a sub-compartment of extracellular fluid that bathes cells and provides a medium of exchange for substances between the blood and cells

opposing capillary hydrostatic pressure, created by fluid against the walls of the tissues; a pushing force driving fluid out of the tissue and into the capillary

the pressure created by the concentration of colloidal proteins in the blood

the pressure created by the concentration of colloidal proteins in the interstitial fluid

the difference between capillary hydrostatic pressure and blood colloidal osmotic pressure; the force driving fluid out of the capillary