89 Uterine cycle

Learning Objectives

After reading this section, you should be able to-

- Name the phases of the uterine (menstrual) cycle, and describe the anatomical changes in the uterine wall that occur during each phase.

- Describe the correlation between the uterine and ovarian cycles.

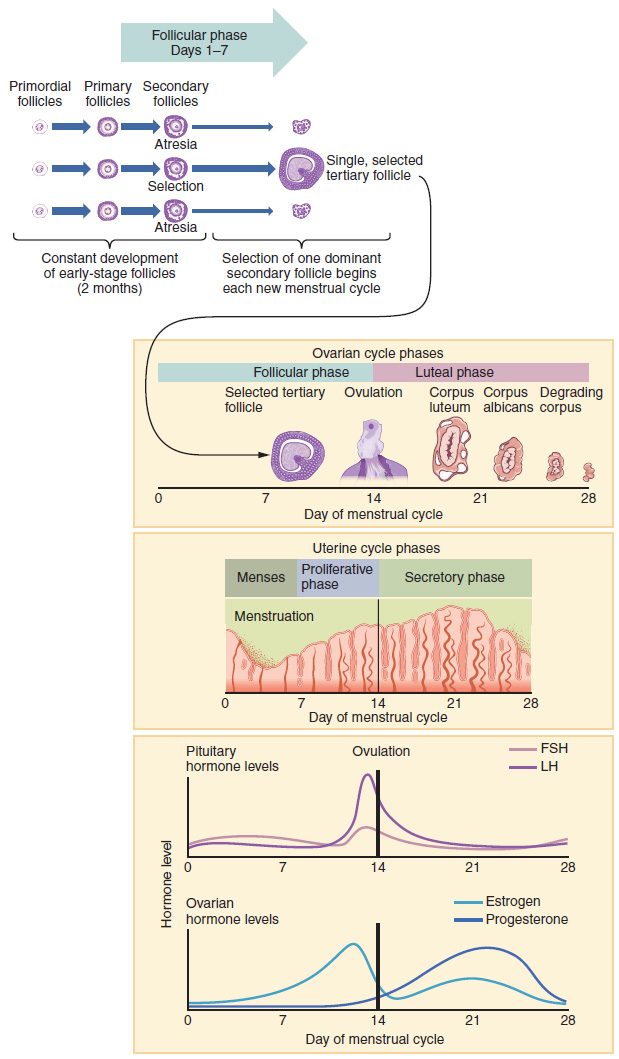

Now that we have discussed the maturation of the cohort of tertiary follicles in the ovary, the build-up of the endometrial lining in the uterus, and the function of the uterine tubes and vagina, we can put everything together to talk about the three phases of the uterine cycle—the series of changes in which the uterine lining is shed, rebuilds, and prepares for implantation.

The timing of the uterine cycle starts with the first day of menses, referred to as day one of a woman’s period. Cycle length is determined by counting the days between the onset of bleeding in two subsequent cycles. Because the average length of a woman’s uterine cycle is 28 days, this is the time period used to identify the timing of events in the cycle. However, the length of the uterine cycle varies among women, and even in the same woman from one cycle to the next, typically from 21 to 32 days.

Just as the hormones produced by the granulosa and theca cells of the ovary “drive” the follicular and luteal phases of the ovarian cycle, they also control the three distinct phases of the uterine cycle. These are the menstrual phase, the proliferative phase, and the secretory phase.

Menstrual Phase

The menstrual phase of the uterine cycle is the phase during which the uterine lining is shed; that is, the days that the woman menstruates. Although it averages approximately five days, the menstrual phase can last from 2 to 7 days, or longer. As shown in Figure 88.1, the menstrual phase occurs during the early days of the follicular phase of the ovarian cycle, when progesterone, FSH, and LH levels are low. Recall that progesterone concentrations decline as a result of the degradation of the corpus luteum, marking the end of the luteal phase. This decline in progesterone triggers the shedding of the stratum functionalis of the endometrium. Endometrial cells also release prostaglandins, which constrict spiral arteries and help drive the cramping pain that often accompanies menstruation

Proliferative Phase

Once menstrual flow ceases, the endometrium begins to proliferate again, marking the beginning of the proliferative phase of the uterine cycle (see Figure 88.1). It occurs when the granulosa and theca cells of the tertiary follicles begin to produce increased amounts of estrogen. These rising estrogen concentrations stimulate the endometrial lining to rebuild.

Recall that the high estrogen concentrations will eventually lead to a decrease in FSH as a result of negative feedback, resulting in atresia of all but one of the developing tertiary follicles. The switch to positive feedback—which occurs with the elevated estrogen production from the dominant follicle—then stimulates the LH surge that will trigger ovulation. In a typical 28-day uterine cycle, ovulation occurs on day 14. Ovulation marks the end of the proliferative phase as well as the end of the follicular phase.

Secretory Phase

In addition to prompting the LH surge, high estrogen levels increase the uterine tube contractions that facilitate the pick-up and transfer of the ovulated oocyte. High estrogen levels also slightly decrease the acidity of the vagina, making it more hospitable to sperm. In the ovary, the luteinization of the granulosa cells of the collapsed follicle forms the progesterone-producing corpus luteum, marking the beginning of the luteal phase of the ovarian cycle. In the uterus, progesterone from the corpus luteum begins the secretory phase of the uterine cycle, in which the endometrial lining prepares for implantation (Figure 87.1). Over the next 10 to 12 days, the endometrial glands secrete a fluid rich in glycogen. If fertilization has occurred, this fluid will nourish the ball of cells now developing from the zygote. At the same time, the spiral arteries develop to provide blood to the thickened stratum functionalis.

If no pregnancy occurs within approximately 10 to 12 days, the corpus luteum will degrade into the corpus albicans. Levels of both estrogen and progesterone will fall, and the endometrium will grow thinner. Prostaglandins will be secreted that cause constriction of the spiral arteries, reducing oxygen supply. The endometrial tissue will die, resulting in menses—or the first day of the next uterine cycle.

Correlation Between Uterine and Ovarian Cycles

The ovarian and uterine cycles are closely linked, with the hormones produced by the ovary driving the changes in the uterine lining. The ovarian cycle consists of the follicular phase, ovulation, and the luteal phase. These stages correspond with the menstrual phase, proliferative phase, and secretory phase of the uterine cycle, respectively.

Hormonal Interactions in the Menstrual Cycle

The menstrual cycle is a finely orchestrated dance of hormones that involves intricate interactions between the hypothalamus, pituitary gland, and ovaries. As we delve deeper into the phases of this cycle, it’s crucial to appreciate the dynamic hormonal regulation governing each stage.

During the Menstrual Phase

The initiation of the menstrual cycle is marked by the shedding of the endometrial lining, known as the menses phase. This occurs in response to a decline in progesterone levels, triggered by the degradation of the corpus luteum. The low concentrations of progesterone, along with reduced levels of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH), create an environment conducive to the detachment of the stratum functionalis.

Transitioning to the Proliferative Phase

Following the menses phase, the body enters the proliferative phase, characterized by the resurgence of endometrial growth. This regeneration is propelled by increasing estrogen levels produced by the developing tertiary follicles. Notably, the rising estrogen concentrations set off a delicate hormonal feedback loop. Initially suppressing FSH through negative feedback, estrogen then triggers a switch to positive feedback, culminating in the LH surge responsible for ovulation.

Embarking on the Secretory Phase

As ovulation concludes the proliferative phase, the menstrual cycle progresses into the secretory phase. High levels of estrogen persist, stimulating uterine tube contractions and creating a sperm-friendly vaginal environment. Simultaneously, in the ovary, luteinization transforms the collapsed follicle into the progesterone-secreting corpus luteum. This marks the onset of the luteal phase of the ovarian cycle and the secretory phase of the menstrual cycle. Progesterone orchestrates the preparation of the endometrium for potential implantation, promoting the secretion of nourishing fluids and the development of spiral arteries.

Understanding these intricate hormonal dynamics is pivotal to grasp the nuanced interplay between the ovarian and menstrual cycles. As we navigate through these phases, keep in mind the exquisite regulatory mechanisms that ensure the uterus is primed for both fertilization and the cyclical renewal of its lining.

Adapted from Anatomy & Physiology by Lindsay M. Biga et al, shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, chapter 27.

large follicles containing a secondary oocyte that have a fully formed antrum and multiple layers of granulosa cells

the series of changes in which the uterine lining is shed, rebuilds, and prepares for implantation

the phase of the uterine cycle during which the inner lining (endometrium) of the uterus is shed due to the absence of implantation

the mass of cells that forms in the ovary, responsible for the production of progesterone and thickening of the uterine lining, following ovulation

the phase of the uterine cycle following menstruation, during which increased levels of estrogen cause the endometrial lining to rebuild

the release of an oocyte from the ovary

the phase of the uterine cycle during which progesterone is secreted by the corpus luteum and endometrial glands secrete glycogen-rich fluid, resulting in the preparation of the uterine lining for implantation

white scar tissue resulting from the degeneration of the corpus luteum in the absence of fertilization and implantation