2 Derivatives

The derivative function ![]() of

of ![]() gives us the rate at which the dependent variable

gives us the rate at which the dependent variable ![]() is changing in relation to the independent variable

is changing in relation to the independent variable ![]() . Because the slope is the rate at which the dependent variable is changing in relation to the independent variable, the derivative can be thought of as slope. In fact, the derivative of a function

. Because the slope is the rate at which the dependent variable is changing in relation to the independent variable, the derivative can be thought of as slope. In fact, the derivative of a function ![]() at a point

at a point ![]() is the slope of the tangent line at

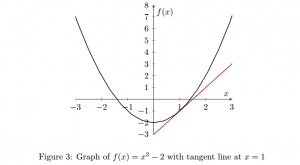

is the slope of the tangent line at ![]() . Consider the following function.

. Consider the following function.

What we want to do is find the slope of the tangent line at ![]() in order to determine the slope of

in order to determine the slope of ![]() at

at ![]() . We know that the slope of the line between two points is given as

. We know that the slope of the line between two points is given as

![]()

Let ![]() and

and ![]() . Now we have

. Now we have

![]()

The problem is that this gives the slope of a secant line of ![]() . So, how do we get the slope of the tangent line? We are going to approximate it with the slope of the secant line that is as close to being the tangent line as possible. We find this secant line by choosing

. So, how do we get the slope of the tangent line? We are going to approximate it with the slope of the secant line that is as close to being the tangent line as possible. We find this secant line by choosing ![]() to be as close to 0 as possible without

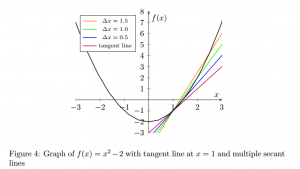

to be as close to 0 as possible without ![]() equaling 0. Consider the following graph.

equaling 0. Consider the following graph.

As ![]() gets closer to 0, the secant lines get closer to the tangent (purple) line. So, to find the slope of the tangent line, we need to find

gets closer to 0, the secant lines get closer to the tangent (purple) line. So, to find the slope of the tangent line, we need to find

![]()

Generalizing this result, we have the formal definition from Larson and Edwards [15].

The derivative of

![]()

provided the limit exists. For all ![]() for which this limit exists,

for which this limit exists, ![]() is a function of

is a function of ![]() .

.

Additionally, the process of finding the derivative is known as differentiation, and the derivative of ![]() with respect to

with respect to ![]() is denoted as

is denoted as

![]()

It is possible to use Definition I.3 to find derivatives by substituting ![]() in and taking the limit as

in and taking the limit as ![]() approaches 0. However, this process can become quite long and prone to error when dealing with complicated functions. In fact, finding derivatives using the definition is rarely used. Instead, the definition is used to prove derivative rules that make finding derivatives simpler and easier. Consider the following rules from Larson and Edwards [15].

approaches 0. However, this process can become quite long and prone to error when dealing with complicated functions. In fact, finding derivatives using the definition is rarely used. Instead, the definition is used to prove derivative rules that make finding derivatives simpler and easier. Consider the following rules from Larson and Edwards [15].

- The Constant Rule:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \displaystyle\frac{d}{dx}[c]=0](https://iu.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/quicklatex/quicklatex.com-cf183e838a5b9b9b687a853665bc151f_l3.png) where

where  is a real number

is a real number - The Power Rule:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \displaystyle\frac{d}{dx}[x^n]=nx^{n-1}](https://iu.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/quicklatex/quicklatex.com-702c5917d6c5ee9928ce94320db1a2ba_l3.png) where

where  is a rational number

is a rational number - The Constant Multiple Rule:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \displaystyle\frac{d}{dx}[cf(x)]=cf'(x)](https://iu.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/quicklatex/quicklatex.com-c29179addeacbe7787214092113867bd_l3.png) where

where  is a real number

is a real number - The Sum and Difference Rules:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \displaystyle\frac{d}{dx}[f(x)\pm g(x)]=f'(x)\pm g'(x)](https://iu.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/quicklatex/quicklatex.com-4cec9b8b43f1b51ac30f52a2e7cc8841_l3.png)

Each of these rules can be proven by substituting into the formula given in the definition of a derivative, rewriting and simplifying, and then taking the limit. In the following pages, this will be demonstrated using the proofs for the product rule and quotient rule.

Let’s now put the above differentiation rules into practice by going through a problem I completed for Calculus I that comes from Larson and Edwards [15].

Find the derivative of

Solution

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \begin{align*} \frac{d}{dx}[f(x)]&=\frac{d}{dx}[x^2+5-3x^{-2}]\\ &=\frac{d}{dx}[x^2]+\frac{d}{dx}[5]-\frac{d}{dx}[3x^{-2}] &&\text{Sum and Difference Rules}\\ &=\frac{d}{dx}[x^2]+\frac{d}{dx}[5]-3\left(\frac{d}{dx}[x^{-2}]\right) &&\text{Constant Multiple Rule}\\ &=2x+6x^{-3} &&\text{Constant and Power Rules}\\ \end{align*}](https://iu.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/quicklatex/quicklatex.com-f74ce9db718729800afa15d24e815439_l3.png)

Differentiating products and quotients is more complicated so we will look at the product and quotient rules separately, providing an example for each.

Product Rule

The following definition and proof of the product rule are from Larson and Edwards [15].

Theorem I.4

![]()

Proof.

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \begin{align*} \frac{d}{dx}[f(x)g(x)]&=\lim_{\Delta x\rightarrow 0}\frac{f(x+\Delta x)g(x+\Delta x)-f(x)g(x)}{\Delta x}\\ \text{}\\ &=\lim_{\Delta x\rightarrow 0}\frac{f(x+\Delta x)g(x+\Delta x)-f(x+\Delta x)g(x)}{\Delta x}\;+\\ &\,\quad\lim_{\Delta x\rightarrow 0}\frac{f(x+\Delta x)g(x)-f(x)g(x)}{\Delta x} \\ \text{}\\ &=\lim_{\Delta x\rightarrow 0}f(x+\Delta x)\frac{g(x+\Delta x)-g(x)}{\Delta x}\;+\\ &\,\quad\lim_{\Delta x\rightarrow 0}g(x)\frac{f(x+\Delta x)-f(x)}{\Delta x}\\ \text{}\\ &=\lim_{\Delta x\rightarrow 0}f(x+\Delta x)\cdot \lim_{\Delta x\rightarrow 0}\frac{g(x+\Delta x)-g(x)}{\Delta x}\;+\\ &\,\quad\lim_{\Delta x\rightarrow 0}g(x)\cdot \lim_{\Delta x\rightarrow 0}\frac{f(x+\Delta x)-f(x)}{\Delta x}\\ \text{}\\ &=f(x)g'(x)+g(x)f'(x) \end{align*}](https://iu.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/quicklatex/quicklatex.com-8da7e5d3a154ee33d7c417df6d22c457_l3.png)

Now, let’s practice using a problem I completed for Calculus I that comes from Larson and Edwards [15].

Find the derivative of

Solution

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \begin{align*} \frac{d}{dx}[f(x)]&=\frac{d}{dx}[(x^2+3)(x^2-4x)]\\ &=(x^2+3)\left(\frac{d}{dx}[x^2-4x]\right)+(x^2-4x)\left(\frac{d}{dx}[x^2+3]\right) \\ &=(x^2+3)(2x-4)+(x^2-4x)(2x)\\ &=2x^3-4x^2+6x-12+2x^3-8x^2\\ &=4x^3-12x^2+6x-12 \end{align*}](https://iu.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/quicklatex/quicklatex.com-7d2885c890d3238f8ee3b0f66d5ae790_l3.png)

Therefore, the derivative function of ![]() is

is

![]()

Interpreting this result, the slope of ![]() at

at ![]() is

is ![]() . Equivalently, the rate at which

. Equivalently, the rate at which ![]() is changing at

is changing at ![]() is

is ![]() .

.

Quotient Rule

The following definition and proof of the quotient rule are from Larson and Edwards as well [15].

Theorem I.5

![]()

Proof.

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \begin{align*} \frac{d}{dx}\left[\frac{f(x)}{g(x)}\right]&=\lim_{\Delta x\rightarrow 0}\frac{\displaystyle\left[\frac{f(x+\Delta x)}{g(x+\Delta x)}-\displaystyle\frac{f(x)}{g(x)}\right]}{\Delta x}\\ \text{}\\ &=\lim_{\Delta x\rightarrow 0}\frac{g(x)f(x+\Delta x)-f(x)g(x+\Delta x)}{\Delta x\cdot g(x)\cdot g(x+\Delta x)}\\ \text{}\\ &=\lim_{\Delta x\rightarrow 0}\frac{g(x)f(x+\Delta x)-f(x)g(x)+f(x)g(x)-f(x)g(x+\Delta x)}{\Delta x\cdot g(x)\cdot g(x+\Delta x)}\\ \text{}\\ &=\displaystyle\lim_{\Delta x\rightarrow 0}\displaystyle\frac{\left[\displaystyle\frac{g(x)[f(x+\Delta x)-f(x)]-f(x)[g(x+\Delta x)-g(x)]}{\Delta x}\right]}{g(x)\cdot g(x+\Delta x)}\\ \text{}\\ &=\frac{\displaystyle\lim_{\Delta x\rightarrow 0}\frac{g(x)[f(x+\Delta x)-f(x)]}{\Delta x}-\displaystyle\lim_{\Delta x\rightarrow 0}\frac{f(x)[g(x+\Delta x)-g(x)]}{\Delta x}}{\displaystyle\lim_{\Delta x\rightarrow 0}(g(x)\cdot g(x+\Delta x))}\\ \text{}\\ &=\frac{g(x)\left[\displaystyle\lim_{\Delta x\rightarrow 0}\frac{f(x+\Delta x)-f(x)}{\Delta x}\right]-f(x)\left[\displaystyle\lim_{\Delta x\rightarrow 0}\frac{g(x+\Delta x)-g(x)}{\Delta x}\right]}{\displaystyle\lim_{\Delta x\rightarrow 0}(g(x)\cdot g(x+\Delta x))}\\ \text{}\\ &=\frac{g(x)f'(x)-f(x)g'(x)}{[g(x)]^2} \end{align*}](https://iu.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/quicklatex/quicklatex.com-262f1648f7fedca5a1567150d0ec38a0_l3.png)

Let’s now practice using a problem I completed for Calculus I that comes from Larson and Edwards [15].

Find the derivative of

Solution

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \begin{align*} \frac{d}{dx}[f(x)]&=\frac{d}{dx}\left[\frac{x}{x^2+1}\right]\\ &=\frac{(x^2+1)\frac{d}{dx}[x]-(x)\frac{d}{dx}[x^2+1]}{(x^2+1)^2} &&\text{Quotient Rule}\\ &=\frac{(x^2+1)(1)-(x)(2x)}{(x^2+1)^2}\\ &=\frac{x^2+1-2x^2}{(x^2+1)^2}\\ &=\frac{-x^2+1}{(x^2+1)^2}\\ \end{align*}](https://iu.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/quicklatex/quicklatex.com-7754e36d4fd8ffab02cc440b2ee74b96_l3.png)

Therefore, the derivative function of ![]() is

is

![]()

The next rule we will discuss is the chain rule which enables us to differentiate functions within functions.

Chain Rule

Consider the function ![]() How would we differentiate this? From the power rule, it would seem that

How would we differentiate this? From the power rule, it would seem that

![]()

But is this actually correct? Let us expand ![]() to get

to get ![]() In this case,

In this case,

![]()

We cannot simply use the power rule because we do not have ![]() raised to a power but rather a function of

raised to a power but rather a function of ![]() raised to a power. We can think of

raised to a power. We can think of ![]() as being

as being ![]() where

where ![]() . When we only used the power rule, we did not differentiate

. When we only used the power rule, we did not differentiate ![]() with respect to

with respect to ![]() but rather with respect to

but rather with respect to ![]() . So, how do we get from

. So, how do we get from ![]() to

to ![]() ? The solution to this problem is the chain rule, which is stated by Larson and Edwards as follows [15].

? The solution to this problem is the chain rule, which is stated by Larson and Edwards as follows [15].

Theorem I.6

![]()

or, equivalently,

![]()

In other words, the solution is to multiply ![]() by

by ![]() . The theorem states it as

. The theorem states it as

![]()

because ![]() cancels. So, going back to our example, what is

cancels. So, going back to our example, what is ![]() when

when

![]()

We have ![]() and

and ![]() . By the chain rule,

. By the chain rule,

![]()

Let’s now put the chain rule into practice with a more complicated function. This is a problem I completed for Calculus I and comes from Larson and Edwards [15].

Find the derivative of

Solution

Let ![]() and

and ![]()

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \begin{align*} \frac{d}{dx}f(x)&=\frac{d}{dx}(h(g(x))\\ &=h'g(x)\cdot g'(x) &&\text{Chain Rule}\\ &=\frac{1}{3}(g(x))^{-\frac{2}{3}}\cdot (12x) \\ &=\frac{4x}{\sqrt[3]{(g(x))^2}}\\ &=\frac{4x}{\sqrt[3]{(6x^2+1)^2}}\\ \end{align*}](https://iu.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/quicklatex/quicklatex.com-a099303be7ad9c165e00555d0ef58d7e_l3.png)

Before moving on to integrals, we are going to discuss a special type of differentiation, known as implicit differentiation. As the name suggests, implicit differentiation is the process we use to differentiate implicit functions.

Implicit Differentiation

There are two forms that a function can take, implicit and explicit. An explicit function is one where one variable is clearly a function of another variable or variables. This type of function is what we have been dealing with so far. For example,

![]()

is an explicit function because ![]() is clearly a function of

is clearly a function of ![]() . On the other hand,

. On the other hand,

![]()

is an implicit function because it is not clear whether ![]() is a function of

is a function of ![]() or vice versa.

or vice versa.

For this particular equation, we restrict both ![]() and

and ![]() to be greater than or equal to 0 because this equation may not be a function otherwise. If

to be greater than or equal to 0 because this equation may not be a function otherwise. If ![]() is a function of

is a function of ![]() , we can solve for

, we can solve for ![]() to get

to get

![]()

Because the square root can be positive or negative, we have

![]()

This is not a function because ![]() . Thus, we must restrict

. Thus, we must restrict ![]() to being nonnegative so that it is a function. This works in a similar manner for if

to being nonnegative so that it is a function. This works in a similar manner for if ![]() is a function of

is a function of ![]() . Because we do not know whether

. Because we do not know whether ![]() is a function of

is a function of ![]() or vice versa, we must restrict both

or vice versa, we must restrict both ![]() and

and ![]() to being nonnegative so that we are guaranteed

to being nonnegative so that we are guaranteed ![]() is an implicit function. For a more detailed discussion of functions, see Part III: Chapter 15.

is an implicit function. For a more detailed discussion of functions, see Part III: Chapter 15.

Sometimes, the implicit form does not cause too much trouble when differentiating. This is when we can easily solve for either one of the variables to be in terms of the other variable. Then, we can differentiate like normal. However, it is not always easy to solve for a variable. Take, for example,

![]()

It is not clear how one might solve for ![]() in order to find

in order to find ![]() . This is where the process of implicit differentiation comes in. The steps of implicit differentiation are outlined by Larson and Edwards as follows [15].

. This is where the process of implicit differentiation comes in. The steps of implicit differentiation are outlined by Larson and Edwards as follows [15].

- Differentiate both sides of the equation.

- Move all the terms with

to one side of the equation and all other terms to the other side.

to one side of the equation and all other terms to the other side. - Factor out

.

. - Solve for

.

.

Because we are solving for ![]() , it is assumed that

, it is assumed that ![]() is a function of

is a function of ![]() . That being said, it is easier to understand implicit differentiation if we let

. That being said, it is easier to understand implicit differentiation if we let ![]() before beginning these steps. Let’s now practice with a problem I completed for Calculus I from Larson and Edwards [15].

before beginning these steps. Let’s now practice with a problem I completed for Calculus I from Larson and Edwards [15].

Find

Solution

Let ![]() .

.

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \begin{align*} \frac{d}{dx}[x^3y^3-y]&=\frac{d}{dx}[x] &&\text{Differentiate w.r.t. $x$}\\ \frac{d}{dx}[x^3(f(x))^3-f(x)]&=\frac{d}{dx}[x] \\ x^3\frac{d}{dx}[(f(x))^3]+(f(x))^3\frac{d}{dx}[x^3]-\frac{d}{dx}[f(x)]&=\frac{d}{dx}[x] \\ x^3\left(3(f(x))^2 \frac{d}{dx}f(x)\right)+(f(x))^3(3x^2)-\frac{d}{dx}f(x)&=1 \\ x^3\left(3y^2 \frac{dy}{dx}\right)+y^3(3x^2)-\frac{dy}{dx}&=1 \\ 3x^3y^2\frac{dy}{dx}-\frac{dy}{dx}&=-3x^2y^3+1 &&\text{Move terms}\\ \frac{dy}{dx}(3x^3y^2-1)&=-3x^2y^3+1 &&\text{Factor out $\frac{dy}{dx}$}\\ \frac{dy}{dx}&=\frac{-3x^2y^3+1}{3x^3y^2-1} &&\text{Solve for $\frac{dy}{dx}$}\\ \end{align*}](https://iu.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/quicklatex/quicklatex.com-97f4f1cb3ecb16b8c2931ef4eab2fa4f_l3.png)

Therefore, the derivative of ![]() with respect to

with respect to ![]() where

where ![]() is

is

![]()

This means that if we could solve ![]() for

for ![]() , we would have that

, we would have that ![]() is a function of

is a function of ![]() ,

, ![]() , and the slope of

, and the slope of ![]() at

at ![]() would be

would be

![]()

We are now ready to begin discussing integrals which are like the other side of the derivative coin and are even sometimes referred to as antiderivatives.