3 Integrals

The integral of a function ![]() is usually thought of as the area between the graph of

is usually thought of as the area between the graph of ![]() and the

and the ![]() -axis. Although this is not a false idea, this description is only a piece of a much larger puzzle. It fails to unlock the true potential of integrals and prohibits a deeper understanding of what integrals are.

-axis. Although this is not a false idea, this description is only a piece of a much larger puzzle. It fails to unlock the true potential of integrals and prohibits a deeper understanding of what integrals are.

Integrals are, in essence, multiplication [5].

When we multiply, we are using repeated addition with numbers that remain fixed. For example, ![]() is adding 30 fours together (

is adding 30 fours together (![]() ). But what happens if the four is changing? What if we had this:

). But what happens if the four is changing? What if we had this:

![]()

Here is where integration comes in.

Azad uses the example of ![]() [5]. In real life, the speed will mostly likely be changing and will be different at different points in time. So, the equation would look like this:

[5]. In real life, the speed will mostly likely be changing and will be different at different points in time. So, the equation would look like this:

![]()

where ![]() is the speed at time

is the speed at time ![]() . First, the integral breaks the total time into many tiny intervals. Then, the speed at time

. First, the integral breaks the total time into many tiny intervals. Then, the speed at time ![]() , where

, where ![]() is the beginning of the interval, is multiplied by the length of the interval,

is the beginning of the interval, is multiplied by the length of the interval, ![]() , resulting in a tiny distance. This is done for each interval which results in a collection of tiny distances. Finally, the distances are added together to get the total distance [5]. All of this is done with this single equation:

, resulting in a tiny distance. This is done for each interval which results in a collection of tiny distances. Finally, the distances are added together to get the total distance [5]. All of this is done with this single equation:

![]()

Now let’s look at the formal definition provided by Larson and Edwards [15].

A function

In other words,

![]()

It is important to understand that the definition says ![]() is an antiderivative of

is an antiderivative of ![]() [15]. A function

[15]. A function ![]() can have many antiderivatives. The reasoning behind this goes back to the constant rule where

can have many antiderivatives. The reasoning behind this goes back to the constant rule where

![]()

for some real number ![]() . Consider

. Consider ![]() . Some antiderivatives include

. Some antiderivatives include

![]()

When we take the derivative of any of these, we end up with ![]() because the constant always becomes 0. For this reason, we say the antiderivative of

because the constant always becomes 0. For this reason, we say the antiderivative of ![]() is

is

![]()

where ![]() is a real number constant.

is a real number constant.

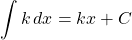

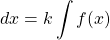

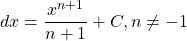

Just as we had derivative rules, we also have integral rules. A few of the basic ones are listed by Larson and Edwards as follows [15].

, where

, where  is a constant

is a constant

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \displaystyle\int [f(x)\pm g(x)]\, dx = \displaystyle\int f(x)\, dx \pm \displaystyle\int g(x)\, dx](https://iu.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/quicklatex/quicklatex.com-e19060d65f24cd756717bae5aa5fd304_l3.png)

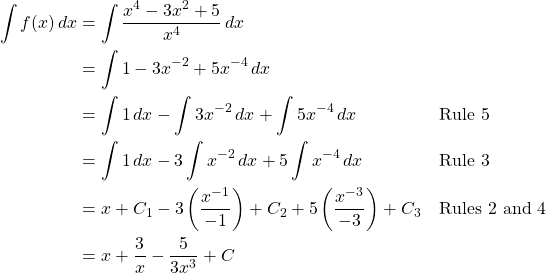

Let’s now work through an example to demonstrate some of these rules. This problem is one I completed for Calculus I and comes from Larson and Edwards [15].

Find the antiderivative of

Solution

Therefore, the antiderivative of ![]() is

is

![]()

where ![]() is a real number constant. That is, the derivative of

is a real number constant. That is, the derivative of

![]()

is ![]() .

.

An integral can come in many different forms, and often, we need to rewrite the integral so that it is in a form that can be integrated. One such strategy of rewriting integrals is integration by parts.

Integration by Parts

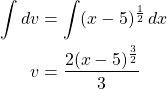

We have discussed how to integrate integrals using only the basic integration rules. But what happens when we have a function that cannot be integrated this way? Consider the function

![]()

We can write ![]() as the product of two functions,

as the product of two functions,

![]()

None of our basic integration rules tell us how to integrate products of functions so we need another method. This is where integration by parts comes in. Larson and Edwards give us the following theorem [15].

Theorem I.8

![]()

Proof.

Let ![]() and

and ![]() be functions of

be functions of ![]() with continuous derivatives.

with continuous derivatives.

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \begin{align*} \frac{d}{dx}[uv]&=u\frac{dv}{dx}+v\frac{du}{dx} &&\text{Product Rule}\\ \int\frac{d}{dx}[uv]\,dx&=\int u\frac{dv}{dx}\,dx+\int v\frac{du}{dx}\,dx &&\text{Integration Rule 5}\\ uv&=\int u\,dv+\int v\,du &&\text{dx's cancel}\\ \int u\,dv&=uv-\int v\,du &&\text{Rewrite}\\ \end{align*}](https://iu.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/quicklatex/quicklatex.com-1a71298a905d8ba46276755f23ffc916_l3.png)

The process is to break the function we are trying to integrate into two separate parts, ![]() and

and ![]() . Then, differentiate

. Then, differentiate ![]() to get

to get ![]() and integrate

and integrate ![]() to get

to get ![]() . Finally, subtract the integral of

. Finally, subtract the integral of ![]() from the product

from the product ![]() .

.

Let’s now revisit our function

![]()

and integrate it. This is a problem I completed for Calculus II that comes from Larson and Edwards [15].

Integrate

Solution

Let ![]() and

and ![]() It follows then that

It follows then that

So,

Therefore, the antiderivative of ![]() is

is

![]()

Keep in mind that there are many different methods and formulas for integration so integration by parts is not guaranteed to be the best method every time. But when faced with an integral that involves multiplying or dividing functions, it is a good method to try.

Another method that we have for rewriting integrals is trigonometric substitution.

Trigonometric Substitution

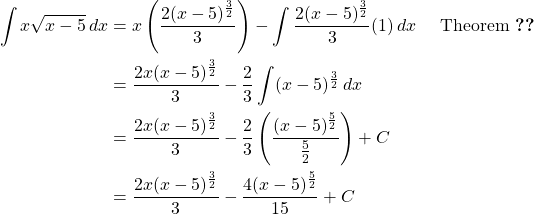

Trigonometric substitution is a very helpful method when integrating radicals. However, it is limited in that it only works with three general forms. The following summary of the forms and substitutions is from Larson and Edwards [15].

In order to understand why these substitutions work, we need a couple of Pythagorean identities [15]:

All that we need to do is substitute ![]() in and simplify using these Pythagorean identities. For example, the second form of trigonometric substitution looks like this:

in and simplify using these Pythagorean identities. For example, the second form of trigonometric substitution looks like this:

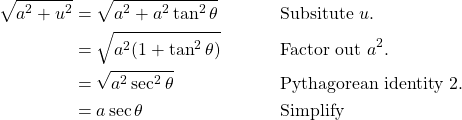

The other two follow a similar line of reasoning. Now, we will go through a problem I completed for Calculus II from Larson and Edwards [15].

Find ![]()

Solution

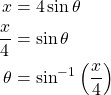

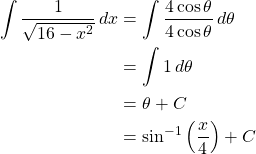

Let ![]() and

and ![]() . By trigonometric substitution,

. By trigonometric substitution,

Additionally,

Substituting everything in, we have

Therefore, the antiderivative of ![]() is

is

![]()

What we have been discussing so far is the indefinite integral. But there is another type of integral known as the definite integral.

Definite Integrals

The definite integral is denoted as

![]()

This simply means that we are integrating over a closed interval ![]() . We can evaluate such integrals using the following theorem given by Larson and Edwards [15].

. We can evaluate such integrals using the following theorem given by Larson and Edwards [15].

Theorem I.9 (The Fundamental Theorem of Calculus)

![]()

We are now going to look at some of the many real-world applications of derivatives and integrals. Additionally, we will work through a real-world problem involving derivatives and another involving integrals, which demonstrates the Fundamental Theorem of Calculus.