94 Digestive structure and functions

Learning Objectives

After reading this section you should be able to-

-

Describe the major functions of the digestive system.

-

Explain the differences between the gastrointestinal (GI) tract (alimentary canal) and the accessory digestive organs.

-

Compare and contrast mechanical digestion and chemical digestion, including where they occur in the digestive system.

-

Define peristalsis.

-

Trace the pathway of ingested substances through the gastrointestinal (GI) tract.

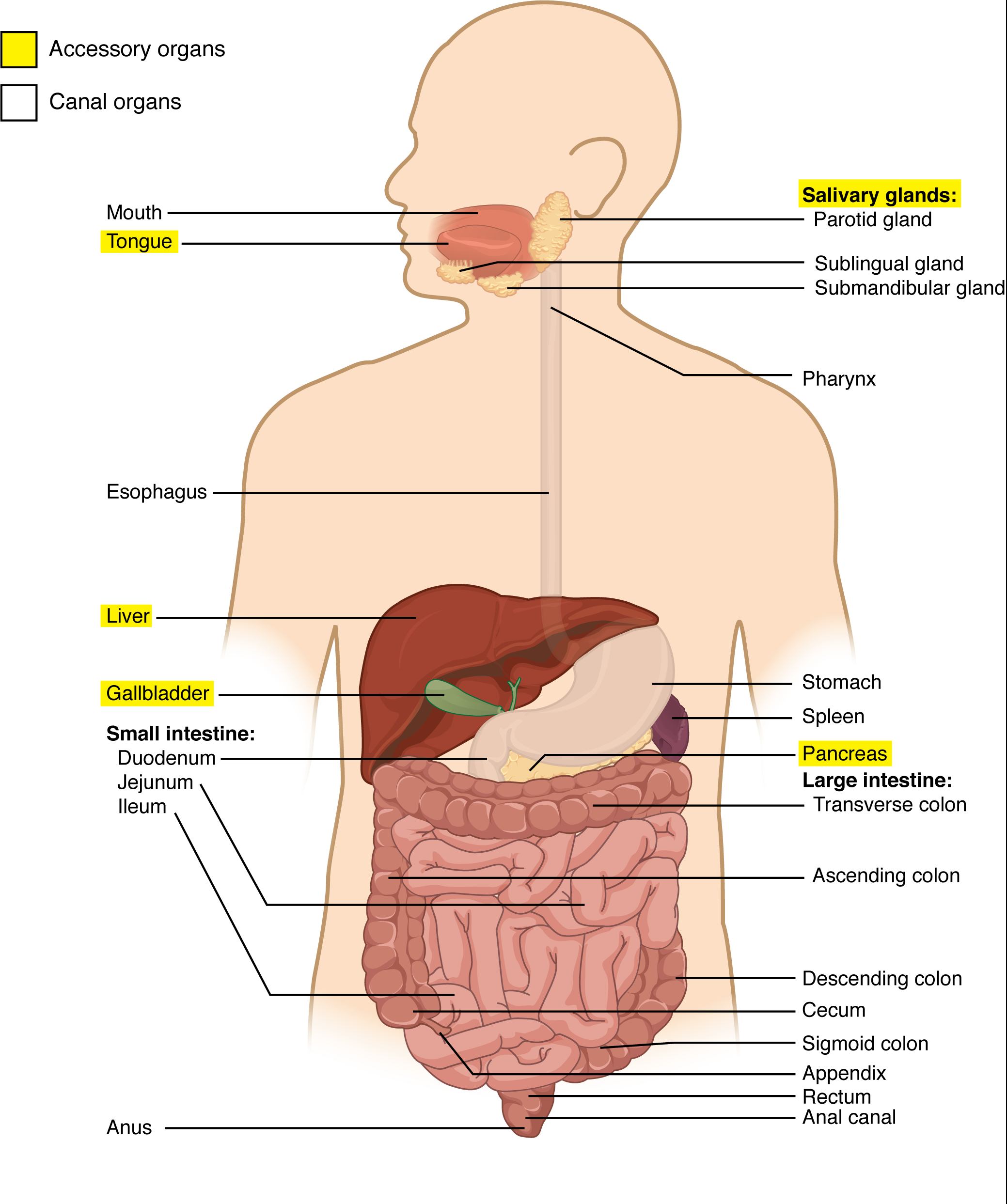

The function of the digestive system is to break down the foods you eat, release their nutrients, and absorb those nutrients into the body. Although the small intestine is the workhorse of the system, where the majority of digestion occurs, and where most of the released nutrients are absorbed into the blood or lymph, each of the digestive system organs makes a vital contribution to this process (Figure 93.1).

Digestive System Organs

The easiest way to understand the digestive system is to divide its organs into two main categories. The first group is the organs that make up the alimentary canal. Accessory digestive organs comprise the second group and are critical for orchestrating the breakdown of food and the assimilation of its nutrients into the body. Accessory digestive organs, despite their name, are critical to the function of the digestive system.

Alimentary Canal Organs

Also called the gastrointestinal (GI) tract or gut, the alimentary canal (aliment- = “to nourish”) is a one-way tube about 7.62 meters (25 feet) in length during life and closer to 10.67 meters (35 feet) in length when measured after death, once smooth muscle tone is lost. The main function of the organs of the alimentary canal is to nourish the body by digesting food and absorbing released nutrients. This tube begins at the mouth and terminates at the anus. Between those two points, the canal is modified as the pharynx, esophagus, stomach, and small and large intestines to fit the functional needs of the body. Both the mouth and anus are open to the external environment; thus, food and wastes within the alimentary canal are technically considered to be outside the body. Only through the process of absorption do the nutrients in food enter into and nourish the body’s “inner space.”

Accessory Structures

Accessory structures within the digestive system play vital roles in facilitating the breakdown of food and the absorption of nutrients. These structures include the following:

- Teeth and Tongue: Primarily involved in mechanical digestion, teeth chew and grind food into smaller pieces, while the tongue helps manipulate food for swallowing.

- Salivary Glands: These glands secrete saliva containing enzymes like amylase, which initiate the breakdown of carbohydrates in the mouth.

- Gallbladder: Serving as a storage reservoir for bile produced by the liver, the gallbladder releases bile into the small intestine to aid in the emulsification and digestion of fats.

- Liver: Producing bile, the liver plays a crucial role in fat digestion and assists in the metabolism of nutrients absorbed by the digestive system.

- Pancreas: The pancreas secretes digestive enzymes (such as lipase, protease, and amylase) into the small intestine to further break down fats, proteins, and carbohydrates.

These accessory organs significantly contribute to the digestive process, enhancing the efficiency of nutrient breakdown and absorption.

Digestive Processes

While the digestive system’s overarching goals can be summarized as breaking down food, absorbing nutrients, and excreting waste, these goals are achieved through six coordinated processes: ingestion, propulsion, mechanical digestion, chemical digestion, absorption, and defecation. Each of these steps contributes to the system’s primary functions and will be discussed in detail below.

The processes of digestion include six activities: ingestion, propulsion, mechanical or physical digestion, chemical digestion, absorption, and defecation.

The first of these processes, ingestion, refers to the entry of food into the alimentary canal through the mouth. There, the food is chewed and mixed with saliva, which contains enzymes that begin breaking down the carbohydrates in the food plus some lipid digestion via lingual lipase. Chewing increases the surface area of the food and allows an appropriately sized bolus to be produced.

Food leaves the mouth when the tongue and pharyngeal muscles propel it into the esophagus. This act of swallowing, the last voluntary act until defecation, is an example of propulsion, which refers to the movement of food through the digestive tract. It includes both the voluntary process of swallowing and the involuntary process of peristalsis. Peristalsis consists of sequential, alternating waves of contraction and relaxation of alimentary wall smooth muscles, which act to propel food along. These waves also play a role in mixing food with digestive juices. Peristalsis is so powerful that foods and liquids you swallow enter your stomach even if you are standing on your head.

Digestion includes both mechanical and chemical processes. Mechanical digestion is a purely physical process that does not change the chemical nature of the food. Instead, it makes the food smaller to increase both surface area and mobility. It includes mastication, or chewing, as well as tongue movements that help break food into smaller bits and mix food with saliva. Although there may be a tendency to think that mechanical digestion is limited to the first steps of the digestive process, it occurs after the food leaves the mouth as well. The mechanical churning of food in the stomach serves to further break it apart and expose more of its surface area to digestive juices, creating an acidic “soup” called chyme. Segmentation, which occurs mainly in the small intestine, consists of localized contractions of circular muscle of the muscularis layer of the alimentary canal. These contractions isolate small sections of the intestine, moving their contents back and forth while continuously subdividing, breaking up, and mixing the contents. By moving food back and forth in the intestinal lumen, segmentation mixes food with digestive juices and facilitates absorption.

In chemical digestion, starting in the mouth, digestive secretions break down complex food molecules into their chemical building blocks (for example, proteins into separate amino acids). These secretions vary in composition, but typically contain water, various enzymes, acids, and salts. The process is completed in the small intestine.

Adapted from Anatomy & Physiology by Lindsay M. Biga et al, shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, chapter 23.

gastrointestinal (GI) tract; passageway along which food passes through the digestive system, from mouth to anus; includes the pharynx, esophagus, stomach, and intestines

entry of food or drink into the alimentary canal through the mouth

movement of food through the digestive tract, including swallowing and peristalsis

sequential, alternating waves of contraction and relaxation of alimentary smooth muscles that push food along the gastrointestinal tract

physical breakdown of food substances into smaller particles without changing the chemical nature of the food

chewing, a form of mechanical digestion

thick, acidic semifluid mass created by partly digested food mixing with digestive juices in the stomach which is propelled to the duodenum

process occurring in the small intestine during which circular smooth muscle of the muscularis layer contracts to break up and mix digestive contents with digestive juices and facilitate absorption

process utilizing enzymes to break down food into smaller molecules that can be absorbed